Assessing the Population Genetic Structure of the Endangered Cucumber Tree (Magnolia Acuminata) in Southwestern Ontario Using Nuclear and Chloroplast Genetic Markers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Department of Planning and Zoning

Department of Planning and Zoning Subject: Howard County Landscape Manual Updates: Recommended Street Tree List (Appendix B) and Recommended Plant List (Appendix C) - Effective July 1, 2010 To: DLD Review Staff Homebuilders Committee From: Kent Sheubrooks, Acting Chief Division of Land Development Date: July 1, 2010 Purpose: The purpose of this policy memorandum is to update the Recommended Plant Lists presently contained in the Landscape Manual. The plant lists were created for the first edition of the Manual in 1993 before information was available about invasive qualities of certain recommended plants contained in those lists (Norway Maple, Bradford Pear, etc.). Additionally, diseases and pests have made some other plants undesirable (Ash, Austrian Pine, etc.). The Howard County General Plan 2000 and subsequent environmental and community planning publications such as the Route 1 and Route 40 Manuals and the Green Neighborhood Design Guidelines have promoted the desirability of using native plants in landscape plantings. Therefore, this policy seeks to update the Recommended Plant Lists by identifying invasive plant species and disease or pest ridden plants for their removal and prohibition from further planting in Howard County and to add other available native plants which have desirable characteristics for street tree or general landscape use for inclusion on the Recommended Plant Lists. Please note that a comprehensive review of the street tree and landscape tree lists were conducted for the purpose of this update, however, only -

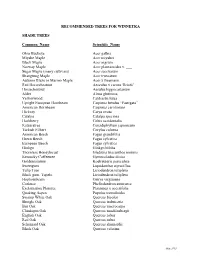

Recommended Trees for Winnetka

RECOMMENDED TREES FOR WINNETKA SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Ohio Buckeye Acer galbra Miyabe Maple Acer miyabei Black Maple Acer nigrum Norway Maple Acer plantanoides v. ___ Sugar Maple (many cultivars) Acer saccharum Shangtung Maple Acer truncatum Autumn Blaze or Marmo Maple Acer x freemanii Red Horsechestnut Aesculus x carnea 'Briotii' Horsechestnut Aesulus hippocastanum Alder Alnus glutinosa Yellowwood Caldrastis lutea Upright European Hornbeam Carpinus betulus “Fastigata” American Hornbeam Carpinus carolinians Hickory Carya ovata Catalpa Catalpa speciosa Hackberry Celtis occidentalis Katsuratree Cercidiphyllum japonicum Turkish Filbert Corylus colurna American Beech Fagus grandifolia Green Beech Fagus sylvatica European Beech Fagus sylvatica Ginkgo Ginkgo biloba Thornless Honeylocust Gleditsia triacanthos inermis Kentucky Coffeetree Gymnocladus dioica Goldenraintree Koelreuteria paniculata Sweetgum Liquidambar styraciflua Tulip Tree Liriodendron tulipfera Black gum, Tupelo Liriodendron tulipfera Hophornbeam Ostrya virginiana Corktree Phellodendron amurense Exclamation Plantree Plantanus x aceerifolia Quaking Aspen Populus tremuloides Swamp White Oak Quercus bicolor Shingle Oak Quercus imbricaria Bur Oak Quercus macrocarpa Chinkapin Oak Quercus muehlenbergii English Oak Quercus robur Red Oak Quercus rubra Schumard Oak Quercus shumardii Black Oak Quercus velutina May 2015 SHADE TREES Common_Name Scientific_Name Sassafras Sassafras albidum American Linden Tilia Americana Littleleaf Linden (many cultivars) Tilia cordata Silver -

Beyond the Fringe

Beyond the Fringe By Margaret Klein Wilson, Fairfax Master Gardener Intern The final flourish of native spring flowering trees belongs to fringe trees (Chionanthus virginicus). The measured parade of seasonal color — dogwoods and redbuds, flowering cherry and plum — is neatly capped by the fluttering grace of abundant white blossoms that engulf this small, often edge habitat tree beginning in mid-May. Encountering a fringe tree on a breezy spring day is to see masses of white corollas of petals casting their light perfume across the landscape. Is it any wonder Linnaeus named Yale ©2021 Copyright and noted this genus Chionanthus (chion = University snow; anthos = flower) as he compiled the photo: Genera Plantarum (1753)? Less poetically, fringe tree’s common names include Old Man’s Beard, Grancy graybeard, flowering ash and white fringe tree. Genus Chionanthus is a member of the Olive Family, the Olaceae, which includes 29 genera and over 600 species of trees and shrubs common in southeastern Asia and Australasia. Trees in this genus have uses both practical and ornamental: olive for food, ash for its lumber, and forsythia, gardenia and privets for sheer domestic beauty. In North America, ash trees in the genus Fraxinus, devilwood (Osmantus americanus) and Forestiera (swampprivet) are fringe tree’s near relatives. Only two species of fringe tree exist: C. virginicus in eastern North America and C. retusus, native to China. In his citation naming fringe tree the Virginia Native Plant Society 1997 Wildflower of the Year, C. F. Saachi explains this geographic disconnect: “This unusual biogeographic pattern, with different species within a genus … separated by several thousand miles, is a product of major geologic events including mountain building and the effects of glaciation. -

Indiana's Native Magnolias

FNR-238 Purdue University Forestry and Natural Resources Know your Trees Series Indiana’s Native Magnolias Sally S. Weeks, Dendrologist Department of Forestry and Natural Resources Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907 This publication is available in color at http://www.ces.purdue.edu/extmedia/fnr.htm Introduction When most Midwesterners think of a magnolia, images of the grand, evergreen southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) (Figure 1) usually come to mind. Even those familiar with magnolias tend to think of them as occurring only in the South, where a more moderate climate prevails. Seven species do indeed thrive, especially in the southern Appalachian Mountains. But how many Hoosiers know that there are two native species Figure 2. Cucumber magnolia when planted will grow well throughout Indiana. In Charles Deam’s Trees of Indiana, the author reports “it doubtless occurred in all or nearly all of the counties in southern Indiana south of a line drawn from Franklin to Knox counties.” It was mainly found as a scattered, woodland tree and considered very local. Today, it is known to occur in only three small native populations and is listed as State Endangered Figure 1. Southern magnolia by the Division of Nature Preserves within Indiana’s Department of Natural Resources. found in Indiana? Very few, I suspect. No native As the common name suggests, the immature magnolias occur further west than eastern Texas, fruits are green and resemble a cucumber so we “easterners” are uniquely blessed with the (Figure 3). Pioneers added the seeds to whisky presence of these beautiful flowering trees. to make bitters, a supposed remedy for many Indiana’s most “abundant” species, cucumber ailments. -

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L

THE Magnoliaceae Liriodendron L. Magnolia L. VEGETATIVE KEY TO SPECIES IN CULTIVATION Jan De Langhe (1 October 2014 - 28 May 2015) Vegetative identification key. Introduction: This key is based on vegetative characteristics, and therefore also of use when flowers and fruits are absent. - Use a 10× hand lens to evaluate stipular scars, buds and pubescence in general. - Look at the entire plant. Young specimens, shade, and strong shoots give an atypical view. - Beware of hybridisation, especially with plants raised from seed other than wild origin. Taxa treated in this key: see page 10. Questionable/frequently misapplied names: see page 10. Names referred to synonymy: see page 11. References: - JDL herbarium - living specimens, in various arboreta, botanic gardens and collections - literature: De Meyere, D. - (2001) - Enkele notities omtrent Liriodendron tulipifera, L. chinense en hun hybriden in BDB, p.23-40. Hunt, D. - (1998) - Magnolias and their allies, 304p. Bean, W.J. - (1981) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles VOL.2, p.641-675. - or online edition Clarke, D.L. - (1988) - Magnolia in Trees and Shrubs hardy in the British Isles supplement, p.318-332. Grimshaw, J. & Bayton, R. - (2009) - Magnolia in New Trees, p.473-506. RHS - (2014) - Magnolia in The Hillier Manual of Trees & Shrubs, p.206-215. Liu, Y.-H., Zeng, Q.-W., Zhou, R.-Z. & Xing, F.-W. - (2004) - Magnolias of China, 391p. Krüssmann, G. - (1977) - Magnolia in Handbuch der Laubgehölze, VOL.3, p.275-288. Meyer, F.G. - (1977) - Magnoliaceae in Flora of North America, VOL.3: online edition Rehder, A. - (1940) - Magnoliaceae in Manual of cultivated trees and shrubs hardy in North America, p.246-253. -

Phylogenomic Approach

Toward the ultimate phylogeny of Magnoliaceae: phylogenomic approach Sangtae Kim*1, Suhyeon Park1, and Jongsun Park2 1 Sungshin University, Korea 2 InfoBoss Co., Korea Mr. Carl Ferris Miller Founder of Chollipo Arboretum in Korea Chollipo Arboretum Famous for its magnolia collection 2020. Annual Meeting of Magnolia Society International Cholliop Arboretum in Korea. April 13th~22th, 2020 http://WWW.Chollipo.org Sungshin University, Seoul, Korea Dr. Hans Nooteboom Dr. Liu Yu-Hu Twenty-one years ago... in 1998 The 1st International Symposium on the Family Magnoliaceae, Gwangzhow Dr. Hiroshi Azuma Mr. Richard Figlar Dr. Hans Nooteboom Dr. Qing-wen Zeng Dr. Weibang Sun Handsome young boy Dr. Yong-kang Sima Dr. Yu-wu Law Presented ITS study on Magnoliaceae - never published Ten years ago... in 2009 Presented nine cp genome region study (9.2 kbp) on Magnoliaceae – published in 2013 2015 1st International Sympodium on Neotropical Magnoliaceae Gadalajara, 2019 3rd International Sympodium and Workshop on Neotropical Magnoliaceae Asterales Dipsacales Apiales Why magnolia study is Aquifoliales Campanulids (Euasterids II) Garryales Gentianales Laminales Solanales Lamiids important in botany? Ericales Asterids (Euasterids I) Cornales Sapindales Malvales Brassicales Malvids Fagales (Eurosids II) • As a member of early-diverging Cucurbitales Rosales Fabales Zygophyllales Celestrales Fabids (Eurosid I) angiosperms, reconstruction of the Oxalidales Malpighiales Vitales Geraniales Myrtales Rosids phylogeny of Magnoliaceae will Saxifragales Caryphyllales -

An Updated Classification of Magnoliaceae by H

An updated classification of Magnoliaceae by H. P. Nooteboom circumscissile, rarely indehiscent. Seeds 1 or more each fruiting carpel, Recently I have given a new large, in dehiscent carpets hanging classification of Magnoliaceae from the elongated spiral vessels of (Nooteboom, Blurnea 31. 1985:65- the funiculus, with arilloid testa, 121) which is an emendated version rarely, when fruit indehiscent of Dandy's classification in Treseder, adherent to the endocarp; endosperm Neil G. , Magnolias, 1978. Upon copious, oily; embryo minute. request I give here a condensed Characters of rare occurrence— version of my paper for the magnolia Leaves 2-10 lobed in Ldriodendron. votaries interested in the Flowers unisexual in ffrneria. classification of the family. Anthers extrorse in Liriodendron. MAGNOLIACEAE Fruit a loculicidal capsule in Pachylarnax, samaroid, winged, A. L. de Jussieu, Gen. Pl. :280 deciduous, and indehiscent in (1789) (Magnoliae). Lirlodendron. Trees or shrubs, glabrous or with Size and distribution —Seven an indumentum of single hairs. genera in temperate and tropical Leaves spirally arranged, simple, Southeast and East Asia and from entire or 2-10 lobed, penninerved North America southward through evergreen or deciduous; stipules the West Indies and Central America present, at first enclosing and to southern Brazil. protecting the innovations, later caducous and leaving an annular scar I. Subfamily MAGNOLIOIDEAE around the node. Flowers terminal or pseudo-axillary on a short shoot in Leaves entire or occasionally 2 the axils of the leaves, bisexual, lobed at the apex; stipules free from rarely unisexual, pedunculate. the petiole or adnate to it. Anthers Peduncle bearing 1 or more caducous introrse or latrorse. -

Effective Heat Transport During Miocene Cooling

EGU Journal Logos (RGB) Open Access Open Access Open Access Advances in Annales Nonlinear Processes Geosciences Geophysicae in Geophysics Open Access Open Access Natural Hazards Natural Hazards and Earth System and Earth System Sciences Sciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Chemistry Chemistry and Physics and Physics Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Measurement Measurement Techniques Techniques Discussions Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Open Access Biogeosciences Discuss., 10, 13563–13601, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/10/13563/2013/ Biogeosciences Biogeosciences BGD doi:10.5194/bgd-10-13563-2013 Discussions © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 10, 13563–13601, 2013 Open Access Open Access This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal BiogeosciencesClimate (BG). Climate Effective heat Please refer to the correspondingof finalthe Past paper in BG if available. of the Past Discussions transport during Miocene cooling Open Access Open Access Earth System Earth System T. Denk et al. Effective heat transportDynamics of Gulf StreamDynamics to Discussions subarctic North Atlantic during Miocene Title Page Open Access Geoscientific Geoscientific Open Access cooling: evidenceInstrumentation from “KöppenInstrumentation Abstract Introduction Methods and Methods and signatures” ofData fossil Systems plant assemblagesData Systems Conclusions References Discussions Open Access Open Access Tables Figures 1 1 2 2 Geoscientific T. Denk , G. W. Grimm , F.Geoscientific Grímsson , and R. Zetter Model Development 1 Model Development J I Swedish Museum of Natural History, Department of Palaeobotany, Box 50007,Discussions 10405 Stockholm, Sweden 2 J I Open Access University of Vienna, Department of Palaeontology,Open Access Althanstrasse 14, 1090 Vienna, Austria Hydrology and Hydrology and Back Close Received: 8 July 2013 – Accepted:Earth System 31 July 2013 – Published: 15 AugustEarth 2013 System Correspondence to: T. -

Pignut Hickory

Carya glabra (Mill.) Sweet Pignut Hickory Juglandaceae Walnut family Glendon W. Smalley Pignut hickory (Curya glabru) is a common but not -22” F) have been recorded within the range. The abundant species in the oak-hickory forest associa- growing season varies by latitude and elevation from tion in Eastern United States. Other common names 140 to 300 days. are pignut, sweet pignut, coast pignut hickory, Mean annual relative humidity ranges from 70 to smoothbark hickory, swamp hickory, and broom hick- 80 percent with small monthly differences; daytime ory. The pear-shaped nut ripens in September and relative humidity often falls below 50 percent while October and is an important part of the diet of many nighttime humidity approaches 100 percent. wild animals. The wood is used for a variety of Mean annual hours of sunshine range from 2,200 products, including fuel for home heating. to 3,000. Average January sunshine varies from 100 to 200 hours, and July sunshine from 260 to 340 Habitat hours. Mean daily solar radiation ranges from 12.57 to 18.86 million J mf (300 to 450 langleys). In Native Range January daily radiation varies from 6.28 to 12.57 million J m+ (150 to 300 langleys), and in July from The range of pignut hickory (fig. 1) covers nearly 20.95 to 23.04 million J ti (500 to 550 langleys). all of eastern United States (11). It extends from According to one classification of climate (20), the Massachusetts and the southwest corner of New range of pignut hickory south of the Ohio River, ex- Hampshire westward through southern Vermont and cept for a small area in Florida, is designated as extreme southern Ontario to central Lower Michigan humid, mesothermal. -

TREES of OHIO Field Guide DIVISION of WILDLIFE This Booklet Is Produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife As a Free Publication

TREES OF OHIO field guide DIVISION OF WILDLIFE This booklet is produced by the ODNR Division of Wildlife as a free publication. This booklet is not for resale. Any unauthorized reproduction is pro- hibited. All images within this booklet are copyrighted by the ODNR Division of Wildlife and its contributing artists and photographers. For additional INTRODUCTION information, please call 1-800-WILDLIFE (1-800-945-3543). Forests in Ohio are diverse, with 99 different tree spe- cies documented. This field guide covers 69 of the species you are most likely to encounter across the HOW TO USE THIS BOOKLET state. We hope that this guide will help you appre- ciate this incredible part of Ohio’s natural resources. Family name Common name Scientific name Trees are a magnificent living resource. They provide DECIDUOUS FAMILY BEECH shade, beauty, clean air and water, good soil, as well MERICAN BEECH A Fagus grandifolia as shelter and food for wildlife. They also provide us with products we use every day, from firewood, lum- ber, and paper, to food items such as walnuts and maple syrup. The forest products industry generates $26.3 billion in economic activity in Ohio; however, trees contribute to much more than our economic well-being. Known for its spreading canopy and distinctive smooth LEAF: Alternate and simple with coarse serrations on FRUIT OR SEED: Fruits are composed of an outer prickly bark, American beech is a slow-growing tree found their slightly undulating margins, 2-4 inches long. Fall husk that splits open in late summer and early autumn throughout the state. -

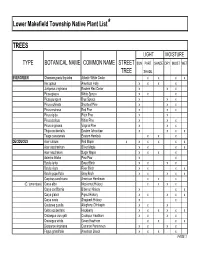

Native Plant List Trees.XLS

Lower Makefield Township Native Plant List* TREES LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE EVERGREEN Chamaecyparis thyoides Atlantic White Cedar x x x x IIex opaca American Holly x x x x Juniperus virginiana Eastern Red Cedar x x x Picea glauca White Spruce x x x Picea pungens Blue Spruce x x x Pinus echinata Shortleaf Pine x x x Pinus resinosa Red Pine x x x Pinus rigida Pitch Pine x x Pinus strobus White Pine x x x Pinus virginiana Virginia Pine x x x Thuja occidentalis Eastern Arborvitae x x x x Tsuga canadensis Eastern Hemlock xx x DECIDUOUS Acer rubrum Red Maple x x x x x x Acer saccharinum Silver Maple x x x x Acer saccharum Sugar Maple x x x x Asimina triloba Paw-Paw x x Betula lenta Sweet Birch x x x x Betula nigra River Birch x x x x Betula populifolia Gray Birch x x x x x Carpinus caroliniana American Hornbeam x x x (C. tomentosa) Carya alba Mockernut Hickory x x x x Carya cordiformis Bitternut Hickory x x x Carya glabra Pignut Hickory x x x x x Carya ovata Shagbark Hickory x x Castanea pumila Allegheny Chinkapin xx x Celtis occidentalis Hackberry x x x x x x Crataegus crus-galli Cockspur Hawthorn x x x x Crataegus viridis Green Hawthorn x x x x Diospyros virginiana Common Persimmon x x x x Fagus grandifolia American Beech x x x x PAGE 1 Exhibit 1 TREES (cont'd) LIGHT MOISTURE TYPE BOTANICAL NAME COMMON NAME STREET SUN PART SHADE DRY MOIST WET TREE SHADE DECIDUOUS (cont'd) Fraxinus americana White Ash x x x x Fraxinus pennsylvanica Green Ash x x x x x Gleditsia triacanthos v. -

Liriodendron Tulipifera Tuliptree1 Edward F

Fact Sheet ST-363 November 1993 Liriodendron tulipifera Tuliptree1 Edward F. Gilman and Dennis G. Watson2 INTRODUCTION Tuliptree grows 80 to 100 feet tall and maintains a fairly narrow oval crown, even as it grows older (Fig. 1). Trunks become massive in old age, becoming deeply furrowed with thick bark. The tree maintains a straight trunk and generally does not form double or multiple leaders. Older trees have several large- diameter major limbs in the top half of the crown. Tuliptree has a moderate to rapid (on good sites) growth rate at first but slows down with age. The soft wood reportedly is subject to storm damage but the trees held up remarkably well in the south during hurricane ‘Hugo’. It is probably stronger than given credit for. The largest trees in the east are in the Joyce Kilmer Forest in NC, some reaching more than 150 feet with seven-foot diameter trunks. The fall color is gold to yellow being more pronounced in the northern part of its range. The scented, tulip-like, greenish-yellow flowers appear in mid-spring but are not as ornamental as those of other flowering trees because they are far from view. GENERAL INFORMATION Scientific name: Liriodendron tulipifera Pronunciation: leer-ee-oh-DEN-drawn too-lih-PIFF-er-uh Common name(s): Tuliptree, Tulip-Poplar, Figure 1. Middle-aged Tuliptree. Yellow-Poplar Family: Magnoliaceae Availability: generally available in many areas within USDA hardiness zones: 5 through 9A (Fig. 2) its hardiness range Origin: native to North America Uses: shade tree; no proven urban tolerance 1.