Alternative Media and the Search for Queer Space

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Corporate Social Responsibility Culture Environment Entrepreneurship Community Employees Governance Building a Proud and Prosperous Québec Together

CONTRIBUTE CULTIVATE MOBILIZE 2020 CORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY CULTURE ENVIRONMENT ENTREPRENEURSHIP COMMUNITY EMPLOYEES GOVERNANCE BUILDING A PROUD AND PROSPEROUS QUÉBEC TOGETHER For more than 70 years, Quebecor has contributed to Québec’s economic, cultural and social vitality by joining forces with visionaries, creators, cultural workers and the next generation. Driven by our entrepreneurial spirit and strong philanthropic commitment, we make practical efforts on all fronts to support our culture, local entrepreneurs, our community, the environment and our employees. 400+ organizations supported across 1.46% Québec of Quebecor’s adjusted $28.56M EBITDA allocated to donations and in donations and sponsorships sponsorships in 2020 CONTRIBUTING TO THE VITALITY OF QUÉBEC’S ANDRE LYRA © CULTURAL INDUSTRIES FOR MORE THAN 70 YEARS CULTURE A CULTURE OF OUTREACH Québec culture is an integral part of our raison d’être. Through our business activities as well as our philanthropic initiatives, we support and promote talented Québec artists and creators, and we showcase the richness of our culture, our language, our history and our heritage. For over 70 years, we have been actively contributing to the vitality of Québec’s cultural industries. The crisis we and the rest of the world have been facing since the spring of 2020 has only intensified our commitment and our sense of responsibility to our culture Almost 50% of our donations Our efforts are making a difference for all artists, writers, composers, performers and and sponsorships went to cultural workers, and for everyone who wants to keep our culture vibrant and project it support the development onto the world stage. Our culture is our legacy. -

Spring Break in Paris

Spring Break in Paris Friday, March 21st to Sunday, March 30th, 2014 What you’ll do . Friday, March 21st – You’ll depart from Huntsville or Nashville International Airport bound for Europe. Usually there is a stop in one of the major cities of the east coast in order to catch your trans-Atlantic flight to Paris. Saturday, March 22nd – After flying through the night, you’ll land at Charles de Gaulle International Airport. After collecting your luggage and passing through customs, you’ll transfer into the city, usually by train. On evening one, there’s a short time for resting and refreshing at the hotel before heading out into the city for dinner and some sightseeing. You will ascend the 58-story Tour Montparnasse for the best views of Paris as the sun goes down and the lights come on in the city. Sunday, March 23rd– You’ll visit the Royal Palace of Versailles, just outside of Paris. In addition to touring the palace itself, you’ll want to visit the gardens, since Sunday is the only day the world-famous fountains are turned on. You will also have the opportunity to visit the Grand and Petit Trianon, small palaces built by the king on the grounds of Versailles in order to escape the pressures of palace life. Also not to be missed is the village-like hameau of Marie Antoinette. Later, you’ll head back to Paris for dinner and a visit to the Sacré-Coeur Basilica in Montmartre, the bohemian quarter of Paris. In Montmartre, you’ll also visit the Place du Tertre, where an artist will paint your portrait for a price. -

Highlights of a Fascinating City

PARIS HIGHLIGHTS OF A FASCINATING C ITY “Paris is always that monstrous marvel, that amazing assem- blage of activities, of schemes, of thoughts; the city of a hundred thousand tales, the head of the universe.” Balzac’s description is as apt today as it was when he penned it. The city has featured in many songs, it is the atmospheric setting for countless films and novels and the focal point of the French chanson, and for many it will always be the “city of love”. And often it’s love at first sight. Whether you’re sipping a café crème or a glass of wine in a street café in the lively Quartier Latin, taking in the breathtaking pano- ramic view across the city from Sacré-Coeur, enjoying a romantic boat trip on the Seine, taking a relaxed stroll through the Jardin du Luxembourg or appreciating great works of art in the muse- ums – few will be able to resist the charm of the French capital. THE PARIS BOOK invites you on a fascinating journey around the city, revealing its many different facets in superb colour photo- graphs and informative texts. Fold-out panoramic photographs present spectacular views of this metropolis, a major stronghold of culture, intellect and savoir-vivre that has always attracted many artists and scholars, adventurers and those with a zest for life. Page after page, readers will discover new views of the high- lights of the city, which Hemingway called “a moveable feast”. UK£ 20 / US$ 29,95 / € 24,95 ISBN 978-3-95504-264-6 THE PARIS BOOK THE PARIS BOOK 2 THE PARIS BOOK 3 THE PARIS BOOK 4 THE PARIS BOOK 5 THE PARIS BOOK 6 THE PARIS BOOK 7 THE PARIS BOOK 8 THE PARIS BOOK 9 ABOUT THIS BOOK Paris: the City of Light and Love. -

Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson 79 Rue Des Archives 75003 Paris

MARIE BOVOCRÉATION NOCTURNES EXPOSITIONS DE 25 FÉVRIERPHOTOGRAPHIES 17 MAI 2020 MARTINE FRANCKCOLLECTION FHCB FACE À FACE London / : Atalante-Paris — 2020 : Atalante-Paris Magnum Photos — Conception graphique Magnum Photos — Conception / FONDATION HENRI CARTIER-BRESSON 79 RUE DES ARCHIVES 75003 PARIS MARDI AU DIMANCHE DE 11H À 19H Paris mennour, the artist and kamel Courtesy Photos © Marie Bovo, © Martine Franck MARIE PRESS RELEASE BOVO NOCTURNES CREATION MARTINE FRANCK FACE À FACE COLLECTION FHCB FEBRUARY 25 - MAY 17 2020 PRESS CONTACT 79 rue des Archives – 75003 Paris Cécilia Enault 01 40 61 50 50 [email protected] henricartierbresson.org 79 rue des Archives - 75003 Paris 01 40 61 50 60 OPENING HOURS Tuesday to Sunday: 11am – 7pm PARTNERS ADMISSION Full rate 9 € / Concessions 5 € SOCIAL NETWORKS Front cover: © Marie Bovo, Courtesy the artist and kamel mennour, Paris/London © Martine Franck / Magnum Photos Graphic design: Atalante Paris - 2020 CONTENTS 5 FONDATION HCB 2020: A VERY PROLIFIC YEAR MARIE BOVO - NOCTURNES 6 EXHIBITION 7 BIOGRAPHY | PRESS IMAGES MARTINE FRANCK - FACE À FACE 9 EXHIBITION | BIOGRAPHY 10 PRESS IMAGES 11 2020 PROGRAMME AT 79 RUE DES ARCHIVES 12 PRESS IMAGES 13 SUPPORTERS OF THE FONDATION HCB FONDATION HCB – PRESS RELEASE – MARIE BOVO - MARTINE FRANCK - FEBRUARY / MAY 2020 4 FONDATION HCB 2020: A VERY PROLIFIC YEAR Two women photographers, two approaches, two eras, two practices, both with an unfussy sensitivity towards everyday life: Marie Bovo and Martine Franck are launching the 20s of photography here at the Fondation HCB, at 79 rue des Archives, with two exhibitions of unprecedented selections reflecting their enduring concerns. The Pearls from the Archives continue to offer visitors new perspectives on the talent and temperament of the young Henri Cartier-Bresson. -

Step Inside Hervé Van Der Straeten's Jewelbox Apartment on the Île

ANATOMY OF A HOME Step Inside Hervé Van der Straeten’s JewelBox Apartment on the Île SaintLouis The furniture designer and his fashionworld husband have decorated their Parisian piedàterre with an artfully arranged assemblage of covetable pieces both old and new. by Ian Phillips | photos by Stephan Julliard March 10, 2019 Furniture designer Hervé Van der Straeten (foreground) and his husband, former Roger Vivier artistic director Bruno Frisoni, recently moved into a one-bedroom apartment on Paris’s Île Saint-Louis, filling it with a mix of antique, vintage and contemporary pieces and artwork. Top: In the sitting room, a sofa and chairs by Van der Straeten flank a Pierre Charpin coffee table, and a Louis XV chair sits at a French Regency desk. hen furniture designer Hervé Van der Straeten and his husband, Bruno Frisoni, W decided to sell their loftlike apartment in Paris’s 12th arrondissement, they set out looking for something û di erent. “We wanted an experience we’d never had before,” says Van der Straeten. What they found was a 1,750squarefoot onebedroom apartment on the Île SaintLouis, right in the center of the city. The building in which it is situated has cultural as well as historic resonance: Constructed in the mid17th century, it was home to famed Barbizon School painter CharlesFrançois Daubigny in the mid 180os. The apartment appealed to Van der Straeten particularly because of its exquisite proportions and soaring, 14foothigh ceilings, plus its location directly on the banks of the Seine. -

Queer Periodicals Collection Timeline

Queer Periodicals Collection Timeline 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Series I 10 Percent 13th Moon Aché Act Up San Francisco Newsltr. Action Magazine Adversary After Dark Magazine Alive! Magazine Alyson Gay Men’s Book Catalog American Gay Atheist Newsletter American Gay Life Amethyst Among Friends Amsterdam Gayzette Another Voice Antinous Review Apollo A.R. Info Argus Art & Understanding Au Contraire Magazine Axios Azalea B-Max Bablionia Backspace Bad Attitude Bar Hopper’s Review Bay Area Lawyers… Bear Fax B & G Black and White Men Together Black Leather...In Color Black Out Blau Blueboy Magazine Body Positive Bohemian Bugle Books To Watch Out For… Bon Vivant 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 Bottom Line Brat Attack Bravo Bridges The Bugle Bugle Magazine Bulk Male California Knight Life Capitol Hill Catalyst The Challenge Charis Chiron Rising Chrysalis Newsletter CLAGS Newsletter Color Life! Columns Northwest Coming Together CRIR Mandate CTC Quarterly Data Boy Dateline David Magazine De Janet Del Otro Lado Deneuve A Different Beat Different Light Review Directions for Gay Men Draghead Drummer Magazine Dungeon Master Ecce Queer Echo Eidophnsikon El Cuerpo Positivo Entre Nous Epicene ERA Magazine Ero Spirit Esto Etcetera 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 -

Refiguring Masculinity in Haitian Literature of Dictatorship, 1968-2010

NORTHWESTERN UNIVERSITY Dictating Manhood: Refiguring Masculinity in Haitian Literature of Dictatorship, 1968-2010 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Field of French and Francophone Studies By Ara Chi Jung EVANSTON, ILLINOIS March 2018 2 Abstract Dictating Manhood: Refiguring Masculinity in Haitian Literature of Dictatorship, 1968- 2010 explores the literary representations of masculinity under dictatorship. Through the works of Marie Vieux Chauvet, René Depestre, Frankétienne, Georges Castera, Kettly Mars and Dany Laferrière, my dissertation examines the effects of dictatorship on Haitian masculinity and assesses whether extreme oppression can be generative of alternative formulations of masculinity, especially with regard to power. For nearly thirty years, from 1957 to 1986, François and Jean-Claude Duvalier imposed a brutal totalitarian dictatorship that privileged tactics of fear, violence, and terror. Through their instrumentalization of terror and violence, the Duvaliers created a new hegemonic masculinity articulated through the nodes of power and domination. Moreover, Duvalierism developed and promoted a masculine identity which fueled itself through the exclusion and subordination of alternative masculinities, reflecting the autophagic reflex of the dictatorial machine which consumes its own resources in order to power itself. My dissertation probes the structure of Duvalierist masculinity and argues that dictatorial literature not only contests dominant discourses on masculinity, but offers a healing space in which to process the trauma of the dictatorship. 3 Acknowledgements There is a Korean proverb that says, “백지장도 맞들면 낫다.” It is better to lift together, even if it is just a blank sheet of paper. It means that it is always better to do something with the help of other people, even something as simple as lifting a single sheet of paper. -

STOP AIDS Project Records, 1985-2011M1463

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8v125bx Online items available Guide to the STOP AIDS Project records, 1985-2011M1463 Laura Williams and Rebecca McNulty, October 2012 Department of Special Collections and University Archives October 2012; updated March 2019 Green Library 557 Escondido Mall Stanford 94305-6064 [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Guide to the STOP AIDS Project M1463 1 records, 1985-2011M1463 Language of Material: English Contributing Institution: Department of Special Collections and University Archives Title: STOP AIDS Project records, creator: STOP AIDS Project Identifier/Call Number: M1463 Physical Description: 373.25 Linear Feet(443 manuscript boxes; 136 record storage boxes; 9 flat boxes; 3 card boxes; 21 map folders and 10 rolls) Date (inclusive): 1985-2011 Special Collections and University Archives materials are stored offsite and must be paged 36-48 hours in advance. For more information on paging collections, see the department's website: http://library.stanford.edu/depts/spc/spc.html. Abstract: Founded in 1984 (non-profit status attained, 1985), the STOP AIDS Project is a community-based organization dedicated to the prevention of HIV transmission among gay, bisexual and transgender men in San Francisco. Throughout its history, the STOP AIDS Project has been overwhelmingly successful in meeting its goal of reducing HIV transmission rates within the San Francisco Gay community through innovative outreach and education programs. The STOP AIDS Project has also served as a model for community-based HIV/AIDS education and support, both across the nation and around the world. The STOP AIDS Project records are comprised of behavioral risk assessment surveys; social marketing campaign materials, including HIV/AIDS prevention posters and flyers; community outreach and workshop materials; volunteer training materials; correspondence; grant proposals; fund development materials; administrative records; photographs; audio and video recordings; and computer files. -

Dossier De Presse La Chambre Du Marais ENG.Cdr

LA CHAMBRE DU MARAIS PARIS PRESS KIT LA CHAMBRE DU MARAIS 87 rue des Archives, 75003 Paris Phone: +33 (0) 1.44.78.08.00 - [email protected] LA CHAMBRE DU MARAIS : THE COMFORT OF A COSY HOME, THE SERVICE OF A LUXURY HOTEL La Chambre du Marais is located in the heart of Paris. Only a few steps away from the Picasso Museum and the Pompidou Center; by staying in this four star hotel you will discover a unique and charming neighborhood, walk around the Place des Vosges, the tiny and picturesque streets from Paris’ historical heart, as well as the numerous art galleries and luxury boutiques. This beautiful 18th century building will plunge you in the district’s atmosphere as soon as you get there; you will just have to let yourself go with the ow for a visit of the real Paris! A perfect mix between a welcoming family house and the luxury hotel, you will be greeted casually and thus instantly made to feel at home. Nineteen tastefully decorated spacious rooms, partners carefully selected for their highlevel of quality and authenticity, an impeccable yet not too uptight: this is what La Chambre du Marais offers. The charm of this authentic place is enhanced by the work of a famous decorator, associated with talented artists and established designers. This new conception of the hotel industry combines the warm welcome of a cosy family house to the ne comfort of a luxury hotel. Welcome home! More information on www.lachambredumarais.com AN ELEGANT DECORATION SIGNED BY PHILIPPE JÉGOU Architect and interior designer Philippe Jégou was a longtime collaborator of Jacques Garcia, before creating his own agency Naos Décoration in 2008. -

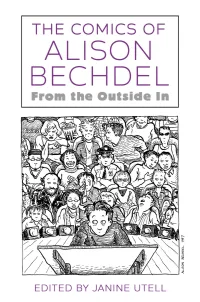

The Comics of Alison Bechdel from the Outside In

The Comics of Alison Bechdel From the Outside In Edited by Janine Utell University Press of Mississippi / Jackson CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS IX THE WORKS OF ALISON BECHDEL XI INTRODUCTION Serializing the Self in the Space between Life and Art JANINE UTELL XIII I. IN AND/OR OUT: QUEER THEORY, LESBIAN COMICS, AND THE MAINSTREAM THE HOSPITABLE AESTHETICS OF ALISON BECHDEL VANESSA LAUBER 3 “GIRLIE MAN, MANLY GIRL, IT’S ALL THE SAME TO ME” How Dykes to Watch Out For Shifted Gender and Comix ANNE N. THALHEIMER 22 DISSEMINATING QUEER THEORY Dykes to Watch Out For and the Transmission of Theoretical Thought KATHERINE PARKER-HAY 36 BECHDEL’S MEN AND MASCULINITY Gay Pedant and Lesbian Man JUDITH KEGAN GARDINER 52 VI CONTENTS MO VAN PELT Dykes to Watch Out For and Peanuts MICHELLE ANN ABATE 68 II. INTERIORS: FAMILY, SUBJECTIVITY, MEMORY DANCING WITH MEMORY IN FUN HOME ALISSA S. BOURBONNAIS 89 “IT BOTH IS AND ISN’T MY LIFE” Autobiography, Adaptation, and Emotion in Fun Home, the Musical LEAH ANDERST 105 GENERATIONAL TRAUMA AND THE CRISIS OF APRÈS-COUP IN ALISON BECHDEL’S GRAPHIC MEMOIRS NATALJA CHESTOPALOVA 119 THE EXPERIMENTAL INTERIORS OF ALISON BECHDEL’S ARE YOU MY MOTHER? YETTA HOWARD 135 INCHOATE KINSHIP Psychoanalytic Narrative and Queer Relationality in Are You My Mother? TYLER BRADWAY 148 III. PLACE, SPACE, AND COMMUNITY DECOLONIZING RURAL SPACE IN ALISON BECHDEL’S FUN HOME KATIE HOGAN 167 FUN HOME AND ARE YOU MY MOTHER? AS AUTOTOPOGRAPHY Queer Orientations and the Politics of Location KATHERINE KELP-STEBBINS 181 CONTENTS VII INSIDE THE ARCHIVES OF FUN HOME SUSAN R. -

My Father and I ��������������������������������������������������������������

My Father and I My Father and I The Marais and the Queerness of Community David Caron Cornell University Press ithaca and london Copyright © 2009 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2009 by Cornell University Press Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Caron, David (David Henri) My father and I : the Marais and the queerness of community / David Caron. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-4773-0 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Marais (Paris, France)—History. 2. Gay community—France—Paris—History. 3. Jewish neighborhoods—France—Paris—History. 4. Homosexuality—France—Paris— History. 5. Jews—France—Paris—History. 6. Gottlieb, Joseph, 1919–2004. 7. Caron, David (David Henri)—Family. I. Title. DC752.M37C37 2009 306.76'6092244361—dc22 2008043686 Cornell University Press strives to use environmentally responsible sup- pliers and materials to the fullest extent possible in the publishing of its books. Such materials include vegetable- based, low- VOC inks and acid- free papers that are recycled, totally chlorine- free, or partly composed of nonwood fibers. For further information, visit our website at www .cornellpress .cornell .edu . Cloth printing 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 In memory of Joseph Gottlieb, my father And for all my other friends Contents IOU ix Prologue. -

Whipping Girl

Table of Contents Title Page Dedication Introduction Trans Woman Manifesto PART 1 - Trans/Gender Theory Chapter 1 - Coming to Terms with Transgen- derism and Transsexuality Chapter 2 - Skirt Chasers: Why the Media Depicts the Trans Revolution in ... Trans Woman Archetypes in the Media The Fascination with “Feminization” The Media’s Transgender Gap Feminist Depictions of Trans Women Chapter 3 - Before and After: Class and Body Transformations 3/803 Chapter 4 - Boygasms and Girlgasms: A Frank Discussion About Hormones and ... Chapter 5 - Blind Spots: On Subconscious Sex and Gender Entitlement Chapter 6 - Intrinsic Inclinations: Explaining Gender and Sexual Diversity Reconciling Intrinsic Inclinations with Social Constructs Chapter 7 - Pathological Science: Debunking Sexological and Sociological Models ... Oppositional Sexism and Sex Reassignment Traditional Sexism and Effemimania Critiquing the Critics Moving Beyond Cissexist Models of Transsexuality Chapter 8 - Dismantling Cissexual Privilege Gendering Cissexual Assumption Cissexual Gender Entitlement The Myth of Cissexual Birth Privilege Trans-Facsimilation and Ungendering 4/803 Moving Beyond “Bio Boys” and “Gen- etic Girls” Third-Gendering and Third-Sexing Passing-Centrism Taking One’s Gender for Granted Distinguishing Between Transphobia and Cissexual Privilege Trans-Exclusion Trans-Objectification Trans-Mystification Trans-Interrogation Trans-Erasure Changing Gender Perception, Not Performance Chapter 9 - Ungendering in Art and Academia Capitalizing on Transsexuality and Intersexuality