Pometia Pinnata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evaluation of Some New Insecticide Mixtures for Management of Litchi

Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies 2019; 7(1): 1541-1546 E-ISSN: 2320-7078 P-ISSN: 2349-6800 Evaluation of some new insecticide mixtures for JEZS 2019; 7(1): 1541-1546 © 2019 JEZS management of litchi fruit borer Received: 26-11-2018 Accepted: 30-12-2018 SK Fashi Alam SK Fashi Alam, Biswajit Patra and Arunava Samanta Department of Agricultural Entomology, Bidhan Chandra Abstract Krishi Viswavidyalaya, Mohanpur, Nadia, West Bengal, Litchi fruit borer is a serious threat of litchi production causing significant economic losses. Insecticides India are the first choice to the farmers to manage this serious pest of litchi. Therefore, field experiments were conducted to evaluate some new mixture formulation of insecticides against litchi fruit borer during 2013 Biswajit Patra and 2014. The experiments were conducted at the Horticultural Farm of Bidhan Chandra Krishi Department of Agricultural Viswavidyalaya, Kalyani, Nadia, West Bengal, India in litchi orchard (cv. Bombai). Results of the Entomology, Uttar Banga Krishi experiments revealed that all the treatments were significantly superior over control. Chlorantraniliprole Viswavidyalaya, Pundibari, 9.3% +lambda cyhalothrin 4.6 % 150 ZC @ 35 g a.i./ha provided the best result both in terms of Cooch Behar, West Bengal, India minimum fruit infestation (12.12 %) and maximum yield (95.92 kg/plant in weight basis and 4316.5 fruit/plant in number basis) followed by the treatment chlorantraniliprole10% +thiamethoxam 20% 300 Arunava Samanta SC @150 g a.i./ha (13.10% mean fruit infestation). Amongst the various treatments, thiamethoxam Department of Agricultural 25WG was the least effective as this treatment recorded the highest fruit infestation (22.88 % mean fruit Entomology, Bidhan Chandra infestation) and thereby lowest yield (78.16 kg/plant in weight basis and 3517 fruit/ plant in number Krishi Viswavidyalaya, basis). -

Preferred Name

Cord 2006, 22 (1) Cocoa pod borer threatening the sustainable coconut-cocoa cropping system in Papua New Guinea S. P. Singh¹ and P. Rethinam¹ Abstract Cocoa pod borer Conopomorpha cramerella Snellen is an important pest of cocoa. Its recent invasion of cocoa in Papua New Guinea is threatening the sustainable coconut-cocoa cropping system. C. cramerella occurs only in South-East Asia and the western Pacific. It has been the single most important limiting factor to cocoa production in Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines. C. cramerella attacks cocoa, Theobroma cacao; rambutan, Nephelium lappaceum; cola, Cola acuminate; pulasan, Nephelium mutabile; kasai, Albizia retusa, nam-nam,Cynometra cauliflora; litchi (Litchi chinensis); longan (Dimocarpus longan) and taun, Pometia pinnata. The possible mode of its spread is through seed pods/fruits carried from previously infested regions. However, there is possibility of local adaptations of rambutan-feeders or nam-nam-feeders to cocoa. Females lay their eggs (50-100) on the surface of the unripe pods (more than five cm in length), which hatch in about 3-7 days and the emerging larvae tunnel their way to the center of the pod where they feed for about 14-18 days before chewing their way out of the pod to pupate. The pupal stage lasts 6- 8 days. The larval feeding results in pods that may ripen prematurely, with small, flat beans, often stuck together in a mass of dried mucilage. The beans from seriously infested pods are completely unusable and in heavy infestation over half the potential crop can be lost. Over four dozen species of natural enemies (parasitoids, predators, and entomopathogens) attack eggs, larvae, pupae and adults of C. -

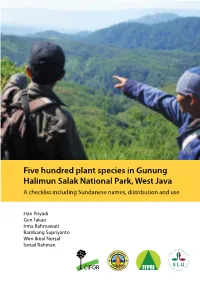

Five Hundred Plant Species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java a Checklist Including Sundanese Names, Distribution and Use

Five hundred plant species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java A checklist including Sundanese names, distribution and use Hari Priyadi Gen Takao Irma Rahmawati Bambang Supriyanto Wim Ikbal Nursal Ismail Rahman Five hundred plant species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java A checklist including Sundanese names, distribution and use Hari Priyadi Gen Takao Irma Rahmawati Bambang Supriyanto Wim Ikbal Nursal Ismail Rahman © 2010 Center for International Forestry Research. All rights reserved. Printed in Indonesia ISBN: 978-602-8693-22-6 Priyadi, H., Takao, G., Rahmawati, I., Supriyanto, B., Ikbal Nursal, W. and Rahman, I. 2010 Five hundred plant species in Gunung Halimun Salak National Park, West Java: a checklist including Sundanese names, distribution and use. CIFOR, Bogor, Indonesia. Photo credit: Hari Priyadi Layout: Rahadian Danil CIFOR Jl. CIFOR, Situ Gede Bogor Barat 16115 Indonesia T +62 (251) 8622-622 F +62 (251) 8622-100 E [email protected] www.cifor.cgiar.org Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) CIFOR advances human wellbeing, environmental conservation and equity by conducting research to inform policies and practices that affect forests in developing countries. CIFOR is one of 15 centres within the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). CIFOR’s headquarters are in Bogor, Indonesia. It also has offices in Asia, Africa and South America. | iii Contents Author biographies iv Background v How to use this guide vii Species checklist 1 Index of Sundanese names 159 Index of Latin names 166 References 179 iv | Author biographies Hari Priyadi is a research officer at CIFOR and a doctoral candidate funded by the Fonaso Erasmus Mundus programme of the European Union at Southern Swedish Forest Research Centre, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. -

View Newsletter

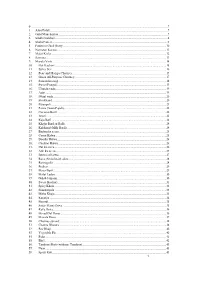

0. ..........................................................................................................................................................................................7 1. Aloo Palak.................................................................................................................................................................7 2. Gobi Manchurian.....................................................................................................................................................7 3. Sindhi Saibhaji..........................................................................................................................................................8 4. Shahi Paneer .............................................................................................................................................................9 5. Potato in Curd Gravy.............................................................................................................................................10 6. Navratan Korma .....................................................................................................................................................11 7. Malai Kofta.............................................................................................................................................................12 8. Samosa.....................................................................................................................................................................13 -

OK Industries

+91-8048761961 OK Industries https://www.indiamart.com/okinds/ We are one of the leading Manufacturer and Exporter of Non Stick Cookware, Stainless Steel Pressure Cooker, Hard Anodised Cookware. An ISO - 9001:2008 certified company, OK Industries has grown consistently over the last 59 years. About Us Established in 1956 by Shri Om Prakash Kapur, OK Industries is a leading Manufacturer and Exporter of Non Stick Cookware, Stainless Steel Pressure Cooker, Hard Anodised Cookware, Non Stick Gift Sets, Marble Coated Cookware, Stainless Steel Gift Set, Vacuum Bottle in the country. OK Industries is an ISO - 9001:2000 certified company and has grown consistently over the last 65 years. The company is also one of the few authorized licensee of the prestigious Teflon Coating by Du Pont Co. of USA. As of now, OK Industries offer a large variety of non-stick cookware, hard anodized cookware. Quality is of utmost importance to us and thus our products go through a series of stringent quality checks before they are ready to be used by the consumer. Our non-stick cookware bear ISI mark IS: 1660 Part-I and are manufactured from virgin aluminium metal. Our high quality products have been certified by the Bureau of Indian Standards. The company is equipped with latest machinery for production and quality control. We as a company encourage our distributors and dealers to perform better by offering them with attractive incentives. Getting repeat orders from overseas buyers has become a trend. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/okinds/profile.html -

Detection of Cocoa Pod Borer Infestation Using Sex Pheromone Trap and Its Control by Pod Wrapping

Jurnal Perlindungan Tanaman Indonesia, Vol. 21, No. 1, 2017: 30–37 DOI: 10.22146/jpti.22659 Research Article Detection of Cocoa Pod Borer Infestation Using Sex Pheromone Trap and its Control by Pod Wrapping Deteksi Serangan Penggerek Buah Kakao Menggunakan Perangkap Feromon Seks dan Pengendaliannya dengan Pembrongsongan Buah Dian Rahmawati1)*, Fransiscus Xaverius Wagiman1), Tri Harjaka1), & Nugroho Susetya Putra1) 1)Department of Crop Protection, Faculty of Agriculture, Universitas Gadjah Mada Jln. Flora 1, Bulaksumur, Sleman, Yogyakarta 55281 *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Received March, 1 2017; accepted May, 8 2017 ABSTRACT Cocoa pod borer (CPB), Conopomorpha cramerella Snellen (Lepidoptera: Gracillariidae) is a major pest of cocoa. Detection of the pest infestation using sex pheromone traps in the early growth and development of cocoa pods is important for an early warning system programme. In order to prevent the pest infestation the young pods were wrapped with plastic bags. A research to study the CPB incidence was conducted at cocoa plantations in Banjarharjo and Banjaroya villages, District of Kalibawang; Hargotirto and Hargowilis villages, District of Kokap; and Pagerharjo village, District of Samigaluh, Yogyakarta. The experiments design used RCBD with four treatments (sex pheromone trap, combination of sex pheromone trap and pod wrapping, pod wrapping, and control) and five replications. As many as 6 units/ha pheromone traps were installed with a distance of 40 m in between. Results showed that one month prior to the trap installation in the experimental plots there were ripen cocoa pods as many as 9-13%, which were mostly infested by CPB. During the time period of introducting research on August to Desember 2016 there was not rambutan fruits as the CPB host, hence the CPB resource was from infested cocoa pods. -

Contents to Our Readers

http://www-naweb.iaea.org/nafa/index.html http://www.fao.org/ag/portal/index_en.html No. 89, July 2017 Contents To Our Readers 1 Coordinated Research Projects 16 Other News 31 Staff 4 Developments at the Insect Pest Relevant Published Articles 37 Control Laboratory 19 Forthcoming Events 2017 5 Papers in Peer Reports 25 Reviewed Journals 39 Past Events 2016 6 Announcements 28 Other Publications 43 Technical Cooperation Field Projects 7 In Memoriam 30 To Our Readers Participants of the Third International Conference on Area-wide Management of Insect Pests: Integrating the Sterile Insect and Related Nuclear and Other Techniques, held from 22-26 May 2017 in Vienna, Austria. Over the past months staff of the Insect Pest Control sub- tries, six international organization, and nine exhibitors. As programme was very occupied with preparations for the in previous FAO/IAEA Area-wide Conferences, it covered Third FAO/IAEA International Conference on “Area-wide the area-wide approach in a very broad sense, including the Management of Insect Pests: Integrating the Sterile Insect development and integration of many non-SIT technolo- and Related Nuclear and Other Techniques”, which was gies. successfully held from 22-26 May 2017 at the Vienna In- The concept of area-wide integrated pest management ternational Centre, Vienna, Austria. The response and in- (AW-IPM), in which the total population of a pest in an terest of scientists and governments, as well as the private area is targeted, is central to the effective application of the sector and sponsors were once more very encouraging. The Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) and is increasingly being conference was attended by 360 delegates from 81 coun- considered for related genetic, biological and other pest Insect Pest Control Newsletter, No. -

An Electrophoretic Study of Natural Populations of the Cocoa Pod Borer, Canopomorpha Cramerella (Snellen) from Malaysia

Pertanika 12(1), 1-6 (1989) An Electrophoretic Study of Natural Populations of the Cocoa Pod Borer, Canopomorpha cramerella (Snellen) from Malaysia. RITA MUHAMAD, S.G. TAN, YY GAN, S. RITA, S. KANASAR and K. ASUAN. Departments of Plant Protection, Biology, and Biotechnology Universiti Pertanian Malaysia 43400 UPM Serdang, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia. Key words: Conopomorpha cramerella; cocoa pod borers; rambutan fruit borers; electromorphs; polymorphisms. ABSTRAK Pengorek buah koko dan Tawau, Sabah dan Sua Betong, Negeri Sembilan dan pengorek buah ramlmtan dan Serdang dan Puchong, Selangor dan Kuala Kangsar, Perak, Malaysia telah dianalisa secara elektroforesis dalam usaha untuk mendapatkan diagnosis elektromorf antar kedua biotip Conopomorpha cramerella. 30 enzim dan protein-protein umum telah dapat ditunjukkan pada zimogram-zimogram tetapi tidak ada satu pun yang boleh digunakan sebagai penanda diagnosis antara pengorek buah koko dengan pengorek buah rambutan. Frekwensi alil-alil untuk 8 enzim polimorfjuga dipaparkan. ABSTRACT Cocoa pod borers from Tawau, Sabah and Sua Betong, Negeri Sembilan and rambutan fruit borers from Serdang and Puchong, Selangor and Kuala Kangsar, Perak, Malaysia were subjected to electrophoretic analysis in an effort to find diagnostic electromorphs between these two biotypes ofConopomorpha cramerella. Thirty enzymes and general proteins were successfully demonstrated on zymograms but none of them could serve as diagnostic markers between cocoa pod borers and rambutanfruit borers. The allelicfrequencies for 8 polymorphic enzymes are presented. INTRODUCTION bromae cocoa L.) and that which attacks rambutan The cocoa pod borer, Conopomorpha cramerella (Nephelium lappaceum L.) fruits from the (Snellen) (Lepidoptera: Gracilariidae) is a Peninsula within a period of three months major cocoa pest in Sabah State, Malaysia but (November 1986 to January 1987) although until late 1986 it was only present as a minor unfortunately not from the same locality. -

I UG Food Preservation

Dr Ambedkar Government Arts College , Vyasarpadi, Chennai - 39 I B.Sc - Home Science - Nutrition , Food Service Management and Dietetics (UG) 2020-2021 Major paper FOOD PRESERVATION AND PROCESSING Unit - I Nature of harvested crop • The quality of harvested crop is dependant on the conditions of growth and on post harvest treatment. Storage condition of a crop is dependent on the function of composition, resistance to attacks by microorganisms, external conditions of temperature and gases in the environment • The most important characteristic of freshly harvested fruits and vegetables is that they are alive and respiring. • Ripening rendering the produce edible; as indicated by by taste. During ripening, starch is converted to sugar. When respiration declines, senescence (it ends at the death of the tissue of the fruit) develops in the last stage. • Maturity is indicated by skin colour, optical methods, shape, size, aroma, fruit opening, leaf changes and firmness. • Low temperature also disrupt the complex sequence of biochemical reactions taking place in plant tissue and cause a disorder known as chilling injury. • After harvesting decline in the rate of oxygen uptake and Carbon dioxide evolution to a low value is followed by a shark rise to a peak, terminating in pest- climacteric stage. The peak to minimum ratio tends to increase with temperature. this ratio varies among fruits. the slope of the rise varies with species maturity, temperature and the oxygen and Carbon dioxide of the storage chamber. Plant product storage Fresh fruits and vegetable maintain life processes during storage. As long as they are alive, they are able to resist the growth of spoilage organisms to some degree. -

To Travel the World For

SAVORED JOURNEYS PRESENTS 101 DISHES TO TRAVEL THE WORLD FOR EXPLORE THE CULTURE THROUGH THE FOOD savoredjourneys.com THE ULTIMATE LIST OF FOOD TO TRAVEL FOR By Laura Lynch of Savored Journeys Thank you for downloading 101 Dishes to Travel the World For and signing up to receive updates from Savored Journeys. I strongly believe there's no better way to discover a new culture than through food. That's why I put together this guide - so you can see for yourself all the amazing foods in the world that are absolutely worth traveling for! If you love food as much as we do, then you've come to the right place, because that's what Savored Journeys is all about. In the near future, we will be releasing an Around the World cookbook with all our favorite International recipes you can cook at home, along with wine pairings. In the meantime, we hope to pique your curiosity, perhaps encourage a bit of drooling and, above all, inspire you to travel for food. Visit us at http://www.savoredjourneys.com for more food and travel inspiration. WE ' RE GLAD YOU JOINED US! ABOUT SAVORED JOURNEYS From the tapas of Spain to the curries of Thailand, there's no food we're not willing to try, even if it involves intestines or insects. No matter where our adventures take us, food is a central part of our trip. Since eating involves all 5 senses, you’re in a heightened state when you interact with food, so intentionally experiencing food while you’re traveling will increased the intensity of the memories you build. -

Ethnomedicinal Plants Used for the Treatment of Cuts and Wounds by the Agusan Manobo of Sibagat, Agusan Del Sur, Philippines Mark Lloyd G

Ethnomedicinal plants used for the treatment of cuts and wounds by the Agusan Manobo of Sibagat, Agusan del Sur, Philippines Mark Lloyd G. Dapar, Ulrich Meve, Sigrid Liede- Schumann, Grecebio Jonathan D. Alejandro Research was significantly different (p < 0.05) when grouped according to occupation, educational level, civil status, gender, and age but not when grouped Abstract according to location (p = 0.234) and social position This study was conducted to investigate the (p = 0.580). ethnomedicinal plants used by the Agusan Manobo as potential drug leads for the treatment of cuts and Conclusion: The current study documents the wounds. Despite the prominence of the locality on medicinal plant knowledge of Agusan Manobo in the medicinal plant use, the area was previously ignored treatment of cuts and wounds. The traditional due to distance and security threat from the medicinal systems of Indigenous Cultural Communist Party of the Philippines - New People’s Communities/Indigenous Peoples (ICCs/IPs) are Army. Oral medicinal plant knowledge was sources of knowledge for bioprospecting. More documented. ethnobotanical studies should be encouraged before the traditional knowledge of indigenous people Methods: Ethnomedicinal survey was conducted vanishes. from October 2018 to February 2019 among 50 key informants through a semi-structured questionnaire; Correspondence open interviews and focus group discussions were conducted to gather information on medicinal plants Mark Lloyd G. Dapar1,3*, Ulrich Meve3, Sigrid used as a treatment for cuts -

Index Seminum 2018-2019

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI FEDERICO II ORTO BOTANICO INDEX SEMINUM 2018-2019 In copertina / Cover “La Terrazza Carolina del Real Orto Botanico” Dedicata alla Regina Maria Carolina Bonaparte da Gioacchino Murat, Re di Napoli dal 1808 al 1815 (Photo S. Gaudino, 2018) 2 UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI FEDERICO II ORTO BOTANICO INDEX SEMINUM 2018 - 2019 SPORAE ET SEMINA QUAE HORTUS BOTANICUS NEAPOLITANUS PRO MUTUA COMMUTATIONE OFFERT 3 UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI FEDERICO II ORTO BOTANICO ebgconsortiumindexseminum2018-2019 IPEN member ➢ CarpoSpermaTeca / Index-Seminum E- mail: [email protected] - Tel. +39/81/2533922 Via Foria, 223 - 80139 NAPOLI - ITALY http://www.ortobotanico.unina.it/OBN4/6_index/index.htm 4 Sommario / Contents Prefazione / Foreword 7 Dati geografici e climatici / Geographical and climatic data 9 Note / Notices 11 Mappa dell’Orto Botanico di Napoli / Botanical Garden map 13 Legenda dei codici e delle abbreviazioni / Key to signs and abbreviations 14 Index Seminum / Seed list: Felci / Ferns 15 Gimnosperme / Gymnosperms 18 Angiosperme / Angiosperms 21 Desiderata e condizioni di spedizione / Agreement and desiderata 55 Bibliografia e Ringraziamenti / Bibliography and Acknowledgements 57 5 INDEX SEMINUM UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI FEDERICO II ORTO BOTANICO Prof. PAOLO CAPUTO Horti Praefectus Dr. MANUELA DE MATTEIS TORTORA Seminum curator STEFANO GAUDINO Seminum collector 6 Prefazione / Foreword L'ORTO BOTANICO dell'Università ha lo scopo di introdurre, curare e conservare specie vegetali da diffondere e proteggere,