Big, Dans' Gang Rape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Interaction with the Public in Emergency Situations: Four Case Studies

MEDIA INTERACTION WITH THE PUBLIC IN EMERGENCY SITUATIONS: FOUR CASE STUDIES A Report Prepared under an Interagency Agreement by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress August 1999 Authors: LaVerle Berry Amanda Jones Terence Powers Project Manager: Andrea M. Savada Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540–4840 Tel: 202–707–3900 Fax: 202–707–3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage:http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/ PREFACE The following report provides an analysis of media coverage of four major emergency situations in the United States and the impact of that coverage on the public. The situations analyzed are the Three Mile Island nuclear accident (1979), the Los Angeles riots (1992), the World Trade Center bombing (1993), and the Oklahoma City bombing (1995). Each study consists of a chronology of events followed by a discussion of the interaction of the media and the public in that particular situation. Emphasis is upon the initial hours or days of each event. Print and television coverage was analyzed in each study; radio coverage was analyzed in one instance. The conclusion discusses several themes that emerge from a comparison of the role of the media in these emergencies. Sources consulted appear in the bibliography at the end of the report. i TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................................... i INTRODUCTION: THE MEDIA IN EMERGENCY SITUATIONS .................... iv THE THREE MILE ISLAND NUCLEAR ACCIDENT, 1979 ..........................1 Chronology of Events, March -

Immaculate Defamation: the Case of the Alton Telegraph

Texas A&M Law Review Volume 1 Issue 3 2014 Immaculate Defamation: The Case of the Alton Telegraph Alan M. Weinberger Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.tamu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan M. Weinberger, Immaculate Defamation: The Case of the Alton Telegraph, 1 Tex. A&M L. Rev. 583 (2014). Available at: https://doi.org/10.37419/LR.V1.I3.4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Texas A&M Law Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Texas A&M Law Review by an authorized editor of Texas A&M Law Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IMMACULATE DEFAMATION: THE CASE OF THE ALTON TELEGRAPH By: Alan M. Weinberger* ABSTRACT At the confluence of three major rivers, Madison County, Illinois, was also the intersection of the nation’s struggle for a free press and the right of access to appellate review in the historic case of the Alton Telegraph. The newspaper, which helps perpetuate the memory of Elijah Lovejoy, the first martyr to the cause of a free press, found itself on the losing side of the largest judgment for defamation in U.S. history as a result of a story that was never published in the paper—a case of immaculate defamation. Because it could not afford to post an appeal bond of that magnitude, one of the oldest family-owned newspapers in the country was forced to file for bankruptcy to protect its viability as a going concern. -

THE PRESS in CROWN HEIGHTS by Carol B. Conaway

FRAMING IDENTITY : THE PRESS IN CROWN HEIGHTS by Carol B. Conaway The Joan Shorenstein Center PRESS ■ POLI TICS Research Paper R-16 November 1996 ■ PUBLIC POLICY ■ Harvard University John F. Kennedy School of Government FRAMING IDENTITY: THE PRESS IN CROWN HEIGHTS Prologue 1 On the evening of August 19, 1991, the Grand Bystanders quickly formed a crowd around the Rebbe of the Chabad Lubavitch was returning car with the three Lubavitcher men, and several from his weekly visit to the cemetery. Each among them attempted to pull the car off of the week Rabbi Menachem Schneerson, leader of the Cato children and extricate them. Lifsh tried to worldwide community of Lubavitch Hasidic help, but he was attacked by the crowd, consist- Jews, visited the graves of his wife and his ing predominately of the Caribbean- and Afri- father-in-law, the former Grand Rebbe. The car can-Americans who lived on the street. One of he was in headed for the international headquar- the Mercury’s riders tried to call 911 on a ters of the Lubavitchers on Eastern Parkway in portable phone, but he said that the crowd Crown Heights, a neighborhood in the heart of attacked him before he could complete the call. Brooklyn, New York. As usual, the car carrying He was rescued by an unidentified bystander. the Rebbe was preceded by an unmarked car At 8:22 PM two police officers from the 71st from the 71st Precinct of the New York City Precinct were dispatched to the scene of the Police Department. The third and final car in accident. -

Surprise, Intelligence Failure, and Mass Casualty Terrorism

SURPRISE, INTELLIGENCE FAILURE, AND MASS CASUALTY TERRORISM by Thomas E. Copeland B.A. Political Science, Geneva College, 1991 M.P.I.A., University of Pittsburgh, 1992 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The Graduate School of Public and International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Pittsburgh 2006 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Thomas E. Copeland It was defended on April 12, 2006 and approved by Davis Bobrow, Ph.D. Donald Goldstein, Ph.D. Dennis Gormley Phil Williams, Ph.D. Dissertation Director ii © 2006 Thomas E. Copeland iii SURPRISE, INTELLIGENCE FAILURE, AND MASS CASUALTY TERRORISM Thomas E. Copeland, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2006 This study aims to evaluate whether surprise and intelligence failure leading to mass casualty terrorism are inevitable. It explores the extent to which four factors – failures of public policy leadership, analytical challenges, organizational obstacles, and the inherent problems of warning information – contribute to intelligence failure. This study applies existing theories of surprise and intelligence failure to case studies of five mass casualty terrorism incidents: World Trade Center 1993; Oklahoma City 1995; Khobar Towers 1996; East African Embassies 1998; and September 11, 2001. A structured, focused comparison of the cases is made using a set of thirteen probing questions based on the factors above. The study concludes that while all four factors were influential, failures of public policy leadership contributed directly to surprise. Psychological bias and poor threat assessments prohibited policy makers from anticipating or preventing attacks. Policy makers mistakenly continued to use a law enforcement approach to handling terrorism, and failed to provide adequate funding, guidance, and oversight of the intelligence community. -

CAMILLE BILLOPS B. 1933 Los Angeles, CA D. 2019 New York, NY

CAMILLE BILLOPS b. 1933 Los Angeles, CA d. 2019 New York, NY Education 1973 MFA, City College of New York 1960 BA, California State College Solo Exhibitions 2016 Still Raising Hell: The Art, Activism, and Archives of Camille Billops and James V. Hatch, Atlanta, GA 2012 Camille Billops: Prints & Posters, Leeway Foundation, Philadelphia, PA 2011 Films by Camille Billops, Hammer Museum at the University of California at Los Angeles 1997 Inside the Minstrel Mask, Noel Fine Art Acquisitions, Charlotte, North Carolina 1993 University of North Carolina at Charlotte 1990 Clark College, Atlanta University 1986 Calkins Gallery, Hofstra University, Hempsted, N.Y. Gallery at Quaker Corner, Plainfield, NJ 1984 Southeast Arkansas Arts & Science Center, Pine, Bluff 1993 University of North Carolina at Charlotte 1990 Clark College, Atlanta University 1986 Calkins Gallery, Hofstra University, Hempstead, N.Y. Gallery at Quaker Corner, Plainfield, NJ 1984 Southeast Arkansas Arts & Science Center, Pine, Bluff 1983 Pescadores Hsien Library, Making, Taiwan Chau Yea Gallery, Kaohsiung, Taiwan American Cultural Center, Taipei, Taiwan American Center, Karachi, Pakistan Otto Rene Castillo Center, New York 1981 The Bronx Museum of Art, Bronx, NY 1980 Harlem Book of the Dead Performance Piece, Buchhandlung Welt, Hamburg, West Germany 1977 Faculty Exhibition, Rutgers University, Newark, NJ 1976 Foto-Falle Gallery, Hamburg, West Germany 1974 Winston Salem North Carolina State University 1973 Ornette Coleman’s Artist House, SOHO, New York 1965 Galerie Akhenaton, Cairo, -

S/E(F% /02 R/E',A F- B/Uez

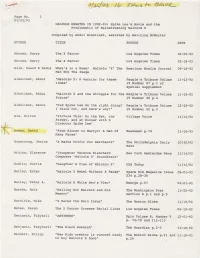

-: s/e(f% /02 r/e',A f- B/uez- Page No. 03/24/93 MALCOLMDEBATES IN 1992-93: Spike Lee's Movie and the Problematic of Mainstreaming Malcolm X Compiled by Abdul Alkalimat, aesisted by Mei-Ling McWorter AUTHOR TITLE SOURCE DATE Abrams, Garry The X Factor Los Angeles Times 02-06-92 Abrams, Garry The X Factor Los Angeles Times O2-L8-92 AIim, Dawud R Abdul What's in a Name? Malcolm "X" The American Muslim Journal 09-18-92 Man Not The Image Alkalimat, Abdul "Malcolm X: A warrior for these People's Tribune Volume tt-23-92 tlmeE" 19 Number 47 p.1 of special supplement Alkalimat, Abdul "Malcolm X and the struggle for the People's Tribune Volume Ll-16-92 future" 19 Number 46 p.4 AIkaIimat, Abdul "Did spike Lee do the right thing? People's Tribune Volume 12-28-92 I think not, and here's whyl" 19 Number 52 p.3 AIs, Hilton "Picture This: On the Set, the vilLage Voice tt/tolg2 Street, and at Dinner with X \*L-- Director Spike Lee" Ansen, David "From Sinner to Martyr: A Man Of Newsweek p.74 Lt-t5-92 4\ Many Faces" Armstrong, Jenice "X Marks Profit for Merchants" The Philadelphia Daily LO/30/92 News Atkins, Clarence "Trumpeter Terence Blanchard New York Amsterdam News l-L/14/92 Composes 'Malcolm X, Soundtrack" Austin, Curtis "Daughter's View of Malcolm X" USA Today tt / t6/e2 BaiIey, Ester "MaIcoIm X Rebel Without A pause" Spare Rib Magazine fssue 05-01-92 234 p.28-36 Bailey, Peter A. -

Martin Garbus Has a Diverse Practice That Consists of Individuals and Companies Involved in Politics, Media, Entertainment, and the Arts

[email protected] 347.589.8513| Fax 347.589.8535 10 East 40th Street| 18th Floor New York, NY 10016 PRACTICE FOCUS Martin Garbus has a diverse practice that consists of individuals and companies involved in politics, media, entertainment, and the arts. His courtroom skills have earned him a distinguished reputation as a trial lawyer. Mr. Garbus is experienced in every aspect of litigation and trial, from jury selection to cross-examination to summation. He has argued cases throughout the country involving constitutional, criminal, copyright, and intellectual property law. He has appeared before the United States Supreme Court, as well as trial and appellate courts throughout the United States. He has argued and written briefs that have been submitted to the United States Supreme Court; a number of which have resulted in changes in the law on a nationwide basis, including one described by Justice William Brennan as “probably the most important due process case in the Twentieth Century.” An international observer in foreign elections, he was selected by President Jimmy Carter to observe and report on the elections in Venezuela and Nicaragua. Mr. Garbus also participated in drafting several constitutions and foreign laws, including the Czechoslovak constitution. He also has been involved in prisoner exchange negotiations between governments. He is the author of six books and over 30 articles in The New York Times, The Washington Post and The Los Angeles Times. Mr. Garbus is featured in Shouting Fire, an award-winning documentary film about his life and career. He received the Fulbright Award for his work on International Human Rights in 2010. -

F Ja0pantingtinted Sllvr. Par O

perlodlco dlerlo qua lleeja a ta .urocele el mlsvnn din en nm pnhll Sllvr. par o. I cadn. stsndo flcl a mi farhs csde din Zltie. par IM lb dl aIn I paglna I coaHsrt le I TtflH nttlme nntlctsa dal die an esnsflnl Panting tinted Ld, par If Iba i ; Ja0SWTMWEST 33RD YEAR UMEST MMfHK NR ORCKiTIN I EL PASO, TEXAS, TUESDAY, AUGUST 19. 1913. TEN PAGES PRICE FIVE CENT Friends Show Loyalty With PRESIDENT HUERTA SEEKING TROUBLE Floral Token of Confidence. HUERTA REJECTS PLAN HUERTA AM) MNP E HIS ISSUED OPEN DEFIANCE HOI, II UON'FF.RF.XCE SUGGESTION BY LIND Bp rirllKfliWI'mi d Mexico OS?, :Sn a. m. , Aa. IS. Provisional Pmlrifni Hirer. iMmXt ia and John I tn.i ,.. .ni rep. af m TURNED DOWN IN MEXICO CITY OF UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT riaiaaqif or Wilson. 9 wajt'ey St roainrnrr at a late howr L Jhr ' tonight following the report thai - xi3 that President Haerta wotald give Use I n led Ma Ira until mid- - e Re- nlghl to recognise hi edtaiat- - s Statement Reiterated That Under No Demands That His Government be ' radon under throat of rtrrini all relation. The nai.aro of ttra Circumstances Will the United cognized by Washington Authorities, oonfermoa was not revealed, bat States H 1DM characterized an cordial. Recognize Huerta. President Wilson and Insisted on Reply Before Midnight. a-- I Disappointed. By the Associated Press. NOTHINO dy 18. UNTU)omintLATER TODAV Bp thr daaoetsfaa' Washington, August ' Washington. Aug. The Huerta can senators, with very few excep- 'i Bp Tlmrn Special rorreapoadsal litem! rejection nf the tion, have upheld the hands of Pit officials were by I si. -

Eleanor's Story: Growing up and Teaching in Iowa: One African American Woman's Experience Kay Ann Taylor Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2001 Eleanor's story: growing up and teaching in Iowa: one African American woman's experience Kay Ann Taylor Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the African American Studies Commons, Educational Sociology Commons, Oral History Commons, Other Education Commons, Other History Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social History Commons, United States History Commons, Women's History Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Taylor, Kay Ann, "Eleanor's story: growing up and teaching in Iowa: one African American woman's experience " (2001). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 681. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/681 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMl films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMl a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

The Graduate Student Advocate, Summer 1992, Vol. 3, No. 6

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works The Advocate Archives and Special Collections Summer 1992 The Graduate Student Advocate, Summer 1992, Vol. 3, No. 6 How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_advocate/44 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Graduate -Student b\.locatt Volume 3 City University of New York SUMMER1992 Number6 $3.17 Million in Graduate School Cuts to Financial Aid and Faculty Hiring The.LA riots or intifada are the return of the oppressed on the US social landscape. US cities, long starved by disinvestment, withdrawal of social spending and the The Graduate Center is implementing cuts of $3.17 million In an 8-3 vote, the Trustees of the City University of New desiccation of social services, have been propelled into for next year, which will impact student services, financial York approved a tuition hike of $600 per year for first-year the collective consciousness of TV networks. The LA aid, faculty and staff. The amount of financial aid avail-. and transfer students at the senior colleges. Returning suburbs were forced to recognize their doppleganger in able to students will continue to decline. Vacant faculty CUNY undergraduates and all students at the junior col- South Central, while the flight from New York on May I st and staff positions will not be filled. Administrative of- leges will pay $350 more per year in tuition. -

The New York News Media and the Central Park Rape

THE NEW YORK NEWS MEDIA AND THE CENTRAL PARK RAPE Linda S. Lichter S. Robert Lichter Daniel Amundson 13 • V 1^1 THE AMERICAN JEWISH COMMITTEE, Institute of Human Relations, 165 East 56 Street, New York, NY 10022 2746 CENTER FOR MEDIA AND PUBLIC AFFAIRS «ft / ^\ A^L 2101 L Street. N.W. • Suite 505 • Washington, D.C. 20037 V. \i• / C (7 ^7 Linda S. Lichter, Ph.D., is a sociologist specializing in public opinion and political sociology. S. Robert Lichter, Ph.D., is a political scientist specializing in mass media and research methods. They are co-directors of the Center for Media and Public Affairs in Washington, D.C. Daniel Amundson, a graduate student in sociology at George Washington University, is research director at the Center. Copyright © 1989 The American Jewish Committee All rights reserved Executive Summary The rape of a jogger in New York's Central Park this spring touched off a controversy over the media's reporting of interracial crimes. Charges of sensationalism and racism were raised and debated. We have analyzed the topics, themes, and language of local media coverage for two weeks after the attack (April 20 to May 4). Using the method of content analysis, we examined 406 news items in New York's four daily newspapers, the weekly Amsterdam News, and evening newscasts of the city's six television stations. Although the racial element was conspicuous in this story, the content analysis found no evidence that media coverage played on racial fears or hatreds. On the contrary, the question of race was repeatedly raised in order to deny its relevance to the crime, to warn against reviving racial tension, and to call for a healing process to defuse racial animosity. -

Las Vegas Optic, 08-24-1909 the Optic Publishing Co

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Las Vegas Daily Optic, 1896-1907 New Mexico Historical Newspapers 8-24-1909 Las Vegas Optic, 08-24-1909 The Optic Publishing Co. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lvdo_news Recommended Citation The Optic Publishing Co.. "Las Vegas Optic, 08-24-1909." (1909). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/lvdo_news/2752 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the New Mexico Historical Newspapers at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Las Vegas Daily Optic, 1896-1907 by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i h.. 4 3 O. c WEATHER WE FEINT FORECAST the i;ev;s if- ' - If You Read In Th Showers Tonight ' I , "V V J U-- It 1 1 J v Sr LJ Li U 4 Optic, It's So. or Wednesday ij Vr VOL. XXX. NO. 252. EAST LAS VEGAS, NEW MEXICO, TUESDAY. AUGUST 24, 1909. FIVE O'CLOCK EDITION. has asserted she could raise the deal Cluxton,' accompanied by Mr. Ilfeld. Her friends have feared that she The sixth number was a whistling TULLE might kill her children, as she had HUNDREDS olo by Miss Cora Fettijobn, which BAKU SIRS. if die caught the ear of those attending. Af told people that they should she could resurrect them from their The performance ended with a second graves. moving picture. t Finally her condition became so It was announced tbis niornlufc 'hat ATTEMPTED acute that application was made for WHEN EXCURSION after deducting the expenses of the SAYS HE'S her commitment to the asylum, and entertainment, there would be left after an examination yesterday aftc-r- the sum of $36 as Captain VVillson's noon, the court ordered her so con- share.