Venezuela: How Long Can This Go On? | Americas Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FINAL DRAFT State and Power After Neoliberalism in Bolivarian

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title State and Power after Neoliberalism in Bolivarian Venezuela Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/86g3m849 Author Kingsbury, Donald V. Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ STATE AND POWER AFTER NEOLIBERALISM IN BOLIVARIAN VENEZUELA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICS with emphases in LATIN AMERICAN AND LATINO STUDIES and HISTORY OF CONSCIOUSNESS by Donald V. Kingsbury June 2012 The Dissertation of Donald V. Kingsbury is approved: ____________________________________ Professor Megan Thomas, Chair ____________________________________ Professor Juan Poblete ____________________________________ Professor Gopal Balakrishnan ____________________________________ Professor Michael Urban _________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Donald V. Kingsbury 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures iv Abstract v Acknowledgments vi I. Introduction 1 II. Between Multitude and Pueblo 53 III. The Problem with Populism 120 IV. The Power of the Many 169 V. The Discursive Production of a ‘Revolution’ 219 VI. ‘…after Neoliberalism?’ 277 VII. Conclusion 342 VIII. Bibliography 362 ! """! LIST OF FIGURES Figure 0.1 Seven Presidential elections and four referenda during the Bolivarian Revolution, 1998-2010. 18 Figure 1.1 "Every 11th has its 13th: The Pueblo is still on the street, but today it’s on the road to socialism!" 102 Figure 3.1 “Here comes the People’s Capitalism” 201 Figure 4.1: Advertisement of ‘Mi Negra’ Program 221 Figure 4.2 ¡Rumbo al Socialismo Bolivariano! 261 Figure 4.3. -

Community Security in Caracas: the Collective Action of Foundation Alexis Vive

COMMUNITY SECURITY IN CARACAS: THE COLLECTIVE ACTION OF FOUNDATION ALEXIS VIVE A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Latin American Studies By Jonathan Weinstock, B.A. Washington, DC August 25, 2015 Copyright 2015 by Jonathan Weinstock All Rights Reserved ii COMMUNITY SECURITY IN CARACAS: THE COLLECTIVE ACTION OF FOUNDATION ALEXIS VIVE Jonathan Weinstock, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Marc W Chernick, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This thesis is divided into two arguments. The first part is an argument for community security: a community-based vision of human security, which conflates development and personal security. Social movements then animate community security, addressing local problems and creating endogenous solutions. Arturo Escobar’s work on post-development theory and Raúl Zibechi’s new social movements as territories in resistance best explains this phenomenon. At the community level, I utilize Stephen Schneider’s work on community crime prevention and organic mobilization as complex and difficult to maintain. With this lens, I establish an analytical framework for community security movements based on the themes of identity, praxis, constituency and autonomy. Examinations on gender relations, networks, violence and production are also weaved into the analysis. The second part is an argument that a Caracas (Venezuela) based group is a community security movement and that this analytical framework is best fitted for understanding them. Though Caracas is among the most insecure and politically turbulent cities in Latin America, small pockets of peace exist in working class neighborhoods. -

Venezuela: Political Reform Or Regime Demise?

VENEZUELA: POLITICAL REFORM OR REGIME DEMISE? Latin America Report N°27 – 23 July 2008 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. 2007: SEEKING CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM AND REGIME CONSOLIDATION........................................................................................................... 2 A. ACCELERATING THE REVOLUTION ................................................................................................2 B. THE CONSTITUTIONAL REFORM....................................................................................................3 C. WANING SUPPORT ........................................................................................................................4 1. Political context ......................................................................................................................4 2. Socio-economic and public security problems.......................................................................7 D. INTERNATIONAL CONTEXT ...........................................................................................................9 E. THE DECEMBER 2007 REFERENDUM...........................................................................................11 III. 2008: THE BEGINNING OF THE END FOR CHAVEZ?......................................... 13 A. IS POLITICAL REFORM STILL POSSIBLE? .....................................................................................13 -

Venezuela: Accelerating the Bolivarian Revolution

Update Briefing Latin America Briefing N°22 Bogotá/Brussels, 5 November 2009 Venezuela: Accelerating the Bolivarian Revolution I. OVERVIEW remaining popularity with certain sectors of society are likely to be sufficient to allow him and his party to pre- serve their control of the National Assembly. President Hugo Chávez’s victory in the 15 February 2009 referendum, permitting indefinite re-election of all elected officials, marked an acceleration of his “Boli- II. REVERSING THE REGIME’S FORTUNE varian revolution” and “socialism of the 21st century”. Chávez has since moved further away from the 1999 In a close December 2007 referendum (51 per cent to constitution, and his government has progressively aban- 49 per cent), Chávez was denied permission to reform doned core liberal democracy principles guaranteed the constitution he himself had promulgated in 1999. This under the Inter-American Democratic Charter and the was the first electoral setback since he took office in 1998 American Convention on Human Rights. The executive and a clear message from both the pro- and anti-Chávez has increased its power and provoked unrest internally camps that some of the more radical initiatives in his by further politicising the armed forces and the oil sector, reform package were unwelcome.1 In November 2008, as well as exercising mounting influence over the elec- Chávez and his recently created PSUV party won seven- toral authorities, the legislative organs, the judiciary and teen of 22 states and 263 of 326 municipalities in the other state entities. At the same time, Chávez’s attempts municipal and regional elections, but they also suffered to play a political role in other states in the region are losses and forfeited former strongholds.2 The biggest producing discomfort abroad. -

Violence and Politics in Venezuela

VIOLENCE AND POLITICS IN VENEZUELA Latin America Report N°38 – 17 August 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. ROOTS OF VIOLENCE .................................................................................................. 2 III. THE RISE IN VIOLENCE UNDER CHÁVEZ ............................................................. 3 A. GROWING CRIMINAL VIOLENCE................................................................................................... 3 B. INTERNATIONAL ORGANISED CRIME ............................................................................................ 6 C. POLITICAL VIOLENCE ................................................................................................................ 10 IV. ARMED GROUPS: COMBINING CRIME, VIOLENCE AND POLITICS............ 12 A. COLOMBIAN GUERRILLAS .......................................................................................................... 12 B. BOLIVARIAN LIBERATION FORCES ............................................................................................. 16 C. THE URBAN COLECTIVOS ........................................................................................................... 17 V. INSTITUTIONAL DECAY ............................................................................................ 19 A. -

FINAL DRAFT State and Power After Neoliberalism in Bolivarian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ STATE AND POWER AFTER NEOLIBERALISM IN BOLIVARIAN VENEZUELA A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in POLITICS with emphases in LATIN AMERICAN AND LATINO STUDIES and HISTORY OF CONSCIOUSNESS by Donald V. Kingsbury June 2012 The Dissertation of Donald V. Kingsbury is approved: ____________________________________ Professor Megan Thomas, Chair ____________________________________ Professor Juan Poblete ____________________________________ Professor Gopal Balakrishnan ____________________________________ Professor Michael Urban _________________________ Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright © by Donald V. Kingsbury 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Figures iv Abstract v Acknowledgments vi I. Introduction 1 II. Between Multitude and Pueblo 53 III. The Problem with Populism 120 IV. The Power of the Many 169 V. The Discursive Production of a ‘Revolution’ 219 VI. ‘…after Neoliberalism?’ 277 VII. Conclusion 342 VIII. Bibliography 362 ! """! LIST OF FIGURES Figure 0.1 Seven Presidential elections and four referenda during the Bolivarian Revolution, 1998-2010. 18 Figure 1.1 "Every 11th has its 13th: The Pueblo is still on the street, but today it’s on the road to socialism!" 102 Figure 3.1 “Here comes the People’s Capitalism” 201 Figure 4.1: Advertisement of ‘Mi Negra’ Program 221 Figure 4.2 ¡Rumbo al Socialismo Bolivariano! 261 Figure 4.3. Youth and Student campaign for Bolivarian Socialism. 266 Figure 4.4 Juan Dávila El Libertador Simón Bolívar 269 Figure 5.1 Looking Back 297 ! "#! ABSTRACT State and Power after Neoliberalism in Bolivarian Venezuela Donald V. Kingsbury State and Power after Neoliberalism in Bolivarian Venezuela examines the limits and possibilities of collective subject formation in the context of social transformation. -

Conceptualizing the Bolivarian Revolution: a Critical Discourse Analysis of Chávez's Rhetorical Framing in Aló Presidente A

Conceptualizing the Bolivarian Revolution: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Chávez’s Rhetorical Framing in Aló Presidente A thesis presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Science Ayleen A. Cabas-Mijares August 2016 © 2016 Ayleen A. Cabas-Mijares. All Rights Reserved. This thesis titled Conceptualizing the Bolivarian Revolution: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Chávez’s Rhetorical Framing in Aló Presidente by AYLEEN A. CABAS-MIJARES has been approved for the E. W. Scripps School of Journalism and the Scripps College of Communication by Yusuf Kalyango Jr. Associate Professor of Journalism Scott Titsworth Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT CABAS-MIJARES, AYLEEN A., M.S., August 2016, Journalism Conceptualizing the Bolivarian Revolution: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Chávez’s Rhetorical Framing in Aló Presidente Director of Thesis: Yusuf Kalyango Jr. This critical discourse analysis of the late Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez’s time in office explores the rhetorical frames he employed to characterize the Bolivarian Revolution in his weekly television and radio show, Aló Presidente. After iterative readings of the transcripts of 40 Aló Presidente episodes that spanned almost the entire Chávez presidency, the study shows that the president employed historical, socioeconomic and religious rhetorical frames to define and promote the Bolivarian Revolution as a desirable governance manifesto. Chávez’s rhetorical framing presented the revolution as the only bastion of patriotism, ethical and Christian values in Venezuela, which resulted in the vilification of dissent and the legitimation of political discrimination. In summary, the findings indicate that President Chávez’s discursive practices and overall media strategy and dominance of the media landscape set the stage for the violation of Venezuelans’ right to access diverse information as well as their freedom of expression. -

Download Book

GRASSROOTS POLITICS AND OIL CULTURE IN VENEZUELA THE REVOLUTIONARY PETRO-STATE Iselin Åsedotter Strønen Grassroots Politics and Oil Culture in Venezuela Iselin Åsedotter Strønen Grassroots Politics and Oil Culture in Venezuela The Revolutionary Petro-State Iselin Åsedotter Strønen University of Bergen Bergen, Hordaland Fylke, Norway Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) Bergen, Hordaland Fylke, Norway ISBN 978-3-319-59506-1 ISBN 978-3-319-59507-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-59507-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2017945573 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2017. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. -

Venezuela: How Long Can This Go On? | Americas Quarterly

Venezuela: How Long Can This Go On? | Americas Quarterly http://www.americasquarterly.org/content/venezuela-how-long-... ENTER ZIP CODE SEARCH OUR SITE Subscribe About Blog News Contact Advertise Archive Partners From issue: Higher Education and Competitiveness (Summer 2014) Venezuela: How Long Can This Go On? BY Boris Muñoz 1 of 13 3/8/15, 12:39 PM Venezuela: How Long Can This Go On? | Americas Quarterly http://www.americasquarterly.org/content/venezuela-how-long-... Will the country make it to the next elections? On April 10, Venezuelans stayed up past midnight to watch an event on TV that just a few weeks prior would have seemed incredible, almost miraculous: after three months of intense protests, headed by students in alliance with the most combative sectors of the opposition calling for President Nicolás Maduro’s departure, the government and the opposition, thanks to mediation from the Unión de Naciones Suramericanas (Union of South American Nations—UNASUR), sat down to negotiate. In fact, according to Henry Ramos Allup, a veteran National Assembly member from the opposition party Acción Democrática (Democratic Action—AD), it was the first time in over a decade that the main actors in the political conflict in Venezuela debated as civilized people. An extraordinary moment in a country whose unicameral national legislature has become at times a boxing ring. Public opinion surveys show that between 70 and 84 percent of Venezuelans support the negotiations. But one month after the start of the talks, any hope that they would resolve the crisis evaporated. The talks broke down over the government’s brutal breakup of protester camps in Caracas by the National Guard in the middle of the night while the occupants were sleeping, and over the massive arbitrary arrests—more than 300 in a week—of students and young people across the country. -

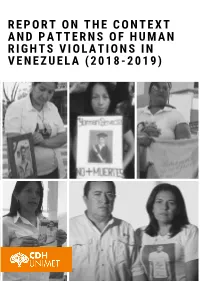

Report on the Context and Patterns of Human Rights Violations in Venezuela

REPORT O N THE C ONTEX T A ND PA TTERNS OF H U MA N RI GHTS V I OLA TI ONS I N VENEZU EL A (2018- 20 19) METROPOLITAN U NIVERS ITY ' S H U MAN RIGHTS CENTER MAY 2020 Founder Angelina Jaffé Carbonell Advisory Board Angelina Jaffé Carbonell Rogelio Pérez-Perdomo Tamara Bechar Alter Executive Director and Head of the International Criminal Law Area Andrea Santacruz. Attorney, Summa Cum Laude (Unimet). Master’s Degree in Business Tax Management graduated with honors (Unimet). Specialization in Crime and Criminology Sciences at the Central University of Venezuela (UCV). Ms. Santacruz is currently pursuing a Doctorate in Law at the Andrés Bello Catholic University (UCAB). Professor and Head of the Department of Legal Studies at the Metropolitan University (Unimet) Deputy Director and Head of the Human Rigts Violations Area Victoria Capriles. Attorney (Unimet). Master’s Degree in Sociology of Law, Cum Laude (Oñati International Institute for the Sociology of Law). Master’s Degree in Politics & Government, Cum Laude (Unimet). Ms. Capriles is currently pursuing a Doctorate in Political Science at the Simón Bolívar University (USB). Professor at the Department of International Studies at the Metropolitan University (Unimet) Human Rights Violations Researchers Vanessa Castillo, Liberal Arts student Fabiana de Freitas, Liberal Arts student International Criminal Law Researchers Alberto Seijas, Liberal Arts and Law student Andreina Bermúdez, Liberal Arts and Law student Rodrigo Colmenares, Law student Translation Team Mernoely Marfisi, Modern Languages student Sara Fadi, Liberal Arts student Cover photos: Damary Avendaño and Dexy González (Sergio González). Zulmith Espinoza (Victoria Capriles). José Gregorio and Elvira Pernalete (Embassy of Canada in Venezuela). -

Venezuela: What Lies Ahead After Election Clinches Maduro’S Clean Sweep

Venezuela: What Lies Ahead after Election Clinches Maduro’s Clean Sweep Latin America Report N°85 | 21 December 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. One-sided Elections .......................................................................................................... 2 III. The Road Ahead for Government and Opposition .......................................................... 5 A. A Survival Strategy under Sanctions and COVID-19 ................................................. 5 B. Tensions in the Government Bloc ............................................................................. 7 C. A Divided Opposition ................................................................................................. 8 IV. Economic and Social Collapse .......................................................................................... 11 V. The New International Landscape ................................................................................... 13 A. How Could Biden Change U.S. Venezuela Policy? .................................................... 13 B. Maduro’s Allies ......................................................................................................... -

Universidad Católica Andrés Bello Facultad De Humanidades Y Educación Escuela De Comunicación Social Mención Artes Audiovisuales Trabajo De Grado

UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA ANDRÉS BELLO FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES Y EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA DE COMUNICACIÓN SOCIAL MENCIÓN ARTES AUDIOVISUALES TRABAJO DE GRADO “OJO CON LA CONSTANCIA” DOCUMENTAL SOBRE LA PERSECUCIÓN POLITICA A LEOPOLDO LÓPEZ Tesistas: Gilbert, Juan José Pulido Márquez, Helena Tutor: Ramírez, Carlos Eduardo Caracas; septiembre 2014 DEDICATORIA A Nuestras familias A todos los que luchan por un mejor país A Venezuela “Ojo con la Constancia” Todos los derechos para todos los Venezolanos Leopoldo López Juan José Gilbert Helena Pulido Márquez AGRADECIMIENTOS (Juan José Gilbert) Quiero agradecer a mi familia por haberme apoyado en todo momento. A mi vieja, mi hermana, mis tías, tíos, mis primas. A toda la increíble familia García. Los amo. A todos los que creyeron en este maravilloso proyecto. Carlos Ramírez, el mejor tutor de todos y quien fue de gran ayuda. Rhory, Ricardo, Roci, María Luisa, Alexandra. Diego Zambrano, lejos pero presente. Yeye la mejor del mundo; gracias por tanto. Y a todos los que colaboraron para que esto quedara increíble. Helena… Solo puedo decir que eres grande y estas destinada al éxito. Te quiero mucho. Sin embargo; esto va dedicado principalmente a mi abuelo, mi abuela, mi padrino y por supuesto a mi princesa hermosa, Emiliana. Viva Venezuela y Ojo con la Constancia. Juanjo AGRADECIMIENTOS (Helena Pulido) A mis papas quienes son el mayor apoyo que se pueda pedir; las personas que me dieron mi base, los primeros en creer en mis proyectos, los primeros en decir la verdad por más dura que sea, los que nunca dudan de mí y lo que puedo lograr, haciendo que cada día quiera ser mejor.