Sea to Sky LRMP Socio-Economic Base Case Update

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Podolak Multifunctional Riverscapes

Multifunctional Riverscapes: Stream restoration, Capability Brown’s water features, and artificial whitewater By Kristen Nicole Podolak A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor G. Mathias Kondolf, Chair Professor Louise Mozingo Professor Vincent H. Resh Spring 2012 i Abstract Multifunctional Riverscapes by Kristen Nicole Podolak Doctor of Philosophy in Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning University of California, Berkeley Professor G. Mathias Kondolf, Chair Society is investing in river restoration and urban river revitalization as a solution for sustainable development. Many of these river projects adopt a multifunctional planning and design approach that strives to meld ecological, aesthetic, and recreational functions. However our understanding of how to accomplish multifunctionality and how the different functions work together is incomplete. Numerous ecologically justified river restoration projects may actually be driven by aesthetic and recreational preferences that are largely unexamined. At the same time river projects originally designed for aesthetics or recreation are now attempting to integrate habitat and environmental considerations to make the rivers more sustainable. Through in-depth study of a variety of constructed river landscapes - including dense historical river bend designs, artificial whitewater, and urban stream restoration this dissertation analyzes how aesthetic, ecological, and recreational functions intersect and potentially conflict. To explore how aesthetic and biophysical processes work together in riverscapes, I explored the relationship between one ideal of beauty, an s-curve illustrated by William Hogarth in the 18th century and two sets of river designs: 18th century river designs in England and late 20th century river restoration designs in North America. -

Emergency Action Plan

EMERGENCY ACTION PLAN Rutherford Creek Whitewater Park BC Slalom Championships August 5-9, 2009 Emergency Phone Numbers: Emergency: 911 Ambulance (Pemberton): 604-894-6353 Police (Pemberton RCMP): 604-894-6634 Fire (Pemberton): 604-894-6412 Hospital (Pemberton Health Centre): 604-894-6633 Hospital (Whistler Health Care Centre): 604-932-4911 Blackcomb Helicopters: 604-938-1700 Locations of Phones: 1. Rutherford Creek Power facility on-site 2. Cell phone(s) at Headquarter’s building Facility Location Details: Rutherford Power, 8km South of Pemberton on Highway 99, at Rutherford Creek Bridge Rutherford Whitewater Park Facility Contact Numbers: Power house phone 604-894-1766 Don Gamache (Plant Supervisor) cell phone 604-935-7749 Bob Noldner cell phone 604-905-9477 Gary Carr cell phone 604-935-4666 Charge Person/Incident Commander: Call Person: Toby Roessingh (403) 338-1153, Aug 5-7 Andrew Mylly (604) 329-3305, Aug 8-9 Mary-Jane Abbot, Exec. Director, CKBC Phone 604-465-5268 Charge Person Alternate 1: Call Person Alternate 1: Kurt Braunlich (360) 535-3495, Aug 5-7 Erin Hart (604) 535-8864, Aug 8-9 Elizabeth Grimaldi, President, CCE Home phone 604-858-0692 Charge Person Alternate 2: First Aid Coordinator: Don Gamache, Plant Supervisor Work phone 604-894-1766 None: Event participants should be prepared Cell phone 604-935-7749 to offer first aid. 25 July 2009 Page 1 of 2 EMERGENCY ACTION PLAN Rutherford Creek Whitewater Park BC Slalom Championships August 5-9, 2009 Avaliable Rescue & First Aid Supplies (Headquarters Building: Backboard with straps -

Tnf Tnf Hns Tnf Atlin

Mount Foster !( 5500 6000 5000 6000 5500 4500 6500 5000 5000 7000 6000 Mount Van!( Wagenen 5500 6000 MOD Jul 10 4500 5000 4000 6500 7000 4500 3500 6500 5000 5000 7000 FUL 5500 7000 5500 2500 4500 Mount Hoffman!( 2000 6500 4000 4000 5000 7500 4500 1500 3500 3500 5000 ª« 4000 No 1000 urs e R iv 4500 5500 e Mount 5000 r FUL Cleveland ª« 5500 !( 3500 LIM 4500 LIM 4500 KLONDIKE GOLD ª« 6000 5500 6000 3000 6000 6500 4500 3500 5000 6000 RUSH NATIONAL ª« 6000 5500 TONGASS 4500 6500 4000 HISTORICAL PARK 5000 ª« MOD NATIONAL 6500 3000 Jul 10 AKAA006272 FOREST"J Mount Carmack!( 4500 3000 r 6000 5500 6000 ª« e v i Laughton Porcupine Hill 5000 !( R 6000 6000 Glacier 5500 y Mount ª« a 4000 AKAA006529C Clifford w Goat 5500 !( g Mount Yeatman!( T a Lake 6000 a k 5500 6000 ª« S i 6500 y a We A B Mountain!( st R 4000 4500 C "J r i ª« e v 3500 e AKAA006529B 3000 Boundary k e 5000 500 6000 5500 r 6000 Peak!( 111 ª« 3500 ª« "J 5500 "J 5500 MOD Jul 10 6500 Lost Lake ª« ª« Twin E 5000 MOD Jul 10 ast Fork Skagway River 5000 Dewey 6000 k AKAA006529A ee Peaks 5500 r !( n C ª« 4500 Mount!( Hefty HNS 3000 lso 5500 "J 5000 e CRI FUL 3500 N ª« 4500 r e ª« R 4000 ª« e v Icy id i 4500 ª« ª« Cr 5500 R ee Face Mountain!( 5500 k 6000 "J t Lake 5000 6000 Skagway Boundary !( Peak 109 o 5500 ª« " 5500 o 5000 k 4500 AKAA006528A 6000 "J il p h CRI C LIM De 4000 LIM wey C 4500 B p ree 5500 u k r Boundary !( Peak 108 ro 6000 6500 5000 Creek Creek "J er d "J y 5000 5500 n S LIM 5500 4000 5000 Mount Harding 5000 !( F 4000 e K r e 4500 as b i 4500 e d Mount!( Bagot e a 4500 y 2000 -

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC)

Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Summits on the Air USA - Colorado (WØC) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S46.1 Issue number 3.2 Date of issue 15-June-2021 Participation start date 01-May-2010 Authorised Date: 15-June-2021 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Matt Schnizer KØMOS Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Page 1 of 11 Document S46.1 V3.2 Summits on the Air – ARM for USA - Colorado (WØC) Change Control Date Version Details 01-May-10 1.0 First formal issue of this document 01-Aug-11 2.0 Updated Version including all qualified CO Peaks, North Dakota, and South Dakota Peaks 01-Dec-11 2.1 Corrections to document for consistency between sections. 31-Mar-14 2.2 Convert WØ to WØC for Colorado only Association. Remove South Dakota and North Dakota Regions. Minor grammatical changes. Clarification of SOTA Rule 3.7.3 “Final Access”. Matt Schnizer K0MOS becomes the new W0C Association Manager. 04/30/16 2.3 Updated Disclaimer Updated 2.0 Program Derivation: Changed prominence from 500 ft to 150m (492 ft) Updated 3.0 General information: Added valid FCC license Corrected conversion factor (ft to m) and recalculated all summits 1-Apr-2017 3.0 Acquired new Summit List from ListsofJohn.com: 64 new summits (37 for P500 ft to P150 m change and 27 new) and 3 deletes due to prom corrections. -

ATHLETE SELECTION PROCEDURES: USA Canoe

ATHLETE SELECTION PROCEDURES: USA Canoe Slalom National Team to compete at the 2018 ICF Canoe Slalom WorlD Cups, 2018 ICF Canoe Slalom WorlD Championship, 2018/19 ICF Canoe Slalom Ranking Races, 2018/19 COPAC Canoe Slalom Pan American Championships, 2018 ICF Canoe Slalom Junior & U23 World Championships 1. ELIGIBILITY: In orDer to be considereD for eligibility for the USA Canoe Slalom National Team, athletes must meet the following minimum eligibility requirements: 1.1. Citizenship: 1.1.1. Citizenship is not necessarily a requirement of eligibility for the USA Canoe Slalom National Team. Athletes must meet ICF eligibility rules for competition. (These rules are outlined in the ICF Slalom Competition Rules, Section 3 – Competitors.) 1.2. Minimum International Federation (IF) and/or Continental Federation (CF) standards for participation (if any): 1.2.1. Eligibility for the ACA Canoe Slalom National Team Trials will be goVerneD by the current International Canoe FeDeration (ICF) Canoe Slalom Competition Rules anD the ACA Canoe Slalom Competition Rules, Article 3: - ICF Canoe Slalom Competition Rules: www.americancanoe.org/ICFslalomrules – ACA Canoe Slalom Competition Rules: www.americancanoe.org/ACAslalomrules 1.3. Other requirements (if any): 1.3.1. Athletes must be members in gooD stanDing with ACA at the time of the start of the Trials. 1.3.2. C2M and C2MX teams shall qualify only as a team and not as indiViduals. 1 www.americancanoe.org/Competition February 15, 2018 2. SELECTION EVENT: Via the proceDures set forth herein, athletes will qualify for the 2018 ICF Canoe Slalom WorlD Championships, U23 WorlD Championships, anD WorlD Cup teams at the selection eVent shown below. -

Technical Plan December 2019 Public Hearing Draft

Technical Plan December 2019 Public Hearing Draft Beautiful, diverse Skagway, place for everyone Bliss and Gunalchéesh Cynthia Tronrud We create Skagway Oddballs and adventurers Living out our dreams Wendy Anderson Forever small town Skies shushing on snow through birch Howling his love for all Robbie Graham Acknowledgements PLANNING COMMISSION ASSEMBLY Matt Deach, Chair Mayor Andrew Cremata Philip Clark Steve Burnham Jr., Vice Mayor Gary Hisman David Brena Richard Outcalt Jay Burnham Joseph Rau Orion Hanson Assembly Liaison, Orion Hanson Dan Henry Dustin Stone Tim Cochran (former) Project Manager Shane Rupprecht, Skagway Permitting Official Special Thanks to the Following Individuals who Graciously Provided Information and Answered Countless Questions during Plan Development Emily Deach, Borough Clerk Heather Rodig, Borough Treasurer Leola Mauldin, Tax Clerk Kaitlyn Jared, Skagway Development Corporation, Executive Director Sara Kinjo-Hischer, Skagway Traditional Council, Tribal Administrator This Plan Could Not Have Been Written Without The Assistance of Municipal Staff, Including: Alanna Lawson, Accounts Payable/Receivable Katherine Nelson, Recreation Center Director Clerk Lea Mauldin, Tax Clerk Brad Ryan, Borough Manager Matt Deach, Water / Wastewater Superintendent Cody Jennings, Tourism Director, Convention Matt O'Boyle, Harbormaster & Visitors Bureau Michelle Gihl, Assistant to the Manager/ Emily Deach, Borough Clerk Deputy Clerk Emily Rauscher, Emergency Services Administrator Ray Leggett, Police Chief Gregg Kollasch, Lead Groundskeeper -

Patricia Palmer Lee PRG 1722 Special List POSTCARDS INDEX

___________________________________________________________ ______________________ Patricia Palmer Lee PRG 1722 Special List POSTCARDS INDEX 1993 to 2014 NO. DATE SUBJECT POSTMARK STAMPS A1 05.07.1993 Ramsgate Beach, Botany Bay Sydney Parma Wallaby A2 09.07.1993 Bondi Beach Surf Eastern Suburbs Ghost Bat A3 13.07.1993 Autumn Foliage, Blue Mountains Eastern Suburbs Tasmanian Herit Train A4 20.07.1993 Baha'i Temple, Ingleside Eastern Suburbs Silver City Comet A5 27.07.1993 Harbour Bridge from McMahon's Point Eastern Suburbs Kuranda Tourist Train A6 04.08.1993 Winter Sunset, Cooks River, Tempe Eastern Suburbs Long-tailed Dunnart A7 10.08.1993 Henry Lawson Memorial, Domain Eastern Suburbs Little Pygmy-Possum A8 17.08.1993 Berry Island, Parramatta River Rushcutters Bay Ghost Bat A9 24.08.1993 Story Bridge, Brisbane River Eastern Suburbs Parma Wallaby A10 28.08.1993 Stradbroke Island, Moreton Bay Qld Cootamundra Long-tailed Dunnart A11 31.08.1993 Rainforest, Brisbane Botanical Gardens Yass Little Pygmy-Possum A12 05.09.1993 Dinosaur Exhibit, Brisbane Museum Eastern Suburbs Ghost Bat A13 10.09.1993 Wattle Festival Time, Cootamundra Eastern Suburbs Squirrel Glider A14 14.09.1993 Davidson Nat Park, Middle Harbour Eastern Suburbs Dusky Hopping-Mouse A15 17.09.1993 Cooma Cottage, Yass Eastern Suburbs Parma Wallaby A16 21.09.1993 Bicentennial Park, Homebush Bay Eastern Suburbs The Ghan A17 24.09.1993 Rainbow, North Coast NSW Eastern Suburbs Long-Tailed Dunnart A18 28.09.1993 Sphinx Monument, Kuring-gai Chase NP Canberra Little Pygmy-Possum A19 01.10.1993 -

Les Numéros En Bleu Renvoient Aux Cartes

494 Index Les numéros en bleu renvoient aux cartes. 12 Foot Davis Memorial Site (Peace River) 416 Alberta Legislature Building (Edmonton) 396 +15 (Calgary) 322 Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions (Stettler) 386 17th Avenue (Calgary) 329 Alberta’s Dream (Calgary) 322 17th Avenue Retail and Entertainment District Alberta Sports Hall of Fame & Museum (Red (Calgary) 329 Deer) 384 21st Street East (Saskatoon) 432 Alberta Theatre Projects (Calgary) 328 30th Avenue (Vernon) 209 Albert Block (Winnipeg) 451 96th Street (Edmonton) 394 Alert Bay (île de Vancouver) 147 104th Street (Edmonton) 396 Alexandra Bridge (sud C.-B.) 179 124th Street (Edmonton) 403 Alexandra Park (Vancouver) 76 Alfred Hole Goose Sanctuary (Manitoba) 463 Alice Lake Provincial Park (sud C.-B.) 169 A Allen Sapp Gallery (The Battlefords) 440 Alpha Lake (Whistler) 172 Abkhazi Garden (Victoria) 114 Alta Lake (Whistler) 172 Accès 476 Altona (Manitoba) 464 A Achats 478 Ambleside Park (West Vancouver) 84 Active Pass Lighthouse (Mayne Island) 154 Amérindiens 39 Aéroports Amphitrite Lighthouse (Ucluelet) 133 Calgary International Airport 318 Anarchist View Point (Osoyoos) 192 Campbell River Airport 100 Angel Glacier (promenade des Glaciers) 296 INDEX Canadian Rockies International Airport (Cranbrook) 263 Anglin Lake (Saskatchewan) 442 Comox Valley Airport 100 Animaux de compagnie 479 Dawson Creek Regional Airport 226 Annette Lake (environs de Jasper) 305 Edmonton International Airport 392 Aquabus (Vancouver) 52 Kelowna International Airport 158 Archipel Haida Gwaii (nord C.-B.) 254 Lethbridge Airport 348 Architecture 43 Masset Municipal Airport (Archipel Haida Gwaii) 226 Argent 479 Medicine Hat Regional Airport 348 Art Gallery of Alberta (Edmonton) 394 Nanaimo Airport 100 Northern Rockies Municipal Airport (Fort Art Gallery of Grande Prairie (Grande Prairie) 418 Nelson) 226 Art Gallery of Greater Victoria (Victoria) 114 North Peace Regional Airport (Fort St. -

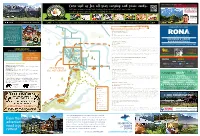

Connection Call 604-230-8167 [email protected] Frankingham.Com

YOUR PEMBERTON Real Estate connection Call 604-230-8167 [email protected] FrankIngham.com FRANK INGHAM GREAT GOLF, FANTASTIC FOOD, EPIC VIEWS. EVERYONE WELCOME! R E A L E S T A T E Pemberton Resident For Over 20 Years 604-894-6197 | pembertongolf.com | 1730 Airport RD Relax and unwind in an exquisite PEMBERTON VALLEY yellow cedar log home. Six PEMBERTON & AREA HIKING TRAILS unique guest bedrooms with private bathrooms, full breakfast ONE MILE LAKE LOOP 1 and outdoor hot tub. Ideal for 1.45km loop/Approx. 30 minutes groups, families and corporate Easy retreats. The Log House B&B 1.3km / 1 minute by vehicle from Pemberton Inn is close to all amenities and PEMBERTON LOCAL. INDEPENDENT. AUTHENTIC. enjoys stunning mountain views. MEADOWS RD. Closest to the Village, the One Mile Lake Loop Trail is an easy loop around the lake that is wheelchair accessible. COLLINS RD. Washroom facilities available at One Mile Lake. HARDWARE & LUMBER 1357 Elmwood Drive N CALL: 604-894-6000 LUMPY’S EPIC TRAIL 2 BUILDING MATERIALS EMAIL: [email protected] 9km loop/ Approx. 4 hours WEB: loghouseinn.com Moderate 7426 Prospect street, Pemberton BC | 604 894 6240 URDAL RD. 1.3km / 1 minute by vehicle from Pemberton The trail is actually a dedicated mountain bike trail but in recent years hikers and mountain runners have used it to gain PROSPECT ST. access to the top of Signal Hill Mountain. The trail is easily accessed from One Mile Lake. Follow the Sea to Sky Trail to EMERGENCIES: 1–1392 Portage Road IN THE CASE OF AN EMERGENCY ALWAYS CALL 911 URCAL-FRASER TRAIL Nairn Falls and turn left on to Nairn One Mile/Lumpy’s Epic trail. -

Gazetteer of Yukon

Gazetteer of Yukon Updated: May 1, 2021 Yukon Geographical Names Program Tourism and Culture Yukon Geographical Place Names Program The Yukon Geographical Place Names Program manages naming and renaming of Yukon places and geographical features. This includes lakes, rivers, creeks and mountains. Anyone can submit place names that reflect our diverse cultures, history and landscape. Yukon Geographical Place Names Board The Yukon Geographical Place Names Board (YGPNB) approves the applications and recommends decisions to the Minister of Tourism and Culture. The YGPNB meets at least twice a year to decide upon proposed names. The Board has six members appointed by the Minister of Tourism and Culture, three of whom are nominated by the Council of Yukon First Nations. Yukon Geographical Place Names Database The Heritage Resources Unit maintains and updates the Yukon Geographical Place Names Database of over 6,000 records. The Unit administers the program for naming and changing the names of Yukon place names and geographical features such as lakes, rivers, creek and mountains, approved by the Minister of Tourism and Culture, based on recommendations of the YGPNB. Guiding Principles The YGPNB bases its decisions on whether to recommend or rescind a particular place name to the Minister of Tourism and Culture on a number of principles and procedures first established by the Geographic Names Board of Canada. First priority shall be given to names with When proposing names for previously long-standing local usage by the general unnamed features—those for which no public, particularly indigenous names in local names exist—preference shall be the local First Nation language. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 2 • Canoe Kayak BC Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2018-19 2 • Canoe Kayak BC Annual Report CKBC Clubs Throughout B.C. CLUB MEMBERSHIP Twenty-six paddling clubs registered with CKBC in 2017-18 and we welcomed two new clubs: Creekside Paddling Club in Vancouver Skeena Paddle Club in Terrace CKBC Membership Through the Years 2018 2017 2016 INDIVIDUAL MEMBERSHIP 2015 Aboriginal: 97 2014 Canoe Polo: 33 2013 Coach: 12 2012 Competitive: 256 2011 Day Camp: 983 2010 Dragon Boat: 101 2009 Marathon: 30 2008 Official: 2 2007 Outrigger: 53 2006 Paddle All: 20 2005 Recreational: 1,025 2004 School Program: 2,596 2003 SUP: 46 2002 Volunteer: 54 2001 Whitewater: 103 2000 1999 1,000 2,000 3,000 4,000 5,000 6,000 3 • Canoe Kayak BC Annual Report CKBC launched a new website in January 2019. Mary Jane Abbott announced retirement from Canoe The new site offers a fresh new look and easier navigation and includes a responsive design. Kayak BC www.canoekayakbc.ca CKBC’s Facebook posts had over 1,500 reactions this year. In total 1,470 individuals received paddling updates on Facebook. www.facebook.com/pages/CanoeKayak-BC Following 20 years at the helm of Canoe Kayak BC, Mary Jane Abbott announced her retirement from the association in January. MJ was hired in 1999 at Canoe Kayak BC as the association’s only employee, a part-time Executive Director, There were 969 individuals getting their CKBC From there she guided CKBC’s growth to a full-time staff, including paddling news on Twitter. Provincial Coach, Sport Development Coordinator, Regional Coaches and a www.twitter.com/CanoeKayakBC Communications lead. -

Nevada, California & Americana the Library of Clint Maish

Sale 465 Thursday, October 20, 2011 11:00 AM Nevada, California & Americana The Library of Clint Maish with Early Kentucky Documents & additional material Auction Preview Tuesday, October 18, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Wednesday, October 19, 9:00 am to 5:00 pm Thursday, October 20, 9:00 am to 11:00 am Other showings by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDING AVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/ realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www. pbagalleries.com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale.