Ken James Stavrevsky 17 May 1995 Medical Ethics: a Reflection On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grade 2 Lesson

Unit 5 "Observances" Lesson 27 Pascha Objective: The students will review the events of Lesson Plan Overview Holy Week and Pascha and be able to tell the story of the women coming to the tomb. Opening: Paschal Greeting [Refer to the "Liturgical Prayers Ac- For the Catechist cording to Jurisdictions" in the section "Introduction to Grade 2" for the cor- Each book of the series offers a lesson on Pascha. rect wording to use in your parish.] The students should be quite familiar with Pascha as celebrating the day Jesus rose from the dead. In Introduction: Discussion of the story of this book the lesson expands the basic teaching to the Myrrh-bearers folded white include more of the story. There are two names for Need: cloth the children to learn: Golgotha and Joseph of Arimathea. They are also introduced to the other Read Text Aloud: Have students read text icon of the Resurrection: The Myrrh-bearing aloud. Women. As with all lessons on the Resurrection, it presents the Good News that we will be fully unit- Activity Tracks: ed with God in heaven one day. Choose a basic, group, or craft activity to reinforce the lesson (detailed on the pages Joseph of Arimathea. The name of Joseph should that follow). be familiar to the students from the procession with the shroud on Good and Holy Friday. The • Basic: Jesus, Our Light hymn speaks of Joseph placing the body in a new tomb. This is noted also in the Gospel to say that • Group: Interactive Story Circle only Jesus was in the tomb. -

Grade 1 Lesson

Unit 6 “Observances” Lesson 27 Pascha Objective: The students will be able to identify Lesson Plan Overview Pascha as the day we celebrate that Jesus Christ rose from the dead. They will be able to say "Christ is risen!" Opening: Paschal Greeting and "Indeed He is risen!" Refer to Prayers According to Jurisdic- tions in the Introduction to Grade 1 and For the Catechist use wording approved by your jurisdic- The feast of Pascha is the climax of the Church year. It tion. is the Feast of Feasts, the foreshadowing of our own resurrection one day. In words and images the lesson Introduction: Study of "Harrowing of attempts to surround the students with the experience of Hades" Icon Need: Resurrection Icon Pascha. Let them share their own experiences and Puzzle (large version) memories of Pascha. Let them reflect on its meaning— that after death we will live forever with God and the Read Text Aloud: Ask questions noted on faithful who have gone before. The icon is a perfect the following pages as text is being read. teaching tool for the deep and rich theology of the Resurrection. Activity Tracks: Icon of the Resurrection. There are two icons which Choose a basic, group, or craft activity to celebrate our Lord's Resurrection. The "Myrrh-bearing reinforce the lesson (detailed on the pages Women," showing the women on their way to the tomb, that follow). and the "Descent into Hades," sometimes called the "Harrowing of Hades." The latter is the more commonly •Basic 1: Symbols of Pascha used. •Basic 2: “I Know About the Resurrection” Background Reading •Group: Paschal Greeting Banner (Direct quotations from the sources noted.) •Craft: Resurrection Icon Puzzle The Icon of the Resurrection "The Icon of the Resurrection is either the 'Descent Into Closing: Paschal Greeting Hades' or the 'Myrrh-bearing Women.' The Icon of the Descent into Hades shows Christ as the Life-giver. -

6Th SUNDAY of EASTER at HOME –––––––––––––––– LITURGY

THE PARISH OF S. PAUL w. S. MARK Meaning of the Paschal Greeting DEPTFORD Greek = English ‘anglo-catholic, inclusive, committed to prayer & justice.’ Χριστός ἀνέστη! = Christ is risen! http://www.achurchnearyou.com/deptford-st-paul The Rector & Parish Priest: Fr Paul Butler Ἀληθῶς ανέστη! = Truly he is risen! tel: 0208 6927449 email: [email protected] The Kyrie Eleison Like Mary at the empty tomb, 6th SUNDAY we fail to grasp the wonder of your presence. of EASTER Lord, have mercy. Lord, have mercy. at HOME –––––––––––––––– Like the disciples behind locked doors, we are afraid to be seen as your followers. LITURGY OF Christ, have mercy. SPIRITUAL Christ, have mercy. COMUNION Like Thomas in the upper room, –––––––––––––––––– we are slow to believe. th 17 May 2020 Lord, have mercy. 10.30am Lord, have mercy. Gloria in excelsis If a household are praying Glory to God in the highest, together one person may act as and on earth peace to people of good will. leader & the others as the We praise you, we bless you, congregation and they join in the we adore you, we glorify you, sections in bold type. If alone we give you thanks for your great glory, read all the words aloud. Lord God, heavenly King, O God, almighty Father. Prayer of Preparation Lord Jesus Christ, Only Begotten Son, Almighty God, Lord God, Lamb of God, Son of the Father, to whom all hearts are you take away the sins of the world, open, all desires known, have mercy on us; and from whom no you take away the sins of the world, secrets are hidden: receive our prayer; cleanse the thoughts you are seated at the right hand of the Father, of our hearts have mercy on us. -

Living with Christ Great Lent at Home

Living with Christ Great Lent at Home O LORD and Master of my life, grant that I may not be afflicted with a spirit of sloth, inquisitiveness, ambition and vain talking. Instead, bestow upon me, Your servant, a spirit of purity, humility, patience and love. Yes, O Lord and King, grant me the grace to see my own sins and not to judge my brethren. For you are blessed forever and ever. Amen. Melkite Greek-Catholic Eparchy of Newton Office of Educational Services First Monday Today we begin the Great Fast. Our Church has four Fasts every year. The one before Holy Week and Pascha is called “Great” because it is Introduction the longest and the most important of them all. Children need frequent reinforcement of any action or idea we wish to The Great Fast lasts for 40 days, reminding us that the Lord Jesus convey. To help our children grasp the concept of the Great Fast and fasted for 40 days after His baptism in the Jordan (read Luke 4:2). make it their own, we have designed the following daily program Another holy person who fasted for forty days is Moses, when he providing concepts and activities for each day of the Fast, for Holy received the Ten Commandments (read Exodus 34:28). Week and for Bright Week. Many times during the year we forget God and other people. We think It is suggested that you print each daily selection and discuss it. Family about ourselves and what we want. During the Great Fast we try to meal times are considered the most accessible time for such change by thinking more about God and others. -

Patriarchal Paschal Encyclical 2020, English

Patriarchal Pascha Encyclical 2020 p. 1 The Serbian Orthodox Church to her spiritual children at Pascha, 2020 +IRINEJ By the Grace of God Orthodox Archbishop of Pec, Metropolitan of Belgrade Karlovci and Serbian Patriarch, with all the Hierarchs of the Serbian Orthodox Church to all the clergy, monastics, and all the sons and daughters of our Holy Church: grace, mercy and peace from God the Father, and our Lord Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit, with the joyous Paschal greeting: Christ is Risen! This is the day of Resurrection; let us be illumined by the feast! Let us embrace each other joyously! Let us say even to those who hate us: Let us forgive all by the Resurrection; and so let us cry: Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life! [The Stichera of Pascha from Matins] Here we are, dear brothers and sisters and dear spiritual children, in the festivity and joy of the great Feast Day: Pascha. Today is the Feast Day of the Resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ. Let us rejoice and celebrate! Pascha is our greatest feast day, the feast of the victory of Life over death, God over Satan, Man, in Christ Jesus, over sin. Christ is risen from the dead! Let us say it to all and make glad all and everyone, even those who hate Him, the Resurrected God Man, and us, His inheritance here on earth, and those who do not believe and still doubt that He is the Redeemer and Savior of the world. -

Dictionary of Religious Terms

IMPORTANT INFORMATION – Please Read! his lexicon began as a personal project to assist me in my efforts to learn more about my faith. All too often in my T readings I was coming across unfamiliar words, frequently in languages other than English. I began compiling a “small” list of terms and explanations to use as a reference. Since I was putting this together for my own use I usually copied explanations word for word, occasionally making a few modifications. As the list grew I began having trouble filling in some gaps. I turned to some friends for help. They in turn suggested this lexicon would be a good resource for the members of the Typikon and Ustav lists @yahoogroups.com and that list members maybe willing to help fill the gaps and sort out some other trouble spots. So, I present to you my lexicon. Here are some details: This draft version, as of 19 December 2001, contains 418 entries; Terms are given in transliterated Greek, Greek, Old Slavonic, Ukrainian, and English, followed by definitions/explanations; The terms are sorted alphabetically by “English”; The Greek transliteration is inconsistent as my sources use different systems; This document was created with MS Word 97 and converted to pdf with Adobe Acrobat 5.0 (can be opened with Acrobat Reader 4.0); Times New Roman is used for all texts except the Old Slavonic entries for which I used a font called IZHITSA; My sources are listed at the end of the lexicon; Permission has not been obtained from the authors so I ask that this lexicon remain for private use only. -

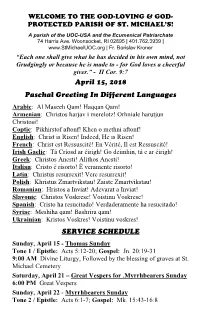

April 15, 2018 Paschal Greeting in Different Languages SERVICE SCHEDULE

WELCOME TO THE GOD - LOVING & GOD - PROTECTED PARISH OF ST. MICHAEL’S! A parish of the UOC - USA and the Ecumenical Patriarchate 74 Harris Ave. Woonsocket, RI 02895 | 401.762.3939 | www.StMichaelUOC.org | Fr. Borislav Kroner “Each one shall give what he has decided in his own mind, not Grudgingly or because he is made to - for God loves a cheerful giver.” - II Cor. 9:7 April 15 , 2018 Paschal Greeting In Different Languages Arabic : Al Maseeh Qam! Haqqan Qam! Armenian : Christos harjav i merelotz! Orhniale harutjun Christosi! Coptic : Pikhirstof aftonf! Khen o methni aftonf! English : Christ is Risen! Indeed, He is Risen! French : Christ est Ressuscité! En Vérité, Il est Ressuscité! Irish Gaelic : Tá Críosd ar éirigh! Go deimhin, tá e ar éirigh! Greek : Christos Anesti! Alithos Anesti! Italian : Cristo è risorto! È veramente risorto! Latin : Christus resurrexit! Vere resurrexit! Polish : Khristus Zmartvikstau! Zaiste Zmartvikstau! Romanian : Hristos a Inviat! Adevarat a Inviat! Slavonic : Christos Voskrese! Voistinu Voskrese! Spanish : Cristo ha resucitado! Verdaderamente ha resucitado! Syriac : Meshiha qam! Bashrira qam! Ukrainian : Kristos Voskres! Voistinu voskres! SERVICE SCHEDULE Sunday, April 15 - Thomas Sunday Tone 1 / Epistle : Acts 5:12 - 20 ; Gospel: Jn. 20:19 - 31 9:00 AM Divine Liturgy, Followed by the blessing of g raves at St. Michael Cemetery Saturday, April 21 – Great Vespers for .Myrrhbearers Sunday 6:00 PM Great Vespers Sunday, April 22 - Myrrhbearers Sunday Tone 2 / Epistle: Acts 6:1 - 7 ; Gospel: Mk. 15:43 - 16:8 9:00 AM Divine Liturgy, Followed by the Sviachene Dinner / The Ladies Sodality of St. Michael’s Patronal Feast Day Saturday, April 28 – Great Vespers for Paralytic Sunday 6:00 PM Great Vespers Sunday, April 29 - Paralytic Sunday Tone 3 / Epistle: Acts 9:3 2 - 42 ; Gospel: Jn. -

Second Sunday of Pascha: Thomas Sunday

THE ORTHODOX CHURCH OF SAINT ELIZABETH THE NEW-MARTYR Volume XX Number 33 15 / 28 April 2019 HOLY & GREAT SUNDAY OF PASCHA _______________________________________________________________________________________________ SCHEDULE OF SERVICES FASTING DAYS THIS WEEK FOR PASCHA AND BRIGHT WEEK Bright Week (the week following Holy Pascha) is an HOLY PASCHA immediate joyful extension of the Sunday of Pascha. Saturday, 27 April (14 April, o.s.) The services on each day of this glorious week are 11:15 PM Midnight Office & Procession substantially the same as on the Sunday of Pascha. Sunday, 28 April (15 April, o.s.) Because of our overflowing joy in the Resurrection of 12:01 AM Paschal Matins & Divine Liturgy; our Saviour, no fasting is permitted during this week. Paschal Trapeza (Meal) All foods may be eaten, even on Wednesday and Friday. BRIGHT MONDAY Sunday, 28 April (15 April, o.s.) 2:00 PM Agape Vespers; Children’s Egg Hunt THIS WEEK’S ANNOUNCEMENTS Monday, 29 April (16 April, o.s.) 9:15 AM Paschal Hours MANY THANKS: 9:30 AM Divine Liturgy . To our three wonderful Deacons, Fr Seraphim Komleski, Fr Steven Barker, and Fr Stephanos 2ND SUNDAY OF PASCHA: Thomas Sunday Bibas who served the church services and were Saturday, 4 May (21 April, o.s.) such a help to Fr David during Great Lent, and 6:00 PM Vigil Service; Holy Week; Confessions . To Claudia Maxey and many others who helped Sunday, 5 May (22 April, o.s.) with the singing at every service in Great Lent, 9:10 AM Third and Sixth Hours Holy Week, Pascha, and Bright Week; 9:30 AM Divine Liturgy; . -

ERASMUS+ Learning Families Project

Project Number: 2017-1-IT02-KA201-036784 Table of Contents 1. Eastern Catholicism .................................................................................... 3 1.1 Introduction.......................................................................................... 3 1.2 Great blessing of the waters ................................................................. 4 1.3 πάνα κλίσε (long and ancient prayer of Christianity) of the Dormition .. 6 1.4 Celebrating the Saint Apostles Peter and Paul ....................................... 7 2. Judaism ...................................................................................................... 9 2.1. Introduction......................................................................................... 9 2.2. Shavuot ............................................................................................... 9 2.3. Sukkot ................................................................................................ 11 2.4. Rosh Hashana ..................................................................................... 13 3. Roman Catholicism .................................................................................... 15 3.1. The washing of feet ............................................................................ 16 3.2. Baptism .............................................................................................. 18 3.3. Midnight mass .................................................................................... 21 4. Eastern Orthodoxy .................................................................................... -

ORTHODOX EASTER Inclusive Employer Guide

ORTHODOX EASTER Inclusive Employer Guide EQUITY · DIVERSITY · INCLUSION WHAT IS ORTHODOX EASTER? Orthodox Easter is the celebration of Jesus’ resurrection, also known as Pascha. Orthodox Christian tradition, which originated in Eastern and South-Eastern Europe, celebrates Pascha in accordance with the Julian calendar, as opposed to Western churches which follow the Gregorian calendar. This is why Orthodox Easter falls on a different date to Easter Sunday. This year, Orthodox Holy Friday (Good Friday, focusing on Jesus’ death), falls on April 17 while Orthodox Easter Sunday falls on April 19. How is it observed? Pascha is an important event in the church calendar in the Orthodox Church. Many Orthodox Christians attend church services during the Holy Week that leads up to Easter Sunday, especially on Holy Friday. For many Orthodox Christians, Holy Friday is a strict day of fasting, and some Orthodox churches may have a Good Friday liturgy in the afternoons or evenings. The Easter Sunday church liturgy is joyous as it celebrates Jesus Christ’s resurrection, as told in the Christian bible. The period before Easter, known as Lent, is also a time of strict fasting and self-reflection. Orthodox Christians in Canada observe this fasting ritual before celebrating Easter Sunday with a feast, where meat and dairy products can be eaten again. Another tradition observed in Orthodox Christian churches is the blessing of food baskets. The baskets are usually filled with bread, cheese, meat, eggs, butter, salt, and other types of food used for Paschal celebrations. Symbols of Orthodox Easter include hard boiled eggs, dyed red to reference the blood of Christ. -

Sunday Bulletin

V. Rev. Father Nabil L. Hanna, Pastor (317) 919-0841 • [email protected] Rev. James A. Childs, Deacon (317) 626-3943 • [email protected] 10748 E. 116th Street • Fishers, Indiana 46037 Rev. Joseph S. Olas, Deacon (317) 845-7755 • www.stgindy.org (317) 201-8151 • [email protected] A Parish of the Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of North America • Diocese of Toledo and the Midwest His Eminence Metropolitan JOSEPH, Archbishop of New York and Metropolitan of all North America His Grace Bishop ANTHONY, Auxiliary Bishop of the Diocese of Toledo TONE 4 MAY 26, 2019 EOTHINON 7 FIFTH SUNDAY OF PASCHA: THE SAMARITAN WOMAN AND POST-FEAST OF MID-PENTECOST APOSTLES KARPOS AND ALPHAIOS OF THE SEVENTY SINESIOS, BISHOP OF CARPASIA IN CYPRUS • NEW-MARTYR ALEXANDER OF THESSALONICA AUGUSTINE OF CANTERBURY, EVANGELIZER OF ENGLAND At the sixth hour Thou didst come to the well, O Fountain of wonder, to ensnare the fruit of Eve; for that one, at the very same hour, had been driven from paradise by the serpent’s temptation. Then the Samaritan woman came to draw water, and when Thou didst see her, O Savior, Thou didst say to her: Give Me water to drink, and I will fill thee with everlasting water. And that chaste woman hastened at once to the city and said to the crowds: Come and see Christ the Lord, the Savior of our souls. LITURGY VARIATIONS PASCHAL GREETING / RESPONSE English: Christ is risen! / Truly He is risen! Arabic: Al-Maseeh qam! / Háqqan qam! Greek: Christós anéste! / Alethós anéste! Slavonic: Christós voskrése! / Vo-ístinu voskrése! -

Greek Orthodox Church of the Holy Trinity

Great & Holy Pascha, May 2, 2021 Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople: www.patriarchate.org Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America Website: www.goarch.org Greek Orthodox Metropolis of Atlanta Website: www.atlanta.goarch.org St. Christopher Hellenic Orthodox Church Website: www.saintchristopherhoc.org St. Christopher Hellenic Orthodox Church 313 Dividend Drive, Suite 210 Peachtree City, Georgia 30269 Very Rev. Fr. George J. Tsahakis, Chancellor Liturgical Guide for Sunday, May 2, 2021 ON THE HOLY AND GREAT SUNDAY OF PASCHA WE CELEBRATE THE VERY LIFE-BEARING RESURRECTION OF OUR LORD AND GOD AND SAVIOR JESUS CHRIST. WE ALSO COMMEMORATE the Removal of the Relics of St. Athanasius the Great; Hesperos & Zoe the Righteous; Boris, King & Enlightener of Bulgaria (Michael in Baptism); and Jordan the Wonderworker. To Him be the glory and the dominion to the ages of ages. Amen. Through the holy intercessions of the saints, O God, have mercy on us and save us. Amen. Thank You for Your Understanding We welcome our parishioners who pre-registered and are attending services in person today and we also welcome those who are viewing our online video streaming at home. Let us comply with the guidelines we have provided everyone. We appreciate your kind understanding in following them. Fr. George is deeply appreciative to you and all who are assisting during worship services. Please consider that only baptized and chrismated Orthodox Christians in canonical good standing may approach for Holy Communion. All are invited to partake of the Antidoron ("instead of the gifts") distributed at the conclusion of today’s Divine Liturgy. SPECIAL HYMNS SUNG DURING DIVINE LITURGY 1./2./4./10./11.