District Thatta (Sindh)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Improving Decision-Making Systems for Decentralized Primary Education Delivery in Pakistan

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore Pardee RAND Graduate School View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the Pardee RAND Graduate School (PRGS) dissertation series. PRGS dissertations are produced by graduate fellows of the Pardee RAND Graduate School, the world’s leading producer of Ph.D.’s in policy analysis. The dissertation has been supervised, reviewed, and approved by the graduate fellow’s faculty committee. Improving Decision-making Systems for Decentralized Primary Education Delivery in Pakistan Mohammed Rehan Malik This document was submitted as a dissertation in July 2007 in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the doctoral degree in public policy analysis at the Pardee RAND Graduate School. -

CWS-P/A Has Empowered Women in Thatta District with Skills, Basic Education, and Knowledge on Staying Safe

CWS-P/A has empowered women in Thatta District with skills, basic education, and knowledge on staying safe. Photo by Shahzad A. Fayyaz. FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION ONLY January - April 2014 Newsletter Volume 13, Issue 33 2014 Dear Readers, We welcome you to read CWS-P/A’s first newsletter for 2014. This January to April edition contains news about projects which continually impact the lives of communities in Pakistan and Afghanistan in positive ways. The projects include interventions in health and livelihoods for families in the districts of Kohat, Mansehra, Haripur, and Thatta in Pakistan. In Afghanistan, CWS-P/A continues to strengthen educational opportunities, especially for girls, by increasing awareness among parents and community members and by building the capacity of teachers. The newsletter also highlights work in Afghanistan toward improving health, especially for women and children. Additionally, read about the organization’s work for minorities and in raising awareness on the issues they face. There is further news about CWS-P/A’s work in promoting quality and accountability. This edition’s Hot Topic is about contingency planning for humanitarian organizations. We express our gratitude to you for taking the time to read our newsletter. You may send feedback and In This Edition suggestions to [email protected] The CWS - P/A team Quality and Accountability In this Edition 02 for Project Cycle Management Suggested Reading 02 – A Pocket Booklet for Field Mission Statement 02 Practitioners News from CWS-P/A 03 Vocational Training Inspires Young Afghan Men and Women 10 Implementing Education with Sports and Play 12 Guldasta’s Story: Helping Women Regain Good Health 14 Words of Wisdom 16 Hot Topic 16 Suggested Reading By: Sylvie Robert and Astrid de Valon Table of Contents Table The first edition of the Quality and Accountability for Project Cycle Management booklet is a CWS–P/A as an ecumenical organization user-friendly guide to the various quality will struggle for a community based and accountability tools and standards. -

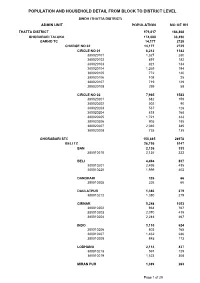

Population and Household Detail from Block to District Level

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH THATTA DISTRICT 979,817 184,868 GHORABARI TALUKA 174,088 33,450 GARHO TC 14,177 2725 CHARGE NO 02 14,177 2725 CIRCLE NO 01 6,212 1142 380020101 1,327 280 380020102 897 182 380020103 821 134 380020104 1,269 194 380020105 772 140 380020106 108 25 380020107 719 129 380020108 299 58 CIRCLE NO 02 7,965 1583 380020201 682 159 380020202 502 90 380020203 537 128 380020204 818 168 380020205 1,721 333 380020206 905 185 380020207 2,065 385 380020208 735 135 GHORABARI STC 150,885 28978 BELI TC 26,756 5147 BAN 2,136 333 380010210 2,136 333 BELI 4,494 837 380010201 2,495 435 380010220 1,999 402 DANDHARI 326 66 380010205 326 66 DAULATPUR 1,380 279 380010212 1,380 279 GIRNAR 5,248 1053 380010202 934 167 380010203 2,070 419 380010204 2,244 467 INDO 3,110 624 380010206 803 165 380010207 1,462 286 380010208 845 173 LODHANO 2,114 437 380010218 591 129 380010219 1,523 308 MIRAN PUR 1,389 263 Page 1 of 29 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (THATTA DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 380010213 529 102 380010214 860 161 SHAHPUR 3,016 548 380010215 1,300 243 380010216 901 160 380010221 815 145 SUKHPUR 1,453 275 380010209 1,453 275 TAKRO 668 136 380010217 668 136 VIKAR 1,422 296 380010211 1,422 296 GARHO TC 22,344 4350 ADANO 400 80 380010113 400 80 GAMBWAH 440 58 380010110 440 58 GUBA WEST 509 105 380010126 509 105 JARYOON 366 107 380010109 366 107 JHORE PATAR 6,123 1143 380010118 504 98 380010119 1,222 231 380010120 -

Government of Sindh Road Resources Management (RRM) Froject Project No

FINAL REPORT Mid-Term Evaluation /' " / " kku / Kondioro k I;sDDHH1 (Koo1,, * Nowbshoh On$ Hyderobcd Bulei Pt.ochi 7 godin Government of Sindh Road Resources Management (RRM) Froject Project No. 391-0480 Prepared for the United States Agency for International Development Islamabad, Pakistan IOC PDC-0249-1-00-0019-00 * Delivery Order No. 23 prepared by DE LEUWx CATHER INTERNATIONAL LIMITED May 26, 1993 Table of Contents Section Pafle Title Page i Table of Contents ii List of Tables and Figures iv List of Abbieviations, Acronyms vi Basic Project Identification Data Sheet ix AID Evaluation Summary x Chapter 1 - Introduction 1-1 Chapter 2 - Background 2-1 Chapter 3 - Road Maintenance 3-1 Chapter 4 - Road Rehabilitation 4-1 Chapter 5 - Training Programs 5-1 Chapter 6 - District Revenue Sources 6-1 Appendices: - A. Work Plan for Mid-term Evaluation A-1 - B. Principal Officers Interviewed B-1 - C. Bibliography of Documents C-1 - D. Comparison of Resources and Outputs for Maintenance of District Roads in Sindh D-1 - E. Paved Road System Inventories: 6/89 & 4/93 E-1 - F. Cost Benefit Evaluations - Districts F-1 - ii Appendices (cont'd.): - G. "RRM" Road Rehabilitation Projects in SINDH PROVINCE: F.Y.'s 1989-90; 1991-92; 1992-93 G-1 - H. Proposed Training Schedule for Initial Phase of CCSC Contract (1989 - 1991) H-1 - 1. Maintenance Manual for District Roads in Sindh - (Revised) August 1992 I-1 - J. Model Maintenance Contract for District Roads in Sindh - August 1992 J-1 - K. Sindh Local Government and Rural Development Academy (SLGRDA) - Tandojam K-1 - L. -

District Profile Thatta

Neighboring Risk District Thatta Hazard, Vulnerability and Development Profile Neighboring Risk: An Alternative Approach to Understanding and Responding to Hazards and Vulnerability in Pakistan Published by: Rural Development Policy Institute (RDPI), Islamabad Copyright © 2010 Rural Development Policy Institute Office 6, Ramzan Plaza, G 9 Markaz, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: +92 51 285 6623, +92 51 285 4523 Fax: +92 51 285 4783 URL: www.rdpi.org.pk This publication is produced by RDPI with financial support from Plan Pakistan. Citation is encouraged. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non- commercial purpose is authorized without prior written permission from RDPI, provided the source is fully acknowledged.Production, resale or other commercial purposes are prohibited without prior written permission from RDPI, Islamabad, Pakistan. The contents of this document or the opinions expressed may not necessarily constitute an endorsement by Plan Pakistan. Citation: Neighboring Risk, RDPI, Islamabad, 2010 ISBN: 978-969-9041-02-0 Authored by: Abdul Shakoor Sindhu Research Team: Beenish Kulsoom, Saqib Shehzad, Tariq Chishti, Tailal Masood, Gulzar Habib, Abida Nasren, Qaswer Abbas Text Editing: Masood Alam Cover & Layout Design: Abdul Shakoor Sindhu Photos: Abdul Shakoor Sindhu, Saqib Shehzad, Beenish Kulsoom, Tariq Chishti, Asif Khattak Printed by: Pictorial Printers (Pvt) Ltd. 21, I & T Centre, G-6/1, Aabpara, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: +92 51 2822692 Available from: Rural Development Policy Institute Office 6, Ramzan Plaza, G-9 Markaz, Islamabad, Pakistan Phone: +92 51 285 6623, +92 51 285 4523 Fax: +92 51 285 4783 Website: www.rdpi.org.pk Be a part of it Rural Development Policy Institute (RDPI) is a civil 'Plan' is an international organization working in initiative aimed to stimulate public dialogue on policies, Pakistan since 1997. -

Flood Assessment of District Thatta

Flood Assessment of District Thatta Brief history and Introduction of Thatta Thatta is the historically rich and civilized city of Sindh. It is tail of river Indus, near to delta. As the river Indus has flooded the badly to entire Sindh which has ended at Thatta district, but its end is going so severe and serious. The dykes at Thatta were extremely vulnerable and feeble that they could not bear the increasing flow of water that touched the strength of 9,50,000 cusecs water. As soon as water touched the dykes of Thatta, water over flew the both banks of Indus River. The District Thatta derives its name after it’s headquarter town which is one of the oldest town and had been capital of Sindh. The District lies at 23-42, to 25-26, North latitude and 67-05, to 68-46 East latitude. It is bounded on the north by District Jamshoro, on the East Tando Muhammad Khan and Badin District on the South (Run of Kachh) and Arabian Sea, on the West is bounded by Karachi District. The total Area of the District is 17,355 Square Kilometers whereas the population of the district is around 1.20 Million. District Thatta is administratively managed by 9 Talukas, 55 Union Councils, 75 Tappas and 656 Dehs. River Indus passes through Thatta by dividing the District in such a way that five Talukas viz: Thatta, Mirpur Sakro, Ghorabari, Ketibunder & Kharochan (Approximately half) i.e, Mirpur Bathoro, Sujawal, Jati and Shahbunder are on the left bank, fall on the Right Bank and four Talukas on left Bank of the River Indus. -

Spatio-Temporal Changes in Economic Development: a Case Study of Sindh Province

Karachi University Journal of Science, 2012, 40, 25-30 25 Spatio-temporal Changes in Economic Development: A case study of Sindh Province Razzaq Ahmed1 and Khalida Mahmood2,* 1Department of Geography, Federal Urdu University of Arts Sciences and Technology, Karachi and 2Department of Geography, University of Karachi, Karachi, Pakistan Abstract: This study has been conducted at a time when Pakistan is passing through an important phase of economic development and reconstruction. Devolution has become an important aspect of the planning and decision making process. Decentralization is being emphasized by both public and private sectors of development. In such a situation, present study focuses on the evaluation of the past and present patterns of the levels of development in various districts of the province of Sindh. This research will certainly contribute to an understanding of the development patterns in the province. Key Words: composite index, level of development, ranking, socio-economic inequality, Z-score. INTRODUCTION METHODOLOGICAL FRAMEWORK Sindh has experienced considerable urbanization since To measure the level of development of the districts of independence in 1947, which has resulted in the explosive Sindh, twelve variables have been employed on thirteen 1 growth of urban centers like Karachi, Hyderabad and districts of 1981 and sixteen districts of 1998 . These Sukkur. The growth of Karachi in particular has been variables are non-agricultural labor force, employment in phenomenal. Its exceptional growth as compared to the rest manufacturing, immigration, own farm, cultivated area, of Sindh, which is basically rural in nature, brings out unique population potential, manufacturing value added (rupees per patterns of socio-economic inequality. -

The People of Karachi Demographic Characteristics

MONOGRAPHS IN THE ECONOMICS OF DEVELOPMENT No. 13 The People of Karachi Demographic Characteristics SULTAN S. HASHMI January 1965 PAKISTAN INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPMENT ECONOMICS Old Sind Assembly Building Bunder Road, Karachi (Pakistan) Price Rs. 5.00 PAKISTAN INSTITUTE OF DEVELOPME :ONOMICS Old Sind Assembly Building Bunder Road, Karachi-1 (Pakistan) The Institute carries out basic research studies on the economic problems of development in Pakistan and other Asian countries. It also provides training in economic analysis and research methodology for the professional members of its staff and for members of other organization concerned with development problems. Executive Board Mr. Said Hasan, H.Q.A. (Chairman) Mr. S. A. F. M. A. Sobhan Mr. G. S. Kehar, S.Q.A. (Member) (Member) Mr. M. L. Qureshi, S.Q.A. Mr. M. Raschid (Member) (Member) Mr. A. Rashid Ibrahim Mr. S. M. Sulaiman (Member-Treasurer) (Member) Professor A. F. A. Hussain Dr. Mahbubul Haq (Member) (Member) Mian Nazir Ahmad, T.Q.A. (Secretary) Director: Professor Nurul Islam Senior Research Adviser: Dr. Bruce Glassburner Research Advisers: Dr. W. Eric Gustafson; Dr. Ronald Soligo; Dr. Stephen R. Lewis, Jr.; Dr. Warren C. Robinson; Mr. William Seltzer. Senior Fellows: Dr. S. A. Abbas; Dr. M. Baqai; Dr. Mahbubul Haq; Professor T. Haq; Professor A. F. A. Hussain; Dr. R. H. Khandkar; Dr. Taufique Khan; Professor M. Rashid. Advisory Board Professor Max F. Millikan, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Professor Gunnar Myrdal, University of Stockholm. Professor E. A. G. Robinson, Cambridge University. MONOGRAPHS IN THE ECONOMICS OF DEVELOPMENT No. 13 The People of Karachi Demographic Characteristics SULTANS. -

(RNA) Monsoon Rains

Rapid Need Assessment Report (RNA) Monsoon Rains Thatta, Sujawal and Hyderabad th th 24 – 27 August 2020 Thatta Sujjawal Hyderabad Prepared by: Health And Nutrition Development Society (HANDS) Address: Plot #158, Off M9 (Karachi – Hyderabad) Motorway, Gadap Road, Karachi, Pakistan, Ph: (0092-21) 32120400-9 , +92-3461117771 Web: www.hands.org.pk Email: [email protected] Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Background ................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2. Objectives .................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3. Methodology ................................................................................................................................ 4 1.4. Limitations ................................................................................................................................... 4 1.5. Summary of Findings ................................................................................................................. 4 1.6. Sectoral Need Priority Ranking................................................................................................. 6 2. Key Findings District Thatta .............................................................................................................. -

Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition Program

SFG3075 REV Public Disclosure Authorized Pakistan Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition Program Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning, Planning & Public Disclosure Authorized Development Department, Government of Sindh Final Report December 2016 Public Disclosure Authorized Environmental and Social Management Framework Final Report Executive Summary Local Government and Housing Town Planning Department, GOS and Agriculture Department GOS with grant assistance from DFID funded multi donor trust fund for Nutrition in Pakistan are planning to undertake Multi-Sectoral Action for Nutrition (MSAN) Project. ESMF Consultant1 has been commissioned by Directorate of Urban Policy & Strategic Planning to fulfil World Bank Operational Policies and to prepare “Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) for MSAN Project” at its inception stage via assessing the project’s environmental and social viability through various environmental components like air, water, noise, land, ecology along with the parameters of human interest and mitigating adverse impacts along with chalking out of guidelines, SOPs, procedure for detailed EA during project execution. The project has two components under Inter Sectoral Nutrition Strategy of Sindh (INSS), i) the sanitation component of the project aligns with the Government of Sindh’s sanitation intervention known as Saaf Suthro Sindh (SSS) in 13 districts in the province and aims to increase the number of ODF villages through certification while ii) the agriculture for nutrition (A4N) component includes pilot targeting beneficiaries for household production and consumption of healthier foods through increased household food production in 20 Union Councils of 4 districts. Saaf Suthro Sindh (SSS) This component of the project will be sponsored by Local Government and Housing Town Planning Department, Sindh and executed by Local Government Department (LGD) through NGOs working for the Inter-sectoral Nutrition Support Program. -

Indus for All Programme, WWF Pakistan Response to Floods in Thatta September 1, 2010

Indus for All Programme, WWF Pakistan Response to Floods in Thatta September 1, 2010 Water Tanks Distribution to the IDPs on Ghulamullah Road, Thatta 1. Background WWF-Pakistan, in collaboration with other stakeholders including the Planning and Development Department, Government of Sindh, is implementing a 5-year Indus for All Programme in the province of Sindh. The Programme is the implementation phase of a 50-year vision of the Indus Ecoregion Conservation Programme. The Indus ecoregion partially or fully covers several districts of the province, while Indus for All Programme is being implemented in four priority ecosystems in three districts, Thatta, Shaheed Benazirabad and Sanghar. The Programme has two site offices (Keenjhar and Keti Bunder) in Thatta District, which is badly heavily affected by recent floods. Following is the brief on the response made by Indus for All Programme in Thatta District. 2. Network formation District Thatta is one of the districts of Sindh province where a large number of local, provincial, national as well international non-governmental organizations (NGOs) are working under their mandate and implementing variety of projects. Obviously they are contributing for the development and upliftment of most deprived people of the district. It was felt that all NGOs are working within their mandate but without coordination due to that the impression in the Govt. bodies is not so positive regarding their service delivery in the District. To ensure the consolidated effort and to avoid any sort of duplication as well as waste of resources it was shared with all the active NGOs of the District to work on one platform to show some tangible results and have good gestures with District Govt. -

Assessing the Impact of Devolution of Healthcare and Education in Pakistan

ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF DEVOLUTION ON HEALTHCARE AND EDUCATION IN PAKISTAN Prepared by Prepared for Ritu Nayyar-Stone Robert Ebel Sonia Ignatova Khalid Rashid with Pakistan Devolution Support Project Harry Hatry United States Agency for International Development George Peterson Contract No. DFD-I-00-05-00129-00, Order No. 01 February 2006 UI Project 07862-001 THE URBAN INSTITUTE 2100 M Street, NW Washington, DC 20037 +1 (202) 833-7200 www.urban.org ASSESSMENT REPORT PAKISTAN DEVOLUTION SUPPORT PROJECT TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................................................2 I.A The Background of Devolution .................................................................................................................2 I.B The Structure of Government...................................................................................................................2 II. PROGRESS AND CHALLENGES TO EFFECTIVE DEMOCRATIC DEVOLUTION.............................................8 II.A Effective and Cost-Efficient Service Delivery............................................................................................8 II.A.1 Health.........................................................................................................................................8 II.A.2 Education .................................................................................................................................17 II.A.3 Water Supply