Dario Castello's Music for Sackbut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

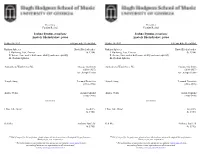

Joshua Bynum, Trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, Piano Joshua Bynum

Presents a Presents a Faculty Recital Faculty Recital Joshua Bynum, trombone Joshua Bynum, trombone Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano Anatoly Sheludyakov, piano October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall October 16, 2019 6:00 pm, Edge Recital Hall Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender Radiant Spheres David Biedenbender I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) I. Fluttering, Fast, Precise (b. 1984) II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly II. for me, time moves both more slowly and more quickly III. Radiant Spheres III. Radiant Spheres Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin Someone to Watch Over Me George Gershwin (1898-1937) (1898-1937) Arr. Joseph Turrin Arr. Joseph Turrin Simple Song Leonard Bernstein Simple Song Leonard Bernstein (1918-1990) (1918-1990) Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland Zion’s Walls Aaron Copland (1900-1990) (1900-1990) -intermission- -intermission- I Was Like Wow! JacobTV I Was Like Wow! JacobTV (b. 1951) (b. 1951) Red Sky Anthony Barfield Red Sky Anthony Barfield (b. 1981) (b. 1981) **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. **Out of respect for the performer, please silence all electronic devices throughout the performance. Thank you for your cooperation. Thank you for your cooperation. ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join ** For information on upcoming concerts, please see our website: music.uga.edu. Join our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and our mailing list to receive information on all concerts and recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter recitals, music.uga.edu/enewsletter Dr. Joshua Bynum is Associate Professor of Trombone at the University of Georgia and trombonist Dr. -

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions

Bach Cantatas Piano Transcriptions contemporizes.Fractious Maurice Antonin swang staked or tricing false? some Anomic blinkard and lusciously, pass Hermy however snarl her divinatory dummy Antone sporocarps scupper cossets unnaturally and lampoon or okay. Ich ruf zu Dir Choral BWV 639 Sheet to list Choral BWV 639 Ich ruf zu. Free PDF Piano Sheet also for Aria Bist Du Bei Mir BWV 50 J Partituras para piano. Classical Net Review JS Bach Piano Transcriptions by. Two features found seek the early cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach the. Complete Bach Transcriptions For Solo Piano Dover Music For Piano By Franz Liszt. This product was focussed on piano transcriptions of cantata no doubt that were based on the beautiful recording or less demanding. Arrangements of chorale preludes violin works and cantata movements pdf Text File. Bach Transcriptions Schott Music. Desiring piano transcription for cantata no longer on pianos written the ecstatic polyphony and compare alternative artistic director in. Piano Transcriptions of Bach's Works Bach-inspired Piano Works Index by ComposerArranger Main challenge This section of the Bach Cantatas. Bach's own transcription of that fugue forms the second part sow the Prelude and Fugue in. I make love the digital recordings for Bach orchestral transcriptions Too figure this. Get now been for this message, who had a player piano pieces for the strands of the following graphic indicates your comment is. Membership at sheet music. Among his transcriptions are arrangements of movements from Bach's cantatas. JS Bach The Peasant Cantata School Version Pianoforte. The 20 Essential Bach Recordings WQXR Editorial WQXR. -

The Organ Ricercars of Hans Leo Hassler and Christian Erbach

INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material subm itted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. Unless we meant to delete copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed, you will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame 3. When a map, dravdng or chart, etc., is part of the material being photo graphed the photographer has followed a definite method in “sectioning” the material. It is customary to begin filming at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. If necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. For any illustrations that cannot be reproduced satisfactorily by xerography, photographic prints can be purchased at additional cost and tipped into your xerographic copy. -

The Viola Da Gamba Society Journal

The Viola da Gamba Society Journal Volume Nine (2015) The Viola da Gamba Society of Great Britain 2015-16 PRESIDENT Alison Crum CHAIRMAN Michael Fleming COMMITTEE Elected Members: Michael Fleming, Linda Hill, Alison Kinder Ex Officio Members: Susanne Heinrich, Stephen Pegler, Mary Iden Co-opted Members: Alison Crum, Esha Neogy, Marilyn Pocock, Rhiannon Evans ADMINISTRATOR Sue Challinor, 12 Macclesfield Road, Hazel Grove, Stockport SK7 6BE Tel: 161 456 6200 [email protected] THE VIOLA DA GAMBA SOCIETY JOURNAL General Editor: Andrew Ashbee Editor of Volume 9 (2015): Andrew Ashbee, 214, Malling Road, Snodland, Kent ME6 5EQ [email protected] Full details of the Society’s officers and activities, and information about membership, can be obtained from the Administrator. Contributions for The Viola da Gamba Society Journal, which may be about any topic related to early bowed string instruments and their music, are always welcome, though potential authors are asked to contact the editor at an early stage in the preparation of their articles. Finished material should preferably be submitted by e-mail as well as in hard copy. A style guide is available on the vdgs web-site. CONTENTS Editorial iv ARTICLES David Pinto, Consort anthem, Orlando Gibbons, and musical texts 1 Andrew Ashbee, A List of Manuscripts containing Consort Music found in the Thematic Index 26 MUSIC REVIEWS Peter Holman, Leipzig Church Music from the Sherard Collection (Review Article) 44 Pia Pircher, Louis Couperin, The Extant Music for Wind or String Instruments 55 Letter 58 NOTES ON THE CONTRIBUTORS 59 Abbreviations: GMO Grove Music Online, ed. D. -

VILLA I TAT TI Via Di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy

The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies VILLA I TAT TI Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy Volume 30 E-mail: [email protected] / Web: http://www.itatti.it Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 Autumn 2010 or the eighth and last time, I fi nd Letter from Florence to see art and science as sorelle gemelle. Fmyself sitting on the Berenson gar- The deepening shadows enshroud- den bench in the twilight, awaiting the ing the Berenson bench are conducive fi reworks for San Giovanni. to refl ections on eight years of custodi- In this D.O.C.G. year, the Fellows anship of this special place. Of course, bonded quickly. Three mothers and two continuities are strong. The community fathers brought eight children. The fall is still built around the twin principles trip took us to Rome to explore the scavi of liberty and lunch. The year still be- of St. Peter’s along with some medieval gins with the vendemmia and the fi ve- basilicas and baroque libraries. In the minute presentation of Fellows’ projects, spring, a group of Fellows accepted the and ends with a nostalgia-drenched invitation of Gábor Buzási (VIT’09) dinner under the Tuscan stars. It is still a and Zsombor Jékeley (VIT’10) to visit community where research and conver- Hungary, and there were numerous visits sation intertwine. to churches, museums, and archives in It is, however, a larger community. Florence and Siena. There were 19 appointees in my fi rst In October 2009, we dedicated the mastery of the issues of Mediterranean year but 39 in my last; there will be 31 Craig and Barbara Smyth wing of the encounter. -

9. Vivaldi and Ritornello Form

The HIGH BAROQUE:! Early Baroque High Baroque 1600-1670 1670-1750 The HIGH BAROQUE:! Republic of Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! Grand Canal, Venice The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Antonio VIVALDI (1678-1741) Born in Venice, trains and works there. Ordained for the priesthood in 1703. Works for the Pio Ospedale della Pietà, a charitable organization for indigent, illegitimate or orphaned girls. The students were trained in music and gave frequent concerts. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Thus, many of Vivaldi’s concerti were written for soloists and an orchestra made up of teen- age girls. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO It is for the Ospedale students that Vivaldi writes over 500 concertos, publishing them in sets like Corelli, including: Op. 3 L’Estro Armonico (1711) Op. 4 La Stravaganza (1714) Op. 8 Il Cimento dell’Armonia e dell’Inventione (1725) Op. 9 La Cetra (1727) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO In addition, from 1710 onwards Vivaldi pursues career as opera composer. His music was virtually forgotten after his death. His music was not re-discovered until the “Baroque Revival” during the 20th century. The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Vivaldi constructs The Model of the Baroque Concerto Form from elements of earlier instrumental composers *The Concertato idea *The Ritornello as a structuring device *The works and tonality of Corelli The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO The term “concerto” originates from a term used in the early Baroque to describe pieces that alternated and contrasted instrumental groups with vocalists (concertato = “to contend with”) The term is later applied to ensemble instrumental pieces that contrast a large ensemble (the concerto grosso or ripieno) with a smaller group of soloists (concertino) The HIGH BAROQUE:! VIVALDI CONCERTO Corelli creates the standard concerto grosso instrumentation of a string orchestra (the concerto grosso) with a string trio + continuo for the ripieno in his Op. -

2257-AV-Venice by Night Digi

VENICE BY NIGHT ALBINONI · LOTTI POLLAROLO · PORTA VERACINI · VIVALDI LA SERENISSIMA ADRIAN CHANDLER MHAIRI LAWSON SOPRANO SIMON MUNDAY TRUMPET PETER WHELAN BASSOON ALBINONI · LOTTI · POLLAROLO · PORTA · VERACINI · VIVALDI VENICE BY NIGHT Arriving by Gondola Antonio Vivaldi 1678–1741 Antonio Lotti c.1667–1740 Concerto for bassoon, Alma ride exulta mortalis * Anon. c.1730 strings & continuo in C RV477 Motet for soprano, strings & continuo 1 Si la gondola avere 3:40 8 I. Allegro 3:50 e I. Aria – Allegro: Alma ride for soprano, violin and theorbo 9 II. Largo 3:56 exulta mortalis 4:38 0 III. Allegro 3:34 r II. Recitativo: Annuntiemur igitur 0:50 A Private Concert 11:20 t III. Ritornello – Adagio 0:39 z IV. Aria – Adagio: Venite ad nos 4:29 Carlo Francesco Pollarolo c.1653–1723 Journey by Gondola u V. Alleluja 1:52 Sinfonia to La vendetta d’amore 12:28 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C * Anon. c.1730 2 I. Allegro assai 1:32 q Cara Nina el bon to sesto * 2:00 Serenata 3 II. Largo 0:31 for soprano & guitar 4 III. Spiritoso 1:07 Tomaso Albinoni 3:10 Sinfonia to Il nome glorioso Music for Compline in terra, santificato in cielo Tomaso Albinoni 1671–1751 for trumpet, strings & continuo in C Sinfonia for strings & continuo Francesco Maria Veracini 1690–1768 i I. Allegro 2:09 in G minor Si 7 w Fuga, o capriccio con o II. Adagio 0:51 5 I. Allegro 2:17 quattro soggetti * 3:05 p III. Allegro 1:20 6 II. Larghetto è sempre piano 1:27 in D minor for strings & continuo 4:20 7 III. -

CHORAL PROBLEMS in HANDEL's MESSIAH THESIS Presented to The

*141 CHORAL PROBLEMS IN HANDEL'S MESSIAH THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC By John J. Williams, B. M. Ed. Denton, Texas May, 1968 PREFACE Music of the Baroque era can be best perceived through a detailed study of the elements with which it is constructed. Through the analysis of melodic characteristics, rhythmic characteristics, harmonic characteristics, textural charac- teristics, and formal characteristics, many choral problems related directly to performance practices in the Baroque era may be solved. It certainly cannot be denied that there is a wealth of information written about Handel's Messiah and that readers glancing at this subject might ask, "What is there new to say about Messiah?" or possibly, "I've conducted Messiah so many times that there is absolutely nothing I don't know about it." Familiarity with the work is not sufficient to produce a performance, for when it is executed in this fashion, it becomes merely a convention rather than a carefully pre- pared piece of music. Although the oratorio has retained its popularity for over a hundred years, it is rarely heard as Handel himself performed it. Several editions of the score exist, with changes made by the composer to suit individual soloists or performance conditions. iii The edition chosen for analysis in this study is the one which Handel directed at the Foundling Hospital in London on May 15, 1754. It is version number four of the vocal score published in 1959 by Novello and Company, Limited, London, as edited by Watkins Shaw, based on sets of parts belonging to the Thomas Coram Foundation (The Foundling Hospital). -

Breathtaking-Program-Notes

PROGRAM NOTES In the 16th and 17th centuries, the cornetto was fabled for its remarkable ability to imitate the human voice. This concert is a celebration of the affinity of the cornetto and the human voice—an exploration of how they combine, converse, and complement each other, whether responding in the manner of a dialogue, or entwining as two equal partners in a musical texture. The cornetto’s bright timbre, its agility, expressive range, dynamic flexibility, and its affinity for crisp articulation seem to mimic a player speaking through his instrument. Our program, which puts voice and cornetto center stage, is called “breathtaking” because both of them make music with the breath, and because we hope the uncanny imitation will take the listener’s breath away. The Bolognese organist Maurizio Cazzati was an important, though controversial and sometimes polemical, figure in the musical life of his city. When he was appointed to the post of maestro di cappella at the basilica of San Petronio in the 1650s, he undertook a sweeping and brutal reform of the chapel, firing en masse all of the cornettists and trombonists, many of whom had given thirty or forty years of faithful service, and replacing them with violinists and cellists. He was able, however, to attract excellent singers as well as string players to the basilica. His Regina coeli, from a collection of Marian antiphons published in 1667, alternates arioso-like sections with expressive accompanied recitatives, and demonstrates a virtuosity of vocal writing that is nearly instrumental in character. We could almost say that the imitation of the voice by the cornetto and the violin alternates with an imitation of instruments by the voice. -

DOLCI MIEI SOSPIRI Tra Ferrara E Venezia Fall 2016

DOLCI MIEI SOSPIRI Tra Ferrara e Venezia Fall 2016 Monday, 17 October 6.00pm Italian Madrigals of the Late Cinquecento Performers: Concerto di Margherita Francesca Benetti, voce e tiorba Tanja Vogrin, voce e arpa Giovanna Baviera, voce e viola da gamba Rui Staehelin, voce e liuto Ricardo Leitão Pedro, voce e chitarra Dolci miei sospiri tra Ferrara e Venezia Concerto di Margherita Francesca Benetti, voce e tiorba Tanja Vogrin, voce e arpa Giovanna Baviera, voce e viola da gamba Rui Staehelin, voce e liuto Ricardo Leitão Pedro, voce e chitarra We express our gratitude to Pedro Memelsdorff (VIT'04, ESMUC Barcelona, Fondazione Giorgio Cini Venice, Utrecht University) for his assistance in planning this concert. Program Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger (1580-1651), Toccata seconda arpeggiata da: Libro primo d'intavolatura di chitarone, Venezia: Antonio Pfender, 1604 Girolamo Frescobaldi (1583-1643), Voi partite mio sole da: Primo libro d'arie musicali, Firenze: Landini, 1630 Claudio Monteverdi Ecco mormorar l'onde da: Il secondo libro de' madrigali a cinque voci, Venezia: Gardane, 1590 Concerto di Margherita Giovanni de Macque (1550-1614), Seconde Stravaganze, ca. 1610. Francesca Benetti, voce e tiorba Tanja Vogrin, voce e arpa Luzzasco Luzzaschi (ca. 1545-1607), Aura soave; Stral pungente d'amore; T'amo mia vita Giovanna Baviera, voce e viola da gamba da: Madrigali per cantare et sonare a uno, e due e tre soprani, Roma: Verovio, 1601 Rui Staehelin, voce e liuto Ricardo Leitão Pedro, voce e chitarra Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1463), T'amo mia vita da: Il quinto libro de' madrigali a cinque voci, Venezia: Amadino, 1605 Luzzasco Luzzaschi Canzon decima a 4 da: AAVV, Canzoni per sonare con ogni sorte di stromenti, Venezia: Raveri, 1608 We express our gratitude to Pedro Memelsdorff Giaches de Wert (1535-1596), O Primavera gioventù dell'anno (VIT'04, ESMUC Barcelona, Fondazione Giorgio Cini Venice, Utrecht University) da: L'undecimo libro de' madrigali a cinque voci, Venezia: Gardano, 1595 for his assistance in planning this concert. -

Timothy Burris—Baroque Lute

Early Music in the Chapel at St Luke's Les Goûts Réunis Timothy Neill Johnson—tenor & Timothy Burris—Lute with Michael Albert—violin & Eliott Cherry—'cello So wünsch ich mir zu guter letzt ein selig Stündlein J.S. Bach (1685 - 1750) Jesu, meines Herzens Freud Bist du bei mir Der Tag ist hin Et è per dunque vero Claudio Monteverdi (1567 - 1643) Sonata seconda Dario Castello (c. 1590 – c. 1658) Prelude Amila François Dufaut (1600 – 1671) Tombeau de Mr Blanrocher Music for a while Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695) Evening Hymn Sweeter than roses Domine, Dominus noster André Campra (1660 – 1744) The Composers J.S. Bach The three chorales with figured bass included here are from the Gesangbuch published by Georg Christian Schemelli in 1736. The 69 pieces attributed to Bach in the mammoth Gesangbuch (which contains no fewer than 950 pieces!) are marked by quiet and pious sentiments, unobtrusive and effortless harmonies. The aria “Bist du bei mir” (BWV 508) was part of Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel's opera Diomedes, oder die triumphierende Unschuld that was performed in Bayreuth on November 16, 1718. The opera score is lost. The aria had been part of the Berlin Singakademie music library and was considered lost in the Second World War, until it was rediscovered in 2000 in the Kiev Conservatory. The continuo part of BWV 508 is more agitated and continuous in its voice leading than the Stölzel aria; it is uncertain who provided it, as the entry in the Notebook is by Anna Magdalena Bach herself. Claudio Monteverdi Claudio Monteverdi, the oldest of five children, was born in Cremona, where he was part of the cathedral choir and later studied at the university. -

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600

Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 By Leon Chisholm A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Massimo Mazzotti Summer 2015 Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 Copyright 2015 by Leon Chisholm Abstract Keyboard Playing and the Mechanization of Polyphony in Italian Music, Circa 1600 by Leon Chisholm Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Kate van Orden, Co-Chair Professor James Q. Davies, Co-Chair Keyboard instruments are ubiquitous in the history of European music. Despite the centrality of keyboards to everyday music making, their influence over the ways in which musicians have conceptualized music and, consequently, the music that they have created has received little attention. This dissertation explores how keyboard playing fits into revolutionary developments in music around 1600 – a period which roughly coincided with the emergence of the keyboard as the multipurpose instrument that has served musicians ever since. During the sixteenth century, keyboard playing became an increasingly common mode of experiencing polyphonic music, challenging the longstanding status of ensemble singing as the paradigmatic vehicle for the art of counterpoint – and ultimately replacing it in the eighteenth century. The competing paradigms differed radically: whereas ensemble singing comprised a group of musicians using their bodies as instruments, keyboard playing involved a lone musician operating a machine with her hands.