Endangered Nilgiri Tahr of the Anamalai Tiger Reserve

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi

by Keshav Ravi by Keshav Ravi Preface About the Author In the whole world, there are more than 30,000 species Keshav Ravi is a caring and compassionate third grader threatened with extinction today. One prominent way to who has been fascinated by nature throughout his raise awareness as to the plight of these animals is, of childhood. Keshav is a prolific reader and writer of course, education. nonfiction and is always eager to share what he has learned with others. I have always been interested in wildlife, from extinct dinosaurs to the lemurs of Madagascar. At my ninth Outside of his family, Keshav is thrilled to have birthday, one personal writing project I had going was on the support of invested animal advocates, such as endangered wildlife, and I had chosen to focus on India, Carole Hyde and Leonor Delgado, at the Palo Alto the country where I had spent a few summers, away from Humane Society. my home in California. Keshav also wishes to thank Ernest P. Walker’s Just as I began to explore the International Union for encyclopedia (Walker et al. 1975) Mammals of the World Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List species for for inspiration and the many Indian wildlife scientists India, I realized quickly that the severity of threat to a and photographers whose efforts have made this variety of species was immense. It was humbling to then work possible. realize that I would have to narrow my focus further down to a subset of species—and that brought me to this book on the Endangered Mammals of India. -

Additions to the Bryophyte Flora of Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh, India 1

Additions to the Bryophyte flora of Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh, India 1 Additions to the Bryophyte flora of Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh, India 1 1 2 KRISHNA KUMAR RAWAT , VINAY SAHU , CHANDRA PRAKASH SINGH , PRAVEEN 3 KUMAR VERMA 1 CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute, Rana Pratap Marg, Lucknow -226001, India: [email protected], [email protected] 2AED/BPSG/EPSA, pace Applications Center, ISRO, Ahmadabad-380015, Gujarat, India: [email protected] 3Forest Research Institute, Dehradun, India: [email protected] Abstract: Rawat, K.K; Sahu, V.; Singh, C.P.; Verma, P.K. (2017): Additions to the Bryophyte flora of Tawang, Arunachal Pradesh, India. Frahmia 14:1-17. A total of 30 taxa of bryophytes are reported for the first time from Tawang district of Arunachal Pradesh, India, including 10 taxa as new to Arunachal Pradesh. 1. Introduction The district Tawang in Arunachal Pradesh, India, is located in extreme western corner of the state between 27º25’ & 27º45’N and 91º42’ & 92º39’ E covering an area of 2,172 km2 and is bordered with Tibet (China) to North, Bhutan to south-west and west Kameng district towards east. The bryo-floristic information of the area was unknown till Vohra and Kar (1996) published an account of 82 species of mosses from Arunachal Pradesh, including 12 from Tawang. Rawat and Verma (2014) published an account of 23 species of liverworts from Tawang. Recently Ellis et al (2016a, 2016b) reported two mosses viz., Splachnum sphaericum Hedw. and Polytrichastrum alpinum (Hedw.) G.L. Sm. from Tawang. The present paper provides additional information of 30 more bryophyte taxa from Tawang district of Arunachal Pradesh, making a sum of 67 bryophytes known so far from the district. -

Keralda/India) Ecology and Landscape in an Isolated Indian National Park Photos: Ian Lockwood

IAN LOCKWOOD Eravikolam and the High Range (Keralda/India) Ecology and Landscape in an Isolated Indian National Park Photos: Ian Lockwood The southern Indian state of Kerala has long been recognized for its remarkable human development indicators. It has the country’s highest literary rates, lowest infant mortality rates and highest life expectancy. With 819 people per km2 Kerala is also one of the densest populated states in India. It is thus surprising to find one of the India’s loneliest and least disturbed natural landscapes in the mountainous region of Kerala known as the High Range. Here a small 97 km2 National Park called Eraviku- lam gives a timeless sense of the Western Ghats before the widespread encroachment of plantation agriculture, hydro- electric schemes, mining and human settlements. he High Range is a part of the Western Ghats, a heterogeneous chain of mountains and hills that separate the moist Malabar and Konkan Coasts from the semi-arid interiors of the TDekhan plateau. They play a key role in direct- ing the South Western monsoon and providing water to the plateau and the coastal plains. Starting at the southern tip of India at Kanyakumari (Cape Comorin), the mountains rise abruptly from the sea and plains. The Western Ghats continue in a nearly unbroken 1,600 km mountainous spine and end at the Tapi River on the border between Maharashtra and Gujarat. Bio- logically rich, the Western Ghats are blessed with high rates of endemism. In recent years as a global alarm has sounded on declining biodiversity, the Western Ghats and Sri Lanka have been designated as one of 25 “Global Biodiversity Hotspots” by Conservation Inter- national. -

Bibliography on Tiger (Panthera Tigris L.)

Bibliography on Tiger (Panthera tigris L.) Global Tiger Forum Publication 2014 Copyright © Secretariat of Global Tiger Forum, 2014 Suggested Citation: Gopal R., Majumder A. and Yadav S.P. (Eds) (2014). Bibliography on Tiger (Panther tigris L.). Compiled and published by Global Tiger Forum, p 95. Cover Pic Vinit Arora Inside pictures taken by Vinit Arora, Samir K. Sinha, Aniruddha Majumder and S.P.Yadav CONTENTS Acknowledgements i Introduction to Bibliography on tiger 1 Literature collection and compilation process for bibliography on tiger 2-4 1) Ecology, Natural History and Taxonomy 5-23 2) Aspects of Conflicts 24-35 3) Monitoring (tiger, co-predator, prey and habitat) and Status 36-62 evaluation 4) Genetics, morphology, health and disease monitoring 63-75 5) Protection, Conservation, Policies and Bio-politics 76-95 Acknowledgements The “Bibliography on Tiger (Panthera tigris L.)” is an outcome of the literature database on tiger, brought out by the Global Tiger Forum (GTF). The GTF is thankful to all officials, scientists, conservationists from 13 Tiger Range Countries for their support. Special thanks are due to Dr Adam Barlow, Mr. Qamar Qureshi, Dr. Y.V. Jhala, Dr K. Sankar, Dr. S.P. Goyal, Dr John Seidensticker, Dr. Ullas Karanth, Dr. A.J.T Johnsingh, Dr. Sandeep Sharma, Ms. Grace Gabriel, Dr. Sonam Wangchuk, Mr Peter Puschel, Mr. Hazril Rafhan Abdul Halim, Mr Randeep Singh and Dr. Prajna Paramita Panda for sharing some important references on tiger. Mr P.K. Sen, Dr Jagdish Kiswan, Mr Vivek Menon, Mr Ravi Singh and Dr Sejal Vora and Mr Keshav Varma are duly acknowledged for their comments and suggestions. -

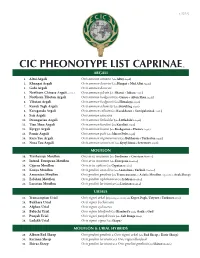

Cic Pheonotype List Caprinae©

v. 5.25.12 CIC PHEONOTYPE LIST CAPRINAE © ARGALI 1. Altai Argali Ovis ammon ammon (aka Altay Argali) 2. Khangai Argali Ovis ammon darwini (aka Hangai & Mid Altai Argali) 3. Gobi Argali Ovis ammon darwini 4. Northern Chinese Argali - extinct Ovis ammon jubata (aka Shansi & Jubata Argali) 5. Northern Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Gansu & Altun Shan Argali) 6. Tibetan Argali Ovis ammon hodgsonii (aka Himalaya Argali) 7. Kuruk Tagh Argali Ovis ammon adametzi (aka Kuruktag Argali) 8. Karaganda Argali Ovis ammon collium (aka Kazakhstan & Semipalatinsk Argali) 9. Sair Argali Ovis ammon sairensis 10. Dzungarian Argali Ovis ammon littledalei (aka Littledale’s Argali) 11. Tian Shan Argali Ovis ammon karelini (aka Karelini Argali) 12. Kyrgyz Argali Ovis ammon humei (aka Kashgarian & Hume’s Argali) 13. Pamir Argali Ovis ammon polii (aka Marco Polo Argali) 14. Kara Tau Argali Ovis ammon nigrimontana (aka Bukharan & Turkestan Argali) 15. Nura Tau Argali Ovis ammon severtzovi (aka Kyzyl Kum & Severtzov Argali) MOUFLON 16. Tyrrhenian Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka Sardinian & Corsican Mouflon) 17. Introd. European Mouflon Ovis aries musimon (aka European Mouflon) 18. Cyprus Mouflon Ovis aries ophion (aka Cyprian Mouflon) 19. Konya Mouflon Ovis gmelini anatolica (aka Anatolian & Turkish Mouflon) 20. Armenian Mouflon Ovis gmelini gmelinii (aka Transcaucasus or Asiatic Mouflon, regionally as Arak Sheep) 21. Esfahan Mouflon Ovis gmelini isphahanica (aka Isfahan Mouflon) 22. Larestan Mouflon Ovis gmelini laristanica (aka Laristan Mouflon) URIALS 23. Transcaspian Urial Ovis vignei arkal (Depending on locality aka Kopet Dagh, Ustyurt & Turkmen Urial) 24. Bukhara Urial Ovis vignei bocharensis 25. Afghan Urial Ovis vignei cycloceros 26. -

Kerala Tourism Goes Kindle with Destinations First State Tourism Board to Come out with Kindle Version of Destination Books

Press Release Kerala Tourism Goes Kindle With Destinations First state tourism board to come out with Kindle version of destination books Thiruvananthapuram, March 18: Online readers across the world will be able to get a close look at ‘God’s Own Country’ with Kerala Tourism taking to Kindle to provide a peep into its jaw dropping destinations. In a first of its kind by a state tourism board, five richly illustrated and informed books on Kerala’s major tourism destinations are now available on Kindle, the leading internet site and a favourite with e-readers with over a million books to choose from. The five books, explaining Kerala’s rich tapestry of history and its natural swathe of enchanting green, are Kerala and the Spice Routes, Silent Valley National Park, Periyar Tiger Reserve, Eravikulam National Park and Parambikulam Tiger Reserve. All the books are products of months of research and contain pictures taken by top professionals in nature and wild life photography. As a pioneer in using technology to provide information about Kerala and destinations, the state tourism department has taken a step further to appeal to the intellect and aesthetics of the discerning global traveller. The Kerala Tourism’s national and international award-winning website ( www.keralatourism.org ) is one of the leading tourism and travel websites in the world visited by millions of people. Kerala Tourism Facebook page, in English and German, is not only a medium for information about the state, but also a much-loved interaction site among the fans of ‘God’s Own Country’. Kerala Tourism is also the first tourism board in the country to webcast a classical dance performance of Theyyam live for the global audience. -

National Parks in India (State Wise)

National Parks in India (State Wise) Andaman and Nicobar Islands Rani Jhansi Marine National Park Campbell Bay National Park Galathea National Park Middle Button Island National Park Mount Harriet National Park South Button Island National Park Mahatma Gandhi Marine National Park North Button Island National ParkSaddle Peak National Park Andhra Pradesh Papikonda National Park Sri Venkateswara National Park Arunachal Pradesh Mouling National Park Namdapha National Park Assam Dibru-Saikhowa National Park Orang National Park Manas National Park (UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Nameri National Park Kaziranga National Park (Famous for Indian Rhinoceros, UNESCO World Heritage Centre) Bihar Valmiki National Park Chhattisgarh Kanger Ghati National Park Guru Ghasidas (Sanjay) National Park Indravati National Park Goa Mollem National Park Gujarat Marine National Park, Gulf of Kutch Vansda National Park Blackbuck National Park, Velavadar Gir Forest National Park Haryana WWW.BANKINGSHORTCUTS.COM WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/BANKINGSHORTCUTS 1 National Parks in India (State Wise) Kalesar National Park Sultanpur National Park Himachal Pradesh Inderkilla National Park Khirganga National Park Simbalbara National Park Pin Valley National Park Great Himalayan National Park Jammu and Kashmir Salim Ali National Park Dachigam National Park Hemis National Park Kishtwar National Park Jharkhand Hazaribagh National Park Karnataka Rajiv Gandhi (Rameswaram) National Park Nagarhole National Park Kudremukh National Park Bannerghatta National Park (Bannerghatta Biological Park) -

Munnar Landscape Project Kerala

MUNNAR LANDSCAPE PROJECT KERALA FIRST YEAR PROGRESS REPORT (DECEMBER 6, 2018 TO DECEMBER 6, 2019) SUBMITTED TO UNITED NATIONS DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME INDIA Principal Investigator Dr. S. C. Joshi IFS (Retd.) KERALA STATE BIODIVERSITY BOARD KOWDIAR P.O., THIRUVANANTHAPURAM - 695 003 HRML Project First Year Report- 1 CONTENTS 1. Acronyms 3 2. Executive Summary 5 3.Technical details 7 4. Introduction 8 5. PROJECT 1: 12 Documentation and compilation of existing information on various taxa (Flora and Fauna), and identification of critical gaps in knowledge in the GEF-Munnar landscape project area 5.1. Aim 12 5.2. Objectives 12 5.3. Methodology 13 5.4. Detailed Progress Report 14 a.Documentation of floristic diversity b.Documentation of faunistic diversity c.Commercially traded bio-resources 5.5. Conclusion 23 List of Tables 25 Table 1. Algal diversity in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 2. Lichen diversity in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 3. Bryophytes from the HRML study area, Kerala Table 4. Check list of medicinal plants in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 5. List of wild edible fruits in the HRML study area, Kerala Table 6. List of selected tradable bio-resources HRML study area, Kerala Table 7. Summary of progress report of the work status References 84 6. PROJECT 2: 85 6.1. Aim 85 6.2. Objectives 85 6.3. Methodology 86 6.4. Detailed Progress Report 87 HRML Project First Year Report- 2 6.4.1. Review of historical and cultural process and agents that induced change on the landscape 6.4.2. Documentation of Developmental history in Production sector 6.5. -

Ainable Eco-Tourism at Mudumalai Tiger Reserve

International Research Journal of Environment Sciences _____________________________ ___ E-ISSN 2319–1414 Vol. 5(6), 51-56, June (2016) Int. Res. J. Environment Sci. Sustainable Eco -Tourism at Mudumalai Tiger Reserve Carlton R.* and A. Daisy Caroline Mary Department of Environmental Sciences, Bishop Heber College, Tiruchirappalli, India [email protected] Available online at: www.isca.in, www.isca.me Received 23 rd March 2016, revised 16 th May 2016, accepted 9th June 2016 Abstract The present study focuses on Tourism and management practices at Mudumalai Tiger Reserve (MTR) an important and popular wildlife attraction located at one of the hotspots of biodiversity, the Western Ghats. The study focuses on the curre nt practices at the reserve and identifies the s trength, weakness and opportunities in the area. It analyses in the aspects of information to visitors, wildlife experiences, facilities and waste management. Suggestions on sustainable tourism strategies which can result in the better development and management of the Reserve area have been made. The study emphasises the importance of collaboration between Reserve managers and corporate, researchers and public thereby maximise the benefits of research, corporate responsibility and public participation and contribute to conservation and boost the economy. Keywords: Sustainable tourism, Mudumalai Tiger Reserve, Eco-tourism. Introduction of the good tiger po pulation and in an effort to conserve the country's dwindling tiger populations. Mudumalai Tiger As the wildlife tourism industry grows, so have concerns about Reserve is a popular and important eco -tourism destination in threats to wildlife populations and their habitats; a wide range of Tamil Nadu and considered a hotspot of wildlife tourism . -

Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve

Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve April 6, 2021 About Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve was the first biosphere reserve in India established in the year 1986. It is located in the Western Ghats and includes 2 of the 10 biogeographical provinces of India. The total area of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve is 5,520 sq. km. It is located in the Western Ghats between 76°- 77°15‘E and 11°15‘ – 12°15‘N. The annual rainfall of the reserve ranges from 500 mm to 7000 mm with temperature ranging from 0°C during winter to 41°C during summer. The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve encompasses parts of Tamilnadu, Kerala and Karnataka. The Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve falls under the biogeographic region of the Malabar rain forest. The Mudumalai Wildlife Sanctuary, Wayanad Wildlife Sanctuary Bandipur National Park, Nagarhole National Park, Mukurthi National Park and Silent Valley are the protected areas present within this reserve. Vegetational Types of the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve Nature of S.No Forest type Area of occurrence Vegetation Dense, moist and In the narrow Moist multi storeyed 1 valleys of Silent evergreen forest with Valley gigantic trees Nilambur and Palghat 2 Semi evergreen Moist, deciduous division North east part of 3 Thorn Dense the Nilgiri district Savannah Trees scattered Mudumalai and 4 woodland amid woodland Bandipur South and western High elevated Sholas & catchment area, 5 evergreen with grasslands Mukurthi national grasslands park Flora About 3,300 species of flowering plants can be seen out of species 132 are endemic to the Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve. The genus Baeolepis is exclusively endemic to the Nilgiris. -

Assessment of Liverwort and Hornwort Flora of Nilgiri Hills, Western Ghats (India)

Polish Botanical Journal 58(2): 525–537, 2013 DOI: 10.2478/pbj-2013-0038 ASSESSMENT OF LIVERWORT AND HORNWORT FLORA OF NILGIRI HILLS, WESTERN GHATS (INDIA) PR AV E E N KUMAR VERMA 1, AFROZ ALAM & K. K. RAWAT Abstract. Bryophytes are an important part of the flora of the Nilgiri Hills of Western Ghats, a biodiversity hotspot. This paper gives an updated catalogue of the Hepaticae of the Nilgiri Hills. The list includes all available records, based on the authors’ collections and those in LWU and other renowned herbaria. The catalogue of liverworts indicates their substrate and occur- rence, and includes several records new for the Nilgiri bryoflora as well as for Western Ghats. The list of Hepaticae contains 29 families, 55 genera and 164 taxa. The list of Anthocerotae comprises 2 families, 3 genera and 5 taxa belonging to almost all life form types. Key words: Western Ghats, biodiversity hotspot, Tamil Nadu, Bryophyta, Hepaticae, Anthocerotae Praveen Kumar Verma, Rain Forest Research Institute, Deovan, Sotai Ali, Post Box # 136, Jorhat – 785 001 (Assam), India; e-mail: [email protected] Afroz Alam, Department of Bioscience and Biotechnology, Banasthali University, Tonk – 304 022 (Rajasthan), India; e-mail: [email protected] K. K. Rawat, CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute, Rana Pratap Marg, Lucknow – 226 001, India; e-mail: drkkrawat@ rediffmail.com INTRODUCT I ON The Nilgiri Hills of Tamil Nadu are a part of the tropical hill forest, montane wet temperate forests, Nilgiri Biosphere Reserve (NBR), recognized mixed deciduous, montane evergreen (shola grass- under the Man and Biosphere (MAB) Program land) (see also Champion & Seth 1968; Hockings of UNESCO. -

Land Use Change Increases Wildlife Parasite Diversity in Anamalai Hills, Western Ghats, 2 India

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/645044; this version posted May 22, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. 1 Land Use Change Increases Wildlife Parasite Diversity in Anamalai Hills, Western Ghats, 2 India 3 Debapriyo Chakraborty1,2, D. Mahender Reddy1, Sunil Tiwari1, Govindhaswamy 4 Umapathy1* 5 1 CSIR-Laboratory for the Conservation of Endangered Species, Centre for Cellular and 6 Molecular Biology, Hyderabad 500048, India 7 2 Present address: EP57 P C Ghosh Road, Kolkata 700048, India 8 *[email protected] 9 10 ABSTRACT 11 Anthropogenic landscape change such as land use change and habitat fragmentation are 12 known to alter wildlife diversity. Since host and parasite diversities are strongly connected, 13 landscape changes are also likely to change wildlife parasite diversity with implication for 14 wildlife health. However, research linking anthropogenic landscape change and wildlife 15 parasite diversity is limited, especially comparing effects of land use change and habitat 16 fragmentation, which often cooccur but may affect parasite diversity substantially 17 differently. Here, we assessed how anthropogenic land use change (presence of plantation, 18 livestock foraging and human settlement) and habitat fragmentation may change the 19 gastrointestinal parasite diversity of wild mammalian host species (n=23) in Anamalai hills, 20 India. We found that presence of plantations, and potentially livestock, significantly 21 increased parasite diversity due possibly to spillover of parasites from livestock to wildlife. 22 However, effect of habitat fragmentation on parasite diversity was not significant.