Introduction: Studying Election Fraud R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cabinet, President, Referendum: Turkey's Complex Political Calendar | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 1271 Cabinet, President, Referendum: Turkey's Complex Political Calendar Aug 10, 2007 Brief Analysis n August 9, the Turkish parliament elected Koksal Toptan, a deputy from the Justice and Development Party O (AKP) as its speaker. The AKP, which won 46 percent of the vote in July 22 parliamentary elections, controls 341 seats in the 550-member Turkish parliament. Thus has Turkey begun a very busy political season, with serious issues put off since the April constitutional crisis over the AKP's attempt to appoint its foreign minister, Abdullah Gul, as president. The new parliament's first order of business will be securing a vote of confidence for the AKP's new cabinet. Then the legislature will face the constitutional mandate of electing a new president, an executive post with important prerogatives such as appointing judges to the secular constitutional court. But while the Turkish parliament prepares to elect a president, Turks will vote in an October 21 referendum on constitutional amendments that would stipulate the direct popular election of the president. What are the timelines for these overlapping political processes and how smoothly will each of them run? Round I: Forming a New Government The next step for the AKP is to form government. According to Article 116 of the Turkish constitution, a new cabinet of ministers must be formed and then approved by the president and the parliament within forty-five days after the president authorizes the leader of the winning party to form government. The process of forming a government commenced on August 6, after Turkish president Ahmet Necdet Sezer commissioned AKP leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan to select a cabinet. -

The Case for Electoral Reform: a Mixed Member Proportional System

1 The Case for Electoral Reform: A Mixed Member Proportional System for Canada Brief by Stephen Phillips, Ph.D. Instructor, Department of Political Science, Langara College Vancouver, BC 6 October 2016 2 Summary: In this brief, I urge Parliament to replace our current Single-Member Plurality (SMP) system chiefly because of its tendency to distort the voting intentions of citizens in federal elections and, in particular, to magnify regional differences in the country. I recommend that SMP be replaced by a system of proportional representation, preferably a Mixed Member Proportional system (MMP) similar to that used in New Zealand and the Federal Republic of Germany. I contend that Parliament has the constitutional authority to enact an MMP system under Section 44 of the Constitution Act 1982; as such, it does not require the formal approval of the provinces. Finally, I argue that a national referendum on replacing the current SMP voting system is neither necessary nor desirable. However, to lend it political legitimacy, the adoption of a new electoral system should only be undertaken with the support of MPs from two or more parties that together won over 50% of the votes cast in the last federal election. Introduction Canada’s single-member plurality (SMP) electoral system is fatally flawed. It distorts the true will of Canadian voters, it magnifies regional differences in the country, and it vests excessive political power in the hands of manufactured majority governments, typically elected on a plurality of 40% or less of the popular vote. The adoption of a voting system based on proportional representation would not only address these problems but also improve the quality of democratic government and politics in general. -

Values, Volatility and Voting: Understanding Voters in England 2015-2019

VALUES, VOLATILITY AND VOTING: UNDERSTANDING VOTERS IN ENGLAND 2015-2019 Paula Surridge Paula Surridge School of Sociology, Politics and International Studies University of Bristol and UK in a Changing Europe [email protected] Please note: This paper is an early draft and may develop further before publication as new insights become available and modelling is refined. Comments are very welcome via [email protected] 1 ABSTRACT The EU referendum and subsequent general elections in the UK have renewed interest in the influence of values and identity on voting behaviour. This paper uses data from the British Election Study Internet Panel to study the influence of ‘core’ political values on voting behaviour in England at the 2015, 2017 and 2019 general elections. Using a two- dimensional model of political values, the paper shows that both the ‘old’ political values of left and right (associated with economics) and the ‘new’ political values (measured here as ‘liberal-authoritarian’ values) were important in vote choices at each of the three elections. Using the ‘funnel of causality’ model, it shows that values are a more important influence when voters have weaker attachments to political parties and that the interaction between the dimensions is critical for understanding voting patterns. 2 INTRODUCTION Prior to 2016, the study of elections in the UK had largely turned away from values-based models with those based on the ‘valence’ effects of party identity, leadership and competence almost ‘universally accepted’ (Denver and Garnett, 2014). Whilst the EU Referendum (and subsequent general elections in 2017 and 2019) have renewed interest in values and identity as influences on political behaviour, it is a mistake to think of values divides as ‘new’ or as created by the EU referendum. -

V Proof of Residence for Voter Registration

v Proof Of Residence For Voter Registration What Do I Need To Know About Proof Of Residence For Voter Registration? A Proof of Residence document is a document that proves where you live in Wisconsin and is only used when registering to vote. Photo ID is separate, you only show photo ID to prove who you are when you request an absentee ballot or receive a ballot at your polling place. When Do I Have To Provide Proof Of Residence? All voters MUST provide a Proof of Residence Document. If you register to vote by mail, in-person in your clerk’s office, with a Election Registration Official, or at your polling place on Election Day, you need to provide a Proof of Residence document. * If you are an active military voter, or a permanent overseas voter (with no intent to return to the U.S.) you do not need to provide a Proof of Residence document. What Documents Can I Use As Proof Of Residence For Registering? All Proof of Residence documents must include the voter’s name and current residential address. • A current and valid State of Wisconsin Driver License or State ID card. • Any other official identification card or license issued by a Wisconsin governmental body or unit. • Any identification card issued by an employer in the normal course of business and bearing a photo of the card holder, but not including a business card. • A real estate tax bill or receipt for the current year or the year preceding the date of the election. • A university, college, or technical college identification card (must include photo) ONLY if the voter provides a fee receipt dated within the last 9 months or the institution provides a certified housing list, that indicates citizenship, to the municipal clerk. -

Gerrymandering Becomes a Problem

VOLUME TWENTY FOUR • NUMBER TWO WINTER 2020 THE SPECIAL ELECTION EDITION A LEGAL NEWSPAPER FOR KIDS Gerrymandering Becomes a Problem Battling Over for the States to Resolve How to Elect by Phyllis Raybin Emert a President by Michael Barbella Gerrymandering on a partisan basis is not new to politics. The term gerrymander dates back to the 1800s when it was used to mock The debate on how the President Massachusetts Governor Elbridge Gerry, who manipulated congressional of the United States should be elected lines in the state until the map of one district looked like a salamander. is almost as old as the country itself. Redistricting, which is the redrawing of district maps, happens every Contrary to popular belief, voters 10 years after the U.S. Census takes place. Whatever political party is do not elect the president and vice in power at that time has the advantage since, in most states, they president directly; instead, they choose are in charge of drawing the maps. electors to form an Electoral College “Partisan gerrymandering refers to the practice of politicians where the official vote is cast. drawing voting districts for their own political advantage,” During the Constitutional Convention says Eugene D. Mazo, a professor at Rutgers Law School and of 1787, a an expert on election law and the voting process. few ways to Professor Mazo explains that politicians, with the use of advanced computer elect the chief technology, use methods of “packing” and “cracking” to move voters around to executive were different state districts, giving the edge to one political party. -

Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence Of

Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics: Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Elections are essential elements of democratic systems. Unfortunately, abuse and manipulation (including voter intimidation, vote buying or ballot stuffing) can distort these processes. However, little attention has been paid to an intrinsic part of this threat: the conditions and opportunities for criminal interference in the electoral process. Most worrying, few scholars have examined the underlying conditions that make elections vulnerable to organized criminal involvement. This report addresses these gaps in knowledge by analysing the vulnerabilities of electoral processes to illicit interference (above all by organized crime). It suggests how national and international authorities might better protect these crucial and coveted elements of the democratic process. Case studies from Georgia, Mali and Mexico illustrate these challenges and provide insights into potential ways to prevent and mitigate the effects of organized crime on elections. International IDEA Clingendael Institute ISBN 978-91-7671-069-2 Strömsborg P.O. Box 93080 SE-103 34 Stockholm 2509 AB The Hague Sweden The Netherlands T +46 8 698 37 00 T +31 70 324 53 84 F +46 8 20 24 22 F +31 70 328 20 02 9 789176 710692 > [email protected] [email protected] www.idea.int www.clingendael.nl ISBN: 978-91-7671-069-2 Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Protecting Politics Deterring the Influence of Organized Crime on Elections Series editor: Catalina Uribe Burcher Lead authors: Ivan Briscoe and Diana Goff © 2016 International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance © 2016 Netherlands Institute of International Relations (Clingendael Institute) International IDEA Strömsborg SE-103 34 Stockholm Sweden Tel: +46 8 698 37 00, fax: +46 8 20 24 22 Email: [email protected], website: www.idea.int Clingendael Institute P.O. -

Extreme Gerrymandering & the 2018 Midterm

EXTREME GERRYMANDERING & THE 2018 MIDTERM by Laura Royden, Michael Li, and Yurij Rudensky Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER FOR JUSTICE The Brennan Center for Justice at NYU School of Law is a nonpartisan law and policy institute that works to reform, revitalize — and when necessary defend — our country’s systems of democracy and justice. At this critical moment, the Brennan Center is dedicated to protecting the rule of law and the values of Constitutional democracy. We focus on voting rights, campaign finance reform, ending mass incarceration, and preserving our liberties while also maintaining our national security. Part think tank, part advocacy group, part cutting-edge communications hub, we start with rigorous research. We craft innovative policies. And we fight for them — in Congress and the states, the courts, and in the court of public opinion. ABOUT THE CENTER’S DEMOCRACY PROGRAM The Brennan Center’s Democracy Program works to repair the broken systems of American democracy. We encourage broad citizen participation by promoting voting and campaign finance reform. We work to secure fair courts and to advance a First Amendment jurisprudence that puts the rights of citizens — not special interests — at the center of our democracy. We collaborate with grassroots groups, advocacy organizations, and government officials to eliminate the obstacles to an effective democracy. ABOUT THE BRENNAN CENTER’S PUBLICATIONS Red cover | Research reports offer in-depth empirical findings. Blue cover | Policy proposals offer innovative, concrete reform solutions. White cover | White papers offer a compelling analysis of a pressing legal or policy issue. -

OEA/Ser.G CP/Doc. 4115/06 8 May 2006 Original: English REPORT OF

OEA/Ser.G CP/doc. 4115/06 8 May 2006 Original: English REPORT OF THE ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION IN BOLIVIA PRESIDENTIAL AND PREFECTS ELECTIONS 2005 This document is being distributed to the permanent missions and will be presented to the Permanent Council of the Organization ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN STATES REPORT OF THE ELECTORAL OBSERVATION MISSION IN BOLIVIA PRESIDENTIAL AND PREFECTS ELECTIONS 2005 Secretariat for Political Affairs This version is subject to revision and will not be available to the public pending consideration, as the case may be, by the Permanent Council CONTENTS MAIN ABBREVIATIONS vi CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 A. Electoral Process of December 2005 1 B. Legal and Electoral Framework 3 1. Electoral officers 4 2. Political parties 4 3. Citizen groups and indigenous peoples 5 4. Selection of prefects 6 CHAPTER II. MISSION BACKGROUND, OBJECTIVES AND CHARACTERISTICS 7 A. Mission Objectives 7 B. Preliminary Activities 7 C. Establishment of Mission 8 D. Mission Deployment 9 E. Mission Observers in Political Parties 10 F. Reporting Office 10 CHAPTER III. OBSERVATION OF PROCESS 11 A. Electoral Calendar 11 B. Electoral Training 11 1. Training for electoral judges, notaries, and board members11 2. Disseminating and strengthening democratic values 12 C. Computer System 13 D. Monitoring Electoral Spending and Campaigning 14 E. Security 14 CHAPTER IV. PRE-ELECTION STAGE 15 A. Concerns of Political Parties 15 1. National Electoral Court 15 2. Critical points 15 3. Car traffic 16 4. Sealing of ballot boxes 16 5. Media 17 B. Complaints and Reports 17 1. Voter registration rolls 17 2. Disqualification 17 3. -

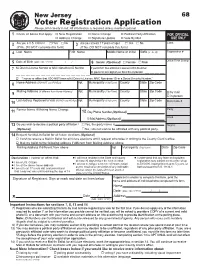

New Jersey 68 Voter Registration Application Please Print Clearly in Ink

New Jersey 68 Voter Registration Application Please print clearly in ink. All information is required unless marked optional. 1 Check all boxes that apply: o New Registration o Name Change o Political Party Affiliation FOR OFFICIAL o Address Change o Signature Update o Vote By Mail USE ONLY 2 Are you a U.S. Citizen? o Yes o No 3 Are you at least 17 years of age? o Yes o No Clerk (If No, DO NOT complete this form) (If No, DO NOT complete this form) 4 Last Name First Name Middle Name or Initial Suffix (Jr., Sr., III) Registration # Office Time Stamp 5 Date of Birth (MM / DD / YYYY) / / 6 Gender (Optional) o Female o Male 7 NJ Driver’s License Number or MVC Non-driver ID Number If you DO NOT have a NJ Driver’s License or MVC Non-Driver ID, provide the last 4 digits of your Social Security Number. __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ __ o “I swear or affirm that I DO NOT have a NJ Driver’s License, MVC Non-driver ID or a Social Security Number.” Home Address (DO NOT use PO Box) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code 8 Mailing Address (If different from Home Address) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code o 9 by mail o in person Last Address Registered to Vote (DO NOT use PO Box) Apt. Municipality (City/Town) County State Zip Code 10 Muni Code # Former Name if Making Name Change Party 11 12 Day Phone Number (Optional) Ward E-Mail Address (Optional) 13 Do you wish to declare a political party affiliation? o Yes, the party name is . -

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations

Combating Corruption in Latin America: Congressional Considerations May 21, 2019 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R45733 SUMMARY R45733 Combating Corruption in Latin America May 21, 2019 Corruption of public officials in Latin America continues to be a prominent political concern. In the past few years, 11 presidents and former presidents in Latin America have been forced from June S. Beittel, office, jailed, or are under investigation for corruption. As in previous years, Transparency Coordinator International’s Corruption Perceptions Index covering 2018 found that the majority of Analyst in Latin American respondents in several Latin American nations believed that corruption was increasing. Several Affairs analysts have suggested that heightened awareness of corruption in Latin America may be due to several possible factors: the growing use of social media to reveal violations and mobilize Peter J. Meyer citizens, greater media and investor scrutiny, or, in some cases, judicial and legislative Specialist in Latin investigations. Moreover, as expectations for good government tend to rise with greater American Affairs affluence, the expanding middle class in Latin America has sought more integrity from its politicians. U.S. congressional interest in addressing corruption comes at a time of this heightened rejection of corruption in public office across several Latin American and Caribbean Clare Ribando Seelke countries. Specialist in Latin American Affairs Whether or not the perception that corruption is increasing is accurate, it is nevertheless fueling civil society efforts to combat corrupt behavior and demand greater accountability. Voter Maureen Taft-Morales discontent and outright indignation has focused on bribery and the economic consequences of Specialist in Latin official corruption, diminished public services, and the link of public corruption to organized American Affairs crime and criminal impunity. -

Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21St Century

This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting — © 2004 Bev Harris Rights reserved to Talion Publishing/ Black Box Voting ISBN 1-890916-90-0. You can purchase copies of this book at www.Amazon.com. Black Box Voting Ballot Tampering in the 21st Century By Bev Harris Talion Publishing / Black Box Voting This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Contents © 2004 by Bev Harris ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Jan. 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form whatsoever except as provided for by U.S. copyright law. For information on this book and the investigation into the voting machine industry, please go to: www.blackboxvoting.org Black Box Voting 330 SW 43rd St PMB K-547 • Renton, WA • 98055 Fax: 425-228-3965 • [email protected] • Tel. 425-228-7131 This free internet version is available at www.BlackBoxVoting.org Black Box Voting © 2004 Bev Harris • ISBN 1-890916-90-0 Dedication First of all, thank you Lord. I dedicate this work to my husband, Sonny, my rock and my mentor, who tolerated being ignored and bored and galled by this thing every day for a year, and without fail, stood fast with affection and support and encouragement. He must be nuts. And to my father, who fought and took a hit in Germany, who lived through Hitler and saw first-hand what can happen when a country gets suckered out of democracy. And to my sweet mother, whose an- cestors hosted a stop on the Underground Railroad, who gets that disapproving look on her face when people don’t do the right thing. -

Direct Democracy an Overview of the International IDEA Handbook © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2008

Direct Democracy An Overview of the International IDEA Handbook © International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2008 International IDEA publications are independent of specific national or political interests. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily represent the views of International IDEA, its Board or its Council members. The map presented in this publication does not imply on the part of the Institute any judgement on the legal status of any territory or the endorsement of such boundaries, nor does the placement or size of any country or territory reflect the political view of the Institute. The map is created for this publication in order to add clarity to the text. Applications for permission to reproduce or translate all or any part of this publication should be made to: International IDEA SE -103 34 Stockholm Sweden International IDEA encourages dissemination of its work and will promptly respond to requests for permission to reproduce or translate its publications. Cover design by: Helena Lunding Map design: Kristina Schollin-Borg Graphic design by: Bulls Graphics AB Printed by: Bulls Graphics AB ISBN: 978-91-85724-54-3 Contents 1. Introduction: the instruments of direct democracy 4 2. When the authorities call a referendum 5 Procedural aspects 9 Timing 10 The ballot text 11 The campaign: organization and regulation 11 Voting qualifications, mechanisms and rules 12 Conclusions 13 3. When citizens take the initiative: design and political considerations 14 Design aspects 15 Restrictions and procedures 16 Conclusions 18 4. Agenda initiatives: when citizens can get a proposal on the legislative agenda 19 Conclusions 21 5.