Our Journey to Mogadishu Fear and Hope

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

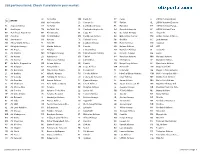

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 of 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report

IATA CLEARING HOUSE PAGE 1 OF 21 2021-09-08 14:22 EST Member List Report AGREEMENT : Standard PERIOD: P01 September 2021 MEMBER CODE MEMBER NAME ZONE STATUS CATEGORY XB-B72 "INTERAVIA" LIMITED LIABILITY COMPANY B Live Associate Member FV-195 "ROSSIYA AIRLINES" JSC D Live IATA Airline 2I-681 21 AIR LLC C Live ACH XD-A39 617436 BC LTD DBA FREIGHTLINK EXPRESS C Live ACH 4O-837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. B Suspended Non-IATA Airline M3-549 ABSA - AEROLINHAS BRASILEIRAS S.A. C Live ACH XB-B11 ACCELYA AMERICA B Live Associate Member XB-B81 ACCELYA FRANCE S.A.S D Live Associate Member XB-B05 ACCELYA MIDDLE EAST FZE B Live Associate Member XB-B40 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS AMERICAS INC B Live Associate Member XB-B52 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS INDIA LTD. D Live Associate Member XB-B28 ACCELYA SOLUTIONS UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B70 ACCELYA UK LIMITED A Live Associate Member XB-B86 ACCELYA WORLD, S.L.U D Live Associate Member 9B-450 ACCESRAIL AND PARTNER RAILWAYS D Live Associate Member XB-280 ACCOUNTING CENTRE OF CHINA AVIATION B Live Associate Member XB-M30 ACNA D Live Associate Member XB-B31 ADB SAFEGATE AIRPORT SYSTEMS UK LTD. A Live Associate Member JP-165 ADRIA AIRWAYS D.O.O. D Suspended Non-IATA Airline A3-390 AEGEAN AIRLINES S.A. D Live IATA Airline KH-687 AEKO KULA LLC C Live ACH EI-053 AER LINGUS LIMITED B Live IATA Airline XB-B74 AERCAP HOLDINGS NV B Live Associate Member 7T-144 AERO EXPRESS DEL ECUADOR - TRANS AM B Live Non-IATA Airline XB-B13 AERO INDUSTRIAL SALES COMPANY B Live Associate Member P5-845 AERO REPUBLICA S.A. -

Procurement of Framework Agreement with Travel Agency Service Providers

INVITATION TO BID (ITB) No. ITB No. N_64_2020_SOM PROCUREMENT OF FRAMEWORK AGREEMENT WITH TRAVEL AGENCY SERVICE PROVIDERS Date: 2nd April 2020 Dear Sir/Madam, You are kindly requested to submit your bid for services described in this ITB. Bidders requesting clarification on provisions stipulated in this ITB shall communicate those in writing to [email protected] not later than 72 hours prior to the deadline for submission of bids. The requests for clarification will have “Request for clarifications for ITB No. N_64_2020_SOM” mentioned in the subject. This ITB includes the following documents: This ITB is comprised of: Instructions to bidders Terms of Reference Annex A Bid Submission Form Annex B Price Schedule Annex C IDLO Special Conditions of Contract Annex D IDLO General Terms and Conditions for the Procurement of Services Annex E Supplier Code of Conduct Annex F Bids shall be submitted to the following secure e-mail address: [email protected] no later than 17th April 2020 at 13:00 Somali Local Time and should have “Bid for N_64_2020_SOM” mentioned in the subject. Bids shall not exceed 20MB in size. ITB N_64_2020_SOM Instructions to Bidders: Bidder’s proposal MUST meet the following qualification requirements to be considered for price evaluation. QUALIFICATION REQUIREMENTS Bidders are required to submit the following mandatory documents to ascertain their qualification 1 Accredited IATA or equivalent Travel Agent duly licensed to operate in Somalia and Indicating which booking system the company uses (copy of the IATA membership to be Submitted). 2 Minimum two (2) years of operational experience and registered as a travel agent 3 Minimum two (2) year contract of similar nature and complexity with International/regional inter-governmental agencies including the UN, the Government of Somalia, NGOs/INGOs, Embassies or multi-national Corporate Entities indicating Contactable references for verification. -

Attachment F – Participants in the Agreement

Revenue Accounting Manual B16 ATTACHMENT F – PARTICIPANTS IN THE AGREEMENT 1. TABULATION OF PARTICIPANTS 0B 475 BLUE AIR AIRLINE MANAGEMENT SOLUTIONS S.R.L. 1A A79 AMADEUS IT GROUP SA 1B A76 SABRE ASIA PACIFIC PTE. LTD. 1G A73 Travelport International Operations Limited 1S A01 SABRE INC. 2D 54 EASTERN AIRLINES, LLC 2I 156 STAR UP S.A. 2I 681 21 AIR LLC 2J 226 AIR BURKINA 2K 547 AEROLINEAS GALAPAGOS S.A. AEROGAL 2T 212 TIMBIS AIR SERVICES 2V 554 AMTRAK 3B 383 Transportes Interilhas de Cabo Verde, Sociedade Unipessoal, SA 3E 122 MULTI-AERO, INC. DBA AIR CHOICE ONE 3J 535 Jubba Airways Limited 3K 375 JETSTAR ASIA AIRWAYS PTE LTD 3L 049 AIR ARABIA ABDU DHABI 3M 449 SILVER AIRWAYS CORP. 3S 875 CAIRE DBA AIR ANTILLES EXPRESS 3U 876 SICHUAN AIRLINES CO. LTD. 3V 756 TNT AIRWAYS S.A. 3X 435 PREMIER TRANS AIRE INC. 4B 184 BOUTIQUE AIR, INC. 4C 035 AEROVIAS DE INTEGRACION REGIONAL 4L 174 LINEAS AEREAS SURAMERICANAS S.A. 4M 469 LAN ARGENTINA S.A. 4N 287 AIR NORTH CHARTER AND TRAINING LTD. 4O 837 ABC AEROLINEAS S.A. DE C.V. 4S 644 SOLAR CARGO, C.A. 4U 051 GERMANWINGS GMBH 4X 805 MERCURY AIR CARGO, INC. 4Z 749 SA AIRLINK 5C 700 C.A.L. CARGO AIRLINES LTD. 5J 203 CEBU PACIFIC AIR 5N 316 JOINT-STOCK COMPANY NORDAVIA - REGIONAL AIRLINES 5O 558 ASL AIRLINES FRANCE 5T 518 CANADIAN NORTH INC. 5U 911 TRANSPORTES AEREOS GUATEMALTECOS S.A. 5X 406 UPS 5Y 369 ATLAS AIR, INC. 50 Standard Agreement For SIS Participation – B16 5Z 225 CEMAIR (PTY) LTD. -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

AFRAA Annual Report 2019

IRLINES ASS A PAGNIES O OM AERI C 20N S C EN 19 E N I A D ES A N A T C IO F I T R I I O R IA C C A I N F O N S E S A S A ANNUAL AFRAA REPORT Amadeus Airline Platform Bringing SIMPLICITY to airlines You can follow us on: AmadeusITGroup amadeus.com/airlineplatform AFRAA Executive Committee (EXC) Members 2019 AIR MAURITIUS (MK) RWANDAIR (WB) PRESIDENT OF AFRAA CHAIRPERSON OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Mr. Somas Appavou Ms. Yvonne Makolo Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer CONGO AIRWAYS (8Z) KENYA AIRWAYS (KQ) CAMAIR-CO (QC) Mr. Desire Balazire Esono Mr. Sebastian Mikosz Mr. Louis Roger Njipendi Kouotou 1st Vice Chairman of the EXC 2nd Vice Chairman of the EXC Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer ROYAL AIR MAROC (AT) EGYPTAIR (MS) TUNISAIR (TU) Mr. Abdelhamid Addou Capt. Ahmed Adel Mr. Ilyes Mnakbi Chief Executive Officer Chairman & Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES (ET) AIR ZIMBABWE (UM) AIR NAMIBIA (SW) MAURITANIA AIRLINES (L6) Mr. Tewolde GebreMariam Mr. Joseph Makonise Mr. Xavier Masule Mrs. Amal Mint Maoulod Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer Chief Executive Officer ANNUAL REPORT 2019 I Foreword raffic growth in Africa has been consistently increasing since 2011. The demand for air passenger services remained strong in 2018 with a 6.9% year Ton year growth. Those good results were supported by the good global economic environment particularly in the first half of the year. Unlike passenger traffic, air freight demand recorded a very weak performance in 2018 compared to 2017. -

S 2019 858 E.Pdf

United Nations S/2019/858* Security Council Distr.: General 1 November 2019 Original: English Letter dated 1 November 2019 from the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia addressed to the President of the Security Council On behalf of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia, and in accordance with paragraph 54 of Security Council resolution 2444 (2018), I have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel of Experts on Somalia. In this connection, the Committee would appreciate it if the present letter and the report were brought to the attention of the members of the Security Council and issued as a document of the Council. (Signed) Marc Pecsteen de Buytswerve Chair Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia * Reissued for technical reasons on 14 November 2019. 19-16960* (E) 141119 *1916960* S/2019/858 Letter dated 27 September 2019 from the Panel of Experts on Somalia addressed to the Chair of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolution 751 (1992) concerning Somalia In accordance with paragraph 54 of Security Council resolution 2444 (2018), we have the honour to transmit herewith the final report of the Panel of Experts on Somalia. (Signed) Jay Bahadur Coordinator Panel of Experts on Somalia (Signed) Mohamed Abdelsalam Babiker Humanitarian expert (Signed) Nazanine Moshiri Armed groups expert (Signed) Brian O’Sullivan Armed groups/natural resources expert (Signed) Matthew Rosbottom Finance expert (Signed) Richard Zabot Arms expert 2/161 19-16960 S/2019/858 Summary During the first reporting period of the Panel of Experts on Somalia, the use by Al-Shabaab of improvised explosive devices reached its greatest extent in Somali history, with a year-on-year increase of approximately one third. -

Rebuilding Resilient and Sustainable Agriculture in Somalia Public Disclosure Authorized Photo Credits: Cover & Inside ©FAO Somalia

SOMALIA COUNTRY ECONOMIC MEMORANDUM Volume I Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Rebuilding Resilient and Sustainable Agriculture in Somalia Public Disclosure Authorized Photo credits: Cover & Inside ©FAO Somalia SOMALIA: Rebuilding Resilient and Sustainable Agriculture Copyright © 2018 by International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations ISBN 978-92-5-130419-8 (FAO) © FAO, 2018 Disclaimer: The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments and members represented by either institution. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. -

Report of the Somalia and Eritrea Monitoring Group

ADVANCED COPY – CONFIDENTIAL Letter dated 27 June 2012 from the members of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea addressed to the Chairman of the Security Council Committee pursuant to resolutions 751 (1992) and 1907 (2009) concerning Somalia and Eritrea We have the honour to transmit herewith the report focusing on Somalia of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea in accordance with paragraph 6 (m) of Security Council resolution 2002 (2011). (Signed) Matt Bryden Coordinator Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea (Signed) Emmanuel Deisser Arms Expert (Signed) Aurélien Llorca Aviation Expert (Signed) Jörg Roofthooft Maritime Expert (Signed) Ghassan Schbley Finance Expert (Signed) Babatunde Taiwo Armed Groups Expert (Signed) Kristele Younes Humanitarian Expert ADVANCED COPY - CONFIDENTIAL 2 Report of the Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea pursuant to Security Council resolution 2002 (2011) Contents Page Abbreviations 5 Summary 6 I. Introduction 9 A. Mandate 9 B. Methodology 9 II. Acts that threaten the peace, security and stability of Somalia 11 A. Public sector financial mismanagement and corruption 11 B. Harakaat al-Shabaab al-Mujaahidiin 14 C. Al-Shabaab as a regional and international threat 15 D. Piracy and kidnap for ransom (KFR) 16 III. Violations of the general and complete arms embargo 19 A. Foreign military operations in Somalia 20 B. Private Security Companies (PSCs) 21 C. Private Maritime Security Companies/ Floating Armouries 24 D. Non-compliance 24 IV. Obstruction of Humanitarian Assistance 25 A. Denial of access 25 B. Diversion and misappropriation of humanitarian assistance 26 C. Best practices 27 V. Violations of International Humanitarian Law 27 A. Attacks on civilians 28 B. -

338 Partners Found. Check If Available in Your Market

339 partners found. Check if available in your market. JU Air Serbia MO Calm Air XY flynas JJ LATAM Airlines Brasil HR-169 HM Air Seychelles QC Camair-Co 5F FlyOne XL LATAM Airlines Ecuador A3 Aegean Airlines VT Air Tahiti KR Cambodia Airways FA FlySafair PZ LATAM Airlines Parag… EI Aer Lingus TN Air Tahiti Nui K6 Cambodia Angkor Air GA Garuda Indonesia LP LATAM Airlines Peru AR Aerolineas Argentinas NF Air Vanuatu 9K Cape Air A9 Georgian Airways O2 Linear Air VW Aeromar UM Air Zimbabwe BW Caribbean Airlines G3 GOL Linhas Aereas TM Linhas Aereas de Moc… AM Aeromexico SB Aircalin CX Cathay Pacific GF Gulf Air FC Link Airways AW Africa World Airlines TL Airnorth KX Cayman Airways HR Hahn Air Lines LM Loganair 8U Afriqiyah Airways AS Alaska Airlines 5Z CemAir HU Hainan Airlines LO LOT AH Air Algerie AZ Alitalia CI China Airlines HA Hawaiian Airlines 8L Lucky Air 3S Air Antilles NH All Nippon Airways MU China Eastern Airlines 2L Helvetic Airways LG Luxair KC Air Astana Z8 Amaszonas WX CityJet H9 Himalaya Airlines MH Malaysia Airlines UU Air Austral IZ Arkia Israel Airlines CC CM Airlines UO HK Express AE Mandarin Airlines BT Air Baltic Corporation OZ Asiana Airlines DE Condor HX Hong Kong Airlines L6 Mauritania Airlines KF Air Belgium KP ASky Airlines CM Copa Airlines MR Hunnu Air 2M Maya Island Air BP Air Botswana 5O ASL Airlines France SS Corsair Intl FI Icelandair 5G Mayair / Aerocuahonte 2J Air Burkina RC Atlantic Airways OU Croatia Airlines JY interCaribbean Airways OM MIAT - Mongolian Airli… AC Air Canada GR Aurigny Air Services CU Cubana de Aviacion 6H Israir Airlines ME Middle East Airlines TX Air Caraibes HZ Aurora Airlines CY Cyprus Airways JL Japan Airlines M9 Motor Sich Airlines 3C Air Chathams YK Avia Traffic Company OK Czech Airlines NU Japan Transocean Air 8M Myanmar Airways Intl. -

Country of Origin Information Report on South and Central Somalia

Country of Origin Information Report on South and Central Somalia Date March 2019 Page 1 of 62 Country of Origin Information Report on South and Central Somalia | March 2019 Document details The Hague Text by: Directorate for Sub-Saharan Africa Country of Origin Information Cluster (DAF/CAB) Disclaimer: The Dutch version of this report is leading. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands cannot be held accountable for misinterpretations based on the English version of the report. Page 2 of 62 Country of Origin Information Report on South and Central Somalia | March 2019 Table of contents Document details ............................................................................................2 Table of contents .............................................................................................3 Introduction ....................................................................................................5 1 Country information .................................................................................... 7 1.1 Political developments ......................................................................................7 1.1.1 Al-Shabaab ................................................................................................... 10 1.2 The security situation ..................................................................................... 17 1.2.1 General ........................................................................................................ 17 1.2.2 Security situation per member -

DUBAI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT DXB W13 Start of Season Report

DUBAI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT DXB W13 Start of Season Report Change from W12 Change from W12 W13 Start Key Statistics Start End Air Transport Movements 172,628 5.1% 10.8% Total Seats 44,733,303 14.2% 22.5% Average Seats per Passenger ATM 251 5.3% 5.0% Contents Page CONSTRAINTS BY TERMINAL 2 CODE F AIRCRAFT ARRIVALS AND DEPARTURES 3 AIR TRANSPORT MOVEMENT STATISTICS 4 SEATS AND SEATS PER MOVEMENT STATISTICS 5 DISTRIBUTION OF SCHEDULE ADJUSTMENTS 6-7 TOP 10 AIRLINES BY ATMS AND SEATS 8 TOP 20 SESTINATIONS BY ATMS AND SEATS 9 RUNWAY MOVEMENT ALLOCATION - R60 - EMIRATES, FLYDUBAI AND OTHER CARRIERS 10 RUNWAY MOVEMENT ALLOCATION - R10 11 TERMINAL 1 PEAK WEEK HISTOGRAMS 12 TERMINAL 2 PEAK WEEK HISTOGRAMS 13 TERMINAL 2 GATE UTILISATION 13 TERMINAL 3 PEAK WEEK HISTOGRAMS 14 GLOSSARY 15 Data in this report is current as of 14th March 2013 No warranty whether expressed or implied as to the completeness, accuracy, fitness for purpose, or satisfactory quality is given by ACL regarding the information in this report, which is provided by third parties. Accordingly, ACL excludes all liability with regard to such data. The contents of this report may not be reproduced without the written consent of ACL. PRIMARY CONSTRAINTS BY TERMINAL OK R10 R60 AA GRA GRD V10 Grand Total Arrivals 83,248 2,058 1,009 83 242 22 86,662 Departures 83,127 1,866 739 216 22 85,970 Grand Total 166,375 3,924 1,748 83 216 264 22 172,632 Row Labels OK R10 R60 AA GRA GRD V10 Grand Total Arrivals 96.1% 2.4% 1.2% 0.1% 0.0% 0.3% 0.0% 100.0% Departures 96.7% 2.2% 0.9% 0.0% 0.3% 0.0% 0.0% -

Coastal Livelihoods in the Republic of Somalia

COASTAL LIVELIHOODS IN THE REPUBLIC OF SOMALIA GENERAL INTRODUCTION The Agulhas and Somali Current Large Marine Ecosystems (ASCLME) project is focused on the two large marine ecosystems of the Western Indian Ocean (WIO) region, covering nine countries that are directly influenced by these current systems. It is estimated that at least fifty-six million people are reliant either directly or indirectly on the goods and services provided by these two current systems. The ASCLME project aims to support these countries in their efforts to collectively manage the marine resources on which their people and economies depend. Fisheries and other key coastal activities, including various forms of tourism, aquaculture, shipping and coastal transport, the energy sector, agriculture and forestry, are very important contributors to the economies of the countries of the WIO. In recognition of the complexity and importance of these activities, a Coastal Livelihoods Assessment (CLA) component was developed for the ASCLME project. The CLA component had three main objectives: • to collect as much existing information as possible about the main coastal activities in the nine participating countries as a contribution to the national Marine Ecosystem Diagnostic Analyses (MEDAs); • to make input into ensuring that this information is stored and organised in a manner that will allow easy access and maximum utility to multiple stakeholders, both during and after the lifetime of the ASCLME Project; • to review and sythesise the information collected in order to provide useful inputs to the TDA and SAP processes. In order to achieve these objectives, the CLA component was separated into three distinct phases, with the first phase kicking off in May 2009.