Manchester Ii Shrinking to Grow? Shrinking to Grow? Iii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Directory. [Slater's

2110 OFFICIAL DIRECTORY. [SLATER'S COU~CILLORS. WARD. COLLEGIATE CHURCH WARD. Hinchcliffe Thomas Henry. ••.•.••.• St. Luke's Alderman. BinchlifIe lsaac.•.•.•• ,.•.•...•.... St. John's I:John Royle, 36 Dantzio street Bodkin Henry ••••••••••••••••••.• Longsigllt Holden Wllliam.................. .• Hll.rpurhey Councillors. Howarth l}eorge ••••.•••••.•••...• N ew Cr(J~s !John Richard Smith, 27 ~hfield road, Urmston Howell Hiram .J:;;dward •••••..•.•.. ClteethRJn "Ernest Darker, 26 SW!ln street Hoyle Thomas ••.••..•...•..••.•.• St. Michael's tJohn J,owry, Whol8l;ale Fish market, HiJi(h street JackJlon William Turnt>r...... •••. .• Harpurhey CRUMPSALL WARD. J ennison Angelo. ••• .. ••••••.•••.•.• Longsight Alderm.an. JohDBon James ••••••• '...... .•••.• St. Luke's J ohnston J a.me8.. .• •• •• •• •• •• •• •• .• Blackley and Moston IIEdward Holt, Derby Brewery, Cheetham J Olles John ••••••.••••••.••••••• I• Longsight Councillors. Jone8 John T •.•.. "' .....••.•..•.• New Cross tHarold Wood, The Wichnors, t3ingleton road, KerBal Kay William •....... _........... .• St. Georgc's -Frederick Todd, Waterloo st. Lower Crumpsall Kemp Jamea Miles Platting tFrederick John Robertshaw, Ivy House, Kea.rsley rd. Ol"llmpaall Kendall John James................ Oheetham DIDSBURY WARD. Lane-Scott William Fitzmaurtce.... Rusholrne Langley J ames Birchby •• ..•..••• •• St. Clement's AlcUrman. LecomtJer William Godfrey ••••••.• Medlock Street 11 WaIter Edward Harwood, 78 CrOSl! street Litton John George •• •••• .• •. •• .• •• St. Ann's Oouncillorl. Lofts John Albert................. -

A Sheffield Hallam University Thesis

Exploring the potential of complexity theory in urban regeneration processes. MOOBELA, Cletus. Available from the Sheffield Hallam University Research Archive (SHURA) at: http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20078/ A Sheffield Hallam University thesis This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Please visit http://shura.shu.ac.uk/20078/ and http://shura.shu.ac.uk/information.html for further details about copyright and re-use permissions. Fines are charged at 50p per hour JMUQ06 V-l 0 9 MAR ?R06 tjpnO - -a. t REFERENCE ProQuest Number: 10697385 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10697385 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Exploring the Potential of Complexity Theory in Urban Regeneration Processes Cletus Moobela A Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Sheffield Hallam University for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy July 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The carrying out and completion of this research project was a stimulating experience for me in an area that I have come to develop an ever-increasing amount of personal interest. -

For Sale / May Let 82,430 Sq Ft (7,657.94 Sq M) on a Site Area of Approx

For Sale / May Let 82,430 sq ft (7,657.94 sq m) On a site area of approx. 3 acres (1.214 hectares) • Located 3 miles from Manchester City Centre and 3½ miles from M60 Enter • Rare freehold opportunity Unit 3 Modern Self-Contained Warehouse / Industrial Facility Unit 3, Stainburn Road Openshaw, Manchester, M11 2DN Unit 3, Stainburn Road Openshaw, Manchester, M11 2DN FURTHER HOME LOCATION DESCRIPTION ACCOMMODATION GALLERY INFORMATION LOCATION Stainburn Road is located in the Openshaw area of Manchester within close proximity to Ashton Old Road (A635) and Alan Turing Way (A6010). Manchester City Centre is located 3 miles to the west while the M60 Motorway is 3.5 miles to the east accessed via the A635 Ashton Old Road. The M60 Orbital Motorway provides access to the national motorway network. Manchester Piccadilly Station 2.5 miles Stainburn Manchester City Centre 3 miles Road M60 Motorway 3.5 miles M67 Motorway 5.5 miles Manchester Airport 10 miles Modern Self-Contained Warehouse / Industrial Facility Unit 3, Stainburn Road Openshaw, Manchester, M11 2DN FURTHER HOME LOCATION DESCRIPTION ACCOMMODATION GALLERY INFORMATION Modern Self-Contained Warehouse / Industrial Facility Unit 3, Stainburn Road Openshaw, Manchester, M11 2DN FURTHER HOME LOCATION DESCRIPTION ACCOMMODATION GALLERY INFORMATION DESCRIPTION The property comprises a fully refurbished modern stand alone warehouse / industrial facility incorporating two storey office, car parking and sub station. It offers the following specification: Warehouse • Steel portal frame • PVC coated -

MANCHESTER, St Augustine [Formerly Granby Row, Later York

MM MAGHULL, St George; Archdiocese of Liverpool C 1887-1941 M 1880-1941 Copy reg Microfilm MF 9/126 MANCHESTER, All Saints see St Augustine MANCHESTER, St Augustine [formerly Granby Row, later York Street, now Grosvenor Square, All Saints]; Diocese of Salford C 1820-1826, 1856-1879 M 1837-1922 Orig reg RCMA 1889-1920 C 1820-1826, 1856-1900 M 1837-1900 Copy reg Microfilm MF 9/248-251 C 1870-1900 Copy reg Microfilm MF 1/203 C 1838-1900 Copy Microfilm MF 9/251 index C 1947-1962 M 1947-1954, 1961-1962 Reg rets RCSF 2 MANCHESTER, St Casimir (Oldham Road) see MANCHESTER, Collyhurst MANCHESTER, St Joseph (Goulden Street); Diocese of Salford [closed] C 1852-1903 M 1856-1904 Orig reg RCMJ C 1852-1903 M 1856-1904 Copy reg Microfilm MF 9/253-254 C 1873-1887 M 1885-1904 Copy reg Microfilm MF 1/243 C 1856-1903 Copy Microfilm MF 9/254 index For references in bold e.g. RCLN, please consult catalogues for individual register details and the full reference. For records in the Searchroom held on microfiche, microfilm or in printed or CRS format, please help yourself or consult a member of the Searchroom Team. 1 MM MANCHESTER, St Mary (Mulberry Street) [The Hidden Gem]; Diocese of Salford C 1794-1932 M 1837-1965 Orig reg RCMM C 1794-1922 M 1831-1903 B 1816-1825,1832-1837 Copy reg Microfilm MF 9/21-25 C 1947-1962 M 1947-1954, 1961-1962 Reg rets RCSF 2 C 1794-1819 B 1816-1825 Copy reg Microfilm DDX 241/24 C 1820-1831 Transcript CD Behind “Issue desk” in Searchroom C 1870-1941 M 1871-1941 Copy reg Microfilm MF 1/240-241 C 1850-1949 M 1837-1938 Copy Microfilm MF 9/25 index C 1870-1941 Index Microfilm MF 1/241 MANCHESTER, Livesey Street, see MANCHESTER, Collyhurst MANCHESTER, Ancoats, St Alban; Diocese of Salford [closed] C 1863-1960 M 1865-1959 D 1948-1960 Orig reg RCMN C 1863-1960 M 1865-1959 D 1948-1960 Copy reg MF 9/218-219 C 1947-1953, 1955-1960 M 1947-1954 Reg rets RCSF 2 C 1870-1941 M 1865-1941 Copy reg Microfilm MF 1/228-229 For references in bold e.g. -

Development Opportunities

DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITIES May 20120199 LAND AND BUILDINGS OFFERING DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL FOR SALE 2 Acres (0.8 Ha) MancheManchesterster City Centre DDevelopmentevelopment Opportunity Consent for 415 ApartApartmentsments Together with Commercial & Amenity SSpacepace Plus 153 Car Parking SSpacespaces North View, Dantzic Street, Manchester M4 4JE Planning consent has been granted for a single apaparartartartmentt ment building arranged around a central communcommunalal courtyard and which varies frofromm 5 to 24 storeys in height. The coconsentnsent provides for 130 one bed apartapartments,ments, 262 two bed, two bbathath apartmeapartmentsnts and 23 three bedbedbed,bed , three bath apartmentsapartments.. In additionaddition,,,, there is consent for 268m 222 of commercial space, car parking and public spacspacee including a residresidentententent’’’’ss gym. Further details araree available on thththeth e Me MaM aaanchesternchester Planning website, Planning Application No 114860/FO/2016.114860/FO/2016. A Section 106 Agreement has been completed. PPPrPrrrice:ice: The property is available £9.5millon. VAT will not apply to this transaction. SITE OF FORMER ALBERT & SUNNYSIDE MILLS MARKET STREET WHITWORTH LANCASHIRE RESIDENTIAL DEVELOPMENT SITE 3.5 ACRES Expected consent for 37 houses & 48 two bed apartments Attractive site in a pleasant residential setting Planning Application No 2018/0498 Rossendale Borough Council Asking Price £2million INTERESTING DEVELOPMENT/INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITY 2B STATION ROAD, NORTHWICH, CHESHIRE The property comprises a modern, single storey building comprising two retail units and which benefit from planning consent for the erection of an upper floor extension providing 5 self contained apartments. The first retail unit is let as a takeaway (lease expiring January 2027) at a rental of £12,000pa. The second unit is let to a bridal shop on a rolling licence at £10,000 per annum plus VAT. -

'What's on North'

‘What’s On North’ Newsletter November 2020 Get coronavirusCompiled support as an by extremely the Community vulnerable person Inclusion https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus Service - extremely-vulnerable Due to the Corona outbreak the What’s On newsletter is very different this month. A lot of activities have been cancelled until further notice. But here is some useful information and some fun and helpful things you could do while self-isolating. Stay alert We can all help control the virus if we all stay alert. This means you must: Stay at home as much as possible Work from home if you can Limit contact with other people Keep your distance from people not in your household (2 metres apart where possible) Wash your hands regularly Do not leave home if you or anyone in your household has symptoms. Please visit https://www.gov.uk/coronavirus for updates. Try to avoid speculation and look up reputable sources on the outbreak Rumour and speculation can fuel anxiety. Having access to good quality information about the virus can help you feel more in control. Check GOV.UK and https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/coronavirus-covid-19/ If news stories make you feel anxious or confused, think about switching off or limiting what you look at for a while. Social media could help you stay in touch with people, but might also make you feel anxious including if people are sharing news stories or posting about their worries. Consider taking a break or limiting how you use social media. You might decide to view particular groups or pages but not scroll through timelines or newsfeeds. -

The Manchester Red Eye Service

The Manchester Red Eye Service You can now get walk-in assessment and treatment for red, sore or itchy eyes through your local optometrist. What is the Red Eye Service? This is a free service available to all patients over the age of 12 years who are registered with a Manchester GP. The service provides a patient experiencing recently occurring red eye conditions with appropriate treatment closer to home or work. The service is provided by accredited optometrists (also known as opticians) with the specialist knowledge and skills to carry out this work at a local optometry practice. Eye conditions which can be treated in the Red Eye Service. The service is designed for recently occurring medical eye conditions such as: •Red eye/s or eyelids. •Significant recent discharge from or watering of the eye. •Irritation and inflammation of eye/s or eyelids. •Stye – infection at the edge of the eyelid. •Tear dysfunction – dry eye. If you are unsure whether your symptoms qualify, please contact one of the optometry practices who can advise you. How do I access the Red Eye Service? A list of practices providing the Service is enclosed with this leaflet. Please be aware that your normal optometry practice may have chosen not to offer this service. You can contact any of these practices directly (self-refer) to make an appointment and ask to be seen under the Red Eye Service. Appointments are available during normal working hours and you will be seen within 24 hours. Alternatively, your GP or other healthcare professional may refer you to the optometrist for treatment. -

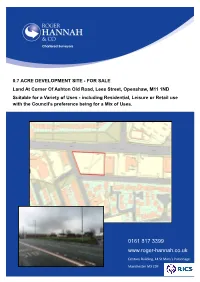

Insert Image Insert Image

0.7 ACRE DEVELOPMENT SITE - FOR SALE Land At Corner Of Ashton Old Road, Lees Street, Openshaw, M11 1ND Suitable for a Variety of Uses - including Residential, Leisure or Retail use with the Council’s preference being for a Mix of Uses. Insert Image Insert Image 0161 817 3399 www.roger-hannah.co.uk Century Building, 14 St Mary’s Parsonage Manchester M3 2DF LOCATION LOCATION PLAN The site is situated just over 1.5 miles east of Manchester City Centre on the edge of Openshaw District Centre on Ashton Old Road, a major arterial route into Manchester. The site is conveniently situated on the edge of the District Centre, which has benefitted from significant investment in the last 5 years. This includes the development of a new Morrisons store, shops, medical centre, gym and food and drink outlets, a new primary school to the west, a facelift scheme to stores in the District Centre and improvements to the highway and pedestrian environment. The area to the south is predominantly residential and new housing developments have been completed at Ogden Lane, Cornwall Street, Varna Street and Constable Street. New housing developments have also been completed at Toxteth Street and Louisa Street. DESCRIPTION We are advised that all mains services are available to the site. The site is bounded by Lees Street to the west, Stanley Street TENURE to the south and a Halfords MOT garage to the east. The site is mainly rectangular in shape with one distinctive triangular We are advised the site is freehold corner fronting Ashton Old Road and Lees Street. -

5JAN201722042080 January 26, 2018

5JAN201722042080 January 26, 2018 To My Fellow Stockholders: After a challenging fiscal 2017 characterized by competitive pricing and low volume in some of our key markets, order entry has gained momentum through the beginning of fiscal 2018. We are hopeful that this is indicative of returning strength in our end markets. Aerospace, buoyed by the ramp-up of the new engine platforms, along with better activity in chemical processing special projects, are leading the way at this point, and we expect these markets, along with our tolling business and smaller industrial markets like heat treating and energy, to continue to expand as we move deeper into 2018. During fiscal 2017 and early fiscal 2018, we completed our major capital expenditure projects. During this cycle, we rebuilt, expanded, and improved our operating facilities and capabilities. Supporting our growth in aerospace, we upgraded and expanded our tubular products facilities, allowing us to ship a record volume of tubular products in 2017. In our flat roll operations, we have completed our capital investments in heat-treating, rolling and shape correction operations, particularly a significant expansion in our cold-rolling and finishing capabilities, which is expected to help us meet increasing demand in the aerospace market. We also completed the implementation of our new global IT system, migrating a myriad of discrete systems into a single, global operating platform enhancing our ability to monitor and optimize worldwide manufacturing and distribution operations. Supporting our service and value-added operations, we expanded our operations in LaPorte, Indiana and Openshaw, England in order to more efficiently meet the needs of our key markets. -

Constitutional and Nomination Committee – 12 March 2021 Subject

Manchester City Council Report for Resolution Report to: Constitutional and Nomination Committee – 12 March 2021 Subject: Proposed Redesignation of Polling Places for 6 May 2021 Elections Report of: The Chief Executive Summary To propose changes to the current scheme of polling places for the following wards: Crumpsall (1CRG), Harpurhey (1HAG), Clayton & Openshaw (polling district 2COF), Piccadilly (polling districts 2PYB, 2PYC/2PYE), Whalley Range (polling district 3WRD), Baguley (polling districts 5BAB and 5BAF), Brooklands/Northenden (polling districts 5BKF/5NOA), Sharston (5SHB) and Woodhouse Park (polling district 5WPA). Recommendations 1. To approve the proposed changes to the current scheme as set out in Sections 4 to 8. 2. To recommend that the changes to the polling places are adopted in relation to both parliamentary and local government elections. 3. To note that an update on the current position regarding outstanding re- designations for polling places referred to in this report, but not resolved at time of publication, will be brought to the meeting for the Committee’s consideration. 4. To recommend that any emerging polling place re-designations required ahead of 6 May 2021 elections, which cannot be reported to the Committee on 12 March 2021, are agreed using the delegated authority of the Chief Executive, which allows her to make, where necessary, alterations to the designation of any polling place prior to the next full review in consultation with ward councillors, group leaders and the Chair of Constitutional and Nomination Committee. Wards Affected: Crumpsall, Harpurhey, Clayton & Openshaw, Piccadilly, Whalley Range, Baguley, Brooklands, Northenden, Sharston and Woodhouse Park. Alignment to the Our Manchester Strategy Outcomes (if applicable) Manchester Strategy outcomes Summary of how this report aligns to the OMS A thriving and sustainable city: supporting a diverse and distinctive economy that creates jobs and opportunities The Our Manchester Strategy sets out the vision for the city to 2025. -

Didsbury Manchester M20 6Qz

651-653B WILMSLOW ROAD DIDSBURY MANCHESTER M20 6QZ FULLY LET RETAIL & LEISURE PARADE INVESTMENT UNEXPIRED LEASE TERM 0F 12.1 YEARS, 15.7 YEARS TO EXPIRY 651-653B WILMSLOW ROAD DIDSBURY MANCHESTER M20 6QZ INVESTMENT CONSIDERATIONS PROPOSAL ■ Didsbury is an affluent and highly ■ Tesco and Stonegate Pub Company ■ Freehold ■ We are instructed to seek offers in desirable suburb of Manchester t/a Slug and Lettuce have been ■ Car parking to the rear of the site excess of £5,500,000 (Five Million, ■ Popular retail and leisure parade in occupation since 1998 let on a management agreement, Five hundred Thousand Pounds) in the heart of Didsbury Village ■ Attractive AWULT of 12.1 years terminable by either party on subject to contract and exclusive of VAT. This equates to an attractive ■ to break, 15.7 years to expiry 3 months’ notice Fully let to 5 tenants including net initial yield of 7.21% assuming a mix of national and independent ■ Total passing rent of £422,750 ■ Total site area of 1.04 acres purchaser’s costs of 6.61% operators benefiting from a diverse per annum reflecting £25 psf ■ Strong residential values, potential income stream ■ Total floor area of16,977 sq ft to convert the upper parts subject arranged over ground and first floor to planning 651-653B WILMSLOW ROAD S m ed le y R DIDSBURY o a A d 60 AD MANCHESTER M20 6QZ 10 M RO ad A o H 76 D A56 rloo R e OL t A5 a COLLYHURST W A5066 d A62 a e an Ro L e e o l risc 186 da B h B6 c o STRANGEWAYS R SALFORD M60 CRESCENT ad Ro rd fo A d SALFORD 042MANCHESTER ra A B 6 601 6 A VICTORIA A SALFORD -

GMPR11 Ashburys

Foreword • Contents Some of this country’s most significant nineteenth • and early twentieth century industrial enterprises Introduction .......................................................2 have disappeared leaving surprisingly little The Historic Setting ...........................................6 surviving evidence. This booklet highlights the 19th Century Industrialisation ..........................8 work undertaken as part of recent archaeological investigations looking at two adjoining areas of John Ashbury: The Early Years ...................... 10 the former Ashbury’s Carriage and Iron Works, Ashbury’s In Openshaw 1847-1928 ................. 12 Openshaw, Manchester. Established in 1847, Excavation Of The Foundry ............................22 Ashbury’s grew to be a major supplier both to Products Of The Ashbury Works .....................36 domestic and global markets of iron, steel, rolling stock and railway components. Apart from the Working At The Plant ......................................42 Ashbury’s railway station little or no visible Further Investigation ......................................44 surface evidence survives today of where the Glossary ...........................................................47 works once stood. The company’s archives also Further Reading ..............................................48 appear not to have survived. Acknowledgements ..........................................49 The fragmentary cartographic, documentary and photographic evidence for the history and development of Ashbury’s