Appendices and Glossary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Important Notice This Base Prospectus Is Available

IMPORTANT NOTICE THIS BASE PROSPECTUS IS AVAILABLE ONLY TO INVESTORS WHO ARE NOT US PERSONS (AS DEFINED IN REGULATION S ("REGULATION S") UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT OF 1933, AS AMENDED (THE "SECURITIES ACT") LOCATED OUTSIDE THE UNITED STATES IN ACCORDANCE WITH REGULATION S. IMPORTANT: You must read the following before continuing. The following applies to the Base Prospectus following this page whether received by email, accessed from an internet page or otherwise received as a result of electronic communication, and you are therefore advised to read this page carefully before reading, accessing or making any other use of the Base Prospectus. In reading, accessing or making any other use of the Base Prospectus, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions and each of the restrictions set out in the Base Prospectus, including any modifications to them from time to time each time you receive any information from the Issuer, the Guarantor, the Arrangers or the Dealers, (each as defined in the Base Prospectus) as a result of such access. NOTHING IN THIS ELECTRONIC TRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES AN OFFER OF SECURITIES FOR SALE OR A SOLICITATION OF AN OFFER TO BUY THE NOTES IN THE UNITED STATES OR ANY OTHER JURISDICTION WHERE IT IS UNLAWFUL TO DO SO. THE NOTES HAVE NOT BEEN, AND WILL NOT BE, REGISTERED UNDER THE SECURITIES ACT, OR THE SECURITIES LAWS OF ANY STATE OF THE UNITED STATES OR OTHER JURISDICTION, AND THE NOTES MAY NOT BE OFFERED OR SOLD, DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY, WITHIN THE UNITED STATES OR TO, OR FOR THE ACCOUNT OR BENEFIT OF, US PERSONS (AS DEFINED IN REGULATION S) EXCEPT PURSUANT TO AN EXEMPTION FROM, OR IN A TRANSACTION NOT SUBJECT TO, THE REGISTRATION REQUIREMENTS OF THE SECURITIES ACT AND APPLICABLE STATE OR LOCAL SECURITIES LAWS. -

Securities and Exchange Commission on September 29, 2004

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on September 29, 2004 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 ——————— FORM 20-F REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ⌧ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended: March 31, 2004 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 0-29304 (Commission file number) Ryanair Holdings plc (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Ryanair Holdings plc (Translation of registrant’s name into English) Republic of Ireland (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) c/o Ryanair Limited Corporate Head Office Dublin Airport County Dublin, Ireland (Address of principal executive offices) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. None Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each national market on which registered American Depositary Shares, each Nasdaq National Market representing five Ordinary Shares Ordinary Shares, par value Nasdaq National Market* 1.27 euro cent per Share Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. 759,271,140 Ordinary Shares Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

20F Statement 2020

As filed with the United States Securities and Exchange Commission on July 28, 2020 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F ☐ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended: March 31, 2020 OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ☐ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT/ TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report:___________ For the transition period from _________ to _________ Commission file number: 000-29304 Ryanair Holdings plc (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Ryanair Holdings plc (Translation of registrant’s name into English) Republic of Ireland (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) c/o Ryanair DAC Dublin Office Airside Business Park, Swords County Dublin, K67 NY94, Ireland (Address of principal executive offices) Please see “Item 4. Information on the Company” herein. (Name, telephone, e-mail and/or facsimile number and address of company contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. Title of each class Trading Symbol(s) Name of each exchange on which registered American Depositary Shares, each representing RYAAY The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC five Ordinary Shares Ordinary Shares, par value 0.6 euro cent per share RYAAY The NASDAQ Stock Market LLC (not for trading but only in connection with the registration of the American Depositary Shares) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the Annual Report. -

World Air Transport Statistics, Media Kit Edition 2021

Since 1949 + WATSWorld Air Transport Statistics 2021 NOTICE DISCLAIMER. The information contained in this publication is subject to constant review in the light of changing government requirements and regulations. No subscriber or other reader should act on the basis of any such information without referring to applicable laws and regulations and/ or without taking appropriate professional advice. Although every effort has been made to ensure accuracy, the International Air Transport Associ- ation shall not be held responsible for any loss or damage caused by errors, omissions, misprints or misinterpretation of the contents hereof. Fur- thermore, the International Air Transport Asso- ciation expressly disclaims any and all liability to any person or entity, whether a purchaser of this publication or not, in respect of anything done or omitted, and the consequences of anything done or omitted, by any such person or entity in reliance on the contents of this publication. Opinions expressed in advertisements ap- pearing in this publication are the advertiser’s opinions and do not necessarily reflect those of IATA. The mention of specific companies or products in advertisement does not im- ply that they are endorsed or recommended by IATA in preference to others of a similar na- ture which are not mentioned or advertised. © International Air Transport Association. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, recast, reformatted or trans- mitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval sys- tem, without the prior written permission from: Deputy Director General International Air Transport Association 33, Route de l’Aéroport 1215 Geneva 15 Airport Switzerland World Air Transport Statistics, Plus Edition 2021 ISBN 978-92-9264-350-8 © 2021 International Air Transport Association. -

20F 2002 Main.Pdf

As filed with the Securities and Exchange Commission on September 30, 2002 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20549 ——————— FORM 20-F ¨ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR x ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Fiscal Year Ended: March 31, 2002 0-29304 (Commission file number) Ryanair Holdings plc (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Ryanair Holdings plc (Translation of registrant’s name into English) Republic of Ireland (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) c/o Ryanair Limited Corporate Head Office Dublin Airport County Dublin, Ireland (Address of principal executive offices) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act. None Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Title of each class Name of each national market on which registered American Depositary Shares, each Nasdaq National Market representing five Ordinary Shares Ordinary Shares, par value Nasdaq National Market* 1.27 euro cents per Share Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None (Title of Class) Indicate the number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of the close of the period covered by the annual report. 755,030,716 Ordinary Shares Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Page Contents

Other PAGEOther CONTENTS assets 2 Financial Summary 3 Key Statistics 4 Chairman’s Report 6 Group Chief Executive’s Report 11 Directors’ Report 15 Corporate Governance Report 30 Environmental and Social Report 37 Report of the Remuneration Committee on Directors’ Remuneration 41 Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 43 Independent Auditor’s Report 48 Presentation of Financial and Certain Other Information 50 Detailed Index* 53 Key Information 59 Principal Risks and Uncertainties 73 Information on the Company 96 Operating and Financial Review 99 Critical Accounting Policies 111 Directors, Senior Management and Employees 119 Major Shareholders and Related Party Transactions 120 Financial Information 126 Additional Information 137 Quantitative and Qualitative Disclosures About Market Risk 142 Controls and Procedures 145 Consolidated Financial Statements 196 Company Financial Statements 202 Directors and Other Information 203 Appendix *See Index on page 50 to 52 for detailed table of contents. Information on the Company is available online via the internet at our website, http://corporate.ryanair.com. Information on our website does not constitute part of this Annual Report. This Annual Report and our 20-F are available on our website. 1 2 3 Chairman’s Report Dear Shareholders, Last year we made significant progress in growing Ryanair as Europe’s largest airline group. We aim to carry 200m guests per annum over the next 5 years. Highlights of the year include: • Traffic grew 9% to over 142m guests • Avg. air fares were cut 6% to €37 • Revenue -

Strategic Analysis of Ryanair

Strategic analysis of Ryanair Master’s Thesis Copenhagen Business School January 13th 2020 Program: MSc. International Business Author: George-Cristian Prichinet Supervisor: Number of standard pages: 78 Niels Le Duc Number of characters: 156,343 Executive Summary During the past decades, Ryanair’s strategies and continuous growth have successfully turned the company from a single route airline into the largest low cost carrier in Europe. However, Ryanair is currently facing a major disruption: Brexit. United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union has created a great wave of uncertainty that is set to also impact the airline industry. With 30% of its revenues coming from flights within and connecting the United Kingdom, Ryanair is now facing a series of decision that need to be taken in order to ensure a smooth transition after Brexit. The scope of this thesis is to provide Ryanair with a number of strategic options that could help it adapt to the impact of Brexit. In this regards, an in depth strategic analysis is conducted, with the results serving as a knowledge base for a scenario planning analysis. The scenarios developed are to present the issues Ryanair might encounter in different situations and it is on these issues that the strategic recommendations are based on. The thesis mainly consists of three main parts: Company Overview, Strategic analysis of Ryanair and Scenario planning, with the latter being the main focus of the thesis. The Company overview presents and analyzes the history of Ryanair, its corporate structure and governance, its vision and mission alongside its business model and its competitors. -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „The Impact of Atypical Employment on Job Satisfaction of Airline Pilots“ verfasst von / submitted by Vera Katharina Valeria Bönnemann, BA BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) Wien, 2019 / Vienna 2019 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / UA 066 914 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Internationale Betriebswirtschaft degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Oliver Fabel, M.A. Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides Statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirekt übernommenen Gedanken sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und auch noch nicht veröffentlicht. Statutory Declaration I hereby declare that I have written the present thesis independently and without the aid of unfair or unauthorized resources. Whenever content was taken directly or indirectly from other sources, this has been indicated and the source referenced. This thesis has neither previously been presented for assessment, nor has it been published. Table of Contents List of abbreviations ........................................................................................................ -

Consolidation of Airlines in Europe. Potential Acquisition of Norwegian by Easyjet

Consolidation of airlines in Europe. Potential acquisition of Norwegian by EasyJet Dmitrii Ponomarev Dissertation written under the supervision of António Borges de Assunção Dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the MSc in Finance, at the Universidade Católica Portuguesa, June 2020. Abstract Europe is one of the largest airline markets with a significant share of passengers withing Europe being flown by low-cost carriers, while long-haul passengers are almost entirely transported by traditional flag carriers. While Full-Service airlines have been actively trying to penetrate the low-cost market, Norwegian and some other LCCs entered the long-haul market. As this industry is risky and capital extensive, while also being highly competitive, we may expect a consolidation of European airlines. A merger between the second-largest low-cost carrier in Europe EasyJet and smaller but operating rather unique business model Norwegian would allow a boost of passengers for both airlines, open new markets, and deliver significant revenue and cost synergies especially on the side of struggling to fill their planes and maintain its margins Norwegian, and would create a new second-largest airline in Europe. We expect a transaction between two Airlines to happen in the last quarter of 2020, EasyJet is suggested to pay the premium of 20% over the market price, the total purchase would cost ₤1040m and generate ₤524m in Net Synergies after transaction costs. Suggested financing assumes using existing cash, debt, and stock issuance. The industry is highly dependent on the developments related to the COVID-19 outbreak, therefore we suggest constant revaluation of the deal as long as the new information appears. -

Air Y Rkshire

AIRAIR YY RKSHIRERKSHIRE AviationAviation SocietySociety Volume 45 · Issue 4 April 2019 ZM413ZM413 RAFRAF AtlasAtlas 400M400M LeedsLeeds BradfordBradford AirportAirport 1616 FebruaryFebruary 20192019 JimJim StanfieldStanfield www.airyorkshire.org.uk Monthly meetings/presentations.... The Media Centre, Leeds Bradford Airport Tuesday 7 May 2019 @ 7pm Steven Small – Brand Director, Routes Organisation. Steven will give us in insight into the ROUTES business which is focused entirely on aviation route development and the company's portfolio includes events, media and online businesses. Routes events are a source of breaking news in the aviation industry. Announcements about new air services are frequently made at the events, and the high profile discussions at the conference frequently hit the headlines. 2 June 2019 @ Dave Ward - Fun in Flight Test. Partly humorous overview of his career, mainly in the 2.30pm Flight Test Department at BAe Warton. It includes some detail of why we have a Flight Test Department at all and how it works. 7 July 2019 @ Aldon Ferguson – We welcome back Aldon to Air Yorkshire. This time Aldon will be 2.30pm presenting his in depth study of Church Fenton with many photos, both old and new. Aldon is a very experienced speaker with an excellent presentation style. Society news.... Alan Sinfield Photographs from Leeds Bradford Airport – You will notice that there are only two photographs of commercial aircraft in the LBA Airline Movements section. The reason for this is that I only received these two photographs. I am sure more photographs have been taken by members who don't normally send them in. If you are unsure how to provide photographs please ask me! Murgatroyd's Fish & Chip Lunch - The next one is on Saturday 11th May 2019 at 1200. -

Communications Department External Information Services 16 May 2018

Communications Department External Information Services 16 May 2018 Reference: F0003681 Dear I am writing in respect of your amended request of 17 April 2018, for the release of information held by the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA). You requested data on Air Operator Certificate (AOC) holders, specifically a complete list of AOC numbers and the name of the company to which they were issued. Having considered your request in line with the provisions of the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA), we are able to provide the information attached. The list includes all the AOC holder details we still hold. While it does include some historical information it is not a complete historical list, and the name of the AOC holder is not necessarily the name of the organisation at the time the AOC was issued. If you are not satisfied with how we have dealt with your request in the first instance you should approach the CAA in writing at:- Caroline Chalk Head of External Information Services Civil Aviation Authority Aviation House Gatwick Airport South Gatwick RH6 0YR [email protected] The CAA has a formal internal review process for dealing with appeals or complaints in connection with Freedom of Information requests. The key steps in this process are set in the attachment. Civil Aviation Authority Aviation House Gatwick Airport South Gatwick RH6 0YR. www.caa.co.uk Telephone: 01293 768512. [email protected] Page 2 Should you remain dissatisfied with the outcome you have a right under Section 50 of the FOIA to appeal against the decision by contacting the Information Commissioner at:- Information Commissioner’s Office FOI/EIR Complaints Resolution Wycliffe House Water Lane Wilmslow SK9 5AF https://ico.org.uk/concerns/ If you wish to request further information from the CAA, please use the form on the CAA website at http://publicapps.caa.co.uk/modalapplication.aspx?appid=24. -

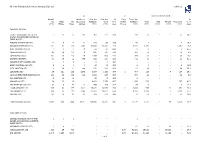

Table 05 All Non Scheduled Services

All Non-Scheduled Services January 2021 (a) Table 5.1 (b) (b) Tonne-Kilometres Used Aircraft Number of Seat-Km Seat-Km As Cargo Tonne-Km As -Km Stage A/C Passengers Available Used % of Uplifted Available Total Mail Freight Passenger % of (000) Flights Hours Uplifted (000) (000) Avail Tonnes (000) (000) (000) (000) (000) Avail Passenger Services 2 EXCEL AVIATION LTD T/A THE 7 12 12 411 364 217 59.6 - 60 22 - - 22 36.7 BLADES BROADSWORD SCIMITAR SABRE AND T2 ACROPOLIS AVIATION LTD 12 3 14 20 226 85 37.6 - 42 7 - - 7 16.7 AIRTANKER SERVICES LTD 227 40 303 1,863 63,928 13,461 21.1 - 9,247 1,260 - - 1,260 13.6 BLUE ISLANDS LIMITED 1 2 2 91 56 37 66.1 - 5 3 - - 3 60.0 CATREUS AOC LTD 83 28 110 46 942 281 29.8 - 282 28 - - 28 9.9 CONCIERGE U LTD 107 16 132 99 1,493 662 44.3 - 309 51 - - 51 16.5 EASTERN AIRWAYS 10 29 22 948 625 330 52.8 - 62 33 - - 33 53.2 EXECUTIVE JET CHARTER LTD - 1 1 2 6 1 16.7 - - - - - - - GAMA AVIATION (UK) LTD 4 2 6 6 37 13 35.1 - 8 1 - - 1 12.5 JOTA AVIATION LTD 6 24 15 988 532 228 42.9 - 51 19 - - 19 37.3 LOGANAIR LTD 89 251 261 2,546 3,884 1,335 34.4 10 407 118 - 4 114 29.0 LONDON EXECUTIVE AVIATION LTD 110 38 151 128 1,364 486 35.6 - 507 48 - - 48 9.5 RVL AVIATION LTD 4 11 11 - 27 5 18.5 - 6 - - - - - RYANAIR UK LTD 34 22 55 - 6,412 3,763 58.7 - 695 297 - - 297 42.7 TAG AVIATION (UK) LTD 32 9 40 22 469 105 22.4 - 84 9 - - 9 10.7 TITAN AIRWAYS LTD 209 67 293 2,119 36,276 10,539 29.1 11 3,086 938 - 41 897 30.4 TUI AIRWAYS LTD 148 40 194 4,065 42,124 25,511 60.6 1 6,247 2,315 - 4 2,311 37.1 VOLUXIS LTD 51 13 64 60 701