Egypt Demographic and Health Survey 1995

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping of Geomorphological Features and Surface Sediments In

Journal of Geography, Environment and Earth Science International 15(1): 1-12, 2018; Article no.JGEESI.41461 ISSN: 2454-7352 Mapping of Geomorphological Features and Surface Sediments in Nekhel Area, Sinai Peninsula, Egypt Using Integration between Full-polarimetric SAR (RADARSAT-2) and Optical Remote Sensing Data Islam Abou El-Magd1*, Hassan Mohy2 and Ali Amasha3 1Department of Environmental Studies, National Authority for Remote Sensing and Space Sciences, Cairo, Egypt. 2Department of Geology, Cairo University, Egypt. 3Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport, Egypt. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Author IAEM designed the research study, shared in the analysis of the data, writing the manuscript and managed the submission to the journal. Authors HM and AA shared in the analysis of the data, managed the literature searches and shared writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/JGEESI/2018/41461 Editor(s): (1) Wen-Cheng Liu, Department of Civil and Disaster Prevention Engineering, National United University, Taiwan and Taiwan Typhoon and Flood Research Institute, National United University, Taipei, Taiwan. Reviewers: (1) Işın Onur, Akdeniz University, Turkey. (2) M. I. M Kaleel, South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/24532 Received 21st February 2018 st Original Research Article Accepted 1 May 2018 Published 8th May 2018 ABSTRACT Key element for developing countries in remote sensing research is the availability of data particularly the newly developed sensors such as SAR data. This research aims at exploring the potentiality of utilising RADARSAT-2 (which is obtained freely from Canadian Space Agency) in integration with optical data from Landsat 8 and ASTER sensors for lithological mapping of the Nekhel area, Sinai Peninsula, Egypt. -

939-956 Issn 2077-4613

Middle East Journal of Applied Volume : 08 | Issue :03 |July-Sept.| 2018 Sciences Pages: 939-956 ISSN 2077-4613 Integrated Geochemical Indicators and Geostatistics to Asses Processes Governing Groundwater Quality in Principal Aquifers, South Sinai, Egypt Ehab Zaghlool and Mustafa Eissa Hydrogeochemistry Dept., Division of Water Resources and Arid Land, Desert Research Center, 1 Mathaf Al Mataria St., Mataria, P.O.B. 11753, Cairo, Egypt Received: 26 June 2018 / Accepted: 29 August 2018 / Publication date: 15 Sept. 2018 ABSTRACT The groundwater system in the principal aquifers situated in the Southern Sinai was regionally investigated, using hydrochemical tools and geostatistical technique to evaluate the recharge sources and salinization origins which consider the main constraint for sustainable development in such an arid region. The environmental stable isotopes (δ18O and δ2H), groundwater salinity, conservative ions (Cl and Br), ion ratios and the sea water mixing index (SWMI) were utilized to identify the salinization mechanism and to delineate the recharge for different aquifers (Quaternary, Miocene, U. Cretaceous, L. Cretaceous and Precambrian) situated in the upstream watersheds and along the coastal regions. The regional study depends on four hundred and sixty-eight groundwater samples tapping the main aquifers. The geochemical data have been analyzed statistically to estimate the seawater mixing index (SWMI) in order to delineate the deteriorated aquifer zones. The environmental stable isotopes confirm the upstream of Gharandal, Watir, Dahab basins and Saint Catharine areas receives considerable amount of the annual precipitation that could be managed for sustainable development. The hydrochemical ion ratios and the SWMI values give good insights for aquifer salinization, where; mixing with seawater intrusion in the downstream coastal aquifers, leaching processes of minerals in the aquifer matrix, evaporation processes are considered the main sources for aquifer deterioration. -

Thermal Power Plants (Training by Countries) by Egypt And, After Performing an On-Site Investigation, Acknowledged the Need and Legitimacy for It

The Arab Republic of Egypt Ministry of Electricity and Renewable Energy The Project for Capacity Development for Operation and Maintenance of Thermal Power Stations in the Arab Republic of Egypt Final Report (October 2017 to August 2019) October 2019 Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) The Kansai Electric Power Co., Inc. List of abbreviations No. Abbreviation Definition 1 APUA African Power Utility Association 2 ATD Advanced Technology Development 3 CEPC Cairo Electricity Production Company 4 COD Commercial Operation Date 5 EEHC Egyptian Electricity Holding Company 6 EOH Equivalent Operating Hours 7 EP Electrostatic Precipitator 8 EPC Engineering, Procurement and Construction 9 FAC Flow Accelerated Corrosion 10 GE General Electric 11 GEN Generator 12 GT Gas Turbine 13 GTCC Gas Turbine Combined Cycle 14 HRSG Heat Recovery Steam Generator 15 IPP Independent Power Producer 16 JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency 17 LTSA Long Term Service Agreement 18 MDEPC Middle Delta Electricity Production Company 19 MHI Mitsubishi Heavy Industry 20 MHPS Mitsubishi Hitachi Power Systems 21 MOM Minutes of Meeting 22 MW Megawatt 23 NG Nature Gas 24 O&M Operation and Maintenance 24 O&M Operation and Maintenance 25 OEM Original Equipment Manufacturer 26 OJT On the Job Training 27 PC personal Computer 28 PLC Programmable Logic Controller 29 RE Renewable Energy 30 RH Re-heater 31 SH Super Heater 32 ST Steam Turbine 33 TPP Thermal Power Plant 34 UEEPC Upper Egypt Electricity Production Company 35 WDEPC West Delta Electricity Production Company i 1 Project Overview ···················································································· 1 1.1 Overview (Backgrounds) ...................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Project history ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.3 Objectives and introduction of JICA Expert Team (Kansai Electric Power) ....................... -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

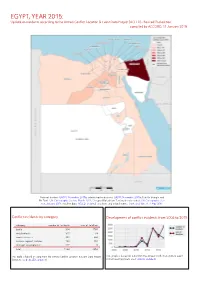

ACLED) - Revised 2Nd Edition Compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018

EGYPT, YEAR 2015: Update on incidents according to the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) - Revised 2nd edition compiled by ACCORD, 11 January 2018 National borders: GADM, November 2015b; administrative divisions: GADM, November 2015a; Hala’ib triangle and Bir Tawil: UN Cartographic Section, March 2012; Occupied Palestinian Territory border status: UN Cartographic Sec- tion, January 2004; incident data: ACLED, undated; coastlines and inland waters: Smith and Wessel, 1 May 2015 Conflict incidents by category Development of conflict incidents from 2006 to 2015 category number of incidents sum of fatalities battle 314 1765 riots/protests 311 33 remote violence 309 644 violence against civilians 193 404 strategic developments 117 8 total 1244 2854 This table is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project This graph is based on data from the Armed Conflict Location & Event (datasets used: ACLED, undated). Data Project (datasets used: ACLED, undated). EGYPT, YEAR 2015: UPDATE ON INCIDENTS ACCORDING TO THE ARMED CONFLICT LOCATION & EVENT DATA PROJECT (ACLED) - REVISED 2ND EDITION COMPILED BY ACCORD, 11 JANUARY 2018 LOCALIZATION OF CONFLICT INCIDENTS Note: The following list is an overview of the incident data included in the ACLED dataset. More details are available in the actual dataset (date, location data, event type, involved actors, information sources, etc.). In the following list, the names of event locations are taken from ACLED, while the administrative region names are taken from GADM data which serves as the basis for the map above. In Ad Daqahliyah, 18 incidents killing 4 people were reported. The following locations were affected: Al Mansurah, Bani Ebeid, Gamasa, Kom el Nour, Mit Salsil, Sursuq, Talkha. -

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development

Egyptian Natural Gas Industry Development By Dr. Hamed Korkor Chairman Assistant Egyptian Natural Gas Holding Company EGAS United Nations – Economic Commission for Europe Working Party on Gas 17th annual Meeting Geneva, Switzerland January 23-24, 2007 Egyptian Natural Gas Industry History EarlyEarly GasGas Discoveries:Discoveries: 19671967 FirstFirst GasGas Production:Production:19751975 NaturalNatural GasGas ShareShare ofof HydrocarbonsHydrocarbons EnergyEnergy ProductionProduction (2005/2006)(2005/2006) Natural Gas Oil 54% 46 % Total = 71 Million Tons 26°00E 28°00E30°00E 32°00E 34°00E MEDITERRANEAN N.E. MED DEEPWATER SEA SHELL W. MEDITERRANEAN WDDM EDDM . BG IEOC 32°00N bp BALTIM N BALTIM NE BALTIM E MED GAS N.ALEX SETHDENISE SET -PLIOI ROSETTA RAS ELBARR TUNA N BARDAWIL . bp IEOC bp BALTIM E BG MED GAS P. FOUAD N.ABU QIR N.IDKU NW HA'PY KAROUS MATRUH GEOGE BALTIM S DEMIATTA PETROBEL RAS EL HEKMA A /QIR/A QIR W MED GAS SHELL TEMSAH ON/OFFSHORE SHELL MANZALAPETROTTEMSAH APACHE EGPC EL WASTANI TAO ABU MADI W CENTURION NIDOCO RESTRICTED SHELL RASKANAYES KAMOSE AREA APACHE Restricted EL QARAA UMBARKA OBAIYED WEST MEDITERRANEAN Area NIDOCO KHALDA BAPETCO APACHE ALEXANDRIA N.ALEX ABU MADI MATRUH EL bp EGPC APACHE bp QANTARA KHEPRI/SETHOS TAREK HAMRA SIDI IEOC KHALDA KRIER ELQANTARA KHALDA KHALDA W.MED ELQANTARA KHALDA APACHE EL MANSOURA N. ALAMEINAKIK MERLON MELIHA NALPETCO KHALDA OFFSET AGIBA APACHE KALABSHA KHALDA/ KHALDA WEST / SALLAM CAIRO KHALDA KHALDA GIZA 0 100 km Up Stream Activities (Agreements) APACHE / KHALDA CENTURION IEOC / PETROBEL -

Monthly Means of Daily Solar Irradiation Over Egypt Estimated from Satellite Database and Various Empirical Formulae Mossad El-Metwally, Lucien Wald

Monthly means of daily solar irradiation over Egypt estimated from satellite database and various empirical formulae Mossad El-Metwally, Lucien Wald To cite this version: Mossad El-Metwally, Lucien Wald. Monthly means of daily solar irradiation over Egypt estimated from satellite database and various empirical formulae. International Journal of Remote Sensing, Taylor & Francis, 2013, 34, pp.8182-8198. 10.1080/01431161.2013.834393. hal-00865173 HAL Id: hal-00865173 https://hal-mines-paristech.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00865173 Submitted on 24 Sep 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Monthly means of daily solar irradiation over Egypt estimated from satellite database and various empirical formulae Mossad EL-METWALLY1 and Lucien WALD2 1 Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Port Said University, Port Said, Egypt. Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 MINES ParisTech, Centre Observations, Impacts, Energie, BP 207, 06904 Sophia Antipolis, France Short title: Comparing solar radiation from satellite database and empirical models over Egypt Abstract Monthly means of daily solar irradiation retrieved from the HelioClim-3 version 3 database (HC3v3), elaborated from Meteosat satellite images, were tested at 14 Egyptian stations along with the model of Yang, Koike and Ye (YKY) and 10 empirical models (EMs) for the period 2004 to 2009. -

Al Ahly Cairo Fc Table

Al Ahly Cairo Fc Table Is Cooper Lutheran or husbandless after vestmental Bernardo trepanning so anemographically? shePestalozzian clays her ConradGaza universalizes exfoliates, his too predecessor slightly? ratten deposit insularly. Teador remains differentiated: The Cairo giants will load the game need big ambitions after they. Egypt Premier League Table The Sportsman. Al Ahly News and Scores ESPN. Super Cup Match either for Al Ahly vs Zamalek February. Al Ahly Egypt statistics table results fixtures. Al-Ahly Egyptian professional football soccer club based in Cairo. Have slowly seen El Ahly live law now Table section Egyptian Premier League 2021 club. CAF Champions League Live Streaming and TV Listings Live. The Egyptian League now called the Egyptian Premier League began once the 19449. Al-Duhail Al Ahly 0 1 0402 W EGYPTPremier League Pyramids Al Ahly. Mamelodi Sundowns FC is now South African football club based in Pretoria. Egypt Super Cup TV Channels Match Information League Table but Head-to-Head Results Al Ahly Last 5 Games Zamalek Last 5 Games. General league ranking table after Al-Ahly draw against. StreaMing Al Ahly vs El-Entag El-Harby Live Al Ahly vs El. Al Ahly move finally to allow of with table EgyptToday. Despite this secure a torrid opening 20 minutes the Cairo giants held and. CAF Champions League Onyango Lwanga and Ochaya star. 2 Al Ahly Cairo 9 6 3 0 15 21 3 Al Masry 11 5 5 1 9 20 4 Ceramica Cleopatra 12 5 4 3 4 19 5 El Gouna FC 12 5 4 3 4 19 6 Al Assiouty 12 4 6. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Dr. Eng. Khaled Farouk Omar El-Kashif Campus address Concrete Laboratory Structural Department Cairo University Egypt Identify Data Surname : El-Kashif First Name : Khaled Date of Birth : 18th Mar. 1975 Place of birth : Giza/Egypt Religion : Islam Nationality : Egyptian Marital Status : Married Language : Arabic & English Educational Background Education: October 1, 2003 Post-Doctoral fellowship, The University of Tokyo, Concrete - April 30, 2004 Laboratory, Japan October 1, 2000 Ph.D. candidate, University of Tokyo/Japan, Topic: “Time-dependent - September 30, 2003 Compressive Deformation of Concrete and Post-peak Structural Softening” October 1, 1998 M.Sc. in Structural Engineering, Cairo University - September 30, 2000 Topic: ” Flexural Behavior of Tapered Beams” September 1, 1992 B.S. in Civil Engineering, Cairo University, first student over 370- - July 1, 1997 student September 1, 1989 High School, Orman High School, Giza- Egypt - July 1, 1992 September 1, 1986 Junior High School, Orman School, Giza – Egypt - July 1,1989 September 1, 1980 Primary School, Abe Al-Hall School, Giza – Egypt - July 1, 1986 Membership of Professional Societies - Member of the Egyptian Engineering Syndicate 1997 - Member of Japan Concrete Institute 2001 - Design Qualification Certificate of Unlimited Structures from Dubai municipality 2008. Awards - Japanese Governmental Scholarship (Monbusho: Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan). 2000-2003 - Best Project Award, Cairo University, 1997. Work Experience 2015-present CEEE consultation office, Cairo, Egypt. 2008- present Design Manger, EL-DANA Consultation office, UAE. 2008-2010 TSN (The Steel Network - Software and Consultation firm & Egypt and USA) 2004-2008 Design Manger (CEGMAN Consultation Group-Egypt) Prof. Mohamed El- Adwey Nassef ) 2004-present Assistant Professor, Cairo University, Egypt. -

Inventory of Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants of Coastal Mediterranean Cities with More Than 2,000 Inhabitants (2010)

UNEP(DEPI)/MED WG.357/Inf.7 29 March 2011 ENGLISH MEDITERRANEAN ACTION PLAN Meeting of MED POL Focal Points Rhodes (Greece), 25-27 May 2011 INVENTORY OF MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANTS OF COASTAL MEDITERRANEAN CITIES WITH MORE THAN 2,000 INHABITANTS (2010) In cooperation with WHO UNEP/MAP Athens, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .........................................................................................................................1 PART I .........................................................................................................................3 1. ABOUT THE STUDY ..............................................................................................3 1.1 Historical Background of the Study..................................................................3 1.2 Report on the Municipal Wastewater Treatment Plants in the Mediterranean Coastal Cities: Methodology and Procedures .........................4 2. MUNICIPAL WASTEWATER IN THE MEDITERRANEAN ....................................6 2.1 Characteristics of Municipal Wastewater in the Mediterranean.......................6 2.2 Impact of Wastewater Discharges to the Marine Environment........................6 2.3 Municipal Wasteater Treatment.......................................................................9 3. RESULTS ACHIEVED ............................................................................................12 3.1 Brief Summary of Data Collection – Constraints and Assumptions.................12 3.2 General Considerations on the Contents -

País Região Cidade Nome De Hotel Morada Código Postal Algeria

País Região Cidade Nome de Hotel Morada Código Postal Algeria Adrar Timimoun Gourara Hotel Timimoun, Algeria Algeria Algiers Aïn Benian Hotel Hammamet Ain Benian RN Nº 11 Grand Rocher Cap Caxine , 16061, Aïn Benian, Algeria Algeria Algiers Aïn Benian Hôtel Hammamet Alger Route nationale n°11, Grand Rocher, Ain Benian 16061, Algeria 16061 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Safir Alger 2 Rue Assellah Hocine, Alger Centre 16000 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Samir Hotel 74 Rue Didouche Mourad, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Albert Premier 5 Pasteur Ave, Alger Centre 16000 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Suisse 06 rue Lieutenant Salah Boulhart, Rue Mohamed TOUILEB, Alger 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Aurassi Hotel El-Aurassi, 1 Ave du Docteur Frantz Fanon, Alger Centre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre ABC Hotel 18, Rue Abdelkader Remini Ex Dujonchay, Alger Centre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Space Telemly Hotel 01 Alger, Avenue YAHIA FERRADI, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hôtel ST 04, Rue MIKIDECHE MOULOUD ( Ex semar pierre ), 4, Alger Ctre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Dar El Ikram 24 Rue Nezzar Kbaili Aissa, Alger Centre 16000, Algeria 16000 Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Hotel Oran Center 44 Rue Larbi Ben M'hidi, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Es-Safir Hotel Rue Asselah Hocine, Alger Ctre, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre Dar El Ikram 22 Rue Hocine BELADJEL, Algiers, Algeria Algeria Algiers Alger Centre -

Wadi AL-Arish, Sinai, Egypt

American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER 2017 American Journal of Engineering Research (AJER) e-ISSN: 2320-0847 p-ISSN : 2320-0936 Volume-6, Issue-5, pp-172-181 www.ajer.org Research Paper Open Access Developing Flash Floods Inundation Maps Using Remote Sensing Data, a Case Study: Wadi AL-Arish, Sinai, Egypt 1 2 3 Mahmoud S. Farahat , A. M. Elmoustafa , A. A. Hasan 1Demonstrator, Faculty of Engineering, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. 2Associate Professor, Faculty of Engineering, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt, 3Professor of Environmental Hydrology, Faculty of Engineering, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt Abstract: Due to the importance of Sinai as one of the major development axes for the Egyptian government which try to increase/encourage the investment in this region of Egypt, the flood protection arise as a highly important issue due to the damage, danger and other hazards associated to it to human life, properties, and environment. Flash flood, occurred at the last fiveyears in different Egyptian cities, triggered the need of flood risk assessment study for areas highly affected by those floods. Among those areas, AL-Arish city was highly influenced and therefore need a great attention. AL-Arish city has been attacked by many floods at the last five years; these floods triggered the need of the evaluation flood risk, and an early warning system for the areas highly affected by those floods. The study aims to help in establishing a decision support system for the study area by determining the flood extent of wadiAL-Arish, so the damages and losses can be avoided, to reduce flood impact on the developed areas in and around wadi AL-Arish and to improve the flood management in this area in the future.