Instrumentational Complexity of Music Genres and Why Simplicity Sells

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Music-Week-1993-05-0

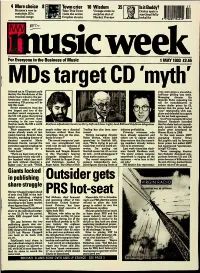

4 Morechoice 8 Town crier 10 Wisdom Kenyon'smaintain vowR3's to Take This Town Vintage comic is musical range visitsCroydon the streets active Marketsurprise Preview star of ■ ^ • H itmsKweek For Everyone in the Business of Music 1 MAY 1993 £2.65 iiistargetCO mftl17 Adestroy forced the eut foundationsin CD prices ofcould the half-hourtives were grillinggiven a lastone-and-a- week. wholeliamentary music selectindustry, committee the par- MalcolmManaging Field, director repeating hisSir toldexaraining this week. CD pricing will be reducecall for dealer manufacturers prices by £2,to twoSenior largest executives and two from of the "cosy"denied relationshipthat his group with had sup- a thesmallest UK will record argue companies that pricing in pliera and defended its support investingchanges willin theprevent new talentthem RichardOur Price Handover managing conceded director thatleader has in mademusic. the UK a world Kaufman adjudicates (centre) as Perry (left) and Ames (right) head EMI and PolyGram délégations atelythat his passed chain hadon thenot immedi-reduced claimsTheir alreadyarguments made will at echolast businesspeople rather without see athose classical fine Tradingmoned. has also been sum- industryPrivately profitability. witnesses who Warnerdealer Musicprice inintroduced 1988. by Goulden,week's hearing. managing Retailer director Alan of recordingsdards for years that ?" set the stan- RobinTemple Morton, managing whose director label othershave alreadyyet to appearedappear admit and managingIn the nextdirector session BrianHMV Discountclassical Centre,specialist warned Music the tionThe was record strengthened companies' posi-last says,spécialisés "We're intrying Scottish to put folk, out teedeep members concem thatalready the commit-believe lowerMcLaughlin prices saidbut addedhe favoured HMV thecommittee music against industry singling for outa independentsweek with the late inclusionHyperion of erwise.music that l'm won't putting be heard oth-out CDsLast to beweek overpriced, committee chair- hadly high" experienced CD sales. -

Electro House 2015 Download Soundcloud

Electro house 2015 download soundcloud CLICK TO DOWNLOAD TZ Comment by Czerniak Maciek. Lala bon. TZ Comment by Czerniak Maciek. Yeaa sa pette. TZ. Users who like Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix ; Users who reposted Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix ; Playlists containing Kemal Coban Electro House Club Mix Electro House by EDM Joy. Part of @edmjoy. Worldwide. 5 Tracks. Followers. Stream Tracks and Playlists from Electro House @ EDM Joy on your desktop or mobile device. An icon used to represent a menu that can be toggled by interacting with this icon. Best EDM Remixes Of Popular Songs - New Electro & House Remix; New Electro & House Best Of EDM Mix; New Electro & House Music Dance Club Party Mix #5; New Dirty Party Electro House Bass Ibiza Dance Mix [ FREE DOWNLOAD -> Click "Buy" ] BASS BOOSTED CAR MUSIC MIX BEST EDM, BOUNCE, ELECTRO HOUSE. FREE tracks! PLEASE follow and i will continue to post songs:) ALL CREDIT GOES TO THE PRODUCERS OF THE SONG, THIS PAGE IS FOR PROMOTIONAL USE ONLY I WILL ONLY POST SONGS THAT ARE PUT UP FOR FREE. 11 Tracks. Followers. Stream Tracks and Playlists from Free Electro House on your desktop or mobile device. Listen to the best DJs and radio presenters in the world for free. Free Download Music & Free Electronic Dance Music Downloads and Free new EDM songs and tracks. Get free Electro, House, Trance, Dubstep, Mixtape downloads. Exclusive download New Electro & House Best of Party Mashup, Bootleg, Remix Dance Mix Click here to download New Electro & House Best of Party Mashup, Bootleg, Remix Dance Mix Maximise Network, Eric Clapman and GANGSTA-HOUSE on Soundcloud Follow +1 entry I've already followed Maximise Music, Repost Media, Maximise Network, Eric. -

Master Thesis the Changes in the Dutch Dance Music Industry Value

Master thesis The changes in the Dutch dance music industry value chain due to the digitalization of the music industry University of Groningen, faculty of Management & Organization Msc in Business Administration: Strategy & Innovation Author: Meike Biesma Student number: 1677756 Supervisor: Iván Orosa Paleo Date: 11 May 2009 Abstract During this research, the Dutch dance music industry was investigated. Because of the changes in the music industry, that are caused by the internet, the Dutch dance music industry has changed accordingly. By means of a qualitative research design, a literature study was done as well as personal interviews were performed in order to investigate what changes occurred in the Dutch dance music industry value chain. Where the Dutch dance music industry used to be a physical oriented industry, the digital music format has replaced the physical product. This has had major implications for actors in the industry, because the digital sales have not compensated the losses that were caused by the decrease in physical sales. The main trigger is music piracy. Digital music is difficult to protect, and it was found that almost 99% of all music available on the internet was illegal. Because of the decline in music sales revenues, actors in the industry have had to change their strategies to remain profitable. New actors have emerged, like digital music retailers and digital music distributors. Also, record companies have changed their business model by vertically integrating other tasks within the dance music industry value chain to be able to stay profitable. It was concluded that the value chain of the Dutch dance music industry has changed drastically because of the digitalization of the industry. -

Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century Saesha Senger University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2020.011 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Senger, Saesha, "Gender, Politics, Market Segmentation, and Taste: Adult Contemporary Radio at the End of the Twentieth Century" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 150. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/150 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Black Metal and Brews

Review: Roadburn Friday 20th April 2018 By Daniel Pietersen Day Two at Roadburn ‘18 and already Never wandering off into too-loose the bar is raised pretty high, with sets jam-band territory, the quartet unleash from Black Decades, Kælan Mikla and some of the best heads-down psych- Servants of the Apocalyptic Goat Rave rock I’ve seen and the crowd absolutely being my personal highlights from the lap it up over the set’s two-hour (two day before. We’ve a lot to get through, hours!) duration. though, and these bands won’t watch themselves. The Ruins of Beverast unleash a black metal stormcloud, all martial drums and lightning-strike guitars sweeping scythe-like over the field of nodding heads in a packed Green Room. It’s a ferocious, scathing display made all the more intense by the devastatingly tight musicianship. An immense start to the Panopticon (Paul Verhagen) day and that’s Roadburn in a nutshell; What Jeremy Bentham, the 18th even the first band on one of the century English philosopher who smaller stages are world class. developed the concept of the Panopticon, would think of his creation’s musical namesake is, sadly, impossible to know. I like to think that, even if the music were beyond him, the passionate social reformer would appreciate the politically relevant sentiments of the band, something which is made most obvious on their opening selection of country- influenced tracks. Banjo and mandolin Motorpsycho (Paul Verhagen) blend with mournful voices, singing of Next door, on the Main Stage, lost families and failing factories, into Motorpsycho are working up their songs that wouldn’t be out of place on groove and creating the kind of sounds, a Steve Earle record. -

Effets & Gestes En Métropole Toulousaine > Mensuel D

INTRAMUROSEffets & gestes en métropole toulousaine > Mensuel d’information culturelle / n°383 / gratuit / septembre 2013 / www.intratoulouse.com 2 THIERRY SUC & RAPAS /BIENVENUE CHEZ MOI présentent CALOGERO STANISLAS KAREN BRUNON ELSA FOURLON PHILLIPE UMINSKI Éditorial > One more time V D’après une histoire originale de Marie Bastide V © D. R. l est des mystères insondables. Des com- pouvons estimer que quelques marques de portements incompréhensibles. Des gratitude peuvent être justifiées… Au lieu Ichoses pour lesquelles, arrivé à un certain de cela, c’est souvent l’ostracisme qui pré- cap de la vie, l’on aimerait trouver — à dé- domine chez certains des acteurs culturels faut de réponses — des raisons. Des atti- du cru qui se reconnaîtront. tudes à vous faire passer comme étranger en votre pays! Il faut le dire tout de même, Cependant ne généralisons pas, ce en deux décennies d’édition et de prosély- serait tomber dans la victimisation et je laisse tisme culturel, il y a de côté-ci de la Ga- cet art aux politiques de tous poils, plus ha- ronne des décideurs/acteurs qui nous biles que moi dans cet exercice. D’autant toisent quand ils ne nous méprisent pas tout plus que d’autres dans le métier, des atta- simplement : des organisateurs, des musi- ché(e)s de presse des responsables de ciens, des responsables culturels, des théâ- com’… ont bien compris l’utilité et la néces- treux, des associatifs… tout un beau monde sité d’un média tel que le nôtre, justement ni qui n’accorde aucune reconnaissance à inféodé ni soumis, ce qui lui permet une li- photo © Lisa Roze notre entreprise (au demeurant indépen- berté d’écriture et de publicité (dans le réel dante et non subventionnée). -

Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews На Arrhythmia Sound

2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound Home Content Contacts About Subscribe Gallery Donate Search Interviews Reviews News Podcasts Reports Home » Reviews Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) Submitted by: Quarck | 19.04.2008 no comment | 198 views Aaron Spectre , also known for the project Drumcorps , reveals before us completely new side of his work. In protovoves frenzy breakgrindcore Specter produces a chic downtempo, idm album. Lost Tracks the result of six years of work, but despite this, the rumor is very fresh and original. The sound is minimalistic without excesses, but at the same time the melodies are very beautiful, the bit powerful and clear, pronounced. Just want to highlight the composition of Break Ya Neck (Remix) , a bit mystical and mysterious, a feeling, like wandering somewhere in the http://www.arrhythmiasound.com/en/review/aaron-spectre-lost-tracks-ad-noiseam-2007.html 1/3 2/22/2018 Aaron Spectre «Lost Tracks» (Ad Noiseam, 2007) | Reviews на Arrhythmia Sound dusk. There was a place and a vocal, in a track Degrees the gentle voice Kazumi (Pink Lilies) sounds. As a result, Lost Tracks can be safely put on a par with the works of such mastadonts as Lusine, Murcof, Hecq. Tags: downtempo, idm Subscribe Email TOP-2013 Submit TOP-2014 TOP-2015 Tags abstract acid ambient ambient-techno artcore best2012 best2013 best2014 best2015 best2016 best2017 breakcore breaks cyberpunk dark ambient downtempo dreampop drone drum&bass dub dubstep dubtechno electro electronic experimental female vocal future garage glitch hip hop idm indie indietronica industrial jazzy krautrock live modern classical noir oldschool post-rock shoegaze space techno tribal trip hop Latest The best in 2017 - albums, places 1-33 12/30/2017 The best in 2017 - albums, places 66-34 12/28/2017 The best in 2017. -

Design Project: Big Beat DJ Project Overview

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute Department of Electrical, Computer, and Systems Engineering ECSE 4560: Signal Processing Design, Spring 2003 Professor: Richard Radke, JEC 7006, 276-6483 Design Project: Big Beat DJ “I never worked a day in my life; I just laid back and let the big beat lead me.” - The Jungle Brothers Project Overview A good techno DJ spins a continuous stream of music by seamlessly mixing one song into the next. This involves not only synchronizing the beats of the songs to be mixed, but also incrementally adjusting the pitches of the songs so that during the transition, neither song sounds unnatural. Your goal in this project is to use signal processing to produce a computerized DJ that can automatically produce a non-stop mix of music given a library of non-synchronized tracks as input. On top of this basic specification, additional points will be given for implementing advanced techniques like sampling, beat juggling and airbeats that make the mix more exciting. At the end of the term, the computer DJs will face off in a Battle for World Supremacy with a library of entirely novel songs. Basic Deliverables To meet the basic design requirement, your group should deliver • An m-file named bpm.m with syntax b = bpm(song) where song is the name of a music .wav file (or the vector of music samples themselves), and b is the estimated number of beats per minute in the specified song. • An m-file named songmix.m with syntax mix = = songmix(song1,song2), where mix is the resultant continuous mix between song1 and song2. -

A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us

Pace University DigitalCommons@Pace Pace Law Faculty Publications School of Law 2011 No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson Jr. Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Horace E. Anderson, Jr., No Bitin’ Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us, 20 Tex. Intell. Prop. L.J. 115 (2011), http://digitalcommons.pace.edu/lawfaculty/818/. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. No Bitin' Allowed: A Hip-Hop Copying Paradigm for All of Us Horace E. Anderson, Jr: I. History and Purpose of Copyright Act's Regulation of Copying ..................................................................................... 119 II. Impact of Technology ................................................................... 126 A. The Act of Copying and Attitudes Toward Copying ........... 126 B. Suggestions from the Literature for Bridging the Gap ......... 127 III. Potential Influence of Norms-Based Approaches to Regulation of Copying ................................................................. 129 IV. The Hip-Hop Imitation Paradigm ............................................... -

Outsiders' Music: Progressive Country, Reggae

CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s Chapter Outline I. The Outlaws: Progressive Country Music A. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, mainstream country music was dominated by: 1. the slick Nashville sound, 2. hardcore country (Merle Haggard), and 3. blends of country and pop promoted on AM radio. B. A new generation of country artists was embracing music and attitudes that grew out of the 1960s counterculture; this movement was called progressive country. 1. Inspired by honky-tonk and rockabilly mix of Bakersfield country music, singer-songwriters (Bob Dylan), and country rock (Gram Parsons) 2. Progressive country performers wrote songs that were more intellectual and liberal in outlook than their contemporaries’ songs. 3. Artists were more concerned with testing the limits of the country music tradition than with scoring hits. 4. The movement’s key artists included CHAPTER TWELVE: OUTSIDERS’ MUSIC: PROGRESSIVE COUNTRY, REGGAE, SALSA, PUNK, FUNK, AND RAP, 1970s a) Willie Nelson, b) Kris Kristopherson, c) Tom T. Hall, and d) Townes Van Zandt. 5. These artists were not polished singers by conventional standards, but they wrote distinctive, individualist songs and had compelling voices. 6. They developed a cult following, and progressive country began to inch its way into the mainstream (usually in the form of cover versions). a) “Harper Valley PTA” (1) Original by Tom T. Hall (2) Cover version by Jeannie C. Riley; Number One pop and country (1968) b) “Help Me Make It through the Night” (1) Original by Kris Kristofferson (2) Cover version by Sammi Smith (1971) C. -

Networks of Music Groups As Success Predictors

Networks of Music Groups as Success Predictors Dmitry Zinoviev Mathematics and Computer Science Department Suffolk University Boston, Massachussets 02114 Email: dzinoviev@suffolk.edu Abstract—More than 4,600 non-academic music groups process of penetration of the Western popular music culture emerged in the USSR and post-Soviet independent nations in into the post-Soviet realm but fails to outline the aboriginal 1960–2015, performing in 275 genres. Some of the groups became music landscape. On the other hand, Bright [12] presents an legends and survived for decades, while others vanished and are known now only to select music history scholars. We built a excellent narrative overview of the non-academic music in the network of the groups based on sharing at least one performer. USSR from the early XXth century to the dusk of the Soviet We discovered that major network measures serve as reason- Union—but with no quantitative analysis. Sparse and narrowly ably accurate predictors of the groups’ success. The proposed scoped studies of few performers [13] or aspects [14] only network-based success exploration and prediction methods are make the barren landscape look more barren. transferable to other areas of arts and humanities that have medium- or long-term team-based collaborations. In this paper, we apply modern quantitative analysis meth- Index Terms—Popular music, network analysis, success pre- ods, including statistical analysis, social network analysis, and diction. machine learning, to a collection of 4,600 music groups and bands. We build a network of groups, quantify groups’ success, I. Introduction correlate it with network measures, and attempt to predict Exploring and predicting the success of creative collabo- success, based solely on the network measures. -

High Concept Music for Low Concept Minds

High concept music for low concept minds Music | Bittles’ Magazine: The music column from the end of the world: August/September New albums reviewed Part 1 Music doesn’t challenge anymore! It doesn’t ask questions, or stimulate. Institutions like the X-Factor, Spotify, EDM and landfill pop chameleons are dominating an important area of culture by churning out identikit pop clones with nothing of substance to say. Opinion is not only frowned upon, it is taboo! By JOHN BITTLES This is why we need musicians like The Black Dog, people who make angry, bitter compositions, highlighting inequality and how fucked we really are. Their new album Neither/Neither is a sonically dense and thrilling listen, capturing the brutal erosion of individuality in an increasingly technological and state-controlled world. In doing so they have somehow created one of the most mesmerising and important albums of the year. Music isn’t just about challenging the system though. Great music comes in a wide variety of formats. Something proven all too well in the rest of the albums reviewed this month. For instance, we also have the experimental pop of Georgia, the hazy chill-out of Nils Frahm, the Vangelis-style urban futurism of Auscultation, the dense electronica of Mueller Roedelius, the deep house grooves of Seb Wildblood and lots, lots more. Somehow though, it seems only fitting to start with the chilling reflection on the modern day systems of state control that is the latest work by UK electronic veterans The Black Dog. Their new album has, seemingly, been created in an attempt to give the dispossessed and repressed the knowledge of who and what the enemy is so they may arm themselves and fight back.