A Linguistic Bridge Between Alienation and Intimacy: Chabad's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Shul Weekly Magazine Sponsored by Mr

B”H The Shul weekly magazine Sponsored By Mr. & Mrs. Martin (OBM) and Ethel Sirotkin and Dr. & Mrs. Shmuel and Evelyn Katz Shabbos Parshas Vaeira Shabbos Mevarchim Teves 27 - 28 January 4 - 5 CANDLE LIGHTING: 5:25 pm Shabbos Ends: 6:21 pm Rosh Chodesh Shevat Monday January 7 Molad - New Moon Sunday, January 6 11:13 (14 chalakim) AM Te Shul - Chabad Lubavitch - An institution of Te Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem M. Schneerson (May his merit shield us) Over Tirty fve Years of Serving the Communities of Bal Harbour, Bay Harbor Islands, Indian Creek and Surfside 9540 Collins Avenue, Surfside, Fl 33154 Tel: 305.868.1411 Fax: 305.861.2426 www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] www.theshulpreschool.org www.cyscollege.org The Shul Weekly Magazine Everything you need for every day of the week Contents Nachas At A Glance Weekly Message 3 Our Teen girls go out onto the streets of 33154 before Thoughts on the Parsha from Rabbi Sholom D. Lipskar Shabbos to hand out shabbos candles and encourage all A Time to Pray 5 Jewish women and girls to light. Check out all the davening schedules and locations throughout the week Celebrating Shabbos 6-7 Schedules, classes, articles and more... Everything you need for an “Over the Top” Shabbos experience Community Happenings 8 - 9 Sharing with your Shul Family 10-15 Inspiration, Insights & Ideas Bringing Torah lessons to LIFE 16- 19 Get The Picture The full scoop on all the great events around town 20 French Connection Refexions sur la Paracha Latin Link 21 Refexion Semanal 22 In a woman’s world Issues of relevance to the Jewish woman The Hebrew School children who are participating in a 23-24 countrywide Jewish General Knowledge competition, take Networking Effective Advertising the 2nd of 3 tests. -

Sichos of 5705

Selections from Sefer HaSichos 5701-5705 Talks Delivered by RABBI YOSEF YITZCHAK SCHNEERSOHN OF LUBAVITCH Rosh HaShanah Selections from Sefer HaSichos 5701-5705 TALKS DELIVERED IN 5701-5705 (1941-1945) BY RABBI YOSEF YITZCHAK SCHNEERSOHN זצוקללה"ה נבג"מ זי"ע THE SIXTH LUBAVITCHER REBBE Translated and Annotated by Uri Kaploun ROSH HASHANAH Kehot Publication Society 770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11213 5781 • 2020 edication D This Sefer is Dedicated in Honor of שיחיו Shmuel and Rosalynn Malamud by their childrenS and grandchildren, the Malamud Family, Crown Heights, NY Moshe and SElke Malamud Yisrael, Leba, Hadas and Rachel Alexandra Yossi and KayliS Malamud Yisroel, Shloime, Yechezkel, Menachem Mendel, Laivi Yitzchok and Eliyahu Chesky and ChanaS Malamud Hadas, Shaina Batya and Rachel David Eliezer HaLevi andS Sarah Rachel Popack Dov HaLevi, Nena Nechama, Hadas and Shlomo HaLevi A Prayer and a Wish The following unconnected selections are gleaned from Rosh HaShanah farbrengens of the Rebbe Rayatz, as translated in the eight-volume Sefer HaSichos series that includes: Sefer HaSichos 5701, Sefer HaSichos 5702, Sefer HaSichos 5704, and Sefer HaSichos 5705. After quoting a brief maamar of the Alter Rebbe, the Rebbe Rayatz concludes: “Elder chassidim used to relate that by delivering that maamar, the Alter Rebbe uncovered in his chassidim the light of the soul. Within all of them, even within the most ordinary chassidim, their souls stood revealed.” The prayer and the wish that we share with our readers is that in us, too, pondering over these selections will enable the soul within us, too, to stand revealed. 3 29 Elul, 5700 (1940):1 Erev Rosh HaShanah, 5701 (1940) 1. -

Farbrengen Wi Th the Rebbe

פארברענגען התוועדות י״ט כסלו ה׳תשמ״ב עם הרבי Farbrengen wi th the Rebbe english úמי בúימ עו וﬢ ‰ﬧ ו ﬨו ﬨ ר ע ﬨ ˆ ר ﬡ ﬡ י מ נ ו פארברענגען עם הרבי פארברענגען עם הרבי י״ט כסלו תשמ״ב Published and Copyrighted by © VAAD TALMIDEI HATMIMIM HAOLAMI 770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213 Tel: 718 771 9674 Email: [email protected] VAADHATMIMIM.ORG The Sichos included in this Kovetz are printed with permission of: “Jewish Educational Media” We thank them greatly for this. INDEX Maamar 5 Maamar Padah Beshalom Sicha 1 11 Not the Same Old Story Sicha 2 17 A Voice with No Echo Sicha 3 23 Learning Never Ends Sicha 4 31 Called to Duty Sicha 5 35 Write for yourselves this Song…; Hadran on Minyan Hamitzvos; in honor of the Mivtzah of Ois B’sefer Torah Sicha 6 51 Architects of Peace; Hadran on Maseches Brachos Sicha 7 71 Full time occupation Sicha 8 73 The Road to Peace Sicha 9 87 In Word and in Deed Maamar Maamar Padah Beshalom Peace in our Avodas Hashem Padah Beshalom – peace in our Avodas Hashem. התוועדות י״ט כסלו ה׳תשמ״ב 6 MAAMAR 1. “He delivered my soul in peace from battles against me, because of the many who were with me.” The Alter Rebbe writes in his letter that this verse relates to his liberation, for while reciting this verse, before reciting the following verse, he was notified that he was free. Consequently, many maamarim said on Yud Tes Kislev begin with, and are based on this verse. -

Chapter 51 the Tanya of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, Elucidated by Rabbi Yosef Wineberg Published and Copyrighted by Kehot Publication Society

Chapter 51 The Tanya of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, elucidated by Rabbi Yosef Wineberg Published and copyrighted by Kehot Publication Society « Previous Next » Chapter 50 Chapter 52 The title-page of Tanya tells us that the entire work is based upon the verse (Devarim 30:14), “For this thing (the Torah) is very near to you, in your mouth and in your heart, that you may do it.” And the concluding phrase (“that you may do it”) implies that the ultimate purpose of the entire Torah is the fulfillment of the mitzvot in practice. In order to clarify this, ch. 35 began to explain the purpose of the entire Seder Hishtalshelut (“chain of descent” of spiritual levels from the highest emanation of the Creator down to our physical world), and of man’s serving G‑d. The purpose of both is to bring a revelation of G‑d’s Presence into this lowly world, and to elevate the world spiritually so that it may become a fitting dwelling-place for His Presence. To further explain this, ch. 35 quoted the words of the Yenuka in the Zohar that a Jew should not walk four cubits bareheaded because the Shechinah dwells above his head. This light of the Divine Presence, continues the Zohar, resembles the light of a lamp, where oil and wick are needed for the flame to keep burning. A Jew should therefore be aware, says the Zohar, of the Shechinah above him and keep it supplied with “oil” (good deeds), in order to ensure that the “flame” of the Shechinah keeps its hold on the “wick” (the physical body). -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

747 B Beis Moshiach 28/06/2010 8:34 AM Page 3

747_B_Beis Moshiach 28/06/2010 8:34 AM Page 3 contents TOUCHING THE CORE 4 D’var Malchus | Sichos In English MOSHIACH: IT’S GOTTA BE PERSONAL 6 Thought | Rabbi Zvi Homnick MESHUGE, MESHUGE BUT YOU’VE GOT 10 TO HAVE SECHEL! Moshiach & Geula | Rabbi Chaim Ahkenazi a”h ‘DUBRAWSKI CAN BE RELIED UPON’ 14 Obituary | Avrohom Rainitz WAS THAT AN EARTHQUAKE 24 USA OR A TRAIN? 744 Eastern Parkway Moshiach & Science | Dr. Aryeh Gotfryd, PhD Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409 Tel: (718) 778-8000 Fax: (718) 778-0800 I FEEL THE REBBE’S HANDS [email protected] 28 Feature | Nosson Avrohom www.beismoshiach.org EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: M.M. Hendel ENGLISH EDITOR: RISHON L’TZIYON: RABBI MORDECHAI Boruch Merkur HEBREW EDITOR: 36 ELIYAHU ZT”L Rabbi Sholom Yaakov Chazan Feature | Shneur Zalman Levin [email protected] Beis Moshiach (USPS 012-542) ISSN 1082- 0272 is published weekly, except Jewish holidays (only once in April and October) for $160.00 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn and in all other places for $180.00 per year (45 issues), by Beis Moshiach, 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Periodicals postage paid at Brooklyn, NY and additional offices. Postmaster: send address changes to Beis Moshiach 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Copyright 2010 by Beis Moshiach, Inc. Beis Moshiach is not responsible for the content of the advertisements. 747_B_Beis Moshiach 28/06/2010 8:34 AM Page 4 d’var malchus Our Sages relate [5] that when a Jewish man is cohabitating with a non-Jewish woman, “the zealous TOUCHING have [the right [6] to] strike him.” Nevertheless, “although this is the law, a ruling is not delivered.” If a person were to ask a Jewish court if he should kill a person THE CORE who commits such an act, the court should not instruct him to do so. -

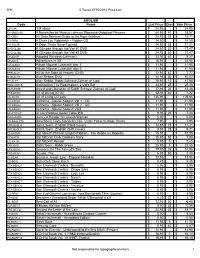

B"H 5 Teves 5775/2014 Price List ENGLISH Code Name List Price

B"H 5 Teves 5775/2014 Price List ENGLISH Code Name List Price Disc Sale Price EO-334I 334 Ideas $ 24.95 $ 24.95 EY-5NOV.SB 5 Novelettes by Marcus Lehman Slipcased (Adopted Princess, $ 64.95 40 $ 38.97 EF-60DA 60 Days Spiritual Guide to the High Holidays $ 24.95 25 $ 18.71 CD-DIRA A Dirah Loy Yisboraich - Yiddish CD $ 14.50 $ 14.50 EO-DOOR A Door That's Never Locked $ 14.95 25 $ 11.21 DVD-GLIM1 A Glimpse through the Veil #1 DVD $ 24.95 30 $ 17.47 DVD-GLIM2 A Glimpse through the Veil #2 DVD $ 24.95 30 $ 17.47 EY-ADOP Adopted Princess (Lehman) $ 13.95 40 $ 8.37 EY-ADVE Adventures in 3D $ 16.95 $ 16.95 CD-ALBU1 Album Nigunei Lubavitch disc 1 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ALBU2 Album Nigunei Lubavitch disc 2 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 ERR-ALLF All for the Sake of Heaven (CHS) $ 12.95 40 $ 7.77 DVD-ALTE Alter Rebbe, DVD $ 14.95 30 $ 10.47 EY-ALTE Alter Rebbe: Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi $ 19.95 10 $ 17.96 EMO-ANTI.S Anticipating The Redemption, 2 Vol's Set $ 33.95 25 $ 25.46 EAR-ARRE Arrest and Liberation of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi $ 17.95 25 $ 13.46 ETZ-ARTO Art of Giving (CHS) $ 12.95 40 $ 7.77 CD-ARTO Art of Living CD sets $ 125.95 $ 125.95 CD-ASHR1 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol 1 - CD $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ASHR2 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol 2 - CD $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ASHR3 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol3 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 EP-ATOU.P At Our Rebbes' Seder Table P/B $ 9.95 25 $ 7.46 EWO-AURA Aura - A Reader On Jewish Woman $ 5.00 $ 5.00 CD-BAALSTS Baal Shem Tov's Storyteller CD - Uncle Yossi Heritage Series $ 7.95 $ 7.95 EFR-BASI.H Basi L'Gani - English (Hard Cover) -

Chabad Chodesh Nisan 5774

בס“ד Nisan 5774/2014 SPECIAL DAYS IN NISAN Volume 25, Issue 1 Nisan 1/April 1/ Tuesday Rosh Chodesh Nisan In Nisan the Avos were born and died. [Rosh HaShanah, 11a] In Nisan our fathers were redeemed and in Nisan we will be redeemed. [Rosh HaShanah, 11a] The dedication of the Mishkan began on Nisan 1, 2449 (1312 BCE) and Moshe Rabeinu completed the consecration of Aharon and his sons. Aharon brought the first sacrifices. The Nesiim, heads of the tribes, brought sacrifices from the first until the twelfth of Nisan, to dedicate the Mishkan. "...We don't fast in Nisan, nor decree a fast on the community, a custom based on the words of the Chachamim [Maseches Soferim]: The Nesiim began to bring their sacrifices in Nisan, through the twelfth. Each day was the Nasi's own Yom Tov. The fourteenth is Erev Chizkiyahu HaMelech began recon-struction Pesach, followed by eight days of Pesach; since of the first Beis HaMikdash, 3199 (562 BCE). most of the month went by in holiness, we [Divrei HaYamim II, 29-17] make it all holy as a Yom Tov..." [Alter Rebbe's Shulchan Aruch, 429:9] (And thus, we don't During the dedication of the Second Beis say Tachnun, "Av HaRachamim" or HaMikdash, [Ezra 6:15-18] "...They brought "Tzidkascha" in Nisan) sacrifices just as they did in the days of Moshe Rabeinu" [Menachos 45a], 3413 (348 From Rosh Chodesh Nisan until Nisan 12, we BCE). say the daily Parshah of the sacrifice of each Nasi, after Shacharis, followed by "Yehi On Rosh Chodesh Nisan the dedication of the Ratzon". -

Moshiach Weekly Chof Zayin Adar 5774 a WORD from the EDITORS - Ad Mosai?!

$2.00 . וההוספה בלימוד התורה בעניני משיח והגאולה היא ה"דרך שער הישרה" לפעול התגלות וביאת משיח והגאולה בפועל ממש )משיחת ש"פ תזו"מ ה'תנש"א( The Chossid Who Propagated Moshiach Reb Michoel Teitelbaum I Don't Let My דער רבי זאל זיין געזונט און שטארק! Chassidim Sleep The Story of a Most The World Is Waiting Unforgettable Winter יחי אדוננו מורנו ורבינו מלך המשיח לעולם ועד Index Chof Zayin Adar 5774 - Ad Mosai?! 3 A word from the Editors The Story of a Most Unforgettable Winter דער רבי זאל זיין געזונט און שטארק! 4 Ahavas Yisroel and Moshiach 13 Ksav Yad Kodesh 4 11 I Don't Let My Chassidim Sleep 14 The world is waiting Will they ever come?! 21 A Story רצוננו לראות את מלכנו 24 Ad Mosai Sunday he searches, Monday he searches זונטיג געזוכט, ָמאנטיג געזוכט 26 26 The Chossid Who Propagated Moshiach 32 Reb Michoel Teitelbaum ENOUGH IS ENOUGH! 38 Daloy Golus 24 32 2 | Moshiach Weekly Chof Zayin Adar 5774 A WORD FROM THE EDITORS - Ad Mosai?! It is with great pleasure that we pres- to live with their message and bring ent our readership with this Expanded them down into our daily lives. Edition of Moshiach Weekly, which is In the days leading up to Chof Zayin being released in time for 27 Adar, the Adar, the Rebbe stressed the fact that day when the great helem v'hester be- it's an 'iber yohr' and that there are two gan. months of Adar totaling a 60 day pe- As we approach this moment, and riod of Simcha. -

Chabad Chodesh Elul 5780

בס“ד Elul 5780/2020 SPECIAL DAYS IN ELUL Volume 31, Issue 6 Menachem Av 30/August 20/Thursday First Day Rosh Chodesh Elul We begin to say "L’Dovid HaShem Ori" at Shacharis and Minchah. Plague of Lice in Mitzrayim. Moshe Rabeinu went up to Har Sinai to receive the second Luchos. (Shemos 33:11, Rashi) Wedding of R. Boruch, son of the Mitteler Rebbe and Rebbitzen Beila Reiza, daughter of R. Chayim Avraham, son of the Alter Rebbe, 5582 [1822]. Elul 1/August 21/Friday Second Day Rosh Chodesh Elul We begin to say three extra chapters of Tehillim, completing Sefer Tehillim by Yom Kippur, a custom received from the Baal R. Yisroel of Polotzk, reached Eretz Yisrael, Shem Tov. 5537 [1777]. We begin to blow the Shofar every day Elul 7/August 27/Thursday (except Shabbos) after Shacharis. Amram remarried Yocheved (Moshe "In Elul we blow ten blasts daily, except Rabeinu was born seven months later), on Shabbos, paralleling the ten powers of the 2367 [1394 BCE] (Sotah 12a) Nefesh; on Rosh HaShanah we blow one hundred to awaken the ten powers, and the Yartzeit of the Meraglim who spoke against ten powers that each of THEM Eretz Yisrael, 2448 [1313 BCE], (Sotah 35a, contain..." [Likutei Sichos Vol. II, p. 446] Beis Yosef to Tur Orach Chaim 580) In the days of the later Amoraim, beginning Agrippa I dedicated the new gate of the TZCHOK CHABAD OF HANCOCKof PARK Chodesh Kalah, month of study (". ..and a wall of Yerushalayim, [42], once a holiday. pillar of fire came down for them from (Megilas Taanis 6) heaven") [Tosafos, Brachos 17a]. -

764 Beis Moshiach 15/11/2010 9:34 AM Page 3

764_Beis Moshiach 15/11/2010 9:34 AM Page 3 contents WE SEE G-D’S HAND IN THE HOLY 4 LAND [CONT.] D’var Malchus CHASSIDIC UNITY TO BRING 7 MOSHIACH Thought | Rabbi Zvi Homnick THE SHLICHUS OF GABI AND RIVKY 10 CONTINUES! Feature | Rabbi Sholom Yaakov Chazan HOLY DOUGHNUTS 14 Moshiach & Science | Aryeh Gotfryd, PhD WHEN A REBBE MARRIES 14 Kislev 16 USA 744 Eastern Parkway Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409 Tel: (718) 778-8000 RED ALERT! NETANYAHU STARTS Fax: (718) 778-0800 20 [email protected] GOLAN WITHDRAWAL www.beismoshiach.org Shleimus HaAretz | Raanan Isserof EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: GEULA: WHAT ARE WE WAITING FOR? M.M. Hendel 24 Moshiach & Geula | R’ Gershon Avtzon ENGLISH EDITOR: Boruch Merkur [email protected] HEBREW EDITOR: SAYING “NO” TO LAVISH WEDDINGS Rabbi Sholom Yaakov Chazan 26 Feature | Yisroel Yehuda [email protected] Beis Moshiach (USPS 012-542) ISSN 1082- FROM PRAGUE TO BELGIUM 0272 is published weekly, except Jewish Memoirs | Rabbi Schneur Zalman Chanin holidays (only once in April and October) for 34 $160.00 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn and in all other places for $180.00 per year (45 issues), by Beis Moshiach, 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. STORIES FROM THE KINUS Periodicals postage paid at Brooklyn, NY and 38 additional offices. Postmaster: send address HA’SHLUCHIM changes to Beis Moshiach 744 Eastern Stories Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Copyright 2010 by Beis Moshiach, Inc. ANOTHER FORM OF DIPLOMACY Beis Moshiach is not responsible for the 42 Shleimus HaAretz | Sholom Ber Crombie content of the advertisements. -

Weekly Bulletin Single Pages.Qxd

s’’xc Shabbat Bo Chabad of the West Side & Chabad Early Learning Center Shevat 7-8, 5767 January 26-27, 2007 Candle Lighting: 4:47 PM Shabbat Ends: 5:50 PM Weekly Bulletin V OLUME IFRIDAY, JANUARY 26, 2007 7 SHEVAT, 5767 ISSUE XXII Chabad Around the World Celebrates 10 Shevat The tenth day of the loved one loves. Hebrew month of Shevat marks the day of Rabbi Schneur Zalman was the founder of the the passing of the Chabad branch of Chassidism, and his teachings on Previous Lubavitcher the love of G-d and man form an integral part of the Rebbe, Rabbi Yosef philosophy and ethos of Chabad. Following Rabbi Yitzchok Schneerson in Schneur Zalman's passing in 1812, his son and suc- 1950 and the assuming cessor, Rabbi DovBer, settled in the town of of the leadership of Lubavitch which served as the movement's head- Chabad by his son-in-law and successor, the quarters for the next 102 years. Was it by coinci- Rebbe. dence or design that Rabbi DovBer chose Love According to the Rebbe a place whose name Sunday, By Yanki Tauber means "Town of Love"? Lubavitchers January 28 What if someone said to you, "I love you, but I don't (as Chabad like your children?" You'd probably say: "You may Chassidim are also think that you love me, but you don't really. You don't known) will simply Farbrengen care for what I care most deeply about. Obviously, answer that there's you don't know anything about me, and you don't no such thing as Celebrating know what love is, either!" "coincidence", for Yud Shevat even the seemingly The Torah commands us to "Love your fellow as minor events of our Join us for an inspira- yourself." The Torah also tells us to "Love the L-rd lives are guided by tional farbrengen (chas- your G-d." This prompted the disciples of Rabbi divine providence sidic get-together) as we Schneur Zalman of Liadi (1745-1812) to ask their and are replete with master: "Which is the greater virtue, love of G-d or significance.