I Am the Lubavitcher Rebbe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Does a Yartzheit 21 Years Ago Feel Like

From: "Rabbi Areyah Kaltmann" <[email protected]> Subject: How does a yartzheit 21 years ago feel like yesterday? Date: June 19, 2015 10:55:32 AM EDT To: "[email protected]" <[email protected]> Reply-To: <[email protected]> Dear Ellie Candle Lighting Times for There are many methods of educating, or passing on a message. Some teachers preach, others speak inspiring New Albany, OH [Based on Zip Code words, and then you have the creative people who use hands-on methods. All these are excellent for 43054]: transmitting information. But when it comes to teaching morality, teaching a way of life, none of these Shabbat Candle Lighting: methods are strong enough. The Rebbe changed many lives, but not by preaching and not by lecturing. He Friday, Jun 19 8:45 pm Shabbat Ends: was simply a living example. His love for each and every Jew and human being, and his self-sacrifice for the Shabbat, Jun 20 9:53 pm ideals of Judaism inspired a whole generation. Torah Portion: Korach This Shabbat marks the 21st Yahrzeit (anniversary of passing) of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson of righteous memory. The day of passing of a holy tzadik is an auspicious day to reflect and bond with the tzadik's soul and to ask the tzadik to intercede on High on our behalf. Therefore, the day of the Rebbe's passing, is an opportune time to pray at the Ohel, the Rebbe's resting place in Queens. Schedule of Services I am I will G-d willing, be at the Ohel this Shabbos together with some tens of thousands of other people from The Lori Schottenstein Chabad Center offers a around the world and I would like to pray for you as well at the Rebbe's "Ohel." If you send me your name and full schedule of Shabbat services. -

The Shul Weekly Magazine Sponsored by Mr

B”H The Shul weekly magazine Sponsored By Mr. & Mrs. Martin (OBM) and Ethel Sirotkin and Dr. & Mrs. Shmuel and Evelyn Katz Shabbos Parshas Vaeira Shabbos Mevarchim Teves 27 - 28 January 4 - 5 CANDLE LIGHTING: 5:25 pm Shabbos Ends: 6:21 pm Rosh Chodesh Shevat Monday January 7 Molad - New Moon Sunday, January 6 11:13 (14 chalakim) AM Te Shul - Chabad Lubavitch - An institution of Te Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem M. Schneerson (May his merit shield us) Over Tirty fve Years of Serving the Communities of Bal Harbour, Bay Harbor Islands, Indian Creek and Surfside 9540 Collins Avenue, Surfside, Fl 33154 Tel: 305.868.1411 Fax: 305.861.2426 www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] www.theshulpreschool.org www.cyscollege.org The Shul Weekly Magazine Everything you need for every day of the week Contents Nachas At A Glance Weekly Message 3 Our Teen girls go out onto the streets of 33154 before Thoughts on the Parsha from Rabbi Sholom D. Lipskar Shabbos to hand out shabbos candles and encourage all A Time to Pray 5 Jewish women and girls to light. Check out all the davening schedules and locations throughout the week Celebrating Shabbos 6-7 Schedules, classes, articles and more... Everything you need for an “Over the Top” Shabbos experience Community Happenings 8 - 9 Sharing with your Shul Family 10-15 Inspiration, Insights & Ideas Bringing Torah lessons to LIFE 16- 19 Get The Picture The full scoop on all the great events around town 20 French Connection Refexions sur la Paracha Latin Link 21 Refexion Semanal 22 In a woman’s world Issues of relevance to the Jewish woman The Hebrew School children who are participating in a 23-24 countrywide Jewish General Knowledge competition, take Networking Effective Advertising the 2nd of 3 tests. -

Sichos of 5705

Selections from Sefer HaSichos 5701-5705 Talks Delivered by RABBI YOSEF YITZCHAK SCHNEERSOHN OF LUBAVITCH Rosh HaShanah Selections from Sefer HaSichos 5701-5705 TALKS DELIVERED IN 5701-5705 (1941-1945) BY RABBI YOSEF YITZCHAK SCHNEERSOHN זצוקללה"ה נבג"מ זי"ע THE SIXTH LUBAVITCHER REBBE Translated and Annotated by Uri Kaploun ROSH HASHANAH Kehot Publication Society 770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11213 5781 • 2020 edication D This Sefer is Dedicated in Honor of שיחיו Shmuel and Rosalynn Malamud by their childrenS and grandchildren, the Malamud Family, Crown Heights, NY Moshe and SElke Malamud Yisrael, Leba, Hadas and Rachel Alexandra Yossi and KayliS Malamud Yisroel, Shloime, Yechezkel, Menachem Mendel, Laivi Yitzchok and Eliyahu Chesky and ChanaS Malamud Hadas, Shaina Batya and Rachel David Eliezer HaLevi andS Sarah Rachel Popack Dov HaLevi, Nena Nechama, Hadas and Shlomo HaLevi A Prayer and a Wish The following unconnected selections are gleaned from Rosh HaShanah farbrengens of the Rebbe Rayatz, as translated in the eight-volume Sefer HaSichos series that includes: Sefer HaSichos 5701, Sefer HaSichos 5702, Sefer HaSichos 5704, and Sefer HaSichos 5705. After quoting a brief maamar of the Alter Rebbe, the Rebbe Rayatz concludes: “Elder chassidim used to relate that by delivering that maamar, the Alter Rebbe uncovered in his chassidim the light of the soul. Within all of them, even within the most ordinary chassidim, their souls stood revealed.” The prayer and the wish that we share with our readers is that in us, too, pondering over these selections will enable the soul within us, too, to stand revealed. 3 29 Elul, 5700 (1940):1 Erev Rosh HaShanah, 5701 (1940) 1. -

Farbrengen Wi Th the Rebbe

פארברענגען התוועדות י״ט כסלו ה׳תשמ״ב עם הרבי Farbrengen wi th the Rebbe english úמי בúימ עו וﬢ ‰ﬧ ו ﬨו ﬨ ר ע ﬨ ˆ ר ﬡ ﬡ י מ נ ו פארברענגען עם הרבי פארברענגען עם הרבי י״ט כסלו תשמ״ב Published and Copyrighted by © VAAD TALMIDEI HATMIMIM HAOLAMI 770 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213 Tel: 718 771 9674 Email: [email protected] VAADHATMIMIM.ORG The Sichos included in this Kovetz are printed with permission of: “Jewish Educational Media” We thank them greatly for this. INDEX Maamar 5 Maamar Padah Beshalom Sicha 1 11 Not the Same Old Story Sicha 2 17 A Voice with No Echo Sicha 3 23 Learning Never Ends Sicha 4 31 Called to Duty Sicha 5 35 Write for yourselves this Song…; Hadran on Minyan Hamitzvos; in honor of the Mivtzah of Ois B’sefer Torah Sicha 6 51 Architects of Peace; Hadran on Maseches Brachos Sicha 7 71 Full time occupation Sicha 8 73 The Road to Peace Sicha 9 87 In Word and in Deed Maamar Maamar Padah Beshalom Peace in our Avodas Hashem Padah Beshalom – peace in our Avodas Hashem. התוועדות י״ט כסלו ה׳תשמ״ב 6 MAAMAR 1. “He delivered my soul in peace from battles against me, because of the many who were with me.” The Alter Rebbe writes in his letter that this verse relates to his liberation, for while reciting this verse, before reciting the following verse, he was notified that he was free. Consequently, many maamarim said on Yud Tes Kislev begin with, and are based on this verse. -

Jewish Calendar

2018 - 2019 JEWISHThe JewishCALENDAR ART5779 CALENDAR A Gift To You From CALENDAR SPONSOR: CHABAD JEWISH CENTER OF MONROEVILLE 2715 Mosside Blvd. Monroeville, PA 15146 www.JewishMonroeville.com - Tel: 412-372-1000 - Fax: 877-563-5320 ב"ה THIS CALENDAR IS WISHING YOU... A HAPPY, HEALTHY HEALTHY HAPPY, A YOU... WISHING DEDICATED TO THE AND PROSPEROUS NEW YEAR! NEW PROSPEROUS AND LUBAVITCHER REBBE O.B.M., RABBI MENACHEM M. SCHNEERSOHN Wishing the Jewish Community a Happy, Healthy and Sweet New Year! His personal devotion to each and every individual Jew, as well, as his dedication to G-d and His Torah, continue to inspire the Chabad center here in Monroeville, PA. Dear Friend, With great pleasure we present this beautiful Jewish Art Calendar for the year 2018/2019 – 5779 our gift to you for the New Year. Mark & Sharon Abelman Pamela Martello A calendar is not merely a tool to keep us on track. Jewish tradition teaches that a Nathan & Myra Abromson Joseph & Sondra Mendlowitz calendar is much more than that. When our ancestors in Egypt had just begun to Tony & Sharon Battle Gilah & Michael Moritz taste the flavor of freedom, G-d gave them the first commandments, the first cables Marvin Birner Richard Myerowitz that connect us to Him. The very first Mitzvah was the instruction to sanctify time Tammy Blumenfeld, ILMO Neil Stuart & Ettie Oppenheimer itself by establishing the Jewish monthly cycle. Randy and Marsha Boswell Lisa Palmer It is this cycle that gives life and meaning to the entire year and to the lifecycle in Sherry Cartiff Bruce & Rochelle Parker general. -

“V'torah Yevakshu Mipihu,” Rabbi Sholom Dovber

@LKQBKQP THE ETERNAL HOUSE OF YAAKOV [CONT.] D’var Malchus | Likkutei Sichos Vol. 15, pg. 231-242 A DAILY DOSE OF MOSHIACH Moshiach & Geula EMOTIONS OR INTELLECT? Thought | Rabbi Yosef Karasik YAAKOV AVINU DID NOT DIE; HE LITERALLY LIVES IN A BODY Moshiach & Geula | Rabbi Sholom Dovber HaLevi Wolpo USA 744 Eastern Parkway ‘BINYAMIN, WHAT’S HAPPENING WITH Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409 Tel: (718) 778-8000 THE TANYA CLASSES?’ Fax: (718) 778-0800 Feature | Shai Gefen [email protected] www.beismoshiach.org EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: ‘BUT IF YOU STILL WANT TO FLY...’ M.M. Hendel Profile | Nosson Avrohom ENGLISH EDITOR: Boruch Merkur [email protected] HEBREW EDITOR: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE WORDS OF Rabbi Sholom Yaakov Chazan CHASSIDIM [email protected] Farbrengen Beis Moshiach (USPS 012-542) ISSN 1082- 0272 is published weekly, except Jewish holidays (only once in April and October) for PRINTING THE TANYA IN LEBANON $140.00 in the USA and in all other places for Feature | Shneur Zalman Berger $150.00 per year (45 issues), by Beis Moshiach, 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Periodicals postage paid at Brooklyn, NY and additional offices. Postmaster: send address changes to Beis FROM RUSSIA TO MOROCCO ON THE Moshiach 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Copyright 2007 by Beis REBBE’S SHLICHUS Moshiach, Inc. Chassid | Shneur Zalman Berger Beis Moshiach is not responsible for the content of the advertisements. A¤S>OJJ>I@ERP regular fear, such as fear of punishment, or even a lofty degree of fear. Rather, it is necessary to have perfect fear (lest he THE ETERNAL misconstrue the Supernal Will), which brings to the perfect conclusion regarding the law, the law in its ultimate truth. -

Torah Weekly

בס״ד TORAH WEEKLYParshat Korach 10 - 16 June, 2018 BUT WHY so well-intended and noble at THE REBBE: 27 Sivan - its core, albeit misguided, why 3 Tammuz, 5778 LEADERSHIP? was he punished? Was he even A BRIEF In this week’s Torah wrong? What is, in fact, the Torah : Portion we read a tragic story, role of a leader in the world of BIOGRAPHY Numbers 16:1 - 18:32 one in which many meet a Torah and Mitzvot? The Lubavitcher Reb- bitter end due to misguided The Lubavitcher Rebbe be, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Haftorah: behavior. This all begins when explains that the inherent Schneerson, of righteous me- Samuel I 11:14 - 12:22 a man named Korach attempts holiness of every single Jew mory (1902-1994), the seventh to lead a mutiny against the is indisputable. Every Jewish leader in the Chabad-Lubavitch leadership Moses and Aaron. man, woman and child pos- dynasty, is considered to have CALENDARS He claims, “All the people are sesses a spark of God Himself been the most phenomenal We have Jewish God’s chosen ones, all the pe- which can never be taken away. Jewish personality of modern Calendars, if you would ople are holy. Why should you It is for that reason that was a times. To hundreds of thou- like one, please send us and Aaron be exalted above Jew, any Jew, performs a Mi- sands of followers and millions a letter and we will send everyone else?” tzvah, he or she is introducing of sympathizers and admirers you one, or ask the Rab- Moses takes his claims additional Godly light in the around the world, he was — bi / Chaplain to contact to God and a face-off is set to world regardless of his or her and still is, despite his passing us. -

Chapter 51 the Tanya of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, Elucidated by Rabbi Yosef Wineberg Published and Copyrighted by Kehot Publication Society

Chapter 51 The Tanya of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi, elucidated by Rabbi Yosef Wineberg Published and copyrighted by Kehot Publication Society « Previous Next » Chapter 50 Chapter 52 The title-page of Tanya tells us that the entire work is based upon the verse (Devarim 30:14), “For this thing (the Torah) is very near to you, in your mouth and in your heart, that you may do it.” And the concluding phrase (“that you may do it”) implies that the ultimate purpose of the entire Torah is the fulfillment of the mitzvot in practice. In order to clarify this, ch. 35 began to explain the purpose of the entire Seder Hishtalshelut (“chain of descent” of spiritual levels from the highest emanation of the Creator down to our physical world), and of man’s serving G‑d. The purpose of both is to bring a revelation of G‑d’s Presence into this lowly world, and to elevate the world spiritually so that it may become a fitting dwelling-place for His Presence. To further explain this, ch. 35 quoted the words of the Yenuka in the Zohar that a Jew should not walk four cubits bareheaded because the Shechinah dwells above his head. This light of the Divine Presence, continues the Zohar, resembles the light of a lamp, where oil and wick are needed for the flame to keep burning. A Jew should therefore be aware, says the Zohar, of the Shechinah above him and keep it supplied with “oil” (good deeds), in order to ensure that the “flame” of the Shechinah keeps its hold on the “wick” (the physical body). -

1 Beginning the Conversation

NOTES 1 Beginning the Conversation 1. Jacob Katz, Exclusiveness and Tolerance: Jewish-Gentile Relations in Medieval and Modern Times (New York: Schocken, 1969). 2. John Micklethwait, “In God’s Name: A Special Report on Religion and Public Life,” The Economist, London November 3–9, 2007. 3. Mark Lila, “Earthly Powers,” NYT, April 2, 2006. 4. When we mention the clash of civilizations, we think of either the Spengler battle, or a more benign interplay between cultures in individual lives. For the Spengler battle, see Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996). For a more benign interplay in individual lives, see Thomas L. Friedman, The Lexus and the Olive Tree (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1999). 5. Micklethwait, “In God’s Name.” 6. Robert Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). “Interview with Robert Wuthnow” Religion and Ethics Newsweekly April 26, 2002. Episode no. 534 http://www.pbs.org/wnet/religionandethics/week534/ rwuthnow.html 7. Wuthnow, America and the Challenges of Religious Diversity, 291. 8. Eric Sharpe, “Dialogue,” in Mircea Eliade and Charles J. Adams, The Encyclopedia of Religion, first edition, volume 4 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 345–8. 9. Archbishop Michael L. Fitzgerald and John Borelli, Interfaith Dialogue: A Catholic View (London: SPCK, 2006). 10. Lily Edelman, Face to Face: A Primer in Dialogue (Washington, DC: B’nai B’rith, Adult Jewish Education, 1967). 11. Ben Zion Bokser, Judaism and the Christian Predicament (New York: Knopf, 1967), 5, 11. 12. Ibid., 375. -

Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery Vital Details 2019

Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery Vital Details 2019 Date of Date of Date of Birth Birth Death Date of Section Row Plot Image Gender Surname Given Father Mother Husband (Heb) (Secular) (Hebrew) Death (Sec) Age Language Shimon 60 60112 Adler Mirka Halewi Hebrew 2 Kislev 91 91027 Adlerstein 5695 Hebrew Yom Kippur 70 70057 Aharonowicz Malka Pesach 5694 Hebrew Shlomo 21 Iyyar 10 6730 Aharonzohn Zalman Aharon 5658 Hebrew 28 Jakob Cheshvan 24 8 Aijn Ajn Sheina Shmuel Halewi 5682 Hebrew Avraham 18 Adar 90 90049 Aijnbinder Ejtke Rachel Mordechai Josef 5698 Hebrew 9 Tevet 3 166 M Aijzenshmid Pinhas Yitzhak 5665/8 Hebrew Dwosze 8 Kislev 84 84023 Aijzensztadt Henia Zev 5692 Hebrew Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery Vital Details 2019 Aijzensztadt 67 67070 Ajzenstein Simcha Hebrew 10 Elul 1 1 17 5 M Aijzinsztadt Shmuel Tsvi Shabbatai 5676/7 Hebrew Chaim Lejb 25 Nisan Hebrew; 15 6330 Aijzinsztadt Hosha Hacohen Moshe 5666 9-Apr-06 Russian 9 Kislev 22 126 Aijzinsztadt Arieh Lejb Jakob 5693 62 Hebrew Shmuel 24 Kislev 9 425 M Ajger Eiger Josef Zundel Yehuda 5671 Hebrew 24 Elul 93 93121 Ajlbert Mashe Dabe Moshe Dov 5693 47 Hebrew 2 Tammuz 70 70008 Ajnotker(?) 5691 Hebrew 2 Shavuot 50 M Ajzenszmid Avraham Shmuel 5673 Hebrew 15 Cheshvan 15 6310 F Ajzensztadt Kreindel David 5665 Hebrew Bagnowka Jewish Cemetery Vital Details 2019 25 Adar I 26 26131 F Ajzensztadt Feiga Eliezer? 5668 Hebrew 27 Tammuz 49 F Ajzensztadt Keila Eliyahu 5663 Hebrew Michal 3 Adar 84 84043 Akes Joshua Simcha 5691 Hebrew 21 Tishri 12 3 5 4231 M Aleksandrowicz Mordechai Shmuel 5669 Hebrew Moshe 2 Tevet -

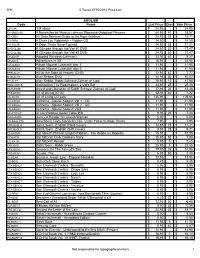

B"H 5 Teves 5775/2014 Price List ENGLISH Code Name List Price

B"H 5 Teves 5775/2014 Price List ENGLISH Code Name List Price Disc Sale Price EO-334I 334 Ideas $ 24.95 $ 24.95 EY-5NOV.SB 5 Novelettes by Marcus Lehman Slipcased (Adopted Princess, $ 64.95 40 $ 38.97 EF-60DA 60 Days Spiritual Guide to the High Holidays $ 24.95 25 $ 18.71 CD-DIRA A Dirah Loy Yisboraich - Yiddish CD $ 14.50 $ 14.50 EO-DOOR A Door That's Never Locked $ 14.95 25 $ 11.21 DVD-GLIM1 A Glimpse through the Veil #1 DVD $ 24.95 30 $ 17.47 DVD-GLIM2 A Glimpse through the Veil #2 DVD $ 24.95 30 $ 17.47 EY-ADOP Adopted Princess (Lehman) $ 13.95 40 $ 8.37 EY-ADVE Adventures in 3D $ 16.95 $ 16.95 CD-ALBU1 Album Nigunei Lubavitch disc 1 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ALBU2 Album Nigunei Lubavitch disc 2 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 ERR-ALLF All for the Sake of Heaven (CHS) $ 12.95 40 $ 7.77 DVD-ALTE Alter Rebbe, DVD $ 14.95 30 $ 10.47 EY-ALTE Alter Rebbe: Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi $ 19.95 10 $ 17.96 EMO-ANTI.S Anticipating The Redemption, 2 Vol's Set $ 33.95 25 $ 25.46 EAR-ARRE Arrest and Liberation of Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi $ 17.95 25 $ 13.46 ETZ-ARTO Art of Giving (CHS) $ 12.95 40 $ 7.77 CD-ARTO Art of Living CD sets $ 125.95 $ 125.95 CD-ASHR1 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol 1 - CD $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ASHR2 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol 2 - CD $ 11.95 $ 11.95 CD-ASHR3 Ashreinu...Sipurei Kodesh Vol3 $ 11.95 $ 11.95 EP-ATOU.P At Our Rebbes' Seder Table P/B $ 9.95 25 $ 7.46 EWO-AURA Aura - A Reader On Jewish Woman $ 5.00 $ 5.00 CD-BAALSTS Baal Shem Tov's Storyteller CD - Uncle Yossi Heritage Series $ 7.95 $ 7.95 EFR-BASI.H Basi L'Gani - English (Hard Cover) -

Calendar 2017-2018/5777-5778

Calendar 2017-2018/5777-5778 SHOWCASING SOME OF THE AGENCIES AND PROGRAMS SUPPORTED BY THE ASSOCIATED: JEWISH COMMUNITY FEDERATION OF BALTIMORE OUR ANNUAL CAMPAIGN AT WORK o m Missionn The Associated: Jewish Community Federation of Baltimore strengthens and nurtures Jewish life by engaging and supporting community partners in Greater Baltimore, Israel and around the world. b Vision m The Associated will secure the resources necessary to address the evolving landscape of Jewish life, ensuring a vibrant mcommunity for future ngenerations. 2017/2018 We like to think that when it comes to the Jewish community, we are here for each other. Every hour of every day, thanks to the generosity of you, our trustedb donors and fellow community members, The Associated: Jewish Community Federation of Baltimore, its agencies and programs, are here to nurture and support Jewish life in Baltimore neighborhoods and around the world. We are in Federal Hill and in Pikesville. We are in Reisterstown and Towson. And we are in all the communities in between where there are individuals and families who need a helping hand or are searching for meaningful Jewish experiences. The stories that unfold on these pages represent the scope of The Associated system’s services and highlight the people and the neighborhoods where we are making a difference. We showcase stories of inspiration and hope as well as stories of how we build strong Jewish identity for our next generation. Whether it’s connecting Jewish families living downtown, providing a “Big Sister” to help a young girl gain her self-esteem or offering a wide array of opportunities for seniors to live productive and happy lives, we strengthen Jewish community each and every day.