Applied Anthropology and Anti-Hate Activism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identitarian Movement

Identitarian movement The identitarian movement (otherwise known as Identitarianism) is a European and North American[2][3][4][5] white nationalist[5][6][7] movement originating in France. The identitarians began as a youth movement deriving from the French Nouvelle Droite (New Right) Génération Identitaire and the anti-Zionist and National Bolshevik Unité Radicale. Although initially the youth wing of the anti- immigration and nativist Bloc Identitaire, it has taken on its own identity and is largely classified as a separate entity altogether.[8] The movement is a part of the counter-jihad movement,[9] with many in it believing in the white genocide conspiracy theory.[10][11] It also supports the concept of a "Europe of 100 flags".[12] The movement has also been described as being a part of the global alt-right.[13][14][15] Lambda, the symbol of the Identitarian movement; intended to commemorate the Battle of Thermopylae[1] Contents Geography In Europe In North America Links to violence and neo-Nazism References Further reading External links Geography In Europe The main Identitarian youth movement is Génération identitaire in France, a youth wing of the Bloc identitaire party. In Sweden, identitarianism has been promoted by a now inactive organisation Nordiska förbundet which initiated the online encyclopedia Metapedia.[16] It then mobilised a number of "independent activist groups" similar to their French counterparts, among them Reaktion Östergötland and Identitet Väst, who performed a number of political actions, marked by a certain -

Galilee Flowers

GALILEE FLOWERS The Collected Essays of Israel Shamir Israel Adam Shamir GALILEE FLOWERS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 5 WHY I SUPPORT THE RETURN OF PALESTINIANS.................................................................... 6 PART ONE....................................................................................................................................... 8 THE STATE OF MIND ................................................................................................................. 8 OLIVES OF ABOUD.................................................................................................................... 21 THE GREEN RAIN OF YASSOUF................................................................................................ 23 ODE TO FARRIS ........................................................................................................................ 34 THE BATTLE FOR PALESTINE.................................................................................................. 39 THE CITY OF THE MOON ......................................................................................................... 42 JOSEPH REVISITED................................................................................................................... 46 CORNERSTONE OF VIOLENCE.................................................................................................. 50 THE BARON’S BRAID............................................................................................................... -

FUNDING HATE How White Supremacists Raise Their Money

How White Supremacists FUNDING HATE Raise Their Money 1 RESPONDING TO HATE FUNDING HATE INTRODUCTION 1 SELF-FUNDING 2 ORGANIZATIONAL FUNDING 3 CRIMINAL ACTIVITY 9 THE NEW KID ON THE BLOCK: CROWDFUNDING 10 BITCOIN AND CRYPTOCURRENCIES 11 THE FUTURE OF WHITE SUPREMACIST FUNDING 14 2 RESPONDING TO HATE How White Supremacists FUNDING HATE Raise Their Money It’s one of the most frequent questions the Anti-Defamation League gets asked: WHERE DO WHITE SUPREMACISTS GET THEIR MONEY? Implicit in this question is the assumption that white supremacists raise a substantial amount of money, an assumption fueled by rumors and speculation about white supremacist groups being funded by sources such as the Russian government, conservative foundations, or secretive wealthy backers. The reality is less sensational but still important. As American political and social movements go, the white supremacist movement is particularly poorly funded. Small in numbers and containing many adherents of little means, the white supremacist movement has a weak base for raising money compared to many other causes. Moreover, ostracized because of its extreme and hateful ideology, not to mention its connections to violence, the white supremacist movement does not have easy access to many common methods of raising and transmitting money. This lack of access to funds and funds transfers limits what white supremacists can do and achieve. However, the means by which the white supremacist movement does raise money are important to understand. Moreover, recent developments, particularly in crowdfunding, may have provided the white supremacist movement with more fundraising opportunities than it has seen in some time. This raises the disturbing possibility that some white supremacists may become better funded in the future than they have been in the past. -

Wahrheit Sagen, Teufel Jagen

Das Original in Englisch: Wahrheit sagen, Teufel jagen ISBN 978- 1 – 937787 – 29 – 5 Gerard Menuhin Copyright 2015: GERARD MENUHIN und THE BARNES REVIEW Veröffentlichung durch: THE BARNES REVIEW, P.O. Box 15877, Washington, D.C. 20003 Die amerikanische Originalausgabe erschien unter dem Titel „Tell the Truth & Shame the Devil“ 2015 THE BARNES REVIEW. >>>>bumibahagia.com<<<< Übersetzung aus dem Amerikanischen von Jürgen Graf. Die Wiedergabe von russischen Eigennamen erfolgte nach Duden-Transkription. HINWEIS: Diese PDF-Datei ist keine offizielle Veröffentlichung! Bitte unterstützen Sie den Autor und erwerben Sie das Originalbuch. Weitere Hinweise am Ende! „Ich mache das vom englischen Original auf Deutsch übersetzte Buch online zugänglich, da ich meine Botschaft dringendst verbreiten möchte und die deutsche gedruckte Fassung auf sich warten lässt. Die Seite bumi bahagia (indonesisch, glückliche Erde) scheint mir bestens dafür geeignet, da ich glaube, dass deren Betreiber Thom Ram die gleichen Hoffnungen für die Menschheit hegt wie ich.“ -Gerard Menuhin- Widmung: Für Deutschland. Für Deutsche, die es noch sein wollen. Für die Menschheit. Wahrheit sagen, Teufel jagen Wie ein alter kleiner Mann im karierten Hemd zum Autor sprach Autor: Gerard Menuhin „Trauer ist Wissen; jene, die am meisten wissen, müssen angesichts der verhängnisvollen Wahrheit am tiefsten trauern, denn der Baum der Erkenntnis ist nicht jener des Lebens.“ – Byron, „Manfred“ Inhalt: Kapitel I - Vereitelt: Der letzte verzweifelte Griff der Menschheit nach Freiheit Kapitel II - Identifiziert: Illumination oder die Diagnose der Finsternis Kapitel III - Ausgelöscht: Zivilisation Kapitel IV - Endstadium: Das kommunistische Vasallentum Kapitel I Vereitelt: Der letzte verzweifelte Griff der Menschheit nach Freiheit Dieser Hund ist ein Labrador. Er bellt nur selten und ist gutmütig, wie die meisten Labradore. -

CRIMINAL COMPLAINT, UNITED STATES of AMERICA V. WILLIAM

AO 91 (REV.5/85) Criminal Complaint AUSA MICHAEL FERRARA, (312) 886-7649 W4444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444444 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ILLINOIS, EASTERN DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA CRIMINAL COMPLAINT v. WILLIAM WHITE CASE NUMBER: Under Seal I, the undersigned complainant being duly sworn state the following is true and correct to the best of my knowledge and belief. On or about September 11, 2008, in Cook County, in the Northern District of Illinois, Eastern Division, and elsewhere, the defendant: with intent that another person engage in conduct constituting a felony that has as an element the use, attempted use, or threatened use of force against the person of Hale Juror A in violation of the laws of the United States, and under circumstances strongly corroborative of that intent, solicited and otherwise attempted to persuade such other person to engage in such conduct; in that defendant solicited and otherwise attempted to persuade another person to injure Hale Juror A on account of a verdict assented to by Hale Juror A, in violation of Title 18, United States Code Section 1503; all in violation of Title 18, United States Code, Section 373. I further state that I am a Special Agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation and that this complaint is based on the following facts: PLEASE SEE ATTACHED AFFIDAVIT. Continued on the attached sheet and made a part hereof: X Yes No Maureen Mazzola, Special Agent Federal Bureau of Investigation Sworn to before me and subscribed in my presence, October 17, 2008 at Chicago, Illinois Date City and State Susan E. -

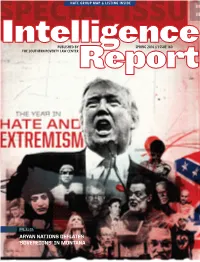

Aryan Nations Deflates

HATE GROUP MAP & LISTING INSIDE PUBLISHED BY SPRING 2016 // ISSUE 160 THE SOUTHERN POVERTY LAW CENTER PLUS: ARYAN NATIONS DEFLATES ‘SOVEREIGNS’ IN MONTANA EDITORIAL A Year of Living Dangerously BY MARK POTOK Anyone who read the newspapers last year knows that suicide and drug overdose deaths are way up, less edu- 2015 saw some horrific political violence. A white suprem- cated workers increasingly are finding it difficult to earn acist murdered nine black churchgoers in Charleston, S.C. a living, and income inequality is at near historic lev- Islamist radicals killed four U.S. Marines in Chattanooga, els. Of course, all that and more is true for most racial Tenn., and 14 people in San Bernardino, Calif. An anti- minorities, but the pressures on whites who have his- abortion extremist shot three people to torically been more privileged is fueling real fury. death at a Planned Parenthood clinic in It was in this milieu that the number of groups on Colorado Springs, Colo. the radical right grew last year, according to the latest But not many understand just how count by the Southern Poverty Law Center. The num- bad it really was. bers of hate and of antigovernment “Patriot” groups Here are some of the lesser-known were both up by about 14% over 2014, for a new total political cases that cropped up: A West of 1,890 groups. While most categories of hate groups Virginia man was arrested for allegedly declined, there were significant increases among Klan plotting to attack a courthouse and mur- groups, which were energized by the battle over the der first responders; a Missourian was Confederate battle flag, and racist black separatist accused of planning to murder police officers; a former groups, which grew largely because of highly publicized Congressional candidate in Tennessee allegedly conspired incidents of police shootings of black men. -

The Bates Student

Bates College SCARAB The aB tes Student Archives and Special Collections 4-13-1932 The aB tes Student - volume 60 number 01 - April 13, 1932 Bates College Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student Recommended Citation Bates College, "The aB tes Student - volume 60 number 01 - April 13, 1932" (1932). The Bates Student. 488. http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student/488 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aB tes Student by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ?3 FOUNDED BOWDOIN GAME IN 1873 tnhmi ON TUESDAY PRICE TEN CENTS VOL LX No. 1 LEWISTON, .MAINE, WEDNESDAY, APRIL 13, 1932 *Q1 » # F R O M ' Bates Violinist School Debaters RUSSIA IMPRESSES EX-GOV. BAXTER; DISARMAMENT DISCUSSED BY SEES REBIRTH ON 7,000-MILE TRIP T ] HL E DR. BROWN OF PRINCETON On Program At Have Semi-Finals Former Governor Percival P. Baxter has just completed a N E w S 7,090-mile trip of 34 days duration through the Soviet Union X5 under the auspices of the Soviet Tourist bureau. In a wireless- IN CLOSING CHASE LECTURE Auburn Theatre Friday Evening gram to the New York Times dated April 7 telling of his expe- jn order that our reader! may have the opportunity of forming a Winners to Meet for riences. Mr. Baxter said : Declares Urgent Need of Today Is Universal dear Idea of t'.ie controversy at Norman DeMarco, '34 "The journey was immensely impressive, not only on Adjustment—Believes Outlook For Peace Columbia which has centered about Finals Saturday account of the diversity of scenes and people, but because of the the expulsion of Reed Haris, editor To Begin 3-Day En- Not Entirely Drap of Spectator, the Student is quoting Morning evidences of energy, enthusiasm and constructive work. -

How White Supremacists Raise Their Money

Funding Hate: How White Supremacists Raise Their Money Sections 1 Introduction 5 The New Kid on the Block: Crowdfunding 2 Self-Funding 6 Bitcoin and Cryptocurrencies 3 Organizational Funding 7 The Future of White Supremacist Funding 4 Criminal Activity INTRODUCTION t’s one of the most frequent questions the Anti-Defamation League gets asked: I Where do white supremacists get their money? 1 / 19 Implicit in this question is the assumption that white supremacists raise a substantial amount of money, an assumption fueled by rumors and speculation about white supremacist groups being funded by sources such as the Russian government, conservative foundations, or secretive wealthy backers. The reality is less sensational but still important. As American political and social movements go, the white supremacist movement is particularly poorly funded. Small in numbers and containing many adherents of little means, the white supremacist movement has a weak base for raising money compared to many other causes. Moreover, ostracized because of its extreme and hateful ideology, not to mention its connections to violence, the white supremacist movement does not have easy access to many common methods of raising and transmitting money. This lack of access to funds and funds transfers limits what white supremacists can do and achieve. However, the means by which the white supremacist movement does raise money are important to understand. Moreover, recent developments, particularly in crowdfunding, may have provided the white supremacist movement with more fundraising opportunities than it has seen in some time. This raises the disturbing possibility that some white supremacists may become better funded in the future than they have been in the past. -

Palimpsest World: the Serpentine Trail of Roy Frankhouser from the SWP, the KKK, and the “Knights of Malta” to Far Beyond the Grassy Knoll1

1 Palimpsest World: The Serpentine Trail of Roy Frankhouser from the SWP, the KKK, and the “Knights of Malta” to Far Beyond the Grassy Knoll1 Introduction In the summer of 1987 the National Caucus of Labor Committees (NCLC) submitted a document in a legal action that attempted to prove that Roy Frankhouser, a well-known KKK member and Lyndon LaRouche‘s longtime paid ―security consultant,‖ was highly connected inside the CIA. The document, ―Attachment 2,‖ began: During 1974-75, Roy Frankhauser [sic], claiming to be working on behalf of the CIA, established contact with the NCLC. In approximately June 1975, Frankhauser submitted to three days of intensive debriefings, during which time he provided details of his employment with the National Security Council on a special assignment to penetrate a Canada-based cell of the Palestinian terrorist Black September organization, and other aspects of his CIA career dating back to his involvement in the Bay of Pigs.2 Frankhauser said he served as the ―babysitter‖ for [Mario] Garcia- Kholy [sic], one of the Brigade leaders who was to have a high government post in a post-Castro Cuba.3 Subsequently, NCLC researchers found a brief reference in PRAVDA citing a 1962 expulsion of one ―R. Frankhauser‖ from a low-level post at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow on charges that he was spying.4 The NCLC reference to a ―R. Frankhauser‖ being in Moscow in 1962 as somehow relevant evidence that Roy E. Frankhouser was working for the CIA suggests just how much we have entered the Mad Hatter‘s World. -

JANUARY 31, 1986 35E PER COPY

Rhode Island Jewish 1 Historical Assoc. 136 Sessions st. Inside: Prov. R.I. 02906 Israel Travel Supplement THE ONLY ENGLISH-JEWISH WEEKLY IN R.J. AND SOUTHEAST MASS. VOLUME LXXIII, NUMBER 8 FRIDAY, JANUARY 31, 1986 35e PER COPY Leonard Bernstein At 67 Seeing Ourselves In The by Benjamin Ivry proven wrong by the young conductor's Eyes Of The Homeless (.JSPS) As surely as Leonard sensational debut. conducting the New Bernstein ·s birthday rolls around, the York Philharmonic just over forty years diatribes aga inst him appear. Bernstein ago. has not "fulfilled his promise." complain Bernstein has always been in love with the music cri tics drily. His gifts. they feel. the Hebrew language, dating back to his are displayed too sloppily. .. Kaddish Symphony" No. :l. with it In fact. Leonard Bernstein has avoided setting of the Hebrew words. Another ~ the neat pigeonholes of mediocrity. He has notable example is his "Chicheter Psalms" maintained over the years separate careers ( 1966). This choral wo rk was written fo r a~ composer of pop and classical music, the Chichester Cathedral Music Festiva l. \ \ conductor. teacher. author, and amateur The English clergymen must have been A ~ political spokesman. su rprised t.o find that the Psalms would be ~ , : Bernstein ·s devotion to Israel and to sung . in Hebrew, at the composer's ~ American .Judaism is beyond question. He insistence, rather than in the more -~ t:;'i, has conducted the Israel Philharmonic. familiar Latin. since the days when they we re the However, Leonard Bernstein refuses to -. Palestine Philharmonic. He was back on be the ".Jewish conductor" some demand. -

Fleurs De Galilée (Recueil D’Articles 2001-2002)

Israel Adam Shamir Fleurs de Galilée (Recueil d’articles 2001-2002) Traduction française par les amis de Shamir http://www.israelshamir.net/French/fleursdegalilee.html Table des Matières Avant-propos 003 Pourquoi je défends le droit au retour des Palestiniens 004 Partie 1 – ‘L’état’ (d’esprit) 006 – Les oliviers d’Abour 016 – La pluie verte de Yassouf 018 – Ode à Farès ou le retour du Chevalier 028 – La bataille de Palestine 032 – La ville de la lune 034 – Ce qui s'est vraiment passé au tombeau de Joseph 037 – Première pierre de la violence 040 – La tresse du baron 045 – L’invasion 050 – Convoi pour Bethléem 053 – Les héros de la dernière chance 056 – Les collines de Judée 059 Partie 2 – La Galilée en fleurs 061 – Le réservoir de Mamilla 064 – Avril est le mois le plus cruel 071 – Encore un plan de paix 074 Partie 3 – L’épreuve était décisive 076 – Le viol de Dulcinée 079 – La rengaine des deux Etats 081 – Le fou d’été et le fou d’hiver 087 Partie 4 – Elle est vraiment impossible cette petite sœur ! 090 – La nouvelle complainte de Portnoy 091 – Dans une certaine mesure 097 – Le bal des vampires 100 – Banquiers et voleurs 104 – 27 juillet, Fête de Saint Firmin 111 – Le nigaud de service 115 – Le prince charmant 117 – Orient Express 125 – Derniers feux de l’été 127 Partie 5 – Une Medina yiddish 132 – Les Sages de Sion et les Maîtres du Discours 153 – Les Juifs et les Protocoles 158 – Une cour assidue mais vaine 162 – La vague de réfugiés est en marche 166 – Le moineau et le scarabée 175 Partie 6 – Guerriers et gynécée 181 – L’empoisonnement -

The Domestic Terrorist Threat: Background and Issues for Congress

The Domestic Terrorist Threat: Background and Issues for Congress Jerome P. Bjelopera Specialist in Organized Crime and Terrorism January 17, 2013 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov R42536 CRS Report for Congress Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress The Domestic Terrorist Threat: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The emphasis of counterterrorism policy in the United States since Al Qaeda’s attacks of September 11, 2001 (9/11) has been on jihadist terrorism. However, in the last decade, domestic terrorists—people who commit crimes within the homeland and draw inspiration from U.S.-based extremist ideologies and movements—have killed American citizens and damaged property across the country. Not all of these criminals have been prosecuted under terrorism statutes. This latter point is not meant to imply that domestic terrorists should be taken any less seriously than other terrorists. The Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) do not officially list domestic terrorist organizations, but they have openly delineated domestic terrorist “threats.” These include individuals who commit crimes in the name of ideologies supporting animal rights, environmental rights, anarchism, white supremacy, anti-government ideals, black separatism, and anti-abortion beliefs. The boundary between constitutionally protected legitimate protest and domestic terrorist activity has received public attention. This boundary is especially highlighted by a number of criminal cases involving supporters of animal rights—one area in which specific legislation related to domestic terrorism has been crafted. The Animal Enterprise Terrorism Act (P.L. 109-374) expands the federal government’s legal authority to combat animal rights extremists who engage in criminal activity.