Seeing with Their Investments, Minds, and Hearts: Relief After the Great

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of the City of Chicago Flag

7984 S. South Chicago Ave. - Chicago, IL 60616 Ph: 773-768-8076 Fx: 773-768-3138 www.wgnflag.com The History of the City of Chicago Flag In 1915, Alderman James A Kearns proposed to the city council that Chicago should have a flag. Council approved the proposal and established the Chicago Flag Commission to consider designs for the flag. A contest was held and a prize offered for the winning design. The competition was won by Mr. Wallace Rice, author and editor, who had been interested in flags since his boyhood. It took Mr. Rice no less than six weeks to find a suitable combination of color, form, and symbolism. Mr. Rice’s design was approved by the city council in the summer of 1917. Except for the addition of two new stars—one in 1933 commemorating “the Century of Progress” and one in 1939 commemorating Fort Dearborn—the flag remains unchanged to this day. In explaining some of the symbolism of his flag design, Mr. Rice says: It is white, the composite of all colors, because its population is a composite of all nations, dwelling here in peace. The white is divided into three parts—the uppermost signifying the north side, the larger middle area the great west side with an area and population almost exceeding that of the other two sides, and the lowermost, the south side. The two stripes of blue signify, primarily, Lake Michigan and the north Chicago River above, bounding the north side and south branch of the river and the great canal below. -

The Great Chicago Fire

rd 3 Grade Social Sciences ILS—16A, 16C, 16D, 17A The Great Chicago Fire How did the Great Chicago Fire of October 1871 change the way people designed and constructed buildings in the city? Vocabulary This lesson assumes that students already know the basic facts about the Chicago Fire. The lesson is designed to help students think about what happened after the load-bearing method a method of fire died out and Chicagoans started to rebuild their city. construction where bricks that form the walls support the structure Theme skeleton frame system a method This lesson helps students investigate how the fire resulted in a change of the of construction where a steel frame construction methods and materials of buildings. By reading first-hand accounts, acts like the building’s skeleton to support the weight of the structure, using historic photographs, and constructing models, students will see how the and bricks or other materials form the people of Chicago rebuilt their city. building’s skin or outer covering story floors or levels of a building Student Objectives • write from the point of view of a person seen in photographs taken shortly after conflagration a large destructive fire the Great Chicago Fire • point of view trying to imagine distinguish between fact and opinion Grade Social Sciences how another person might see or rd • differentiate between a primary source and a secondary source 3 understand something • discover and discuss the limitations and potential of load-bearing and skeleton frame construction methods primary source actual -

Streeterville Neighborhood Plan 2014 Update II August 18, 2014

Streeterville Neighborhood Plan 2014 update II August 18, 2014 Dear Friends, The Streeterville Neighborhood Plan (“SNP”) was originally written in 2005 as a community plan written by a Chicago community group, SOAR, the Streeterville Organization of Active Resi- dents. SOAR was incorporated on May 28, 1975. Throughout our history, the organization has been a strong voice for conserving the historic character of the area and for development that enables divergent interests to live in harmony. SOAR’s mission is “To work on behalf of the residents of Streeterville by preserving, promoting and enhancing the quality of life and community.” SOAR’s vision is to see Streeterville as a unique, vibrant, beautiful neighborhood. In the past decade, since the initial SNP, there has been significant development throughout the neighborhood. Streeterville’s population has grown by 50% along with new hotels, restaurants, entertainment and institutional buildings creating a mix of uses no other neighborhood enjoys. The balance of all these uses is key to keeping the quality of life the highest possible. Each com- ponent is important and none should dominate the others. The impetus to revising the SNP is the City of Chicago’s many new initiatives, ideas and plans that SOAR wanted to incorporate into our planning document. From “The Pedestrian Plan for the City”, to “Chicago Forward”, to “Make Way for People” to “The Redevelopment of Lake Shore Drive” along with others, the City has changed its thinking of the downtown urban envi- ronment. If we support and include many of these plans into our SNP we feel that there is great- er potential for accomplishing them together. -

The Great Chicago Fire, Described in Seven Letters by Men and Women

®mn . iFaiB The uman Account as descriDecUpp^e-witnesses in seven r i []!. letters written by men and women who experienced its terrors With PAUL M. ANGLE $3.00 THE GREAT CHICAGO FIRE ******** Here is the Great Chicago Fire of 1871— the catastrophe which, in little more than twenty-four hours, took 300 lives, left 90,000 people homeless, and destroyed property worth $200,000,000—described in letters written by men and women who lived through it. Written during the Fire and immedi- ately afterward, these artless letters convey the terrors of the moment—flame-swept streets, anguished crowds, buildings that melted in minutes—with a vividness that no reader can forget. There may be more scholarly, more comprehensive accounts of Chicago's Great Fire, but none approaches this in realism that is almost photographic. Edited, with Introduction and Notes, by Paul M. Angle, Director, The Chicago Historical Society. Published by the Society in commemoration of the seventy-fifth an- niversary of the Fire. THE GREAT CHICAGO EIRE m '' "-. ' . '' ifi::-;5?jr:::^:; '-; .] .'."' : "' ;; :"". .:' -..;:,;'.:, 7: LINCOLN ROOM UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS LIBRARY MEMORIAL the Class of 1901 founded by HARLAN HOYT HORNER and HENRIETTA CALHOUN HORNER Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/greatchicagofireOOangl "=VI The Great Chicago Fire decorated by Joseph Trautwein fgqis (cm3(CA<a(D DESCRIBED IN SEVEN LETTERS BY MEN AND WOMEN WHO EXPERIENCED ITS HORRORS, AND NOW PUBLISHED IN COM- MEMORATION OF THE SEVENTY-FIFTH ANNIVERSARY OF THE CATASTROPHE Introduction and Notes by Paul M. -

Property Rights in Reclaimed Land and the Battle for Streeterville

Columbia Law School Scholarship Archive Faculty Scholarship Faculty Publications 2013 Contested Shore: Property Rights in Reclaimed Land and the Battle for Streeterville Joseph D. Kearney Thomas W. Merrill Columbia Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Environmental Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Joseph D. Kearney & Thomas W. Merrill, Contested Shore: Property Rights in Reclaimed Land and the Battle for Streeterville, 107 NW. U. L. REV. 1057 (2013). Available at: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/383 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Scholarship Archive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Archive. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright 2013 by Northwestern University School of Law Printed in U.S.A. Northwestern University Law Review Vol. 107, No. 3 Articles CONTESTED SHORE: PROPERTY RIGHTS IN RECLAIMED LAND AND THE BATTLE FOR STREETERVILLE Joseph D. Kearney & Thomas W. Merrill ABSTRACT-Land reclaimed from navigable waters is a resource uniquely susceptible to conflict. The multiple reasons for this include traditional hostility to interference with navigable waterways and the weakness of rights in submerged land. In Illinois, title to land reclaimed from Lake Michigan was further clouded by a shift in judicial understanding in the late nineteenth century about who owned the submerged land, starting with an assumption of private ownership but eventually embracing state ownership. The potential for such legal uncertainty to produce conflict is vividly illustrated by the history of the area of Chicago known as Streeterville, the area of reclaimed land along Lake Michigan north of the Chicago River and east of Michigan Avenue. -

Brand Lookbook

2017-2018 LOOKBOOK WE VALUE EVERY PERSON WHO AUDIENCE VISITS, CALLS, OR WRITES TO OUR OFFICES EVERY MEMBER OF OUR TEAM WHO IS COMMITTED TO SERVING OUR CITY EVERY COMMUNITY PARTNER WHO IS DEDICATED TO IMPROVING OUR CITY EVERY VOLUNTEER WHO GIVES THEIR TIME FOR THE BETTERMENT OF OUR CITY EVERY CHICAGOAN 2 Brand Guidelines | Audience brand colors CMYK 0 98 95 0 RGB 237 33 39 PMS 485 C RED HEX# ED2127 CMYK 0 0 0 0 RGB 255 255 255 HEX# ffffff CMYK 99 81 15 3 RGB 25 74 141 WHITE PMS 301 C HEX# 194A8D CMYK 83 6 96 0 RGB 0 166 81 PMS 354 C BLUE HEX# 00A651 color usage CMYK Printing RGB Printing PMS Printing GREEN HEX Web, On-Screen Brand Guidelines | Audience Brand Guidelines | Brand Colors 3 LOGO Our logo embodies the history, future and community of Chicago. The history of Chicago is the heart of our brand. The 4 layers of stars within our logo represent the 4 stars of the official Chicago flag. The 4 stars within the flag represent Fort Dearborn, the Great Chicago Fire, the World’s Columbian Exposition and a Century of Progress. The colors red, white and blue tell the story of Chicago. Red represents the municipal identity of Chicago. White represents the diverse union of communities in Chicago. Blue represents the north and south branch of the Chicago River. The future of Chicago pushes our brand to be better. The color green within our logo represents growth, vitality and community. Chicago is evolving and our brand is evolving along with it. -

Chicago Chicago

Top places to go, where to eat, what to drink, on a budget, how to get there… a guide to your stay in Chicago! Chicago Top Attractions 1. Art institute of Chicago Voted #1 Museum in the World 2. Cloud Gate; Anish Kapoor sculpture in Millennium Park 3. Millennium Park; architecture, sculpture and landscape design 4. Museum of Contemporary Art 5. Lakefront Trail 6. Willis Tower 7. Chicago Cubs Game @ashleyliebig has organised a #smaccball block for the Monday night. The block is sold out but still plenty of tickets for the game. 8. Richard H Driehaus Museum Cloud Gate Millennium Park 9. Museum of Science/Industry Chicago Getting Around 1. From the Airport Taxis; $40-$50 GO Airport Express Buses 2. Around Chicago Chicago Transit Authority (transitchicago.com) – ‘L trains”, buses. Unlimited Ride Passes 1 day $5.75 3 day $14 7 day $23 Taxis $2.25 for first 1/9th mile and 20c thereafter Chicago Shopping 1. The Magnificent Mile 2. Jazz Record Mart Probably the largest jazz and blues store in the country, if not the world. A must stop for anyone with an interest in either genre. 3. Water Tower Place Walking distance from the Sheraton 4. Adagio Teas 5. Myopic Books 6. American Girl Place (in water tower place) 7. French Market 8. Vosges Haut-Chocolat The Magnificent Mile, Michigan Ave Chicago Ingest and Imbibe 1. Restaurants Top end; Alinea, Girl and the Goat, Table 52, Topolobampo Fabulous Italian; Nico Osteria, Tratorria No 10, Eataly Steak; Gibson Steak House Pizza; Lou Malnati’s Pizzeria: Deep Dish Pizza Tapas; Iberico, Mercat a la Planxa Hotdogs; Portillo’s, Superdawg 2. -

Color Map Layout.Indd

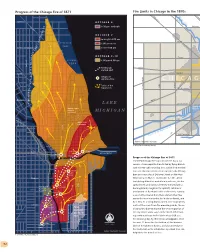

Map 29b • Fire extent TO PRESS 25 Sep 03 DESIGNER: Map 29b has been modified to go across the gutter so it can accompany map 29a (dark Fire map) This shorter version of Map 29b sacrifices relatively little content, if you need the room for captions Irving Park ��������������������������������������� L A K E onV I E Wthis spread ������������������������������������ Fire Limits in Chicago in the 1870s Belmont Lincoln Clark Milwaukee Ch ic a Elston g o ��������� R � � � � � � � � � i ver City limits in 1871 ������ Fullerton � ���������������� Built-up area in 1871 � � Lincoln Area burned in fire � Park � “Fire Limits” � � � � � � � � � � area where � � 1872 ordinance ���������������� � restricted building North � materials � � � � � � � ������������ � � � � � � ����������������� � ������������ � � ����� � DESTROYED � � ����������� � BY FIRE � Chicago � � � � � � � ��������������� � � � � � � ������� � ���������� � � ������������� Business � Madison District ����� � � ���������� ) LAKE � �������������� CHICAGO � d � e ve (Pulaski e ������������� stern M ICHIGAN � Stat Kedzi ��������� We Ashland Halste � 12th (Roosevelt) 40th A � � � � � gden �������� � O � � � � � � 22nd (Cermak) Lumber ������������ District ��������� ���������� � � � � � � � � ����� 31st ����������� ���������� Union ������� ��� Stock �� Yard an Canal ichig O N E M I L E & M 39th (Pershing) Illinois Author: Michael P. Conzen © 2004 The Newberry Library Mason (47th) 47th ������� ������� ������ ���������������� ������� H Y D E P ARK ������������� Progress of the Chicago Fire -

Accidents and Disasters in the U.S. and the World 512:235 Monday/Thursday 11:30-12:50 Frelinghuysen Hall B6, College Ave

Accidents and Disasters in the U.S. and the World 512:235 Monday/Thursday 11:30-12:50 Frelinghuysen Hall B6, College Ave. Campus Prof. Jamie Pietruska <[email protected]> Office: Van Dyck 311 Office phone: 848.932.8544 Office hours: TBA or by appointment Course Description This course examines the histories of accidents and disasters in the United States and the world from the 17th to the 21st centuries, with particular emphasis on the 19th and 20th centuries. Although accidents and disasters are often understood as isolated, rare events, catastrophic events have been continuously important to the history of the United States, both at home and abroad, for the past four centuries. Through ongoing efforts to anticipate unforeseen dangers, develop new tools for risk management, build infrastructures for relief, expand the capacity of the state for disaster response, and remember victims, accidents and disasters have become increasingly central to everyday life in the United States. The course will revolve around four sets of questions: 1.) To what extent are “natural” disasters, like hurricanes and floods, in fact “unnatural”— 2 shaped by human decisions about markets and economic growth, science and technology, and governance? Conversely, to what extent are the failures of human-built technological systems like nuclear reactors and electrical grids beyond human control? 2.) How can historians understand singular events—like the Great Chicago Fire (1871) and the San Francisco Earthquake (1906), and high-profile accidents like Chernobyl -

Illinois Military Museums & Veterans Memorials

ILLINOIS enjoyillinois.com i It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far nobly advanced. Abraham Lincoln Illinois State Veterans Memorials are located in Oak Ridge Cemetery in Springfield. The Middle East Conflicts Wall Memorial is situated along the Illinois River in Marseilles. Images (clockwise from top left): World War II Illinois Veterans Memorial, Illinois Vietnam Veterans Memorial (Vietnam Veterans Annual Vigil), World War I Illinois Veterans Memorial, Lincoln Tomb State Historic Site (Illinois Department of Natural Resources), Illinois Korean War Memorial, Middle East Conflicts Wall Memorial, Lincoln Tomb State Historic Site (Illinois Office of Tourism), Illinois Purple Heart Memorial Every effort was made to ensure the accuracy of information in this guide. Please call ahead to verify or visit enjoyillinois.com for the most up-to-date information. This project was partially funded by a grant from the Illinois Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity/Office of Tourism. 12/2019 10,000 What’s Inside 2 Honoring Veterans Annual events for veterans and for celebrating veterans Honor Flight Network 3 Connecting veterans with their memorials 4 Historic Forts Experience history up close at recreated forts and historic sites 6 Remembering the Fallen National and state cemeteries provide solemn places for reflection is proud to be home to more than 725,000 8 Veterans Memorials veterans and three active military bases. Cities and towns across the state honor Illinois We are forever indebted to Illinois’ service members and their veterans through memorials, monuments, and equipment displays families for their courage and sacrifice. -

The Chicago Shoreline Originally Consisted of a Natural Sand Edge, with Dunes and Swales and Marshy Lowlands

The Chicago shoreline originally consisted of a natural sand edge, with dunes and swales and marshy lowlands. Prior to the 1770s, the area was primarily inhabited by native American Indians. As the shipping industry grew and water-borne travel increased from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River, via the Chicago, des Plaines, and Illinois Rivers, the importance of the area around the mouth of the Chicago River was quickly realized. To prevent the British and their Indian allies from recapturing this vital water transportation route, Fort Dearborn was built in 1803 on the south bank of the Chicago River. By the 1830s, urban settlers began arriving. In 1835, piers to protect the harbor entrance and a lighthouse to guide shipping were built. As Chicago grew into a city, which was incorporated in 1833, lakefront shipping expanded. 1848 saw the completion of the Illinois-Michigan Canal. In 1860, the Illinois and Michigan Canal was dredged, and in 1889, the Metropolitan Sanitary District of Greater Chicago was formed to begin building the Sanitary and Ship Canal. In 1900, the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal was completed; as a result, transportation and waste-carrying capacity was greatly increased and the river's flow was reversed inland to the Calumet River. In a span of 75 years, Chicago, specifically along Lake Michigan, became the center of intense commercial, industrial, and transportation development. Some major historical events that helped to guide the lakefront to what it is today are highlighted. An 1836 surveyor’s map by the Commissioners of the Illinois and Michigan Canal Company indicated that the area between Madison Street and 11 th Place from Michigan Avenue to the Lake be “open ground – no building”. -

Daughters of Charity Recall the 1871 Chicago Fire: 'It Traveled Like Lightning.'

Vincentian Heritage Journal Volume 34 Issue 1 Article 3 Summer 9-11-2017 Daughters of Charity Recall the 1871 Chicago Fire: 'It traveled like lightning.' Betty Ann McNeil D.C. DePaul University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj Recommended Citation McNeil D.C., Betty Ann (2017) "Daughters of Charity Recall the 1871 Chicago Fire: 'It traveled like lightning.'," Vincentian Heritage Journal: Vol. 34 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/vhj/vol34/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Vincentian Journals and Publications at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vincentian Heritage Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Daughters of Charity Recall the 1871 Chicago Fire: “It traveled like lightning.”1 BETTY ANN MCNEIL, D.C. 1 St. Joseph’s Hospital, Chicago — 1869-1872 and The Chicago Fire, Mission History, Chicago, St. Joseph’s Hospital 11-2-2-36(7), Daughters of Charity Archives Province of St. Louise, Emmitsburg, MD [APSL], formerly Archives Mater Dei Provincial House, Evansville, IN [AMDPH], p. 12. Hereinafter cited as Chicago Fire. Q Q Q Q QQ Q QQ QQ Q QQ QQ Q QQ Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q previous Q next Q BACK TO CONTENTS Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q article Q article Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Q Introduction he first Daughters of Charity arrived at Chicago in 1861.