Representation of Ethnic Minorities in Malayalam Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14

Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14 Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14 1 / 3 2 / 3 Chithram Vichithram play-icon. Chithram Vichithram. 01:40 - 02:00 | IST · Munshi play- ... Popular Movies. Bigil · Pizhai · Mamangam (Tamil) .... 09-Feb-2016 - you can watch malayalam full length comedy movies. See more ... Watch Bombay Movie Online With English Subtitles. A Hindu man and ... Chithram 1988 Malayalam Movie for Free Free Full Episodes, Malayalam Cinema, .... Showing results for "chitram malayalam movie subtitles" across Quikr ... Audition Audition Audition for a Kannada Serial and movie.. Malayalam cinema is the Indian film industry based in the southern state of Kerala, dedicated to ... Classical Carnatic music was heavily used in films like Chithram (1988), His Highness Abdullah (1990), ... film to release with subtitles (English) in outside Kerala, in other than film festival screenings. ... Retrieved 14 April 2011.. Thenmavin Kombath Full Movie - HD (English Subtitles) | Mohanlal ... the branch of Sweet Mango Tree) is a .... Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14 >> http://urllio.com/sgq44 a4c8ef0b3e The Association of Malayalam Movie Artists (AMMA) is an .... Chithram Vichithram play- icon. Chithram Vichithram. 01:40 - 02:00 | IST · Munshi play- ... Popular Movies. Bigil · Pizhai · Mamangam (Tamil) .... Distributed by, Varahi Chalana Chitram. Release date. 4 August 2016 (2016-08-04) (Premiere); 5 August 2016 (2016-08-05) (Worldwide). Running time. 136 minutes. Country, India. Language, Telugu. Manamantha (English: All of Us) is a 2016 Indian Telugu drama film written and directed by ... The film was partially reshot in Malayalam as Vismayam (English: ... Here is the list of best malayalam movies of all time. The list includes ... Bharatham 14. -

Postcolonial Pirate Domain." Postcolonial Piracy: Media Distribution and Cultural Production in the Global South

Poduval, Satish. "Hacking and Difference: Reflections on Authorship in the Postcolonial Pirate Domain." Postcolonial Piracy: Media Distribution and Cultural Production in the Global South. Ed. Lars Eckstein and Anja Schwarz. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014. 273–292. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 2 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781472519450.ch-012>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 2 October 2021, 06:23 UTC. Copyright © Lars Eckstein and Anja Schwarz 2014. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 12 Hacking and Difference Reflections on Authorship in the Postcolonial Pirate Domain Satish Poduval Philip K. Dick famously observed about science fiction that ‘Jules Verne’s story of travel to the moon is not SF because they go by rocket but because of where they go. It would be as much SF if they went by rubber band’ (Dick 1995: 57). A remark like that is peculiarly resonant in postcolonial spaces where historical experience tends to be framed as a story of travel, as a destinal narrative1 in which modernity is simul- taneously a destination to be reached and the ensemble of mechanisms destined to accelerate the journey. However, in recent decades, the helical loop of this narrative appears to be unravelling. Neither the vision nor the vehicle of modernization is any longer monopolized by the state or the older national elites, and earlier conceptions of a shared Third World identity forged by imperial exploitation and industrial backwardness do not typify the global South uniformly today. -

Malayalam Film Kilukkam Mp3 Songs Download

Malayalam film kilukkam mp3 songs download click here to download Movie: Kilukkam (K). Release: Category: Malayalam. Director: Priyadarshan. Music: SP Venkatesh. Stars: Mohanlal Innocent Jagathy Sreekumar. Download Kilukkam Malayalam Album Mp3 Songs By Various Here In Full Length. Tags: Kilukkam Malayalam movie Mp3 Songs Free download, Download Kilukkam film Movie Songs, kbps Hq High quality Mp3 Songs, free MP3. Kuttyweb Songs Kuttyweb Ringtones www.doorway.ru Free Mp3 Songs Download Video songs Download Kuttyweb Malayalam Songs Kuttywap Tamil Songs. Kilukkam Mp3 Songs - Mohanlal Hits , Kilukkam Songs Kilukkam Download Kilukkam Film Songs Kilukkam kbps Kilukkam kbps Tamil Songs | Hindi Songs | Malayalam Songs | Telugu Songs | Kannada Songs | English Songs Meena www.doorway.ru Kilukkam Songs Download- Listen Malayalam Kilukkam MP3 songs online free. Play Kilukkam Malayalam movie songs MP3 by S.p. Venkitesh and download. Meenavenalil Kilukkam Song mp3 Download. Meenavenalil Malayalam Film Song Kilukkam mp3. Meena Venalil Full Song | Malayalam Movie "kilukkam". Download Evergreen and New Malayalam Movie Songs @ ONMUSIQ. Kilukkam Full Malayalam mp3 songs,Kilukkam mp3 songs, HQ Mp3 songS, Kilukkam. Neela Venalil, Kilukkam. Download Malayalam song Neela Venalil from Movie Kilukkam! Link As" option. All songs are in mp3 format and bitrate of kbps. Kilukkampetti () Movie Mp3 Songs Added On , This Songs Added Only For Promotional Purposes. Kilukkampetti () Movie Mp3 Songs. 1. Songs Free Download,Mazhathullikilukkam () Mp3 Songs,Mazhathullikilukkam Malayalam Movie Mp3 Songs Free Download,Mazhathullikilukkam. Download Kilukkam Kilukilukkam Various Kilukkam Klukilukkam Mp3 Song Detail: Various is a famous Malayalam Singer and Popular for his Recent Album Malayalam Full Movie Kilukkam Kilukilukkam Ft Mohanlal Jagathy Sreekumar. Mazhathulli kilukkam malayalam movie mp3 songs free download movie name mazhathullikilukkam year Banner sarada pictures cast dileepnbsp. -

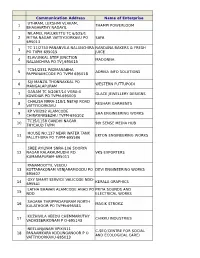

Communication Address Name of Enterprise 1 THAMPI

Communication Address Name of Enterprise UTHRAM, LEKSHMI VLAKAM, 1 THAMPI POWERLOOM BHAGAVATHY NADAYIL NILAMEL NALUKETTU TC 6/525/1 2 MITRA NAGAR VATTIYOORKAVU PO SAFA 695013 TC 11/2750 PANANVILA NALANCHIRA NANDANA BAKERS & FRESH 3 PO TVPM 695015 JUICE ELAVUNKAL STEP JUNCTION 4 MADONNA NALANCHIRA PO TV[,695015 TC54/2331 PADMANABHA 5 ADRIKA INFO SOLUTIONS PAPPANAMCODE PO TVPM 695018 SIJI MANZIL THONNAKKAL PO 6 WESTERN PUTTUPODI MANGALAPURAM GANAM TC 5/2067/14 VGRA-4 7 GLACE JEWELLERY DESIGNS KOWDIAR PO TVPM-695003 CHALISA NRRA-118/1 NETAJI ROAD 8 RESHAM GARMENTS VATTIYOORKAVU KP VIII/292 ALAMCODE 9 SHA ENGINEERING WORKS CHIRAYINKEEZHU TVPM-695102 TC15/1158 GANDHI NAGAR 10 9th SENSE MEDIA HUB THYCAUD TVPM HOUSE NO.137 NEAR WATER TANK 11 EKTON ENGINEERING WORKS PALLITHURA PO TVPM-695586 SREE AYILYAM SNRA-106 SOORYA 12 NAGAR KALAKAUMUDHI RD. VKS EXPORTERS KUMARAPURAM-695011 PANAMOOTTIL VEEDU 13 KOTTARAKONAM VENJARAMOODU PO DEVI ENGINEERING WORKS 695607 OXY SMART SERVICE VALICODE NDD- 14 KERALA GRAPHICS 695541 LATHA BHAVAN ALAMCODE ANAD PO PRIYA SOUNDS AND 15 NDD ELECTRICAL WORKS SAGARA THRIPPADAPURAM NORTH 16 MAGIK STROKZ KULATHOOR PO TVPM-695583 KUZHIVILA VEEDU CHEMMARUTHY 17 CHIKKU INDUSTRIES VADASSERIKONAM P O-695143 NEELANJANAM VPIX/511 C-SEC(CENTRE FOR SOCIAL 18 PANAAMKARA KODUNGANOOR P O AND ECOLOGICAL CARE) VATTIYOORKAVU-695013 ZENITH COTTAGE CHATHANPARA GURUPRASADAM READYMADE 19 THOTTAKKADU PO PIN695605 GARMENTS KARTHIKA VP 9/669 20 KODUNGANOORPO KULASEKHARAM GEETHAM 695013 SHAMLA MANZIL ARUKIL, 21 KUNNUMPURAM KUTTICHAL PO- N A R FLOUR MILLS 695574 RENVIL APARTMENTS TC1/1517 22 NAVARANGAM LANE MEDICAL VIJU ENTERPRISE COLLEGE PO NIKUNJAM, KRA-94,KEDARAM CORGENTZ INFOTECH PRIVATE 23 NAGAR,PATTOM PO, TRIVANDRUM LIMITED KALLUVELIL HOUSE KANDAMTHITTA 24 AMALA AYURVEDIC PHARMA PANTHA PO TVM PUTHEN PURACKAL KP IV/450-C 25 NEAR AL-UTHMAN SCHOOL AARC METAL AND WOOD MENAMKULAM TVPM KINAVU HOUSE TC 18/913 (4) 26 KALYANI DRESS WORLD ARAMADA PO TVPM THAZHE VILAYIL VEEDU OPP. -

IROWA DIRECTORY 2018 Indian Oil Retired Officers Welfare Association

IROWA DIRECTORY 2018 Indian Oil Retired Officers Welfare Association The Future of Energy? The Choice is Natural! Natural Gas is emerging as the fuel of the 21 century, steadily replacing liquid fuels and coal due to its low ecological footprint and inherent advantages for all user segments; Industries-Transport- Households. Indian Oil Corporation Limited (IndianOil), India's downstream petroleum major, proactively took up marketing of natural gas over a decade ago through its joint venture, Petronet LNG Ltd., that has set up two LNG (Liquefied Natural Gas) import terminals at Dahej and Kochi on the west coast of India. Over the years, the Corporation has rapidly expanded its customer base of gas-users by leveraging its proven marketing expertise in liquid fuels and its countrywide reach. Its innovative 'LNG at the Doorstep' initiative is highly popular with bulk consumers located away from pipelines. IndianOil is now importing more quantities of LNG directly to meet the increasing domestic demand. A 5-MMTPA LNG terminal being set up by IndianOil at Kamarajar Port in Ennore has achieved an overall progress of over 90% till now and would be commissioned by the end of 2018. The Corporation is currently operating city gas distribution (CGD) networks, offering compressed natural gas (CNG) for vehicles and piped natural gas (PNG) for households, in nine Geographical Areas (GA) through two joint ventures. Considering the growth potential in gas business, the Company is aggressively taking part in the various bidding rounds for Gas. IndianOil is also adding CNG as green auto-fuel at its 27,000+ fuel stations across India and is also collaborating with fleet owners and automobile manufacturers to promote the use of LNG as transportation fuel. -

28272676, [email protected] 28276652

1 Website: mca.gov.in Telephone No: 28276685, Email: 28272676, [email protected] 28276652 Fax: 28280436 1-117ff -Ncr)k GOVERNMENT OF INDIA cwq 4-1:lleio MINISTRY OF CORPORATE AFFAIRS comidq, & itcrcp, OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR OF COMPANIES, TAMILNADU, ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS, II Trf'--a-, 26, — 600 006. "SHASTRI BHAVAN", II FLOOR, 26, HADDOWS ROAD, CHENNAI - 600 006. ROC/CHN/S.20/8/PVT.PUB.ACT.DOR/STK-5 Dated: 10-07-2017 Form No. STK 5 Notice by Registrar for removal of name of a company from the register of companies [Pursuant to sub-section (1) of section 248 of the Companies Act, 2013 and rule 3 of the Companies (Removal of Names of Companies from the Register of Companies) Rules, 2016] Reference: In the matter of striking off of companies under section 248 (1) of the Companies Act, 2013, in respect of the following companies in table "A." Notice is hereby given that the Registrar of Companies has a reasonable cause to believe that — (1) The following companies in table" A " (List of 8822 Nos. of Companies) have not been carrying on any business or operation for a period of two immediately preceding financial years and have not made any application within such period for obtaining the status of dormant company under section 455. And, therefore, proposes to remove/strike off the names of the above mentioned companies from the register of companies and dissolve them unless a cause is shown to the contrary, within thirty days from the date of this notice. (2) Any person objecting to the proposed removal/striking off of name of the companies from the register of companies may send his/her objection to the office address mentioned here above within thirty days from the date of publication of this notice. -

Library – Books

MALAPPURAM D I E T LIBRARY PO BP ANGADI, TIRUR Accession Register Sl No Accessi Title Author Subject Call No Publish Price Used Date of Bill No Lendin Rack on No er Fund Purchas g Mode e 1 0.003 Bhasha Board of Linguisti 410.'494 Kerala 0.00 5 Dec Lending 10/A Sasthra Editors cs (in BOA/B Bhaasha 2013 Darppana Malayala Institute n m) 2 0.02 Cherusser Cherusser Religion 200. National 12.50 4 Dec Lending 4/C y ry CHE/C Books 2013 Bharatha Stall m 3 0.03 Sree Ramanuj Religion 200. Kerala 38 4 Dec Lending 4/C Maha an RAM/S Sahitya 2013 Bhagavat Ezhuthac Akademi ham han, Thunchat hu 4 0.06 Mahabha Ramanuj Religion 200. National 30 4 Dec Lending 4/C ratham an RAM/M Books 2013 (Kilippatt Ezhuthac Stall u). han, Thunchat hu 5 0.1 OUR Sealey, Knowled 001. Macmilla 0.00 25 Nov Referenc 1/A WORLD Leonard ge SEA/O n & Co 2013 e ENCYCL Ltd OPEDIA (vOL.10) 6 0.11 MACMI Board of Knowled 001. Macmilla 0 25 Nov Referenc 1/B LLAN Editors ge BOA/M n London 2013 e ENCYCL Ltd. OPEDIA 7 0.112 Kochu Sukumar Malayala 894.812 8 Bala 0.75 16 Dec Lending 19/C Thoppica an, m 03 Sahithya 2013 ry, Tatapura Childrens SUK/K Sahakara m Literature na Sangham Ltd. 8 0.12 JUNIOR Kenneth Knowled 001. Hamlyn 0 25 Nov Referenc 1/b ENCYCL Bailey ge KEN/J 2013 e OPEDIA 9 0.122 Charithra Narayana Educatio 372.0' Kerala 75 22 Dec Lending 9/D bodhana n, KV n: 909 894 Bhaasha 2013 m (C/2) Teaching NAR/C Institute > History (in Malayala m) 10 0.135 Inguninn Kuttikris Malayala 894.812 4 Current 3.50 14 Dec Lending 18/A angolam hnamarar m Essay KUT/I Books 2013 11 0.1458 Mother Gorky, English 823. -

Mohanlal Filmography

Mohanlal filmography Mohanlal Viswanathan Nair (born May 21, 1960) is a four-time National Award-winning Indian actor, producer, singer and story writer who mainly works in Malayalam films, a part of Indian cinema. The following is a list of films in which he has played a role. 1970s [edit]1978 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes [1] 1 Thiranottam Sasi Kumar Ashok Kumar Kuttappan Released in one center. 2 Rantu Janmam Nagavally R. S. Kurup [edit]1980s [edit]1980 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Manjil Virinja Pookkal Poornima Jayaram Fazil Narendran Mohanlal portrays the antagonist [edit]1981 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Sanchari Prem Nazir, Jayan Boban Kunchacko Dr. Sekhar Antagonist 2 Thakilu Kottampuram Prem Nazir, Sukumaran Balu Kiriyath (Mohanlal) 3 Dhanya Jayan, Kunchacko Boban Fazil Mohanlal 4 Attimari Sukumaran Sasi Kumar Shan 5 Thenum Vayambum Prem Nazir Ashok Kumar Varma 6 Ahimsa Ratheesh, Mammootty I V Sasi Mohan [edit]1982 No Film Co-stars Director Role Other notes 1 Madrasile Mon Ravikumar Radhakrishnan Mohan Lal 2 Football Radhakrishnan (Guest Role) 3 Jambulingam Prem Nazir Sasikumar (as Mohanlal) 4 Kelkkatha Shabdam Balachandra Menon Balachandra Menon Babu 5 Padayottam Mammootty, Prem Nazir Jijo Kannan 6 Enikkum Oru Divasam Adoor Bhasi Sreekumaran Thambi (as Mohanlal) 7 Pooviriyum Pulari Mammootty, Shankar G.Premkumar (as Mohanlal) 8 Aakrosham Prem Nazir A. B. Raj Mohanachandran 9 Sree Ayyappanum Vavarum Prem Nazir Suresh Mohanlal 10 Enthino Pookkunna Pookkal Mammootty, Ratheesh Gopinath Babu Surendran 11 Sindoora Sandhyakku Mounam Ratheesh, Laxmi I V Sasi Kishor 12 Ente Mohangal Poovaninju Shankar, Menaka Bhadran Vinu 13 Njanonnu Parayatte K. -

A Glottochronological Insight Into Malayalam and Telugu

International Journal of Innovations in TESOL and Applied Linguistics IJITAL ISSN: 2454-6887 Vol. 6, Issue. 1; 2020 Frequency: Quarterly © 2020 Published by ASLA, AUH, India Impact Factor: 6.851 A Glottochronological Insight into Malayalam and Telugu P. Lakshmi Nair, Sirisha Yalamanchili, Sanjay K. Jha, Shradhanwita Singh Amity School of Liberal Arts Amity University Haryana, India Received: SEP. 15, 2020 Accepted: OCT. 23, 2020 Published: NOV. 30, 2020 Abstract The prime objective of this study is to explore the degree of similarities between Malayalam and Telugu words using glottochronological approach. In doing so a representative sample of 125 words of each part of speech i.e, Noun, Verb, Adjective and Adverb were taken and the total representative sample were 500 words from Malayalam followed by listing their equivalents in Telugu. The findings revealed 185 words with phonological similarity between Malayalam and Telugu. These 185 words are classified into 81 completely similar words and 104 partially similar words. These partially similar words were analysed phonologically. The phonological analysis shows that partially similar words are following assimilation, sandhi and dissimilation. 1. INTRODUCTION Malayalam and Telugu are from Dravidian family. The communicative words of Malayalam and Telugu share similarities not only in terms pronunciations but also in terms of sharing common root words deriving from Sanskrit. Unlike many languages of northern and western India, these languages are not easy to pronounce. Malayalam is a language spoken in Kerala, in India. It has its own script, distinct from other scripts used in India. Malayalam has as many as 6 different articulation points for consonants and also has retroflex consonants. -

Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14

Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14 Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14 1 / 3 2 / 3 Here is the list of best malayalam movies of all time. The list includes ... Bharatham 14. Bharatham (1991). 147 min | Musical, Drama. 8.4 ... Chitram (2000).. Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14. 1/3. Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14. 2/3. Kakkakuyil is a 2001 Malayalam comedy film .... Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14 >>> DOWNLOAD (Mirror #1). a363e5b4ee Two Countries (2015) English Subtitles Malayalam Movie .. Distributed by, Varahi Chalana Chitram. Release date. 4 August 2016 (2016-08-04) (Premiere); 5 August 2016 (2016-08-05) (Worldwide). Running time. 136 minutes. Country, India. Language, Telugu. Manamantha (English: All of Us) is a 2016 Indian Telugu drama film written and directed by ... The film was partially reshot in Malayalam as Vismayam (English: .... you can find some malayalam classics with subtitles on youtube itself. Here are my picks Sphadikam(crystal) (must see) - the trend setter in malayalam masala .... Malayalam Full Movie | Chithram HD Movie | Mohanlal, Nedumudi Venu, Sreenivasan. 2 Followers .... Thenmavin Kombath Full Movie - HD (English Subtitles) | Mohanlal ... the branch of Sweet Mango Tree) is a .... Drishyam Malayalam full movie with English subs | #Mohanlal | #Meena | Malayalam Superhit Movie .... Indrajalam 1990 Full Malayalam Movie | Mohanlal, Sreeja | Malayalam Full Length Movies 2016. Latest .... Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14 >> http://urllio.com/sgq44 a4c8ef0b3e The Association of Malayalam Movie Artists (AMMA) is an .... Amazon.com: Aaryan Malayalam DVD With English Subtitles: Mohanlal: Movies & TV.. 09-Feb-2016 - you can watch malayalam full length comedy movies. See more ... Watch Bombay Movie Online With English Subtitles. -

Library Details the Library Has Separate Reference Section/ Journals Section and Reading Room : Yes

ST. JOHN THE BAPTIST’S COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, NEDUMKUNNAM Library Details The Library has separate reference section/ Journals section and reading room : Yes Number of books in the library : 8681 Total number of educational Journals/ periodicals being subscribed : 23 Number of encyclopaedias available in the library : 170 Number of books available in the reference section of the library : 1077 Seating capacity of the reading room of the library : 75 Books added in Last quarter Number of books in the library : 73 Total number of educational Journals/ periodicals being subscribed : 1 Number of books available in the reference section of the library : 9 Library Stock Register ACC_NO BOOK_NAME AUTHOR 1 Freedom At Midnight Collins, Larry & Lapierre, Dominique 2 Culture And Civilisation Of Ancient India In Historical Outline Kosambi,D.D. 3 Teaching Of History: A Practical Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 4 Teaching Of History:a Practical Approach Aggarwal,j.c. 5 School Inspection Ststem:a Modern Approach Singhal, R. P. 6 Teaching Of Social Studies : A Practical Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 7 Teaching Of Social Studies: A Practical Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 8 School Inspection System: A Modern Approach Aggarwal, J. C. 9 Fundamentals Of Classroom Teaching Taiwa, Adedison A. 10 Introduction To Statistical Methods Gupta, C. B. & Gupta, Vijay 11 Textbook Of Botany Vol.2 Pandey, S. N. & Others 12 Textbook Of Botany. Vol 1 Pandey, S. N. & Trivedi, P. S. 13 Textbook Of Botany. Vol.3 Pandey, S. N. & Chadha A. 14 Principles Of Education Venkateswaran, S. 15 National Policy On Education: An Overview Ram, Atma & Sharma, K. D. -

Postcolonial Piracy THEORY for GLOBAL AGE

EDE ITITEDD BY LARS ECKSTEIN AND ANJA SCHWARZ MMEEDDIA DIDISTSTRIRIBUBUTITIONON ANDND CUCULTLTURURAALL PRORODUDUCTCTIIOON IINN TTHHE GLGLOBOBALAL SOUO THTH Postcolonial Piracy THEORY FOR GLOBAL AGE Series Editors: Gurminder K. Bhambra and Robin Cohen Editorial Board: Michael Burawoy (University of California Berkeley, USA), Neera Chandoke, (University of Delhi, India) Robin Cohen (University of Oxford, UK), Peo Hansen (Linköping University, Sweden) John Holmwood (University of Nottingham, UK), Walter Mignolo (Duke University, USA), Emma Porio (Ateneo de Manila University, Philippines), Boaventura de Sousa Santos (University of Coimbra, Portugal). Globalization is widely viewed as the current condition of the world, only recently come into being. There is little engagement with its long histories and how these histories continue to have an impact on current social, political, and economic configurations and understandings. Theory for a Global Age takes ‘the global’ as the already-always existing condition of the world and one that should have informed analysis in the past as well as informing analysis for the present and future. The series is not about globalization as such, but, rather, it addresses the impact a properly critical reflection on ‘the global’ might have on disciplines and different fields within the social sciences and humanities. It asks how we might understand our present and future differently if we start from a critical examination of the idea of the global as a political and interpretive device; and what consequences this would have for reconstructing our understandings of the past, including our disciplinary pasts. Each book in the series focuses on a particular theoretical issue or topic of empirical controversy and debate, addressing theory in a more comprehensive and interconnected manner in the process.