M C P H F I L M C L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Draft PROGRAMME October 16

“Media and Entertainment Business Conclave” Draft PROGRAMME October 16 -17, 2012 As on October 8th, 2012 Time Theme Day – I : 16 October 2012 9am – 10am Registration 10 -11 am Inaugural Lighting of Lamp Welcome Address : Dr. Kamal Haasan, Chairman, Media & Entertainment Business Conclave, FICCI Release of FICCI –Deloitte Knowledge Report Keynote Address : Barrie Osborne, Oscar-winning Director-Producer, Hollywood Inaugural Address: Shri Uday K Varma, Secretary, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting, Government of India Vote of Thanks: P. Murari, Advisor to President, FICCI 1 Session chaired by Kamal Haasan, Chairman, FICCI MEBC 11:15 – MEBC Broadcast Industry Knowledge Series: Opportunities in the digitized era. 12:30 pm Policy-makers and industry stakeholders share their vision and knowledge on the scope and opportunities for the sector during the progress of digitization. N Parameshwaran, Principal Advisor, TRAI* K Madhavan, MD, Asianet Rahul Johri , Senior Vice President & General Manager- South Asia, Discovery Networks Asia-Pacific Narayan Rao, Executive Vice Chairman, NDTV Group Supriya Sahu, Joint Secretary, Ministry of Information & Broadcasting * Ashok Mansukhani, President, MSO Alliance Moderated by : Bhupendra Chaubey, National Bureau Chief, CNN IBN* 11:15 – Redefining Digital Production 12:30 pm The concept of what's 'eye candy' in feature films has evolved over time - films are about people, feelings, ideas, circumstances and relationships and the 'emotional quotient' is provided essentially by an able director through screenplay, actors, music, cinematography. However, one element has changed every aspect of this mix and that is "visual effects" which is now a source of inspiration from the "pre- production" stage itself. This session will look at making cutting-edge visual effects come alive with an energizing dialogue with experts from Hollywood and India. -

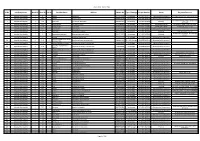

Accused Persons Arrested in Kollam Rural District from 07.06.2020To13.06.2020

Accused Persons arrested in Kollam Rural district from 07.06.2020to13.06.2020 Name of Name of Name of the Place at Date & Arresting the Court Sl. Name of the Age & Cr. No & Police father of Address of Accused which Time of Officer, at which No. Accused Sex Sec of Law Station Accused Arrested Arrest Rank & accused Designation produced 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 1953/2020 U/s 269 IPC & 118(e) of GEETHA KP Act & VILASOM, 13-06-2020 ANCHAL G.PUSHPAK 20, RO JN Sec. 5 of BAILED BY 1 ABHIJITH SURESH KURUVIKKONAM, at 21:05 (Kollam UMAR ,SI OF Male ANCHAL Kerala POLICE ANCHAL Hrs Rural) POLICE Epidemic VILLAGE Diseases Ordinance 2020 1952/2020 U/s 188, 269 KOCHU VEEDU, IPC & Sec. 5 13-06-2020 ANCHAL G.PUSHPAK MADHAVA 33, NEAR ANCHAL RO JN of Kerala BAILED BY 2 ANOOP at 20:15 (Kollam UMAR ,SI OF N NAIR Male CHC, ANCHAL ANCHAL Epidemic POLICE Hrs Rural) POLICE VILLAGE Diseases Ordinance 2020 1952/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC & Sec. 5 KAILASOM, 13-06-2020 ANCHAL G.PUSHPAK AJAYA 25, RO JN of Kerala BAILED BY 3 ANANDU ANCHAL at 20:15 (Kollam UMAR ,SI OF KUMAR Male ANCHAL Epidemic POLICE VILLAGE Hrs Rural) POLICE Diseases Ordinance 2020 1951/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC & Sec. 5 THIRUVATHIRA 13-06-2020 ANCHAL G.PUSHPAK 25, RO JN of Kerala BAILED BY 4 AROMAL SASIDARAN VAKKAMMUK at 20:25 (Kollam UMAR ,SI OF Male ANCHAL Epidemic POLICE THAZHAMEL Hrs Rural) POLICE Diseases Ordinance 2020 1951/2020 U/s 188, 269 IPC & Sec. -

Analysis of Trauma Theory in Goat Days and Khadamma SURYA S.KUMAR1, SONIA CHELLERIAN2 1Student,M.Phil

Annals of R.S.C.B., ISSN:1583-6258, Vol. 25, Issue 6, 2021, Pages. 8951 - 8954 Received 25 April 2021; Accepted 08 May 2021. Expectation to Despair: Analysis of Trauma Theory in Goat Days and Khadamma SURYA S.KUMAR1, SONIA CHELLERIAN2 1Student,M.Phil. English,Department of English Language and LiteratureAmrita School of Arts and Sciences,KochiAmrita Vishwavidyapeetham, [email protected] 2Asst.Professor,Department of English LiteratureAmrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi [email protected] Abstract Literature influences human beings in different ways and also helps to give new perspectives regarding each and every matter. The language of literature has a power to get the attention of the readers. It has a room for memories, flashbacks and moments which are filled with discomfort, injury as well as trauma.Works like Khadammaand Goat days throw light into the inner skirts of the experiences that the characters go through and offer wide platform for the analysis of their mindscape. Traumacan be considered as an individual‟ssensitivereaction to a particularoccasion that annoysformernotions of aperson‟s sense of life. The central feature of trauma novel is the change of the self-ignited due to anexteriorfrightening occurrence.Ashwathy of Khadammaand Najeeb of Goat days are victims of trauma that dissect their identity. They experience a sense of disillusionment and loss of identity which leads them to a traumatic situation. Both the characters reached gulf in the hope of earning money but their journey of hope soon turned to despair with the cruel treatment of their sponsors. Their misery forced them into trauma where they questiontheir own identity. -

Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions Poster Sessions Continuing

Sessions and Events Day Thursday, January 21 (Sessions 1001 - 1025, 1467) Friday, January 22 (Sessions 1026 - 1049) Monday, January 25 (Sessions 1050 - 1061, 1063 - 1141) Wednesday, January 27 (Sessions 1062, 1171, 1255 - 1339) Tuesday, January 26 (Sessions 1142 - 1170, 1172 - 1254) Thursday, January 28 (Sessions 1340 - 1419) Friday, January 29 (Sessions 1420 - 1466) Spotlight and Hot Topic Sessions More than 50 sessions and workshops will focus on the spotlight theme for the 2019 Annual Meeting: Transportation for a Smart, Sustainable, and Equitable Future . In addition, more than 170 sessions and workshops will look at one or more of the following hot topics identified by the TRB Executive Committee: Transformational Technologies: New technologies that have the potential to transform transportation as we know it. Resilience and Sustainability: How transportation agencies operate and manage systems that are economically stable, equitable to all users, and operated safely and securely during daily and disruptive events. Transportation and Public Health: Effects that transportation can have on public health by reducing transportation related casualties, providing easy access to healthcare services, mitigating environmental impacts, and reducing the transmission of communicable diseases. To find sessions on these topics, look for the Spotlight icon and the Hot Topic icon i n the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section beginning on page 37. Poster Sessions Convention Center, Lower Level, Hall A (new location this year) Poster Sessions provide an opportunity to interact with authors in a more personal setting than the conventional lecture. The papers presented in these sessions meet the same review criteria as lectern session presentations. For a complete list of poster sessions, see the “Sessions, Events, and Meetings” section, beginning on page 37. -

I. I. T. M. Research Reports

I. I. T. M. RESEARCH REPORTS • Energetic consistency of truncated models, Asnani G.C., August 1971, RR-001. • Note on the turbulent fluxes of heat and moisture in the boundary layer over the Arabian Sea, Sinha S., August 1971, RR-002. • Simulation of the spectral characteristics of the lower atmosphere by a simple electrical model and using it for prediction, Sinha S., September 1971, RR-003. • Study of potential evapo-transpiration over Andhra Pradesh, Rakhecha P.R., September 1971, RR-004. • Climatic cycles in India-1: Rainfall, Jagannathan P. and Parthasarathy B., November 1971, RR-005. • Tibetan anticyclone and tropical easterly jet, Raghavan K., September 1972, RR-006. • Theoretical study of mountain waves in Assam, De U.S., February 1973, RR-007. • Local fallout of radioactive debris from nuclear explosion in a monsoon atmosphere, Saha K.R. and Sinha S., December 1972, RR-008. • Mechanism for growth of tropical disturbances, Asnani G.C. and Keshavamurty R.N., April 1973, RR-009. • Note on “Applicability of quasi-geostrophic barotropic model in the tropics”, Asnani G.C., February 1973, RR-010. • On the behaviour of the 24-hour pressure tendency oscillations on the surface of the earth, Part-I: Frequency analysis, Part-II: Spectrum analysis for tropical stations, Misra B.M., December 1973, RR-011. • On the behaviour of the 24 hour pressure tendency oscillations on the surface of the earth, Part-III : Spectrum analysis for the extra-tropical stations, Misra B.M., July 1976, RR-011A. • Dynamical parameters derived from analytical functions representing Indian monsoon flow, Awade S.T. and Asnani G.C., November 1973, RR-012. -

Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks

Flood 2019 - Vythiri Taluk Sl No Localbody Name Ward No Door No Sub No Resident Name Address Mobile No Type of Damage Unique Number Status Rejection Remarks 1 Kalpetta Municipality 1 0 kamala neduelam 8157916492 No damage 31219021600235 Approved(Disbursement) RATION CARD DETAILS NOT AVAILABLE 2 Kalpetta Municipality 1 135 sabitha strange nivas 8086336019 No damage 31219021600240 Disbursed to Government 3 Kalpetta Municipality 1 138 manjusha sukrutham nedunilam 7902821756 No damage 31219021600076 Pending THE ADHAR CARD UPDATED ANOTHER ACCOUNT 4 Kalpetta Municipality 1 144 devi krishnan kottachira colony 9526684873 No damage 31219021600129 Verified(LRC Office) NO BRANCH NAME AND IFSC CODE 5 Kalpetta Municipality 1 149 janakiyamma kozhatatta 9495478641 >75% Damage 31219021600080 Verified(LRC Office) PASSBOOK IS NO CLEAR 6 Kalpetta Municipality 1 151 anandavalli kozhathatta 9656336368 No damage 31219021600061 Disbursed to Government 7 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 chandran nedunilam st colony 9747347814 No damage 31219021600190 Withheld PASSBOOK NOT CLEAR 8 Kalpetta Municipality 1 16 3 sangeetha pradeepan rajasree gives nedunelam 9656256950 No damage 31219021600090 Withheld No damage type details and damage photos 9 Kalpetta Municipality 1 161 shylaja sasneham nedunilam 9349625411 No damage 31219021600074 Disbursed to Government Manjusha padikkandi house 10 Kalpetta Municipality 1 172 3 maniyancode padikkandi house maniyancode 9656467963 16 - 29% Damage 31219021600072 Disbursed to Government 11 Kalpetta Municipality 1 175 vinod madakkunnu colony -

Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14

Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14 Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14 1 / 3 2 / 3 Chithram Vichithram play-icon. Chithram Vichithram. 01:40 - 02:00 | IST · Munshi play- ... Popular Movies. Bigil · Pizhai · Mamangam (Tamil) .... 09-Feb-2016 - you can watch malayalam full length comedy movies. See more ... Watch Bombay Movie Online With English Subtitles. A Hindu man and ... Chithram 1988 Malayalam Movie for Free Free Full Episodes, Malayalam Cinema, .... Showing results for "chitram malayalam movie subtitles" across Quikr ... Audition Audition Audition for a Kannada Serial and movie.. Malayalam cinema is the Indian film industry based in the southern state of Kerala, dedicated to ... Classical Carnatic music was heavily used in films like Chithram (1988), His Highness Abdullah (1990), ... film to release with subtitles (English) in outside Kerala, in other than film festival screenings. ... Retrieved 14 April 2011.. Thenmavin Kombath Full Movie - HD (English Subtitles) | Mohanlal ... the branch of Sweet Mango Tree) is a .... Chithram Malayalam Movie Subtitles 14 >> http://urllio.com/sgq44 a4c8ef0b3e The Association of Malayalam Movie Artists (AMMA) is an .... Chithram Vichithram play- icon. Chithram Vichithram. 01:40 - 02:00 | IST · Munshi play- ... Popular Movies. Bigil · Pizhai · Mamangam (Tamil) .... Distributed by, Varahi Chalana Chitram. Release date. 4 August 2016 (2016-08-04) (Premiere); 5 August 2016 (2016-08-05) (Worldwide). Running time. 136 minutes. Country, India. Language, Telugu. Manamantha (English: All of Us) is a 2016 Indian Telugu drama film written and directed by ... The film was partially reshot in Malayalam as Vismayam (English: ... Here is the list of best malayalam movies of all time. The list includes ... Bharatham 14. -

St. Albert's College (Autonomous) Provisional General Ranklist Ba Economics

ST. ALBERT'S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) PROVISIONAL GENERAL RANKLIST BA ECONOMICS No Rank ID Fullname Index 1 1 2100681 CELIA SEBASTIAN 1473.00219 2 2 210002335 SIVA P BABU 1461.00219 3 3 210007183 ANNA MEHRI 1459.00219 4 4 210005776 I.M.NANDAKUMAR 1458.00219 5 5 2100971 DEVAKI.P.S. 1456.00218 6 6 210004574 ASWATHY V S 1455.00218 7 6 210002830 NILA A 1455.00217 8 7 2100804 THERESA SABU 1454.00219 9 7 210008793 NANDHANA P S 1454.00217 10 8 210006629 AGNA VARGHESE 1453.00219 11 9 210005828 ZENUNNI K V 1452.00218 12 9 210001965 AMRUTHA AJAY CA 1452.00218 13 9 210003776 VYSHNAVI R 1452.00218 14 10 210007784 UTHARA ANILKUMAR 1451.00218 15 11 2100511 ANN GLORIA GOMEZ 1450.0022 16 11 210001089 AMBER NICOLE LOBO 1450.0022 17 11 210004886 MOHAMMED MITHILAJ C R 1450.0022 18 12 210001237 CHARLIN CLOUD 1449.00218 19 12 2100310 BHAVYA JOSEMON 1449.00217 20 13 210001779 ASHNA JOSEPH 1448.00218 21 13 210006502 DONA MARIA SOJI 1448.00217 22 13 210006044 NAVYA PRASANNAKUMAR 1448.00217 23 14 2100272 KALYANI PADMAN 1446.20108 24 15 2100438 ARUN G. RAO 1446.00219 25 15 210002428 TELMA THOMAS 1446.00216 26 16 2100120 RIFA FATHIMA A R 1445.00217 27 17 2100591 ASHMI REMYA T X 1444.00219 28 17 210004395 MUBASHIRA FIROS 1444.00218 29 17 210002104 TERESA JACKSON 1444.00218 ST. ALBERT'S COLLEGE (AUTONOMOUS) PROVISIONAL GENERAL RANKLIST BA ECONOMICS No Rank ID Fullname Index 30 17 210002909 ANAINA RAJU 1444.00217 31 18 210001221 AGNES MARIA XAVIER 1443.00219 32 18 210003393 JOSEPH THOMAS 1443.00216 33 19 210004435 SREENANDANA . -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

2018 Holds a Spectacular Lineup of Films from All Around the World in Store for You, and Two Special Performances

“IT MUST BE LOVE ON THE BRAIN” “IT MUST BE LOVE ON THE BRAIN” t the 9th edition of BQFF, hosted along with our beloved partners the Goethe-Institut/Max Mueller Bhavan (GI / MMB), we present a staggering A89 films from over 30 countries. Like every previous year, this year’s festival will be breathless, wild, fun, strange and intense. It will put you on social overdrive, because let’s face it: some of you come just to meet your friends. Watch out for our three specially curated packages. One set of films brought to us by GI / MMB, including our Saturday night Centrepiece, Ein Weg (Paths), comes from the prestigious Berlinale festival in Germany. Another package of LGBT shorts from the UK is brought to us by a British Council international touring programme in association with BFI Flare. For the second time in our history, BQFF is collaborating with the film curator and archivist Thomas Waugh, founder-director of the Queer Media Database Canada-Québec. He will introduce and screen a package called “I Confess”, autobiographical shorts from the Canadian Queer Film Archive. This year we have something über special to announce: in 2017 The Bangalore Queer Festival Trust was set up as an independent entity that will work solely for the festival in the years to come, starting with the 10th Anniversay splash in 2019! We hope you will all stay with as collaborators, supporters, film lovers, performers and just generally a marvellously ragtag bunch of travellers in the future! To give you a quick recap of last year’s festival, BQFF 2017 (24-26 February 2017) was held at Alliance Française de Bangalore and the Goethe-Institut /Max Mueller Bhavan. -

Malayalam Biopics: from Books to Films

MALAYALAM BIOPICS: FROM BOOKS TO FILMS Gayatri Binu Registered Number: 1324032 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Communication Christ University Bengaluru 2015 Program Authorized to Offer Degree Department of Media Studies II Authorship Christ University Declaration Department of Media Studies This is to certify that I have examined this copy of a master’s thesis by Gayatri Binu Registered Number: 1324032 and have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Committee Members: _____________________________________________________ _____________________________________________________ Date: __________________________________ III IV I, Gayatri Binu, confirm that this dissertation and the work presented in it are original. 1. Where I have consulted the published work of others this is always clearly attributed. 2. Where I have quoted from the work of others the source is always given. With the exception of such quotations this dissertation is entirely my own work. 3. I have acknowledged all main sources of help. 4. If my research follows on from previous work or is part of a larger collaborative research project I have made clear exactly what was done by others and what I have contributed myself. 5. I am aware and accept the penalties associated with plagiarism. Date: V VI Abstract Malayalam Biopics: From Books to Films Gayatri Binu MS in Communication, Christ University, Bangalore This article talks about the difficulties that emerge when considering biographical films that are focused around biographical or autobiographical works of writing utilizing careful investigations of three Malayalam films. -

Members of the Local Authorities Alappuzha District

Price. Rs. 150/- per copy UNIVERSITY OF KERALA Election to the Senate by the member of the Local Authorities- (Under Section 17-Elected Members (7) of the Kerala University Act 1974) Electoral Roll of the Members of the Local Authorities-Alappuzha District Name of Roll Local No. Authority Name of member Address 1 LEKHA.P-MEMBER SREERAGAM, KARUVATTA NORTH PALAPPRAMBILKIZHAKKETHIL,KARUVATTA 2 SUMA -ST. NORTH 3 MADHURI-MEMBER POONTHOTTATHIL,KARUVATTA NORTH 4 SURESH KALARIKKAL KALARIKKALKIZHAKKECHIRA, KARUVATTA 5 CHANDRAVATHY.J, VISHNUVIHAR, KARUVATTA 6 RADHAMMA . KALAPURAKKAL HOUSE,KARUVATTA 7 NANDAKUMAR.S KIZHAKKEKOYIPURATHU, KARUVATTA 8 SULOCHANA PUTHENKANDATHIL,KARUVATTA 9 MOHANAN PILLAI THUNDILVEEDU, KARUVATTA 10 Karuvatta C.SUJATHA MANNANTHERAYIL VEEDU,KARUVATTA 11 K.R.RAJAN PUTHENPARAMBIL,KARUVATTA Grama Panchayath Grama 12 AKHIL.B CHOORAKKATTU HOUSE,KARUVATTA 13 T.Ponnamma- ThaichiraBanglow,Karuvatta P.O, Alappuzha 14 SHEELARAJAN R.S BHAVANAM,KARUVATTA NORTH MOHANKUMAR(AYYAPP 15 AN) MONEESHBHAVANAM,KARUVATTA 16 Sosamma Louis Chullikkal, Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 17 Jayamohan Shyama Nivas, Pollethai.P.O 18 Kala Thamarappallyveli,Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 19 Dinakaran Udamssery,Pollethai. P.O, Alappuzha 20 Rema Devi Puthenmadam, Kalvoor. P.O, Alappuzha 21 Indira Thilakan Pandyalakkal, Kalavoor. P.O, Alappuzha 22 V. Sethunath Kunnathu, Kalavoor. P.O, Alappuzha 23 Reshmi Raju Rajammalayam, Pathirappally, Alappuzha 24 Muthulekshmi Castle, Pathirappaly.P.O, Alappuzha 25 Thresyamma( Marykutty) Chavadiyil, Pathirappally, Alappuzha 26 Philomina (Suja) Vadakkan parambil, Pathirappally, Alappuzha Grama Panchayath Grama 27 South Mararikulam Omana Moonnukandathil, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 28 Alice Sandhyav Vavakkad, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 29 Laiju. M Madathe veliyil , Pathirappally P O 30 Sisily (Kunjumol Shaji) Puthenpurakkal, Pathirappally. P.O, Alappuzha 31 K.A.