Homenaje a Profesor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998) Fryderyk Kwiatkowski Jagiellonian University in Kraków, [email protected]

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Nebraska, Omaha Journal of Religion & Film Volume 21 Article 34 Issue 1 April 2017 4-1-2017 How To Attain Liberation From a False World? The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998) Fryderyk Kwiatkowski Jagiellonian University in Kraków, [email protected] Recommended Citation Kwiatkowski, Fryderyk (2017) "How To Attain Liberation From a False World? The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998)," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 34. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol21/iss1/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How To Attain Liberation From a False World? The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998) Abstract In the second half of the 20th century, a fascinating revival of ancient Gnostic ideas in American popular culture could be observed. One of the major streams through which Gnostic ideas are transmitted is Hollywood cinema. Many works that emerged at the end of 1990s can be viewed through the ideas of ancient Gnostic systems: The Truman Show (1998), The Thirteenth Floor (1999), The Others (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001) or The Matrix trilogy (1999-2003). In this article, the author analyses Dark City (1998) and demonstrates that the story depicted in the film is heavily indebted to the Gnostic myth of Sophia. -

Acts 13 Highligted C

Acts 13 Game On—Taking The Gospel to the World May 26-27, 2018 Mark Foreman NCCC v Taking the Risk—Paul and Barnabas Are Sent (1-5) Ø A church that is birthed as a mission becomes missional. It’s in the DNA. Ø The Antioch church gave the world their best—Paul and Barnabas. • Luke tells us only Paul’s story, none of the other Apostles, for example Thomas traveled from Syria to India. Ø They fasted and prayed and were sent out. Ø The laying on of hands is more than symbolic. It is asking for the Spirit’s power and guidance for the trip. Ø They traveled 15 miles to the coast with their helper, John Mark (Barnabas cousin & who’s mom hosted the prayer meeting in Jerusalem). Ø They sailed first for Barnabas’ home island—Cyprus. They began as they almost always did with the ready-made audience in the synagogue. v Success and Resistance Among Gentiles on the Island of Cyprus (6-12) Ø Luke doesn’t record every preaching event but gives us the East and West Coast summary. • Perhaps they started on Cyprus because it was Barnabas’ home. • A week’s travel would bring them to Paphos the capital, 90 miles. Ø They first meet Bar-Jesus (Elymas), the Jewish sorcerer. • Perhaps they first spoke in the Synagogue or met in the marketplace. • It is likely he gave “spiritual” advise to the proconsul. Ø The intelligent proconsul (governor), Sergius Paulus, sent for them. Ø Elymas, realized he’s was losing control and perhaps his employment opposed Paul and Barnabas. -

A Defense of Basilides the False

A Defense of Basilides the False In about 1905, I knew that the omniscient pages (A to All) of the firstvolume of Montaner and Simon's Hispano-American Encyclopedic Dictionary con tained a small and alarming drawing of a sort of king, with the profiled head of a rooster, a virile torso with open arms brandishing a shield and a whip, and the rest merely a coiled tail, which served as a throne. In about 1916, I read an obscure passage in Quevedo: "There was the accursed Basilides the heresiarch. There was Nicholas of Antioch, Carpocrates and Cerinthus and the infamous Ebion. Later came Va lentin us, he who believed sea and silence to be the beginning of everything." In about 1923, in Geneva, I came across some heresiological book in German, and I realized that the fateful drawing represented a certain miscellaneous god that was horribly worshiped by the very same Basilides. I also learned what desperate and admirable men the Gnostics were, and I began to study their passionate speculations. Later I was able to investigate the scholarly books of Mead (in the German version: Fragmente eines verschollenen Glaubens, 1902) and Wo lfgang Schultz (Dokumente der Gnosis, 1910), and the articles by Wilhelm Bousset in the Encyclopedia Britannica. To day I would like to summarize and illustrate one of their cosmogonies: precisely that of Basilides the here siarch. I follow entirely the account given by Irenaeus. I realize that many doubt its accuracy, but I suspect that this disorganized revision of musty dreams may in itself be a dream that never inhabited any dreamer. -

The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998) Fryderyk Kwiatkowski Jagiellonian University in Kraków, [email protected]

Journal of Religion & Film Volume 21 Article 34 Issue 1 April 2017 4-1-2017 How To Attain Liberation From a False World? The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998) Fryderyk Kwiatkowski Jagiellonian University in Kraków, [email protected] Recommended Citation Kwiatkowski, Fryderyk (2017) "How To Attain Liberation From a False World? The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998)," Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 21 : Iss. 1 , Article 34. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol21/iss1/34 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Religion & Film by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. How To Attain Liberation From a False World? The Gnostic Myth of Sophia in Dark City (1998) Abstract In the second half of the 20th century, a fascinating revival of ancient Gnostic ideas in American popular culture could be observed. One of the major streams through which Gnostic ideas are transmitted is Hollywood cinema. Many works that emerged at the end of 1990s can be viewed through the ideas of ancient Gnostic systems: The Truman Show (1998), The Thirteenth Floor (1999), The Others (2001), Vanilla Sky (2001) or The Matrix trilogy (1999-2003). In this article, the author analyses Dark City (1998) and demonstrates that the story depicted in the film is heavily indebted to the Gnostic myth of Sophia. He bases his inquiry on the newest research results in Gnostic Studies in order to highlight the importance of definitional problems within the field and how carefully the concept of “Gnosticism” should be applied to popular culture studies. -

The Gospel of Thomas and Plato

The Gospel of Thomas and Plato Ivan Miroshnikov - 978-90-04-36729-6 Downloaded from Brill.com02/10/2020 03:36:56PM via University of Helsinki Nag Hammadi and Manichaean Studies Editors Johannes van Oort Einar Thomassen Editorial Board J.D. Beduhn – D.M. Burns – A.D. Deconick W.-P. Funk – I. Gardner – S.N.C. Lieu A. Marjanen – L. Painchaud – N.A. Pedersen T. Rasimus – S.G. Richter – M. Scopello J.D. Turner – G. Wurst volume 93 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/nhms Ivan Miroshnikov - 978-90-04-36729-6 Downloaded from Brill.com02/10/2020 03:36:56PM via University of Helsinki The Gospel of Thomas and Plato A Study of the Impact of Platonism on the “Fifth Gospel” By Ivan Miroshnikov LEIDEN | BOSTON Ivan Miroshnikov - 978-90-04-36729-6 Downloaded from Brill.com02/10/2020 03:36:56PM via University of Helsinki This title is published in Open Access with the support of the University of Helsinki Library. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. -

Nor Hawani Salikin

Characterisation of a novel antinematode agent produced by the marine epiphytic bacterium Pseudoalteromonas tunicata and its impact on Caenorhabditis elegans Nor Hawani Salikin A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences Faculty of Science August 2020 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname/Family Name : Salikin Given Name/s : Nor Hawani Abbreviation for degree as give in the University : Ph.D. calendar Faculty : UNSW Faculty of Science School : School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences Characterisation of a novel antinematode agent produced Thesis Title : by the marine epiphytic bacterium Pseudoalteromonas tunicata and its impact on Caenorhabditis elegans Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) Drug resistance among parasitic nematodes has resulted in an urgent need for the development of new therapies. However, the high re-discovery rate of antinematode compounds from terrestrial environments necessitates a new repository for future drug research. Marine epiphytic bacteria are hypothesised to produce nematicidal compounds as a defence against bacterivorous predators, thus representing a promising, yet underexplored source for antinematode drug discovery. The marine epiphytic bacterium Pseudoalteromonas tunicata is known to produce a number of bioactive compounds. Screening genomic libraries of P. tunicata against the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans identified a clone (HG8) showing fast-killing activity. However, the molecular, chemical and biological properties of HG8 remain undetermined. A novel Nematode killing protein-1 (Nkp-1) encoded by an uncharacterised gene of HG8 annotated as hp1 was successfully discovered through this project. The Nkp-1 toxicity appears to be nematode-specific, with the protein being highly toxic to nematode larvae but having no impact on nematode eggs. -

See Who Attended

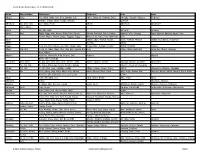

Company Name First Name Last Name Job Title Country 24Sea Gert De Sitter Owner Belgium 2EN S.A. George Droukas Data analyst Greece 2EN S.A. Yannis Panourgias Managing Director Greece 3E Geert Palmers CEO Belgium 3E Baris Adiloglu Technical Manager Belgium 3E David Schillebeeckx Wind Analyst Belgium 3E Grégoire Leroy Product Manager Wind Resource Modelling Belgium 3E Rogelio Avendaño Reyes Regional Manager Belgium 3E Luc Dewilde Senior Business Developer Belgium 3E Luis Ferreira Wind Consultant Belgium 3E Grégory Ignace Senior Wind Consultant Belgium 3E Romain Willaime Sales Manager Belgium 3E Santiago Estrada Sales Team Manager Belgium 3E Thomas De Vylder Marketing & Communication Manager Belgium 4C Offshore Ltd. Tom Russell Press Coordinator United Kingdom 4C Offshore Ltd. Lauren Anderson United Kingdom 4Cast GmbH & Co. KG Horst Bidiak Senior Product Manager Germany 4Subsea Berit Scharff VP Offshore Wind Norway 8.2 Consulting AG Bruno Allain Président / CEO Germany 8.2 Consulting AG Antoine Ancelin Commercial employee Germany 8.2 Monitoring GmbH Bernd Hoering Managing Director Germany A Word About Wind Zoe Wicker Client Services Manager United Kingdom A Word About Wind Richard Heap Editor-in-Chief United Kingdom AAGES Antonio Esteban Garmendia Director - Business Development Spain ABB Sofia Sauvageot Global Account Executive France ABB Jesús Illana Account Manager Spain ABB Miguel Angel Sanchis Ferri Senior Product Manager Spain ABB Antoni Carrera Group Account Manager Spain ABB Luis andres Arismendi Gomez Segment Marketing Manager Spain -

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research

Given Name Alternatives for Irish Research Name Abreviations Nicknames Synonyms Irish Latin Abigail Abig Ab, Abbie, Abby, Aby, Bina, Debbie, Gail, Abina, Deborah, Gobinet, Dora Abaigeal, Abaigh, Abigeal, Gobnata Gubbie, Gubby, Libby, Nabby, Webbie Gobnait Abraham Ab, Abm, Abr, Abe, Abby, Bram Abram Abraham Abrahame Abra, Abrm Adam Ad, Ade, Edie Adhamh Adamus Agnes Agn Aggie, Aggy, Ann, Annot, Assie, Inez, Nancy, Annais, Anneyce, Annis, Annys, Aigneis, Mor, Oonagh, Agna, Agneta, Agnetis, Agnus, Una Nanny, Nessa, Nessie, Senga, Taggett, Taggy Nancy, Una, Unity, Uny, Winifred Una Aidan Aedan, Edan, Mogue, Moses Aodh, Aodhan, Mogue Aedannus, Edanus, Maodhog Ailbhe Elli, Elly Ailbhe Aileen Allie, Eily, Ellie, Helen, Lena, Nel, Nellie, Nelly Eileen, Ellen, Eveleen, Evelyn Eibhilin, Eibhlin Helena Albert Alb, Albt A, Ab, Al, Albie, Albin, Alby, Alvy, Bert, Bertie, Bird,Elvis Ailbe, Ailbhe, Beirichtir Ailbertus, Alberti, Albertus Burt, Elbert Alberta Abertina, Albertine, Allie, Aubrey, Bert, Roberta Alberta Berta, Bertha, Bertie Alexander Aler, Alexr, Al, Ala, Alec, Ales, Alex, Alick, Allister, Andi, Alaster, Alistair, Sander Alasdair, Alastar, Alsander, Alexander Alr, Alx, Alxr Ec, Eleck, Ellick, Lex, Sandy, Xandra, Zander Alusdar, Alusdrann, Saunder Alfred Alf, Alfd Al, Alf, Alfie, Fred, Freddie, Freddy Albert, Alured, Alvery, Avery Ailfrid Alberedus, Alfredus, Aluredus Alice Alc Ailse, Aisley, Alcy, Alica, Alley, Allie, Allison, Alicia, Alyssa, Eileen, Ellen Ailis, Ailise, Aislinn, Alis, Alechea, Alecia, Alesia, Aleysia, Alicia, Alitia Ally, -

Epiphany 2021

FATHER AARON M. WILLIAMS Solemnity of the Epiphany of the Lord 3 January 2021 A few days before Christmas, I’m sure you saw in the news about the sighting of the ‘Christmas Star’—the result of the conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn in the night’s sky. I know a lot of people went out to look at it that night, but even in Greenville, you can’t really get a good look at the stars unless you drive out of town where the city lights fade into darkness. That’s the odd thing about the night sky. Each of those stars are massive, in reality. Some of them are larger than our sun, but because they are so far away their light can be overcome by a street lamp, and they entirely disappear. The Magi, we are told, followed a star. Saint Matthew calls them μάγοι1, which really is the root of our English word ‘magician’. These men were astrologers, though we like to think of them like kings. The reality is that they most likely were not the sort of people we imagine them to be, they aren’t really even scientists who would have studied the stars. The magi were astrologists—they were the sort of people that the Scripture tells us not to associate with, those who are attempting to divine the future by looking at the stars. Which makes their appearance in Saint Matthew’s gospel all the more interesting, especially since they are portrayed in a good light. That is not the same situation for the character of ‘Simon Magus’— Simon the Magician who Saint Peter rebukes in the Acts of the Apostles for his astrology and witchcraft. -

Surname First Name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen

2018 DRIVERS' CATEGORISATION LIST Updated on 09/07/2018 Drivers in red : revised categorisation Drivers in blue : new categorisation Surname First name Categorisation Abadin Jose Luis Silver Abbelen Klaus Bronze Abbott Hunter Silver Abbott James Silver Abe Kenji Bronze Abelli Julien Silver Abergel Gabriele Bronze Abkhazava Shota Bronze Abra Richard Silver Abreu Attila Gold Abril Vincent Gold Abt Christian Silver Abt Daniel Gold Accary Thomas Silver Acosta Hinojosa Julio Sebastian Silver Adam Jonathan Platinum Adams Rudi Bronze Adorf Dirk Silver Aeberhard Juerg Silver Afanasiev Sergei Silver Agostini Riccardo Gold Aguas Rui Gold Ahlin-Kottulinsky Mikaela Silver Ahrabian Darius Bronze Ajlani Karim Bronze Akata Emin Bronze Aksenov Stanislas Silver Al Faisal Abdulaziz Silver Al Harthy Ahmad Silver Al Masaood Humaid Bronze Al Qubaisi Khaled Bronze Al-Azhari Karim Bronze Alberico Neil Silver Albers Christijan Platinum Albert Michael Silver Albuquerque Filipe Platinum Alder Brian Silver Aleshin Mikhail Platinum Alesi Giuliano Silver Alessi Diego Silver Alexander Iradj Silver Alfaisal Saud Bronze Alguersuari Jaime Platinum Allegretta Vincent Silver Alleman Cyndie Silver Allemann Daniel Bronze Allen James Silver Allgàuer Egon Bronze Allison Austin Bronze Allmendinger AJ Gold Allos Manhal Bronze Almehairi Saeed Silver Almond Michael Silver Almudhaf Khaled Bronze Alon Robert Silver Alonso Fernando Platinum Altenburg Jeff Bronze Altevogt Peter Bronze Al-Thani Abdulrahman Silver Altoè Giacomo Silver Aluko Kolawole Bronze Alvarez Juan Cruz Silver Alzen -

Sophia: the Gnostic Heritage John F

Fall 2009 Sophia: the Gnostic Heritage John F. Nash Summary ther,” “Lord,” and so forth. Resistance has also increased to the custom of envisioning his article presents a brief history of God in any kind of anthropomorphic terms.2 TSophia, best known of the divine feminine Yet anthropomorphism is comforting to many individualities of the West. Under her Hebrew people, and the concept of a powerful God- name, Chokmah, Sophia emerged in late bibli- dess, complementing or even replacing the cal times. But it was the Gnostics of the early traditional masculine God, resonates with large Christian era who created the Sophia we rec- numbers of thinking people. ognize today. Sophia played a small but sig- nificant role in western mainstream Christian- Of all the anthropomorphized, feminine deities ity and a much larger role in Eastern Ortho- discussed today, Sophia is the most popular in doxy. Russian Orthodox theologians not only the West, to judge by the literature of feminist had personal experiences of Sophia but also theology, women’s studies, and New Age cul- shared important insights into how she related ture. The purpose of this article, then, is to to the Trinity and to the “invisible Church” present a brief review of the history and con- that transcends historical Christianity. The temporary relevance of Sophia in western article concludes with some remarks about the spirituality. Many questions remain concern- relevance of Sophia in modern spirituality. ing how Sophia can be reconciled with tradi- tional Christian doctrine. However, opportuni- Background ties also exist to integrate Sophia more firmly into the Trans-Himalayan teachings. -

Courier 2-19-17

February 19, 2017 The Cathedral Courier 4 February 19, 2017 Cathedral of St. Joseph Vol. 6, No. 13 Knights of Columbus Famous Fish Fries Campaign Supports Life Flourish Once Again in Il Corriere del Duomo The Knights of Columbus Council 504 in Wheeling will be conducting a Baby Bottle Campaign during Lent. Baby bottles the Friendly City Weekly Journal for the Cathedral of St. Joseph will be distributed to all interested parishioners after each Mass on Sunday March 5th. The bottles are to be filled with loose St. Alphonsus Parish in Wheeling and St. John change throughout the Lenten season and returned on Palm Parish in Benwood are combining efforts to offer their Feast of the Sunday. All proceeds will be given to a local Crisis Pregnancy Fish Fry beginning on Ash Wednesday, March 1, and Center for the promotion of pro-life activities. continuing on all Fridays during Lent. Parishioners Congratulations Chair of St. from both parishes will be working together to make $"#"&"#!** )$ this a successful event. The Fry will be held at the St. Most. Reverend Michael J. Peter the Alphonsus Parish Hall, 2011 Market Street, Wheeling Bransfield from 11am-6pm. Apostle Menu consists of: Fish Sandwiches, French Fries, on the 12th Anniversary of the Episcopal Ordination Macaroni & Cheese, Cabbage & Noodles, Cole Slaw, St. Peter having triumphed over the devil in the East, pursued him to Rome Desserts and Refreshments. Eat in or take out. To place in the person of Simon Magus. He who an order call 304-905-6589. had formerly trembled at the voice of a This is a cooperative effort between the parishes of poor maid now feared not the very St.