Understanding Small Scale Providers of Sanitation Services: a Case Study of Kibera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kibera: the Biggest Slum in Africa? Amélie Desgroppes, Sophie Taupin

Kibera: The Biggest Slum in Africa? Amélie Desgroppes, Sophie Taupin To cite this version: Amélie Desgroppes, Sophie Taupin. Kibera: The Biggest Slum in Africa?. Les Cahiers de l’Afrique de l’Est, 2011, 44, pp.23-34. halshs-00751833 HAL Id: halshs-00751833 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00751833 Submitted on 14 Nov 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Kibera: The Biggest Slum in Africa? Amélie Desgroppes and Sophie Taupin Abstract This article presents the findings of the estimated population of Kibera, often said to be the “biggest slum in Africa”. This estimation was done in 2009 by the French Institute for Research in Africa (IFRA) Nairobi and Keyobs, a Belgian company, using Geographical Information Systems (GIS) methodology and a ground survey. The results showed that there are 200,000 residents, instead of the 700,000 to 1 million figures which are often quoted. The 2009 census and statistics on Kibera’s population also confirmed that the IFRA findings were accurate. Introduction Kibera, the infamous slum in Nairobi – Kenya’s capital, is viewed as “the biggest, largest and poorest slum in Africa”. -

Population Density and Spatial Patterns of Informal Settlements in Nairobi, Kenya

sustainability Article Population Density and Spatial Patterns of Informal Settlements in Nairobi, Kenya Hang Ren 1,2 , Wei Guo 3 , Zhenke Zhang 1,2,*, Leonard Musyoka Kisovi 4 and Priyanko Das 1,2 1 Center of African Studies, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210046, China; [email protected] (H.R.); [email protected] (P.D.) 2 School of Geography and Ocean Science, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China 3 Department of Social Work and Social Policy, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210023, China; [email protected] 4 Department of Geography, Kenyatta University, Nairobi 43844, Kenya; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-025-89686694 Received: 21 August 2020; Accepted: 15 September 2020; Published: 18 September 2020 Abstract: The widespread informal settlements in Nairobi have interested many researchers and urban policymakers. Reasonable planning of urban density is the key to sustainable development. By using the spatial population data of 2000, 2010, and 2020, this study aims to explore the changes in population density and spatial patterns of informal settlements in Nairobi. The result of spatial correlation analysis shows that the informal settlements are the centers of population growth and agglomeration and are mostly distributed in the belts of 4 and 8 km from Nairobi’s central business district (CBD). A series of population density models in Nairobi were examined; it showed that the correlation between population density and distance to CBD was positive within a 4 km area, while for areas outside 8 km, they were negatively related. The factors determining population density distribution are also discussed. We argue that where people choose to settle is a decision process between the expected benefits and the cost of living; the informal settlements around the 4-km belt in Nairobi has become the choice for most poor people. -

End of 2016 Issue| Issue 10

UHDA NEWS UHDA Newsletter END OF 2016 ISSUE| ISSUE 10 INSIDE: Welcome Note Woodley Ward The Informal Traders UHDA 2016 Highlights UHDA Members & Partners Photo by Sebastian Wanzilla Welcome Note We mark the end of the year with two recent members joining ; The British High Commission and The Nairobi Hospital, totaling our 2016 membership to 46 property owners. This year we have forged additional partnerships with various institutions to not only enhance the membership but also strengthen the Upper Hill community. The institutions include; Kenya Power, Upper Hill Secondary and Kibera Sub County Administration. 2016 can be summed up as our most aggressive year yet since our inception 15 years ago. In this edition, we have included some of the year’s highlights that were made possible by your support and contribution. As we gear up for 2017, you can be assured that we intend to keep this momentum and make Upper Hill the best place to live and do business. Borrowing a leaf from Rwanda, we plan to hold a street clean up in January 2017 to kick off the year. The clean up is aimed to clean Upper Hill and also bring the community together. This clean up is also in line with what was discussed in the June 2016 brainstorming session. The long awaited Upper Hill marketing video has been shot and is set to be unveiled in early January 2017. The video was also part of the discussion in the brainstorming session. For now, we take the opportunity to thank all our members and partners for the immense support we have received this year. -

Slum Toponymy in Nairobi, Kenya a Case Study Analysis of Kibera

Urban and Regional Planning Review Vol. 4, 2017 | 21 Slum toponymy in Nairobi, Kenya A case study analysis of Kibera, Mathare and Mukuru Melissa Wangui WANJIRU*, Kosuke MATSUBARA** Abstract Urban informality is a reality in cities of the Global South, including Sub-Saharan Africa, which has over half the urban population living in informal settlements (slums). Taking the case of three informal settlements in Nairobi (Kibera, Mathare and Mukuru) this study aimed to show how names play an important role as urban landscape symbols. The study analyses names of sub-settlements (villages) within the slums, their meanings and the socio-political processes behind them based on critical toponymic analysis. Data was collected from archival sources, focus group discussion and interviews, newspaper articles and online geographical sources. A qualitative analysis was applied on the village names and the results presented through tabulations, excerpts and maps. Categorisation of village names was done based on the themes derived from the data. The results revealed that village names represent the issues that slum residents go through including: social injustices of evictions and demolitions, poverty, poor environmental conditions, ethnic groupings among others. Each of the three cases investigated revealed a unique toponymic theme. Kibera’s names reflected a resilient Nubian heritage as well as a diverse ethnic composition. Mathare settlements reflected political struggles with a dominance of political pioneers in the village toponymy. Mukuru on the other hand, being the newest settlement, reflected a more global toponymy-with five large villages in the settlement having foreign names. Ultimately, the study revealed that ethnic heritage and politics, socio-economic inequalities and land injustices as well as globalization are the main factors that influence the toponymy of slums in Nairobi. -

National-Geographic-2020-Nairobi

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/04/nairobi-coronavirus-quarantine-luxury-few-afford.html © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society, © 2015- 2021 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved H I S T O R Y & C U L T U R E D I S P A T C H E S In Nairobi, quarantine is a luxury few can afford As COVID-19 takes hold in Kenya’s capital, hundreds of thousands living in cramped informal settlements are especially vulnerable. S T O R Y A N D P H O T O G R A P H S B Y N I C H O L E S O B E C K I P U B L I S H E D A P R I L 1 0 , 2 0 2 0 A version of this story appears in the July 2020 issue of National Geographic magazine. Nairobi, Kenya— Driving through Kenya’s capital city during the time of coronavirus is like moving between two disconnected realities. Neighborhoods such as Muthaiga and Karen are silent—their streets deserted, their occupants invisible inside lush compounds, their houses well stocked with food and other necessities. A few miles southwest of downtown is Kibera, home to a quarter of a million people surviving together beneath tin roofs. Kibera is the largest of the more than a hundred informal settlements in Nairobi, where the vast majority of people scrape by on no more than a few dollars a day. Kenya is one of the world’s most unequal societies. Less than 0.1 percent of the country’s 53 million people own more wealth than the other 99.9 percent. -

Umande Trust Bio-Centre Approach in Slum Upgrading Aidah Binale

Umande Trust Bio-Centre Approach in Slum Upgrading Aidah Binale To cite this version: Aidah Binale. Umande Trust Bio-Centre Approach in Slum Upgrading. Les cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est, IFRA Nairobi, 2011, p.167-p.186. halshs-00755905 HAL Id: halshs-00755905 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00755905 Submitted on 22 Nov 2012 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Umande Trust Bio-Centre Approach in Slum Upgrading Aidah Binale Abstract The aim of this article is to present a case study of bio-centres in three slums in Nairobi: Korogocho, Kibera and Mukuru in an approach developed by Umande Trust (UT) which is seeking to improve access to basic urban services to affected communities. To-date, 49 bio-centres have also been constructed in Kisumu and Nairobi. It is hoped that this approach will attract future replication of the technology in other parts of the country. This article gives a background to the Trust and outlines the objectives, strategies, successes and challenges experienced in the course of this slum upgrading effort. Background Umande Trust (UT) is a rights-based agency which believes that modest resources can significantly improve access to water and sanitation services if financial resources are strategically invested in support of community-led plans and actions. -

Home of Last Resort: Urban Land Conflict and the Nubians in Kibera, Kenya

http://www.diva-portal.org Postprint This is the accepted version of a paper published in Urban Studies. This paper has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof-corrections or journal pagination. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Elfversson, E., Höglund, K. (2017) Home of last resort: Urban land conflict and the Nubians in Kibera, Kenya. Urban Studies https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017698416 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-319413 Home of last resort: Urban land conflict and the Nubians in Kibera, Kenya Emma Elfversson and Kristine Höglund Abstract Amid expansive and often informal urban growth, conflict over land has become a severe source of instability in many cities. In slum areas, policies intended to alleviate tensions, including upgrading programs, the legal regulation of informal tenure arrangements, and the reform of local governance structures, have had the unintended consequence of also spurring violence and conflict. This paper analyzes the conflict over a proposed ‘ethnic homeland’ for the Nubian community in the Kibera slum in Nairobi, Kenya, in order to advance knowledge on the strategies communities adopt to promote their interests and how such strategies impact on urban conflict management. Theoretically, we apply the perspective of ‘institutional bricolage’, which captures how actors make use of existing formal and informal structures in pragmatic ways to meet their conflict management needs. While previous research focuses primarily on how bricolage can facilitate cooperation, the case analysis uncovers how over time, the land issue has become closely intertwined with claims of identity and citizenship and a political discourse drawn along ethnic lines. -

Sadili Oval Goals for Peace Report

L LANGA UA T N A N A E U Y G O A U 4th E T H L S O C C E R u10 goals u12 for peace u14 report O Kitengela Rd, Nxt to Malezi School, Langata PO Box 51736 - 00200 Nairobi - Kenya, Tel: 254 20 609046, Fax: 254 20 609372 Email: [email protected] Web: www.sadili.com LIST OF SPONSORS FOR THE LANGATA YOUTH SOCCER LEAGUE 2008 Member of Parliament for Lang’ata, Rt. Hon. Raila Amolo Odinga, Patron of the Annual Lang’ata Youth Soccer League and the following Friends: 1. The Tamarind Group, Attention: Mr. Martin Dunford, 14. Managing Director, AMREF Country Office, P. O. Box Executive Chairman, P. O. Box 74493, Nairobi 00200, 3025-001, Nairobi Kenya 15. Mr. Adan, Managing Director, Barclays Bank (K)Ltd., P. O. 2. Mr. David Otieno, Safety Health and Environment Box 30120, Nairobi Manager, Barclays Bank, Commercial Services 16. Malezi Foundation, Chairman, Mr. James Abok Odera, P. Department., Fedha Towers, Muindi Mbingu St., 9th O. Box 51736-00200, Nairobi, Kenya Floor, P. O. Box 30120, 00100, GPO. 17. United States Embassy in Kenya, His Excellency, 3. Mabati Rolling Mills Ltd, Attention: Mr. Tony Nasirembe, Ambassador Ranneburger. P. O. Box 271, Athi River, Kenya 18. The Mayor, Nairobi City Council 4. Officer In-Charge, Nairobi West Prison, Attention: SSP M.M. Ngunjiri 19. The President, International Olympic Committee, His Excellency Jacques Rogge 5. United Nations Environment Programme Regional Office for Africa, Attention: Mr. Henry Ndede 20. Minister for Youth and Sports, Hon. Prof. Helen Sambili 21. -

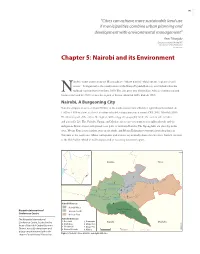

Chapter 5: Nairobi and Its Environment

145 “Cities can achieve more sustainable land use if municipalities combine urban planning and development with environmental management” -Ann Tibaijuki Executive Director UN-HABITAT Director General UNON 2007 (Tibaijuki 2007) Chapter 5: Nairobi and its Environment airobi’s name comes from the Maasai phrase “enkare nairobi” which means “a place of cool waters”. It originated as the headquarters of the Kenya Uganda Railway, established when the Nrailhead reached Nairobi in June 1899. The city grew into British East Africa’s commercial and business hub and by 1907 became the capital of Kenya (Mitullah 2003, Rakodi 1997). Nairobi, A Burgeoning City Nairobi occupies an area of about 700 km2 at the south-eastern end of Kenya’s agricultural heartland. At 1 600 to 1 850 m above sea level, it enjoys tolerable temperatures year round (CBS 2001, Mitullah 2003). The western part of the city is the highest, with a rugged topography, while the eastern side is lower and generally fl at. The Nairobi, Ngong, and Mathare rivers traverse numerous neighbourhoods and the indigenous Karura forest still spreads over parts of northern Nairobi. The Ngong hills are close by in the west, Mount Kenya rises further away in the north, and Mount Kilimanjaro emerges from the plains in Tanzania to the south-east. Minor earthquakes and tremors occasionally shake the city since Nairobi sits next to the Rift Valley, which is still being created as tectonic plates move apart. ¯ ,JBNCV 5IJLB /BJSPCJ3JWFS .BUIBSF3JWFS /BJSPCJ3JWFS /BJSPCJ /HPOH3JWFS .PUPJOF3JWFS %BN /BJSPCJ%JTUSJDUT /BJSPCJ8FTU Kenyatta International /BJSPCJ/BUJPOBM /BJSPCJ/PSUI 1BSL Conference Centre /BJSPCJ&BTU The Kenyatta International /BJSPCJ%JWJTJPOT Conference Centre, located in the ,BTBSBOJ 1VNXBOJ ,BKJBEP .BDIBLPT &NCBLBTJ .BLBEBSB heart of Nairobi's Central Business 8FTUMBOET %BHPSFUUJ 0510 District, has a 33-story tower and KNBS 2008 $FOUSBM/BJSPCJ ,JCFSB Kilometres a large amphitheater built in the Figure 1: Nairobi’s three districts and eight divisions shape of a traditional African hut. -

Mathare Slum

Standards of Living - Mathare Valley, Kenya Missions of Hope International Standards of Living - Mathare Slum Kenya is a beautiful country, well known for the many game parks and wild animals that abound throughout the country. However, Kenya is home to two of the largest slums in Africa, Kibera and Mathare. It is estimated that 800,000 people live in Mathare in an area of less than a square mile. Most live on an income of less than a dollar per day. Crime and HIV/AIDs are common. Many parents die of AIDS and leave their children to fend for themselves. Missions of Hope tries to care for as many of these orphans as possible, but their resources are limited. Mathare Facts: • 70% of Nairobi's population of four million lives on 5% of the of the city's land area. • Mathare contains a population greater than the cities of Seattle, Denver, or Boston, yet the slum covers an area of less than a square mile. In comparison, Seattle covers 142 square miles, Boston 89 square miles, and Denver 154 square miles. • 40% are HIV positive. • The average life expectancy for a person who is HIV positive in Mathare is five years or less. • Common health problems for children in Mathare include dysentery, malnutrition, malaria, typhoid, cholera, infections, tetanus, and polio. • Juvenile heads of households are common. (A child or teen is left to care for younger siblings, since both parents have died of AIDS.) Mathare has no police or fire protection, and no paved roads. • There are an estimated 70,000 children in the Mathare, with only 3-4 public schools to educate them. -

SHINING HOPE for COMMUNITIES 2018 ANNUAL REPORT Systemic Change Starts at the Grassroots

SHINING HOPE FOR COMMUNITIES 2018 ANNUAL REPORT Systemic Change Starts at the Grassroots shofco.org @hope2shine Shining Hope for Communities @Shofco History Kennedy Odede founded SHOFCO in 2004 while growing up in Kibera, Africa’s largest urban slum. Today, SHOFCO serves more than 350,000 urban slum dwellers in eight slums across two cities in Kenya. We work to disrupt survival mode and build a promising future for urban slum dwellers, with a focus on women and children as the key to community transformation. To achieve this, we are pioneering service delivery systems in urban slums that provide a channel for investment by the government and involvement by other service providers. Our goal is to reach 1 million beneficiaries with dignified access to critical services by 2030. Vision Building Urban Promise from Urban Poverty Mission Shining Hope for Communities (SHOFCO) is a grassroots movement that catalyzes large scale transformation in urban slums by providing critical services for all, community advocacy platforms, and education and leadership development for women and girls. Table of Contents Foreword 1 Service Areas 2 SHOFCO in Numbers 3 Achievements 4 Girls’ Leadership and Education 5 Early Childhood Development 7 Adult Literacy 8 Health 9 10 Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) 11 Sustainable Livelihoods (SL) 13 Gender Based Violence (GBV) Community Centers and Libraries 14 SHOFCO Urban Network (SUN) 15 Partners 16 Financials 18 Donors and Sponsors 19 Leadership 22 Foreword Dear Friends, I am excited to share our 2018 Annual Report with you. 2018 was a year of new arrivals for SHOFCO, filled with milestones that rippled across Kibera and all eight urban slums where we reached over 350,000 people. -

Kibera Evaluation Report FINAL.Pdf

Progress and Promise: Innovations in Slum Upgrading a Post-Project Intervention Assessment Report Nairobi 2014 KIBERA INTEGRATED WATER SANITATION AND WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT Progress and Promise: Innovations in Slum Upgrading Post-Project Intervention Assessment Report KIBERA INTEGRATED WATER SANITATION AND WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT Progress and Promise: Innovations in Slum Upgrading United Nations Human Settlements Programme Nairobi 2014 First published in Nairobi in 2014 by UN-Habitat. Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme 2014 All rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-Habitat) P. O. Box 30030, 00100 Nairobi GPO KENYA Tel: 254-020-7623120 (Central Office) www.unhabitat.org HS Number: HS/057/14E Disclaimer The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of he United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area r of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers of boundaries. Views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme, the United Nations, or its Member States. Excerpts may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. Front cover photos: UN-Habitat Principal author: Thomas Meredith and Melanie MacDonald Contributors: Graham Alabaster Publication coordinator: Harrison Kwach and Daniel Adom Editor: Graham Alabaster Design and layout: Freddie Maitaria Printer: UNON, Publishing Services Section, Nairobi ISO 14001:2004-certified Progress and Promise: Innovations in Slum Upgrading iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This report is part of a larger study of the impact who worked with implementing partners and to of K-WATSAN and KENSUP in Soweto East.