The Ramayana of Välmlki

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

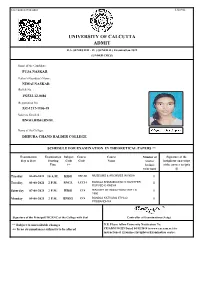

University of Calcutta Admit

532/1800865758/0401 5320942 UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA ADMIT B.A. SEMESTER - IV ( GENERAL) Examination-2021 (UNDER CBCS) Name of the Candidate : PUJA NASKAR Father's/Guardian's Name : NIMAI NASKAR Roll & No. : 192532-12-0486 Registration No. 532-1212-1106-19 Subjects Enrolled : BNGG,HISG,BNGL Name of the College : DHRUBA CHAND HALDER COLLEGE SCHEDULE FOR EXAMINATION IN THEORETICAL PAPERS ** Examination Examination Subject Course Course Number of Signature of the Day & Date Starting Code Code Name Answer invigilator on receipt Time ++ book(s) of the answer script/s to be used @ Tuesday 03-08-2021 10 A.M. HISG SEC-B1 MUSEUMS & ARCHIVES IN INDIA 1 Tuesday 03-08-2021 2 P.M. BNGL LCC2-1 BANGLA BHASABIGYAN O SAHITYER 1 RUPVED O KABYA Saturday 07-08-2021 2 P.M. HISG CC4 HISTORY OF INDIA FROM 1707 TO 1 1950 Monday 09-08-2021 2 P.M. BNGG CC4 BANGLA KATHASAHITYA O 1 PROBANDHYA Signature of the Principal/TIC/OIC of the College with Seal Controller of Examinations (Actg.) ** Subject to unavoidable changes N.B. Please follow University Notification No. ++ In no circumstances subject/s to be altered CE/ADM/18/229 Dated 04/12/2018 in www.cuexam.net for instruction of Examinee/Invigilator/Examination centre. 532/1800908303/0402 5320963 UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA ADMIT B.A. SEMESTER - IV ( GENERAL) Examination-2021 (UNDER CBCS) Name of the Candidate : JABA MONDAL Father's/Guardian's Name : SUBARNA MONDAL Roll & No. : 192532-12-0487 Registration No. 532-1212-1126-19 Subjects Enrolled : HISG,SOCG,BNGL Name of the College : DHRUBA CHAND HALDER COLLEGE SCHEDULE FOR EXAMINATION IN THEORETICAL PAPERS ** Examination Examination Subject Course Course Number of Signature of the Day & Date Starting Code Code Name Answer invigilator on receipt Time ++ book(s) of the answer script/s to be used @ Tuesday 03-08-2021 10 A.M. -

Jabali's Reasoning

“Om Sri Lakshmi Narashimhan Nahama” Valmiki Ramayana – Ayodhya Kanda – Chapter 108 Jabali’s Reasoning Summary A Brahmana named Jabali tries to persuade Rama to accept the kingdom by advocating the theory of Nastikas (non-believers), saying that he need not get attached to his father's words and remain in the troublesome forest. Jabali requests Rama to enjoy the royal luxuries, by accepting the crown. Chapter [Sarga] 108 in Detail aashvaasayantam bharatam jaabaalir braahmana uttamah | uvaaca raamam dharmajnam dharma apetam idam vacah || 2-108-1 A Brahmana called Jabali spoke the following unrighteous words to Rama, who knew righteousness and who was assuaging Bharata as aforesaid saadhu raaghava maa bhuut te buddhir evam nirarthakaa | praakritasya narasya iva aarya buddheh tapasvinah || 2-108-2 "Enough, O Rama! Let not your wisdom be rendered void like a common man, you who are distinguished for your intelligence and virtue." kah kasya purusho bandhuh kim aapyam kasya kenacit | yad eko jaayate jantur eka eva vinashyati || 2-108-3 "Who is related to whom? What is there to be obtained by anything and by whom? Every creature is born alone and dies alone." tasmaan maataa pitaa ca iti raama sajjeta yo narah | unmatta iva sa jneyo na asti kaacidd hi kasyacit || 2-108-4 "O, Rama! He who clings to another, saying, 'This is my father, this is my mother, he should be known as one who has lost his wits. There is none who belongs to another." Page 1 of 4 “Om Sri Lakshmi Narashimhan Nahama” Valmiki Ramayana – Ayodhya Kanda – Chapter 108 yathaa graama antaram gagccan narah kashcid kvacid vaset | utsrijya ca tam aavaasam pratishtheta apare ahani || 2-108-5 evam eva manushyaanaam pitaa maataa griham vasu | aavaasa maatram kaakutstha sajjante na atra sajjanaah || 2-108-6 "O, Rama! As one who passes the a strange village spends the night the and the next day leaves that place and continues his journey, so are mother, father, home and possessions to a man; they are but a resting place. -

HMH Social Studies for California (Grades 6–8) 1

Review of HMH Social Studies for California (Grades 6–8) 1 Review of HMH Social Studies for California (Grades 6–8) Hindu Education Foundation USA (HEF) July, 2017 Note: This document contains the following. The first part (Page 2 through 12) describes the different problems in the HMH Social Studies for California (Grades 6–8) textbook draft in detail. The Appendix 1 (Page 13 through 16) lists the violations in the textbook drafts as per the categories suggested in History–Social Science Adoption Program Evaluation Map for quick reference of all citations that are raised through this document. Review of HMH Social Studies for California (Grades 6–8) 2 This is a review of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt’s program for middle school named the HMH Social Studies for California (Grades 6–8)1. The textbook drafts being considered have several instances of adverse reflections on Hinduism and India in the textbook which violate the Californian Law and Educational standards. We see that the narrative in textbook draft reflects many Orientalist biases. It is important to note that the Evaluation criteria for Instructional Material require the textbooks “to project the cultural diversity of society; instill in each child a sense of pride in his or her heritage; develop a feeling of self-worth related to equality of opportunity; eradicate the roots of prejudice; and thereby encourage the optimal individual development of each student”. They also prohibit any “Descriptions, depictions, labels, or rejoinders that tend to demean, stereotype, or patronize minority groups.”2 Our review shows that the drafts do not completely adhere to these provisions. -

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 5, Issue 4 April 2011

OM NAMO BHAGAVATE PANDURANGAYA BALAJI VANI Volume 5, Issue 4 April 2011 HARI OM March 1st, Swamiji returned from India where he visited holy places and sister branch in Bangalore. And a fruitful trip to Maha Sarovar (West Kolkata) water to celebrate Mahashivatri here in our temple Sunnyvale. Shiva Abhishekham was performed every 3 hrs with milk, yogurt, sugar, juice and other Dravyas. The temple echoed with devotional chanting of Shiva Panchakshari Mantram, Om Namah Shivayah. During day long Pravachan Swamiji narrated 2 special stories. The first one was about Ganga, and why we pour water on top of Shiva Linga and the second one about Bhasmasura. King Sagar performed powerful Ashwamedha Yagna (Horse sacrifice) to prove his supremacy. Lord Indra, leader of the Demi Gods, fearful of the results of the yagna, stole the horse. He left the horse at the ashram of Kapila who was in deep meditation. King Sagar's 60,000 sons (born to Queen Sumati) and one son Asamanja (born to queen Keshini) were sent to search the horse. When they found the horse at Shri N. Swamiji performing Aarthi KapilaDeva's Ashram, they concluded he had stolen it and prepared to attack him. The noise disturbed the meditating Rishi/Sage VISAYA VINIVARTANTE NIRAHARASYA DEHINAH| KapilaDeva and he opened his eyes and cursed the sons of king sagara for their disrespect to such a great personality. Fire emanced RASAVARJAM RASO PY ASYA from their own bodies and they were burned to ashes instantly. Later PARAM DRSTVA NIVARTATE || king Sagar sent his Grandson Anshuman to retreive the horse. -

Multidimensional Role of Women in Shaping the Great Epic Ramayana

International Journal of Academic Research and Development International Journal of Academic Research and Development ISSN: 2455-4197 Impact Factor: RJIF 5.22 www.academicsjournal.com Volume 2; Issue 6; November 2017; Page No. 1035-1036 Multidimensional role of women in shaping the great epic Ramayana Punit Sharma Assistant Professor, Institute of Management & Research IMR Campus, NH6, Jalgaon, Maharashtra, India Abstract We look for role models all around, but the truth is that some of the greatest women that we know of come from Indian mythology Ramayana. It is filled with women who had the fortitude and determination to stand up against all odds ones who set a great example for generations to come. Ramayana is full of women, who were mentally way stronger than the glorified heroes of this great Indian epic. From Jhansi Ki Rani to Irom Sharmila, From Savitribai Fule to Sonia Gandhi and From Jijabai to Seeta, Indian women have always stood up for their rights and fought their battles despite restrictions and limitations. They are the shining beacons of hope and have displayed exemplary dedication in their respective fields. I have studied few characters of Ramayana who teaches us the importance of commitment, ethical values, principles of life, dedication & devotion in relationship and most importantly making us believe in women power. Keywords: ramayana, seeta, Indian mythological epic, manthara, kaikeyi, urmila, women power, philosophical life, mandodari, rama, ravana, shabari, surpanakha Introduction Scope for Further Research The great epic written by Valmiki is one epic, which has Definitely there is a vast scope over the study for modern day mentioned those things about women that make them great. -

Kaveri – 2019 Annual Day Script Bala Kanda: Rama

Kaveri – 2019 Annual Day Script Bala Kanda: Rama marries Sita by breaking the bow of Shiva Janaka: I welcome you all to Mithila! As you see in front of you, is the bow of Shiva. Whoever is able to break this bow of Shiva shall wed my daughter Sita. Prince 1: Bows to the crowd and tries to lift the bow and is unsuccessful Prince 2: Bows to the crowd and tries to lift the bow and is unsuccessful Rama 1: Bows, prays to the bow, lifts it, strings it and pulls the string back and bends and breaks it Janaka: By breaking Shiva’s bow, Rama has won the challenge and Sita will be married to Rama the prince of Ayodhya. Ayodhya Kanda: Narrator: Rama, Sita, Lakshmana, Shatrugna, Bharata are all married in Mithila and return to Ayodhya and lived happily for a number of years. Ayodhya rejoiced and flourished under King Dasaratha and the good natured sons of the King. King Dasaratha felt it was time to crown Rama as the future King of Ayodhya. Dasaratha: Rama my dear son, I have decided that you will now become the Yuvaraja of Ayodhya and I would like to advice you on how to rule the kingdom. Rama 2: I will do what you wish O father! Let me get your blessings and mother Kausalya’s blessings. (Rama bows to Dasaratha and goes to Kausalya) Kausalya: Rama, I bless you to rule this kingdom just like your father. Narrator: In the mean time, Manthara, Kaikeyi’s maid hatches out an evil plan. -

Also Known As Is the Most Important and Earliest Metrical Work of the Texual Tradition of Hinduism. This Is the Most Authorit

Written by : Dr. K.R. Kumudavalli, H.O.D of Sanskrit, Vijaya College, R.V. Road, Bangalore-4 मनुमत:ृ मनुमतृ also known as मानवधम शा is the most important and earliest metrical work of the धम शा texual tradition of Hinduism. This मनुमतृ is the most authoritative work on Hindu law which is supposed to be compiled between 2 nd Century B.C. and 2 nd Century A.D. Manu is not the name of one person. A number of Manus are mentioned in Puranas which differ in the names and number of Manus. For Eg. The वाय ु and प Puranas refers to 14 no. of Manus. वण ु and माड Puranas tell about 12 no. of Manus. Manu may be regarded as a legendary sage with whom law is associated. No details about the life of Manu are known. Generally known as the Laws of Manu or Institution of Manu, the text presents itself as a discourse given by Manu, the progenitor of mankind to seers of Rishis, who request him to tell them the ‘Law of all the social classes. Aaccording to Hindu tradition, the मनुमतृ records the words of म . Manu the son of Brahma learns the lessons of the text which consists 1000 chapters on Law, Polity and Pleasure which was given to him by his father. Then he proceeds to teach it to his own students. One among them by name भगृ ु relays this information in the मनुमत,ृ to an audience of his own pupils. Thus it was passed on from generation to generation. -

Chapter 10, Verses 27 to 30,Mandukya

Baghawat Geeta, Class 137: Chapter 10, Verses 30 to 33 Shloka # 30: प्रह्लादश्चास्िम दैत्यानां कालः कलयतामहम्। मृगाणां च मृगेन्द्रोऽहं वैनतेयश्च पक्िषणाम्।।10.30।। Daityanam, among demons, the descendants of Diti, I am the one called Prahlada. And I am kalah, Time; kalayatam, among reckoners of time, of those who calculate. And mrganam, among animals; I am mrgendrah, the loin, or the tiger. And paksinam, among birds; (I am) vainateyah, Garuda, the son of Vinata. Continuing his teaching, Swamiji said, we are seeing Sri Krishna enumerate the glories of Ishwara. The entire creation is a manifestation and glory of the Lord. Sri Krishna chooses a few specialties as his glory. They can be chosen to invoke God. Even though all rivers are glorious, Ganga can be used to invoke god. Hence Ganga is considered scared. Everyone enumerated can be an alambanam. Many are identified from mythological stories. Thus he cites in shloka # 30 about Prahlada. Prahlada stuthi in the Bhagavatham is a very well known sthothram; in which we find the highest Vedanta talked about. In the Bhagavatham there are many stuthis or sthothrams; Dhruva stuthi; Prahlada sthuthi; Kunthi sthuthi; Bhishma sthuthi; each character glorifies the Lord and the beauty is, in those sthothrams not only the puranic glories are there; the highest Vedanta is also packed in those stuthis and among them Prahlada is also a great one. It is an important one because even though Prahlada is born an asura, by his spiritual sadhana he could change his character and become a Gyani. -

The Ramayana by R.K. Narayan

Table of Contents About the Author Title Page Copyright Page Introduction Dedication Chapter 1 - RAMA’S INITIATION Chapter 2 - THE WEDDING Chapter 3 - TWO PROMISES REVIVED Chapter 4 - ENCOUNTERS IN EXILE Chapter 5 - THE GRAND TORMENTOR Chapter 6 - VALI Chapter 7 - WHEN THE RAINS CEASE Chapter 8 - MEMENTO FROM RAMA Chapter 9 - RAVANA IN COUNCIL Chapter 10 - ACROSS THE OCEAN Chapter 11 - THE SIEGE OF LANKA Chapter 12 - RAMA AND RAVANA IN BATTLE Chapter 13 - INTERLUDE Chapter 14 - THE CORONATION Epilogue Glossary THE RAMAYANA R. K. NARAYAN was born on October 10, 1906, in Madras, South India, and educated there and at Maharaja’s College in Mysore. His first novel, Swami and Friends (1935), and its successor, The Bachelor of Arts (1937), are both set in the fictional territory of Malgudi, of which John Updike wrote, “Few writers since Dickens can match the effect of colorful teeming that Narayan’s fictional city of Malgudi conveys; its population is as sharply chiseled as a temple frieze, and as endless, with always, one feels, more characters round the corner.” Narayan wrote many more novels set in Malgudi, including The English Teacher (1945), The Financial Expert (1952), and The Guide (1958), which won him the Sahitya Akademi (India’s National Academy of Letters) Award, his country’s highest honor. His collections of short fiction include A Horse and Two Goats, Malgudi Days, and Under the Banyan Tree. Graham Greene, Narayan’s friend and literary champion, said, “He has offered me a second home. Without him I could never have known what it is like to be Indian.” Narayan’s fiction earned him comparisons to the work of writers including Anton Chekhov, William Faulkner, O. -

The Ramayana

The Ramayana Inspirations Theater Camp Summer 2016 Script and Songs by Torsti Rovainen Rights held by Rovainen Musicals Story based on the ancient Indian epic of The Ramayana Some spoken lines in Scene IIIB from a translation of The Kurontokai (The Ancient Epic of Love) Script printed on post-consumer recycled paper using less environmentally damaging inks Rovainen Musicals Inspirations Theater Camps and Clubs http://rovainenmusicals.com Scene Synopsis / Song List ACT I (Overture) 0.0: Street scene in modern-day India: Boy playing gets into fight, comforted by Grandmother who sings The Ramayana along with Demon and Human Narrators. Describes creation of world of yakshas and Rakshasas, rakshasas initially peaceful; how Ravana came to be; Rakshasas beginning to prey on humans; the no-man's land between Rakshasa & human territory; Rama & Lakshmana's roles along with Vibishina I Opening Village Bazaar Bazaar Song II Rama learns he to become king in How To Be King Sung by Dasaratha his ministers; overheard by Kaikeyi's servants Manthara and Suchara; Manthara and Suchara discuss the news of Rama's planned kingship. III Sita's rooms; she is arguing with her father about her rejecting suitors. He reflects on how they used to get along in the Lullaby and Then You'd Grow. Maidservants enter for You Should Marry Transitions to brief balcony scene where Rama and Sita see each other and are enamored; brief song (at end of You Should Marry) III.B Having met Sita, Rama is smitten; Lakshamana and the other warriors try to persuade Rama not to marry her, instead to stay single and a warrior in Love Just Makes Things Worse IV Bowlifting ceremony; Rama and Sita decide to marry V Beha Din Ayo Bollywood-inspired short song and dance showing Ayodhya celebrating the upcoming wed- ding VI Manthara and Suchara persuade Kaikeyi to have Rama banished and Bharatha put on throne He Promised You VII Na Jane Rama's Mother, Viswamithra, Sumanthra, nobles, and townsfolk singing to Rama to stay. -

Ramayana: a Divine Drama Actors in the Divine Play As Scripted by Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba

Ramayana: A Divine Drama Actors in the Divine Play as scripted by Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Volume I Compiled by Tumuluru Krishna Murty Edited by Desaraju Sri Sai Lakshmi © Tumuluru Krishna Murty ‘Anasuya’ C-66 Durgabai Deshmukh Colony Ahobil Mutt Road Hyderabad 500007 Ph: +91 (40) 2742 7083/ 8904 Typeset and formatted by: Desaraju Sri Sai Lakshmi Cover Designed by: Insty Print 2B, Ganesh Chandra Avenue Kolkata - 700013 Website: www.instyprint.in VOLUME I No one can shake truth; no one can install untruth. No one can understand My mystery. The best you can do is get immersed in it. The mysterious, indescribable power has come within the reach of all. No one is born and allowed to live for the sake of others. Each has their own burden to carry and lay down. - Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba Put all your burdens on Me. I have come to bear it, so that you can devote yourselves to Sadhana TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR VOLUME I PRAYERS 11 1. SAMARPANAM 17 2. EDITORIAL COMMENTS 27 3. THE ESSENCE OF RAMAYANA 31 4. IKSHVAKU DYNASTY-THE IMPERIAL LINE 81 5. DASARATHA AND HIS CONSORTS 117 118 5.1 DASARATHA 119 5.2 KAUSALYA 197 5.3 SUMITRA 239 5.4 KAIKEYI 261 INDEX 321 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS FIGURE 1: DESCENT OF GANGA 113 FIGURE 2: PUTHRAKAMESHTI YAGA 139 FIGURE 3: RAMA TAKING LEAVE OF DASARATHA 181 FIGURE 4: DASARATHA SEES THE FATALLY INJURED SRAVANA 191 PRAYERS Vaamaankasthitha Jaanaki parilasat kodanda dandaamkare Chakram Chordhva karena bahu yugale samkham saram Dakshine Bibranam Jalajadi patri nayanam Bhadradri muurdhin sthitham Keyuradi vibhushitham Raghupathim Soumitri Yuktham Bhaje!! - Adi Sankara. -

Bala Bhavan Bhajans Contents

Bala Bhavan Bhajans 9252, Miramar Road, San Diego, CA 92126 www.vcscsd.org Bala Bhavan Bhajans Contents GANESHA BHAJANS .................................................................................................. 5 1. Ganesha Sharanam, Sharanam Ganesha ............................................................ 5 2. Gauree Nandana Gajaanana ............................................................................... 5 3. Paahi Paahi Gajaanana Raga: Abheri .......................................... 5 4. Shuklambaradharam ........................................................................................... 5 5. Ganeshwara Gajamukeshwara ........................................................................... 6 6. Gajavadana ......................................................................................................... 6 7. Gajanana ............................................................................................................. 6 8. Ga-yi-yeh Ganapathi Raga: Mohana ........................................ 6 9. Gananatham Gananatham .................................................................................. 7 10. Jaya Ganesha ...................................................................................................... 7 11. Jaya Jaya Girija Bala .......................................................................................... 7 12. Jaya Ganesha ...................................................................................................... 8 13. Sri Maha Ganapathe ..........................................................................................