In Search of a Tropical Gothic in Australian Visual Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher's Notes

Teacher’s Notes These teacher’s notes support the exhibition Cream: Four Decades of Australian Art. They act as a lesson plan, and provide before, during, and after gallery visit suggestions to engage your class with Australian modern art. This resource has been written to align with the draft version Australian Curriculum: The Arts Foundation to Year 10 – 2 July 2013 for Visual Arts as standard reference at the time of production. Used in conjunction with Rockhampton Art Gallery’s Explorer Pack, educators can engage students with concepts of artists, artworks and audience. The questions and activities are designed to encourage practical and critical thinking skills as students respond to artworks in Cream and when making their own representations. The Explorer Pack is free and available upon request to Rockhampton Art Gallery or via the host gallery. This education resource could not exist without the generous support of the Tim Fairfax Family Foundation and Rockhampton Art Gallery thanks the Foundation for their commitment to arts education for regional audiences. Rockhampton Art Gallery would also like to acknowledge the contribution of Education Consultant Deborah Foster. Cream: Four Decades of Australian Art The story of Rockhampton Art Gallery’s modern art collection is a tale of imagination, philanthropy, hard work and cultural pride. Lead by Rex Pilbeam, Mayor of the City of Rockhampton (1952–1982), and supported by regional businesses and local residents, in the mid-1970s the Gallery amassed tens of thousands of dollars in order to develop an art collection. The Australian Contemporary Art Acquisition Program, run by the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council, would match dollar for dollar (later doubled) all monies raised locally. -

Escape Artists Education

ESCAPEartists modernists in the tropics education kit INTRODUC TION & H TEAC ERS NOTES Almost two years in development, Escape Artists: Modernists in the Tropics is the first exhibition by Cairns Regional Gallery to tour nationally. In this exhibition, you and your students will see how the tropical north of Australia has influenced Australia’s greatest artists, some of whom you will be familiar with, others less familiar. The artists featured in the exhibition are: • Harold Abbott • Valerie Albiston • Douglas Annand • Yvonne Atkinson • John Bell • Yvonne Cohen • Ray Crooke • Lawrence Daws • Russell Drysdale • Ian Fairweather • John Firth-smith • Donald Friend • Bruce Goold • Elaine Haxton • Frank Hinder • Frank Hodginson • Sydney Nolan • Alan Oldfield • Margaret Olley • John Olsen • Tony Tuckson • Brett Whitely • Fred Williams • Noel Wood The lure of an exotic, untouched, tropical paradise has a tradition in modern art beginning with Gaugin in Tahiti. It was this desire to discover and explore new worlds which attracted these artists to the Far North - a part of Australia like no other they had seen. Here they found a region of extraordinary, abundant natural beauty and a cultural pot pourri of indigenous inhabitants and people from all over the world. This exciting mixture of important artworks was assembled from major private and public collections by Gavin Wilson,curator of the successful Artists of Hill End exhibition at The Art Gallery of News South Wales. Escape Artists provides a significant look at the cultural and historic heritage of North Queensland and the rest of northern Australia. You and your students will find some pleasant surprises among the works in the exhibition. -

Danks News Final

Artworks where Resale Royalty is not applicable Artworks under $1,000 and so exempt from Resale Royalty Collectible Australian artists in this category include: consider works on paper including prints, smaller works, works by less mainstream or emerging artists, decorative arts Robert Clinch 1957 - Black and White 2008 suite of eight lithographs 19 x 20.5 cm each, edition of 40 These lithographs are available individually or in matching numbered sets. Troy Pieta Alice Ali Trudy Raggett Kemarr 1980 - Arrkerr 2007 synthetic polymer on carved wood height: 40 cm David and Goliath Empire Trudy Raggett Kemarr 1980 - Arrkerr 2007 synthetic polymer on carved wood height: 40 cm Richard III Alien Artworks where Resale Royalty is not applicable Deceased Artists who have been deceased for more than 70 years Collectible Australian artists in this category include: Clarice Beckett, Merric Boyd, Penleigh Boyd, Henry Burn, Abram Louis Buvelot, Nicholas Chevalier, Charles Conder, David Davies, John Glover, William Buelow Gould, Elioth Gruner, Haughton Forrest, Emmanuel Phillips Fox, A.H. Fullwood, Henry Gritten, Bernard Hall, J.J. Hilder, Tom Humphrey, Bertram Mackennal, John Mather, Frederick McCubbin, G.P. Nerli, W.C. Piguenit, John Skinner Prout, Hugh Ramsay, Charles Douglas Richardson, Tom Roberts, John Peter Russell, J.A. Turner, William Strutt, Eugene Von Guerard, Isaac Whitehead, Walter Withers Bernard Hall 1859 - 1935 Model with Globe oil on canvas 67x 49 cm William Buelow Gould 1803 - 1853 Still Life of Flowers c.1850 oil on canvas 41 x 50 cm -

European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960

INTERSECTING CULTURES European Influences in the Fine Arts: Melbourne 1940-1960 Sheridan Palmer Bull Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree ofDoctor ofPhilosophy December 2004 School of Art History, Cinema, Classics and Archaeology and The Australian Centre The University ofMelbourne Produced on acid-free paper. Abstract The development of modern European scholarship and art, more marked.in Austria and Germany, had produced by the early part of the twentieth century challenging innovations in art and the principles of art historical scholarship. Art history, in its quest to explicate the connections between art and mind, time and place, became a discipline that combined or connected various fields of enquiry to other historical moments. Hitler's accession to power in 1933 resulted in a major diaspora of Europeans, mostly German Jews, and one of the most critical dispersions of intellectuals ever recorded. Their relocation to many western countries, including Australia, resulted in major intellectual and cultural developments within those societies. By investigating selected case studies, this research illuminates the important contributions made by these individuals to the academic and cultural studies in Melbourne. Dr Ursula Hoff, a German art scholar, exiled from Hamburg, arrived in Melbourne via London in December 1939. After a brief period as a secretary at the Women's College at the University of Melbourne, she became the first qualified art historian to work within an Australian state gallery as well as one of the foundation lecturers at the School of Fine Arts at the University of Melbourne. While her legacy at the National Gallery of Victoria rests mostly on an internationally recognised Department of Prints and Drawings, her concern and dedication extended to the Gallery as a whole. -

Annual Report 2011–12 Annual Report 2011–12 the National Gallery of Australia Is a Commonwealth (Cover) Authority Established Under the National Gallery Act 1975

ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. Henri Matisse Oceania, the sea (Océanie, la mer) 1946 The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the screenprint on linen cultural enrichment of all Australians through access 172 x 385.4 cm to their national art gallery, the quality of the national National Gallery of Australia, Canberra collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and gift of Tim Fairfax AM, 2012 programs, and the professionalism of our staff. The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, corporate governance, administration and financial and business management. In 2011–12, the National Gallery of Australia received an appropriation from the Australian Government totalling $48.828 million (including an equity injection of $16.219 million for development of the national collection), raised $13.811 million, and employed 250 full-time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2012 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Produced by the Publishing Department of the National Gallery of Australia Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Susannah Luddy Printed by New Millennium National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au/AboutUs/Reports 30 September 2012 The Hon Simon Crean MP Minister for the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister On behalf of the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, I have pleasure in submitting to you, for presentation to each House of Parliament, the National Gallery of Australia’s Annual Report covering the period 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. -

Art and Artists in Perth 1950-2000

ART AND ARTISTS IN PERTH 1950-2000 MARIA E. BROWN, M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Design Art History 2018 THESIS DECLARATION I, Maria Encarnacion Brown, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in the degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. No part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. The work(s) are not in any way a violation or infringement of any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. The research involving human data reported in this thesis was assessed and approved by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval # RA/4/1/7748. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature: Date: 14 May 2018 i ABSTRACT This thesis provides an account of the development of the visual arts in Perth from 1950 to 2000 by examining in detail the state of the local art scene at five key points in time, namely 1953, 1962, 1975, 1987 and 1997. -

PRIMARY Education Resource

A break away! painted at Corowa, New South Wales, and Melbourne, 1891 oil on canvas 137.3 x 167.8 cm Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, Elder Bequest Fund, 1899 PRIMARY Education resource Primary Education Resource 1 For teachers How to use this learning resource for primary students Tom Roberts is a major INTRODUCTION exhibition of works from the National Gallery of Australia’s ‘All Australian paintings are in some way a homage to Tom Roberts.’ Arthur Boyd collection as well as private and Tom Roberts (1856–1931) is arguably one of Australia’s public collections from around best-known and most loved artists, standing high among his talented associates at a vital moment in local painting. Australia. His output was broad-ranging, and includes landscapes, figures in the landscape, industrial landscapes and This extraordinary exhibition brings together Roberts’ cityscapes. He was also Australia’s leading portrait most famous paintings loved by all Australians. Paintings painter of the late nineteenth and early twentieth such as Shearing the rams 1888–90 and A break away! centuries. In addition he made a small number of etchings 1891 are among the nation’s best-known works of art. and sculptures and in his later years he painted a few nudes and still lifes. This primary school resource for the Tom Roberts exhibition explores the themes of the 9 by 5 Impression Roberts was born in Dorchester, Dorset, in the south of exhibition, Australia and the landscape, Portraiture, England and spent his first 12 years there. However he Making a nation, and Working abroad. -

Ocean to Outback: Australian Landscape Painting 1850–1950

travelling exhibition Ocean to Outback: Australian landscape painting 1850–1950 4 August 2007 – 3 May 2009 … it is continually exciting, these curious and strange rhythms which one discovers in a vast landscape, the juxtaposition of figures, of objects, all these things are exciting. Add to that again the peculiarity of the particular land in which we live here, and you get a quality of strangeness that you do not find, I think, anywhere else. Russell Drysdale, 19601 From the white heat of our beaches to the red heart of 127 of the 220 convicts on board died.2 Survivors’ accounts central Australia, Ocean to Outback: Australian landscape said the ship’s crew fired their weapons at convicts who, in painting 1850–1950 conveys the great beauty and diversity a state of panic, attempted to break from their confines as of the Australian continent. Curated by the National Gallery’s the vessel went down. Director Ron Radford, this major travelling exhibition is The painting is dominated by a huge sky, with the a celebration of the Gallery’s twenty-fifth anniversary. It broken George the Third dwarfed by the expanse. Waves features treasured Australian landscape paintings from the crash over the decks of the ship while a few figures in the national collection and will travel to venues throughout each foreground attempt to salvage cargo and supplies. This is Australian state and territory until 2009. a seascape that evokes trepidation and anxiety. The small Encompassing colonial through to modernist works, the figures contribute to the feeling of human vulnerability exhibition spans the great century of Australian landscape when challenged by the extremities of nature. -

2014–15 Annual Report

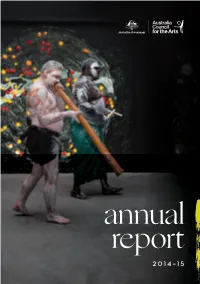

annual report 2 0 1 4 – 1 5 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Minister for the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 26 August 2015 Dear Minister, On behalf of the Board of the Australia Council, I am pleased to submit the Australia Council Annual Report for 2014–15. The Board is responsible for the preparation and content of the annual report pursuant to section 46 of the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013, the Commonwealth Authorities (Annual Reporting) Order 2011 and the Australia Council Act 2013. The following report of operations and financial statements were adopted by resolutions of the Board on the 26 August 2015. Yours faithfully, Rupert Myer AO Chair, Australia Council CONTENTS Our purpose 3 Report from the Chair 4 Report from the CEO 8 Section 1: Agency Overview 12 About the Australia Council 15 2014–15 at a glance 17 Structure of the Australia Council 18 Organisational structure 19 Funding overview 21 New grants model 28 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts 32 Supporting Arts Organisations 34 Major Performing Arts Companies 36 Key Organisations and Territory Orchestras 38 Achieving a culturally ambitious nation 41 Government initiatives 60 Arts Research 64 Section 2: Report on Performance Outcomes 66 Section 3: Management and Accountability 72 The Australia Council Board 74 Committees 81 Management of Human Resources 90 Ecologically sustainable development 93 Executive Team at 30 June 2015 94 Section 4: Financial Statements 96 Compliance index 148 Cover: Matthew Doyle and Djakapurra Munyarryun at the opening of the Australian Pavilion in Venice. Image credit: Angus Mordant Unicycle adagio with Kylie Raferty and April Dawson, 2014, Cirus Oz. -

Smith & Singer Lead the Market Following

Melbourne | +61 (0)3 9508 9900 | Thomas Austin | [email protected] SMITH & SINGER LEAD THE MARKET FOLLOWING SEPTEMBER AUCTION TOTAL OF $6,304,375, WITH 149% SOLD BY VALUE AND 87% BY VOLUME Smith & Singer (Formerly Trading as Sotheby’s Australia) Achieves the Highest Sold Rates at the Company in More than a Decade Whiteley Masterpiece ‘White Corella’ 1987 Leads Auction with $750,000 Monumental Shoalhaven Canvas by Arthur Boyd Realises $550,000 Auction Records for Elioth Gruner & Russell Drysdale (Work on Paper) BRETT WHITELEY 1939-1992 White Corella 1987 oil on canvas, 106.3 x 91.1 cm frame: original, Brett Lichtenstein, Sydney Estimate $600,000–800,000 Sold for $750,000 © Wendy Whiteley SYDNEY, 3 September 2020 – Bidders from across Australia and the around the globe vied for the works of art on offer at Smith & Singer’s auction of Important Australian & International Art last night. Clients in the Sydney saleroom competed against those watching the auction online and speaking via telephones, resulting in an outstanding sold rate of 149.43% by value and 87% by volume – the highest in more than a decade at Smith & Singer (formerly trading as Sotheby’s Australia). Totalling $6,304,375, the auction far exceeded the pre-sale low estimate with strong results for leading Australian traditional, modern and contemporary artists – including Arthur Boyd, Rupert Bunny, Ethel Carrick, Elioth Gruner, Melbourne | +61 (0)3 9508 9900 | Thomas Austin | [email protected] Akio Makigawa, Frederick McCubbin, William Robinson, Arthur Streeton, and Brett Whiteley, amongst others. The evening sale commenced with a delicate duo of Arthur Boyd Shoalhaven small-scale oils on board, which sold for $53,750 and $52,500 respectively, both exceeding their pre-sale $40,000 high estimates. -

Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada

Sydney College of the Arts The University of Sydney Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Thesis Towards an Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada Rolande Souliere A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Rolande Souliere i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lynette Riley for her assistance in the final process of writing this thesis. I would also like to thank and acknowledge Professor Valerie Harwood and Dr. Tom Loveday. Photographer Peter Endersbee (1949-2016) is most appreciated for the photographic documentation over my visual arts career. Many people have supported me during the research, the writing and thesis preparation. First, I would like to thank Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney for providing me with this wonderful opportunity, and Michipicoten First Nation, Canada, especially Linda Petersen, for their support and encouragement over the years. I would like to thank my family - children Chloe, Sam and Rohan, my sister Rita, and Kristi Arnold. A special thank you to my beloved mother Carolyn Souliere (deceased) for encouraging me to enrol in a visual arts degree. I dedicate this paper to her. -

Important Australian Art Auction in Sydney 16 August 2017

Press Release For Immediate Release Melbourne 10 August 2017 John Keats 03 9508 9900 | 0412 132 520 [email protected] Important Australian Art Auction in Sydney 16 August 2017 ARTHUR BOYD 1920-1999 Moby Dick Hill (1949). Estimate $1,000,000-1,200,000 Million dollar masterpiece by Angry Penguins artist Arthur Boyd National identity defined in paintings by Russell Drysdale Jeffrey Smart’s rare and unique record of 20th century Australian modernism & industrialisation One of the most significant images from Charles Blackman ‘Schoolgirl’ series Important visual & literary records of Australian Colonisation by Thomas John Domville Taylor Strong buyer interest is anticipated at Sotheby’s Australia’s August sale of Important Australian Art on 16 August at the InterContinental Sydney. With 97 works of art for auction estimated at $9.02 million to $11.77 million, the sale presents a collection of extraordinary moments in Australian art history. Surveying major stylistic developments, the auction offers rare and prestigious examples of Colonial Art, Naturalism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Modernism, and Abstraction, along with ground-breaking paintings and works on paper by the most influential artistic innovators of historical, modern and contemporary Australian art. 1 | Sotheby’s Australia is a trade mark used under licence from Sotheby's. Second East Auction Holdings Pty Ltd is independent of the Sotheby's Group. The Sotheby's Group is not responsible for the acts or omissions of Second East Auction Holdings Pty Ltd