LEARNING RESOURCE How to Use This Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-Making

Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Contemporary Asian Art and Exhibitions Connectivities and World-making Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner ASIAN STUDIES SERIES MONOGRAPH 6 Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Antoinette, Michelle, author. Title: Contemporary Asian art and exhibitions : connectivities and world-making / Michelle Antoinette and Caroline Turner. ISBN: 9781925021998 (paperback) 9781925022001 (ebook) Subjects: Art, Asian. Art, Modern--21st century. Intercultural communication in art. Exhibitions. Other Authors/Contributors: Turner, Caroline, 1947- author. Dewey Number: 709.5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover illustration: N.S. Harsha, Ambitions and Dreams 2005; cloth pasted on rock, size of each shadow 6 m. Community project designed for TVS School, Tumkur, India. © N.S. Harsha; image courtesy of the artist; photograph: Sachidananda K.J. Cover design and layout by ANU Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2014 ANU Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii Introduction Part 1 — Critical Themes, Geopolitical Change and Global Contexts in Contemporary Asian Art . 1 Caroline Turner Introduction Part 2 — Asia Present and Resonant: Themes of Connectivity and World-making in Contemporary Asian Art . 23 Michelle Antoinette 1 . Polytropic Philippine: Intimating the World in Pieces . 47 Patrick D. Flores 2 . The Worlding of the Asian Modern . -

Annual Report 2011–12 Annual Report 2011–12 the National Gallery of Australia Is a Commonwealth (Cover) Authority Established Under the National Gallery Act 1975

ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. Henri Matisse Oceania, the sea (Océanie, la mer) 1946 The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the screenprint on linen cultural enrichment of all Australians through access 172 x 385.4 cm to their national art gallery, the quality of the national National Gallery of Australia, Canberra collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and gift of Tim Fairfax AM, 2012 programs, and the professionalism of our staff. The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, corporate governance, administration and financial and business management. In 2011–12, the National Gallery of Australia received an appropriation from the Australian Government totalling $48.828 million (including an equity injection of $16.219 million for development of the national collection), raised $13.811 million, and employed 250 full-time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2012 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Produced by the Publishing Department of the National Gallery of Australia Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Susannah Luddy Printed by New Millennium National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au/AboutUs/Reports 30 September 2012 The Hon Simon Crean MP Minister for the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister On behalf of the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, I have pleasure in submitting to you, for presentation to each House of Parliament, the National Gallery of Australia’s Annual Report covering the period 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. -

Imants Tillers

IMANTS TILLERS Born Sydney, Australia 1950. EDUCATION 2005 Awarded a Doctor of Letters (Honoris Causa), University of New South Wales, Sydney. 2001 Visiting Fellow, Fine Art Research Centre, Southampton Institute, UK Co-curator with Marketta Seppälä, Empathy: Beyond the Horizon, Pori Art Museum, Finland. Appointed Trustee of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. 1976 Cité Internationale des Arts Residency, Paris Owen Tooth Cottage Residency, Vence. 1969 – 72 Bachelor of Science Architecture (First Class Hons, University Medal), University of Sydney. 2010 Collaborated with Janis Balodis on Exile and Fatherland, 53rd Australian Latvian Arts Festival, Melbourne 2011 Appointed a Director of Immigration Place, Australia, Canberra. SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2016 Metafisca Australe, ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne. 2015 Metafisca Australe, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney 2014 Big Storm Between Two Place: Michael Nelson Jagamara and Imants Tillers, Fire works Gallery, Brisbane Latvian Mandala, Australian Latvian Arts Festival, Latvian House, Sydney. Haunted Nation, Bett Gallery, Hobart The Philosopher’s Walk, Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide 2013 The Fleeting Self, ARC ONE Gallery, Melbourne 2012 Tabula Rasa, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney The Loaded Ground: Michael Nelson Jagamara and Imants Tillers, Drill Hall Gallery, Australian National University Art Gallery, Canberra. 2011 Nature Speaks, Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide. The Journey South, Bett Gallery, Hobart. 2010 The Blossoming World, Arc One Gallery. A Poem of the Land, Roslyn Oxley9 Gallery, Sydney. Dual Worlds: Dadang Christanto and Imants Tillers, Jan Manton Art, Brisbane. 2009 Leap of Faith, Greenaway Art Gallery, Adelaide. Value Added Landscapes, Jan Manton Art, Brisbane. Clouds on a distant horizon, Bett Gallery, Hobart. The Long Poem, Lawrence Wilson Art Gallery, University of Western Australia, Perth. -

Art and Artists in Perth 1950-2000

ART AND ARTISTS IN PERTH 1950-2000 MARIA E. BROWN, M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Design Art History 2018 THESIS DECLARATION I, Maria Encarnacion Brown, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in the degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. No part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. The work(s) are not in any way a violation or infringement of any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. The research involving human data reported in this thesis was assessed and approved by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval # RA/4/1/7748. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature: Date: 14 May 2018 i ABSTRACT This thesis provides an account of the development of the visual arts in Perth from 1950 to 2000 by examining in detail the state of the local art scene at five key points in time, namely 1953, 1962, 1975, 1987 and 1997. -

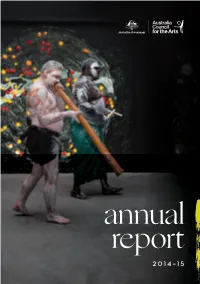

2014–15 Annual Report

annual report 2 0 1 4 – 1 5 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Minister for the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 26 August 2015 Dear Minister, On behalf of the Board of the Australia Council, I am pleased to submit the Australia Council Annual Report for 2014–15. The Board is responsible for the preparation and content of the annual report pursuant to section 46 of the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013, the Commonwealth Authorities (Annual Reporting) Order 2011 and the Australia Council Act 2013. The following report of operations and financial statements were adopted by resolutions of the Board on the 26 August 2015. Yours faithfully, Rupert Myer AO Chair, Australia Council CONTENTS Our purpose 3 Report from the Chair 4 Report from the CEO 8 Section 1: Agency Overview 12 About the Australia Council 15 2014–15 at a glance 17 Structure of the Australia Council 18 Organisational structure 19 Funding overview 21 New grants model 28 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts 32 Supporting Arts Organisations 34 Major Performing Arts Companies 36 Key Organisations and Territory Orchestras 38 Achieving a culturally ambitious nation 41 Government initiatives 60 Arts Research 64 Section 2: Report on Performance Outcomes 66 Section 3: Management and Accountability 72 The Australia Council Board 74 Committees 81 Management of Human Resources 90 Ecologically sustainable development 93 Executive Team at 30 June 2015 94 Section 4: Financial Statements 96 Compliance index 148 Cover: Matthew Doyle and Djakapurra Munyarryun at the opening of the Australian Pavilion in Venice. Image credit: Angus Mordant Unicycle adagio with Kylie Raferty and April Dawson, 2014, Cirus Oz. -

Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada

Sydney College of the Arts The University of Sydney Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Thesis Towards an Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada Rolande Souliere A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Rolande Souliere i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lynette Riley for her assistance in the final process of writing this thesis. I would also like to thank and acknowledge Professor Valerie Harwood and Dr. Tom Loveday. Photographer Peter Endersbee (1949-2016) is most appreciated for the photographic documentation over my visual arts career. Many people have supported me during the research, the writing and thesis preparation. First, I would like to thank Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney for providing me with this wonderful opportunity, and Michipicoten First Nation, Canada, especially Linda Petersen, for their support and encouragement over the years. I would like to thank my family - children Chloe, Sam and Rohan, my sister Rita, and Kristi Arnold. A special thank you to my beloved mother Carolyn Souliere (deceased) for encouraging me to enrol in a visual arts degree. I dedicate this paper to her. -

AH374 Australian Art and Architecture

AH374 Australian Art and Architecture The search for beauty, meaning and freedom in a harsh climate Boston University Sydney Centre Spring Semester 2015 Course Co-ordinator Peter Barnes [email protected] 0407 883 332 Course Description The course provides an introduction to the history of art and architectural practice in Australia. Australia is home to the world’s oldest continuing art tradition (indigenous Australian art) and one of the youngest national art traditions (encompassing Colonial art, modern art and the art of today). This rich and diverse history is full of fascinating characters and hard won aesthetic achievements. The lecture series is structured to introduce a number of key artists and their work, to place them in a historical context and to consider a range of themes (landscape, urbanism, abstraction, the noble savage, modernism, etc.) and issues (gender, power, freedom, identity, sexuality, autonomy, place etc.) prompted by the work. Course Format The course combines in-class lectures employing a variety of media with group discussions and a number of field trips. The aim is to provide students with a general understanding of a series of major achievements in Australian art and its social and geographic context. Students should also gain the skills and confidence to observe, describe and discuss works of art. Course Outline Week 1 Session 1 Introduction to Course Introduction to Topic a. Artists – The Port Jackson Painter, Joseph Lycett, Tommy McCrae, John Glover, Augustus Earle, Sydney Parkinson, Conrad Martens b. Readings – both readers are important short texts. It is compulsory to read them. They will be discussed in class and you will need to be prepared to contribute your thoughts and opinions. -

DANIE MELLOR Curriculum Vitae Born Mackay, Queensland 1971

DANIE MELLOR Curriculum Vitae Born Mackay, Queensland 1971 EMPLOYMENT/APPOINTMENTS Artist 2010 – 2014 Senior Lecturer, Theoretical Enquiry, Sydney College of the Arts, the University of Sydney 2014 Chair of Artform (Visual Arts), Australia Council for the Arts 2013 - 2014 Chair, Sector Strategy Panel, Visual Arts, Australia Council for the Arts 2013 Chair, Visual Art Board and Governing Council member, Australia Council for the Arts 2010 – 2013 Visual Arts Board, Australia Council for the Arts 2008 – 2010 Subject Chair, Theoretical Enquiry, Sydney College of the Arts, the University of Sydney 2005 – 2010 Lecturer, Theories of Art Practice/Theoretical Enquiry, Sydney College of the Arts, the University of Sydney 1996 – 2004 Visual arts teacher, Orana School, Canberra Sessional lecturer, Graphic Investigation Workshop and Printmedia and Drawing Workshop, School of Art, National Institute of the Arts, The Australian National University EDUCATION Certificate in Art, North Adelaide School of Art, SA Bachelor of Arts (Visual) With Honours, Canberra School of Art, ANU MA (Fine Art), Birmingham Institute of Art and Design, University of Central England, UK PhD, School of Art, National Institute of the Arts, ANU AWARDS Winner, Adelaide Perry Prize for DraWing, PLC Croydon, NSW, 2010 | Winner, 26th National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art Awards, Museum and Gallery of the Northern Territory, 2009 | Winner, 2009 Indigenous Ceramics AWard, Shepparton Art Gallery | Winner, 2008 Tallis Foundation National Works on Paper, Mornington Peninsula -

View Article

Rover Thomas leats 29, 301 and Paddy JaminJi (cat.28) initiated a renewal of painting in the Eastern Kimberley by lifting the lid on the secret histories of Australia with paintings of country drenched with the blood of Aboriginal victims of massacres; in 1990, with Trevor Nickolls, Rover Thomas was the first Aboriginal artist to appear at the Venice Biennale. Djambawa Marawili leat.81 and John Mawurndjul leats 3, 6, 71. two of the most renowned contemporary Australian artists with a string of international contemporary art appearances to their names, have revolutionised bark painting to make us feel the hum of ancestral powers in the earth itself. And that is not even to mention Albert Namatjira, who beguiled a generation but whose life ended in tragedy. The strong photographic and video component in the last part of the selection reflects the burgeoning of these media around the globe. Tracey Moffatt, one of the most internationally acclaimed contemporary Australian artists, came to prominence in the 1990s with her vibrant, quasi-narrative series of photographs [fig.71, and her film and video compilations looking at gender, popular culture, racial politics and stereotypes leat.1911. Simryn Gill, representing Australia at the 55th Venice Biennale in 2013, considers questions of place and history in her work leat. 1881. The displacement of objects in her photographs echoes our modern-day journeys and migrations. The Australian population, now 23 million, has more than quadrupled in size since 1918, much of that increase from immigration. Since 1945 more than Fig. 8 CHRISTIAN THOMPSON, Black 7million people have settled in the country as new Gum 1, from the series Australian immigrants, including more than 800,000 refugees. -

Imants Tillers: One World Many Visions, Introduces Teachers and National Gallery of Australia Secondary Students to the Work of This Signifi Cant Australian Artist

National Gallery of Australia, Canberra 14 July – 16 October 2006 This education material, produced to accompany the exhibition GALLERY INFORMATION Imants Tillers: one world many visions, introduces teachers and National Gallery of Australia secondary students to the work of this signifi cant Australian artist. Parkes Place Canberra ACT This major exhibition traces the development of contemporary artist nga.gov.au Imants Tillers from 1984 to 2006. The title of the exhibition, Imants OPENING HOURS Tillers: one world many visions, suggests the multiple nature of the Open daily 10 am – 5 pm (except Christmas Day) references in Tillers’ art that in turn refl ect the diversity of the world in which we live. ADMISSION Entry to the permanent collection is free Individual cards introduce and discuss an image, and present Entry to paying exhibitions is free for booked school groups discussion points and activities. The diverse subject matter Entry to all exhibitions is free for 16s and under explored within the exhibition links to key learning areas, such as Art, English, History, Mathematics, Science and Philosophy. EDUCATION GROUP BOOKINGS AND ENQUIRIES phone 02 6240 6519 (Monday to Friday) This kit has been designed to be used in conjunction with a visit fax 02 6240 6560 to the exhibition at the National Gallery of Australia. Additional email [email protected] material is available on the Gallery’s website: nga.gov.au/Tillers. web nga.gov.au/Tours SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY GALLERY CAFE Deborah Hart (ed.), Imants Tillers: one world many visions, 10 am – 4.30 pm daily exhibition catalogue, Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2006. -

Beyond the Aesthetic a STUDY OF

Beyond the Aesthetic A STUDY OF INDIGENEITY AND NARRATIVE IN CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN ART – VOLUME ONE – Catherine Slocum December 2016 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University © Copyright by Catherine Slocum 2016 All Rights Reserved INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS SHOULD BE AWARE THAT THIS DOCUMENT CONTAINS NAMES AND IMAGES OF DECEASED PERSONS. ii THE TERM ‘INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIANS’ HAS BEEN ADOPTED AND MAINTAINED THROUGHOUT THIS THESIS. THERE ARE MANY DIFFERENT DISPLAYS OF THIS TERM, HOWEVER THIS TERM IS USED AS IT INCLUDES THOSE WHO IDENTIFY AS ABORIGINAL, TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER AND ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER. iii DECLARATION I declare that this thesis is wholly my own original work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. ………………………………………… Catherine Slocum December 2016 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Professor Paul Pickering for the continuous support of my PhD study and research. His insightful comments and valuable discussion are gratefully acknowledged. My sincere thanks are extended to Dr Thuy Do for her useful comments in the final stages and Dr Lan Tran for her valuable assistance during the course of my study. A very special thanks to Vernon Ah Kee, Tony Albert, Brook Andrew, Daniel Boyd, Dianne Jones, Christopher Pease and Christian Thompson whose work I feel privileged to have been given the opportunity to study at length. The project would not have been possible without the specialist Indigenous Australian collection at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) Library in Canberra. I gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the College of Arts and Social Sciences at the Australian National University. -

Aboriginal Art in NSW

Pay Attention: Aboriginal Art in NSW Priya Vaughan A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The Australian National University December 2017 This work is the result of original research carried out by the author except where otherwise indicated in the text. Priya Vaughan Research School of Humanities and the Arts The Australian National University Supervisory Panel: Professor Howard Morphy (Chair) Dr Maria Nugent Dr John Carty i Note to Readers Readers are advised that this text may contain names and images of deceased persons. Please note the spellings of Aboriginal language, cultural and nations names vary across this thesis. I have used the preferred spellings of participants when discussing their ideas, work and experiences. iii Thanks and Acknowledgements The road to PhD submission is long, and often laborious, however, in looking back on researching this work I feel a kind of disbelieving delight that so much of the process was fascinating, inspiring and fun. Much of this is due to the artists, curators, arts workers, and educators who participated in the creation of this work. Their kindness, interest and ideas, often embodied and represented in the art they made, told me everything I now know about Aboriginal art in NSW, and taught me a whole lot else besides. I would like to express my profound thanks to these participants. Simply put, without your generosity, there would be no thesis. Thank you for welcoming me to your Country; for having me in your homes and work places; sharing your ideas, feelings and experiences; reviewing transcripts and reading drafts; helping me when I got things wrong, and for your kind words when I got things right.