Aboriginal Art in NSW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Aboriginal Art

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The University of Sydney: Sydney eScholarship Journals online Australian Aboriginal Art Patrick Hutchings To attack one’s neighbours, to pass or to crush and subdue more remote peoples without provocation and solely for the thirst for dominion—what is one to call it but brigandage on a grand scale?1 The City of God, St Augustine of Hippo, IV Ch 6 ‘The natives are extremely fond of painting and often sit hours by me when at work’ 2 Thomas Watling The Australians and the British began their relationship by ‘dancing together’, so writes Inge Clendinnen in her multi-voiced Dancing With Strangers 3 which weaves contemporary narratives of Sydney Cove in 1788. The event of dancing is witnessed to by a watercolour by Lieutenant William Bradley, ‘View in Broken Bay New South Wales March 1788’, which is reproduced by Clendinnen as both a plate and a dustcover.4 By ‘The Australians’ Clendinnen means the Aboriginal pop- ulation. But, of course, Aboriginality is not an Aboriginal concept but an Imperial one. As Sonja Kurtzer writes: ‘The concept of Aboriginality did not even exist before the coming of the European’.5 And as for the terra nullius to which the British came, it was always a legal fiction. All this taken in, one sees why Clendinnen calls the First People ‘The Australians’, leaving most of those with the current passport very much Second People. But: winner has taken, almost, all. The Eddie Mabo case6 exploded terra nullius, but most of the ‘nobody’s land’ now still belongs to the Second People. -

STUDY GUIDE by Marguerite O’Hara, Jonathan Jones and Amanda Peacock

A personal journey into the world of Aboriginal art A STUDY GUIDE by MArguerite o’hArA, jonAthAn jones And amandA PeAcock http://www.metromagazine.com.au http://www.theeducationshop.com.au ‘Art for me is a way for our people to share stories and allow a wider community to understand our history and us as a people.’ SCREEN EDUCATION – Hetti Perkins Front cover: (top) Detail From GinGer riley munDuwalawala, Ngak Ngak aNd the RuiNed City, 1998, synthetic polyer paint on canvas, 193 x 249.3cm, art Gallery oF new south wales. © GinGer riley munDuwalawala, courtesy alcaston Gallery; (Bottom) Kintore ranGe, 2009, warwicK thornton; (inset) hetti perKins, 2010, susie haGon this paGe: (top) Detail From naata nunGurrayi, uNtitled, 1999, synthetic polymer paint on canvas, 2 122 x 151 cm, mollie GowinG acquisition FunD For contemporary aBoriGinal art 2000, art Gallery oF new south wales. © naata nunGurrayi, aBoriGinal artists aGency ltD; (centre) nGutjul, 2009, hiBiscus Films; (Bottom) ivy pareroultja, rrutjumpa (mt sonDer), 2009, hiBiscus Films Introduction GulumBu yunupinGu, yirrKala, 2009, hiBiscus Films DVD anD WEbsitE short films – five for each of the three episodes – have been art + soul is a groundbreaking three-part television series produced. These webisodes, which explore a selection of exploring the range and diversity of Aboriginal and Torres the artists and their work in more detail, will be available on Strait Islander art and culture. Written and presented by the art + soul website <http://www.abc.net.au/arts/art Hetti Perkins, senior curator of Aboriginal and Torres Strait andsoul>. Islander art at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, and directed by Warwick Thornton, award-winning director of art + soul is an absolutely compelling series. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UM l films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UME a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, b^inning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back o f the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy, ffigher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UM l directly to order. UMl A Bell & Howell Infoimation Company 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor MI 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Velar-Initial Etyma and Issues in Comparative Pama-Nyungan by Susan Ann Fitzgerald B.A.. University of V ictoria. 1989 VI.A. -

Becoming Art: Some Relationships Between Pacific Art and Western Culture Susan Cochrane University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 1995 Becoming art: some relationships between Pacific art and Western culture Susan Cochrane University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Cochrane, Susan, Becoming art: some relationships between Pacific ra t and Western culture, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, , University of Wollongong, 1995. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/2088 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. BECOMING ART: SOME RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN PACIFIC ART AND WESTERN CULTURE by Susan Cochrane, B.A. [Macquarie], M.A.(Hons.) [Wollongong] 203 CHAPTER 4: 'REGIMES OF VALUE'1 Bokken ngarribimbun dorlobbo: ngarrikarrme gunwok kunmurrngrayek ngadberre ngarribimbun dja mak kunwarrde kne ngarribimbun. (There are two reasons why we do our art: the first is to maintain our culture, the second is to earn money). Injalak Arts and Crafts Corporate Plan INTRODUCTION In the last chapter, the example of bark paintings was used to test Western categories for indigenous art. Reference was also made to Aboriginal systems of classification, in particular the ways Yolngu people classify painting, including bark painting. Morphy's concept, that Aboriginal art exists in two 'frames', was briefly introduced, and his view was cited that Yolngu artists increasingly operate within both 'frames', the Aboriginal frame and the European frame (Morphy 1991:26). This chapter develops the theme of how indigenous art objects are valued, both within the creator society and when they enter the Western art-culture system. When aesthetic objects move between cultures the values attached to them may change. -

![AR Radcliffe-Brown]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4080/ar-radcliffe-brown-684080.webp)

AR Radcliffe-Brown]

P129: The Personal Archives of Alfred Reginald RADCLIFFE-BROWN (1881- 1955), Professor of Anthropology 1926 – 1931 Contents Date Range: 1915-1951 Shelf Metre: 0.16 Accession: Series 2: Gift and deposit register p162 Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown was born on 17 January 1881 at Aston, Warwickshire, England, second son of Alfred Brown, manufacturer's clerk and his wife Hannah, nee Radcliffe. He was educated at King Edward's School, Birmingham, and Trinity College, Cambridge (B.A. 1905, M. A. 1909), graduating with first class honours in the moral sciences tripos. He studied psychology under W. H. R. Rivers, who, with A. C. Haddon, led him towards social anthropology. Elected Anthony Wilkin student in ethnology in 1906 (and 1909), he spent two years in the field in the Andaman Islands. A fellow of Trinity (1908 - 1914), he lectured twice a week on ethnology at the London School of Economics and visited Paris where he met Emily Durkheim. At Cambridge on 19 April 1910 he married Winifred Marie Lyon; they were divorced in 1938. Radcliffe-Brown (then known as AR Brown) joined E. L. Grant Watson and Daisy Bates in an expedition to the North-West of Western Australia studying the remnants of Aboriginal tribes for some two years from 1910, but friction developed between Brown and Mrs. Bates. Brown published his research from that time in an article titled “Three Tribes of Western Australia”, The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 43, (Jan. - Jun., 1913), pp. 143-194. At the 1914 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in Melbourne, Daisy Bates accused Brown of gross plagiarism. -

Annual Report 2011–12 Annual Report 2011–12 the National Gallery of Australia Is a Commonwealth (Cover) Authority Established Under the National Gallery Act 1975

ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 ANNUAL REPORT 2011–12 The National Gallery of Australia is a Commonwealth (cover) authority established under the National Gallery Act 1975. Henri Matisse Oceania, the sea (Océanie, la mer) 1946 The vision of the National Gallery of Australia is the screenprint on linen cultural enrichment of all Australians through access 172 x 385.4 cm to their national art gallery, the quality of the national National Gallery of Australia, Canberra collection, the exceptional displays, exhibitions and gift of Tim Fairfax AM, 2012 programs, and the professionalism of our staff. The Gallery’s governing body, the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, has expertise in arts administration, corporate governance, administration and financial and business management. In 2011–12, the National Gallery of Australia received an appropriation from the Australian Government totalling $48.828 million (including an equity injection of $16.219 million for development of the national collection), raised $13.811 million, and employed 250 full-time equivalent staff. © National Gallery of Australia 2012 ISSN 1323 5192 All rights reserved. No part of this publication can be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Produced by the Publishing Department of the National Gallery of Australia Edited by Eric Meredith Designed by Susannah Luddy Printed by New Millennium National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au/AboutUs/Reports 30 September 2012 The Hon Simon Crean MP Minister for the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister On behalf of the Council of the National Gallery of Australia, I have pleasure in submitting to you, for presentation to each House of Parliament, the National Gallery of Australia’s Annual Report covering the period 1 July 2011 to 30 June 2012. -

The Conversation Rise of Indigenous Art Speaks Volumes About Class in Australia February 24, 2014

FORT GANSEVOORT Rise of Indigenous art speaks volumes about class in Australia February 24, 2014 The children of the wealthy know that mainstream culture belongs to them. urbanartcore.eu The Conversation is running a series, Class in Australia, to identify, illuminate and debate its many manifestations. Here, Joanna Mendelssohn examines the links between Indigenous art and class. The great story of recent Australian art has been the resurgence of Indigenous culture and its recognition as a major art form. But in a country increasingly divided by class and wealth, the rise of Indigenous art has had consequences undreamed of by those who first projected it onto the international exhibiting stage. 5 NINTH AVENUE, NEW YORK, 10014 | [email protected] | (917) 639-3113 FORT GANSEVOORT The 1970s export exhibitions of Arnhem Land bark paintings and reconceptualisations of Western Desert ceremonial paintings had their origins in different regions of the oldest culture. In the following decade, urban Indigenous artists began to make their presence felt. Trevor Nickolls, Lin Onus, Gordon Bennett, Fiona Foley, Bronwyn Bancroft, Tracey Moffatt – all used the visual tools of contemporary western art to make work that was intelligent, confronting, and exhibited around the world. The continuing success of both traditional and western influenced art forms has led to one of the great paradoxes in Australian culture. At a time when art schools have subjugated themselves to the metrics-driven culture of the modern university system, when creative courses are more and more dominated by the children of privilege, some of the most interesting students and graduates are Indigenous. -

Art and Artists in Perth 1950-2000

ART AND ARTISTS IN PERTH 1950-2000 MARIA E. BROWN, M.A. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Design Art History 2018 THESIS DECLARATION I, Maria Encarnacion Brown, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in the degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. No part of this work will, in the future, be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. The work(s) are not in any way a violation or infringement of any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. The research involving human data reported in this thesis was assessed and approved by the University of Western Australia Human Research Ethics Committee. Approval # RA/4/1/7748. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature: Date: 14 May 2018 i ABSTRACT This thesis provides an account of the development of the visual arts in Perth from 1950 to 2000 by examining in detail the state of the local art scene at five key points in time, namely 1953, 1962, 1975, 1987 and 1997. -

Atomic Testing in Australian Art Jd Mittmann

ATO MIC TEST ING IN AUST RAL IAN ART JD MIT TMA NN Around the world artists have be en conce rned wit h Within a radius of 800m the dest ruction is co mplete . and Walle r. He docume nted the Austr alian New Gui nea nuclear iss ues, from the first application of atomic bomb s Over 70,000 die instantl y. campaign and its afte rmath . at Hi roshima and Nagasaki, to at omic testing, uraniu m A person stan ds lost amongst the ruins of a house . In 1946 he was se nt to Japan whe re he witnes sed mining, nuc lear waste tra nspo rt and storage, and We don’t see the chi ld’s exp ression, but it can only be the effects of the ato mic bomb. He doc umented the va st scenarios of nuclear Armageddon. The Australian artisti c one of shock and suffering. A charred tree towers ov er dest ruction from a distant vi ewpoint, spa ring the viewe r response to Bri tish atomic te sting in the 195 0s is les s the rubble. Natu re has withe red in the on slaught of hea t the ho rri fic deta ils. His sketch Rebuilding Hiroshim a well-know n, as is the sto ry of the tests . and shock waves. Simply titled Hi roshima , Albe rt Tucker’ s shows civil ians clearing away the rubble. Li fe ha s Cloaked in se crec y, the British atomic testing progra m small wate rcolour is quiet and conte mplative. -

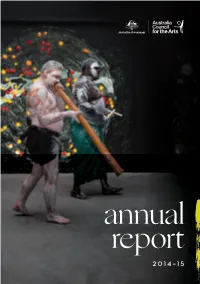

2014–15 Annual Report

annual report 2 0 1 4 – 1 5 LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Minister for the Arts Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 26 August 2015 Dear Minister, On behalf of the Board of the Australia Council, I am pleased to submit the Australia Council Annual Report for 2014–15. The Board is responsible for the preparation and content of the annual report pursuant to section 46 of the Public Governance Performance and Accountability Act 2013, the Commonwealth Authorities (Annual Reporting) Order 2011 and the Australia Council Act 2013. The following report of operations and financial statements were adopted by resolutions of the Board on the 26 August 2015. Yours faithfully, Rupert Myer AO Chair, Australia Council CONTENTS Our purpose 3 Report from the Chair 4 Report from the CEO 8 Section 1: Agency Overview 12 About the Australia Council 15 2014–15 at a glance 17 Structure of the Australia Council 18 Organisational structure 19 Funding overview 21 New grants model 28 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Arts 32 Supporting Arts Organisations 34 Major Performing Arts Companies 36 Key Organisations and Territory Orchestras 38 Achieving a culturally ambitious nation 41 Government initiatives 60 Arts Research 64 Section 2: Report on Performance Outcomes 66 Section 3: Management and Accountability 72 The Australia Council Board 74 Committees 81 Management of Human Resources 90 Ecologically sustainable development 93 Executive Team at 30 June 2015 94 Section 4: Financial Statements 96 Compliance index 148 Cover: Matthew Doyle and Djakapurra Munyarryun at the opening of the Australian Pavilion in Venice. Image credit: Angus Mordant Unicycle adagio with Kylie Raferty and April Dawson, 2014, Cirus Oz. -

Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada

Sydney College of the Arts The University of Sydney Doctor of Philosophy 2018 Thesis Towards an Indigenous History: Indigenous Art Practices from Contemporary Australia and Canada Rolande Souliere A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. Rolande Souliere i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Lynette Riley for her assistance in the final process of writing this thesis. I would also like to thank and acknowledge Professor Valerie Harwood and Dr. Tom Loveday. Photographer Peter Endersbee (1949-2016) is most appreciated for the photographic documentation over my visual arts career. Many people have supported me during the research, the writing and thesis preparation. First, I would like to thank Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney for providing me with this wonderful opportunity, and Michipicoten First Nation, Canada, especially Linda Petersen, for their support and encouragement over the years. I would like to thank my family - children Chloe, Sam and Rohan, my sister Rita, and Kristi Arnold. A special thank you to my beloved mother Carolyn Souliere (deceased) for encouraging me to enrol in a visual arts degree. I dedicate this paper to her. -

AH374 Australian Art and Architecture

AH374 Australian Art and Architecture The search for beauty, meaning and freedom in a harsh climate Boston University Sydney Centre Spring Semester 2015 Course Co-ordinator Peter Barnes [email protected] 0407 883 332 Course Description The course provides an introduction to the history of art and architectural practice in Australia. Australia is home to the world’s oldest continuing art tradition (indigenous Australian art) and one of the youngest national art traditions (encompassing Colonial art, modern art and the art of today). This rich and diverse history is full of fascinating characters and hard won aesthetic achievements. The lecture series is structured to introduce a number of key artists and their work, to place them in a historical context and to consider a range of themes (landscape, urbanism, abstraction, the noble savage, modernism, etc.) and issues (gender, power, freedom, identity, sexuality, autonomy, place etc.) prompted by the work. Course Format The course combines in-class lectures employing a variety of media with group discussions and a number of field trips. The aim is to provide students with a general understanding of a series of major achievements in Australian art and its social and geographic context. Students should also gain the skills and confidence to observe, describe and discuss works of art. Course Outline Week 1 Session 1 Introduction to Course Introduction to Topic a. Artists – The Port Jackson Painter, Joseph Lycett, Tommy McCrae, John Glover, Augustus Earle, Sydney Parkinson, Conrad Martens b. Readings – both readers are important short texts. It is compulsory to read them. They will be discussed in class and you will need to be prepared to contribute your thoughts and opinions.