Emotion Dysregulation Mediates the Relationship Between Nightmares and Psychotic Experiences: Results from a Student Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dream Poems, Experiential Narrative, and the Continuity Hypothesis

UNIVERSITY OF CANBERRA CAUGHT IN THE DANCE: DREAM POEMS, EXPERIENTIAL NARRATIVE, AND THE CONTINUITY HYPOTHESIS Niloofar Fanaiyan Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Canberra 2015 Contents Form B ............................................................................................................................. iii Abstract .............................................................................................................................. v Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... vii Part One .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................................ 2 The Dream Poem ........................................................................................................................ 5 Methodology and the Creative Product ...................................................................................... 6 A Further Prelude ....................................................................................................................... 9 Chapter One – Dreams and Dreaming ............................................................................. 13 In The Beginning ..................................................................................................................... -

Univerzita Palackého V Olomouci

UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI PEDAGOGICKÁ FAKULTA KATEDRA VÝTVARNÉ VÝCHOVY Výtvarná tvorba se zaměřením na vzdělávání VERONIKA ŠOVČÍKOVÁ KRESBA: SEN A REALITA VŠEDNÍHO DNE Bakalářská práce Vedoucí práce: Doc. Petr Jochmann Olomouc, 2014 Prohlašuji, ţe jsem diplomovou práci vypracovala samostatně a uvedla v ní předepsaným způsobem všechny pouţité prameny a literaturu. V Olomouci dne 24. dubna 2014 …………………………. Obsah ÚVOD ...........................................................................................................................................................4 1 SPÁNEK ..............................................................................................................................................5 1.1 MECHANISMUS SPÁNKU .................................................................................................................5 1.2 PŘECHOD DO NEVĚDOMÍ ................................................................................................................6 1.3 FÁZE NREM A REM SPÁNKU .........................................................................................................7 2 SEN ......................................................................................................................................................9 2.1 DEFINICE A FUNKCE SNU V ZÁVISLOSTI NA EMOCI ..........................................................................9 3 KONTRASTNÍ PŘÍSTUPY KE SNU ............................................................................................... 10 3.1 PRÁCE -

Google Deep Dream

Google Deep Dream Team Number: 12 Course: CSE352 Professor: Anita Wasilewska Presented by: Badr AlKhamissi Sameer Anand Kathryn Blecher Marolyn Liang Diego Santos Campo What Is Google Deep Dream? Deep Dream is a computer vision program created by Google. Uses a convolutional neural network to find and enhance patterns in images with powerful AI algorithms. Creating a dreamlike hallucinogenic appearance in the deliberately over-processed images. Base of Google Deep Dream Inception is fundamental base for Google Deep Dream and is introduced on ILSVRC in 2014. Deep convolutional neural network architecture that achieves the new state of the art for classification and detection. Improved utilization of the computing resources inside the network. Increased the depth and width of the network while keeping the computational budget constant of 1.5 billion multiply-adds at inference time. How Does Deep Dream Work? How Does Deep Dream Work? Deep Dream works on a Neural Network (NN) This is a type of computer system that can learn on its own. Neural networks are modeled after the functionality of the human brain, and tend to be particularly useful for pattern recognition. Biological Inspiration Biological Inspiration Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) Feed forward artificial neural network Inspired by the organization of the animal visual cortex (convolution operation) Designed to use minimal amounts of preprocessing Combine Kernel Convolution and Deep Learning Mostly used in image and video recognition, recommender systems and NLP Why Convolutional Networks? Curse of dimensionality Local connectivity Shared Weights CNN Architecture 5.1% Human Error Rate in Identifying Objects 4.94% Microsoft made it better than humans in 2014 3.46% Google inception-v3 model beat them in 2014 Digging Deeper Into The Neural Network Deep Dream’s Convolutional Neural Network must first be trained. -

Dream Poems. the Surreal Conditions of Modernism

Article Dream Poems. The Surreal Conditions of Modernism Louise Mønster Institut for Kultur og Globale Studier, Aalborg Universitet, 9220 Aalborg Ø, Denmark; [email protected] Received: 28 September 2018; Accepted: 6 November 2018; Published: 7 November 2018 Abstract: The article discusses three Swedish dream poems: Artur Lundkvist’s “Om natten älskar jag någon…” from Nattens broar (1936), Gunnar Ekelöf’s “Monolog med dess hustru” from Strountes (1955), and Tomas Tranströmer’s “Drömseminarium” from Det vilda torget (1983). These authors and their poems all relate to European Surrealism. However, they do not only support the fundamental ideas of the Surrealist movement, they also represent reservations about, and corrections to, this movement. The article illuminates different aspects of dream poems and discusses the status of this poetic genre and its relation to Surrealism throughout the twentieth century. Keywords: Nordic modernism; poetry; surrealism; dream In modernist poetry, writings are not necessarily something you write, and dreams are not necessarily something you dream. Here, the boundaries are far from fixed. Modernist works often combine different aspects, not just to break with earlier norms and categorizations, but equally to create a freer flow between forms and genres. This also applies to the relationship between poems and dreams. In the modernist tradition, many poems thematize dreams or try to adopt their form. To say about a modernist writer, that he or she writes like a dream, is not always just a normative statement. Rather, it can also be a fact. As a category, dream poems speak both of the modernist self and of the relationship of the self with the world. -

Dreamsworking at Greater Depth by Jamie Thomas

PLEASE DONATE! A message from Talk for Writing Dear Teacher/Parent/Carer, Welcome to the fifth and final batch of our English workbooks. We have now produced 40 extended English units, with audio included, all available completely free. The number of downloads of these resources has been astonishing! We’re very pleased to have been able to help schools, parents and children at what we know has been a difficult time. We also want to say a huge THANK YOU! Through your voluntary donations, we have now raised over £25,000 for Great Ormond Street Hospital and the NSPCC. For a final time, in exchange for using these booklets, we’d be grateful if you are able to make a donation to the NSPCC. We are asking for voluntary contributions of: • £5 per year group unit Schools using or sending the link to a unit to their pupils • £2 per unit Parents using a unit with their child, if they can afford to do so DONATE HERE www.justgiving.com/fundraising/tfw-nspcc The booklets are ideal for in-school bubble sessions and home learning. If they are used at home, we recommend that children should be supported by teachers through home-school links. With best wishes, Pie Corbett Talk for Writing What is Talk for Writing? Thousands of schools in the UK, and beyond, follow the Talk for Writing approach to teaching and learning. If you’re new to Talk for Writing, find more about ithere. Talk for Writing Home-school booklet DreamsWorking at greater depth by Jamie Thomas © Copyright of Jamie Thomas and Talk for Writing 2020. -

Quase Oníricas Os Sonhos E As Artes Plásticas: Uma Aproximação

1 JEANINNE SOARES SANTOS Quase Oníricas Os Sonhos e as Artes Plásticas: Uma Aproximação Brasília 2013 2 JEANINNE SOARES SANTOS Quase Oníricas Os Sonhos e as Artes Plásticas: Uma Aproximação Trabalho de conclusão de curso de Jeaninne Soares Santos, apresentado ao Departamento de Artes Visuais da Universidade de Brasília como parte dos requisitos para obter o grau de Bacharel em Artes Visuais. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Marcelo Mari. Brasília 2013 3 JEANINNE SOARES SANTOS Quase Oníricas Os Sonhos e as Artes Plásticas: Uma Aproximação Defesa realizada dia 23 de julho de 2013 junto ao Instituto de Artes da Universidade de Brasília. Monografia apresentada como um dos requisitos para obtenção do título de Bacharel submetida à aprovação da banca examinadora composta pelos seguintes membros: Prof. Me. Luiz Gallina Neto ___________________________________________________________________ Profª. Mª. Atila Ribeiro de Sousa Regiani ___________________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Marcelo Mari ___________________________________________________________________ Brasília 2013 4 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a meus pais por tudo. Agradeço em especial a bisavó Rosinha pelos anos de conselhos. Agradeço a Lincon Lacerda, por me apoiar e ajudar sempre. Agradeço meu professor orientador pelos meses de trabalho. Agradeço também a todos meus familiares, professores, amigos e inimigos que tive ao longo da vida; se não fosse por eles pode ser que eu não estivesse aqui hoje, obrigada. 5 “A Vida é Sonho” Calderón de la Barca 6 RESUMO Pelo do fascínio que meus sonhos sempre me causam quis levá-los aos olhos de outras pessoas. Anotados em cadernos e representados com papel e nanquim espero despertar nas pessoas o mesmo fascínio que tenho. Abordo neste trabalho meu universo onírico e a série de desenhos, intitulada “Quase Oníricas”. -

Charity Art Auction in Favor of the CS Hospiz Rennweg in Cooperation with the Rotary Clubs Wien-West, Vienna-International, Köln-Ville and München-Hofgarten

Rotary Club Wien-West, Vienna-International, Our Auction Charity art Köln-Ville and München-Hofgarten in cooperation with That‘s how it‘s done: Due to auction 1. Register: the current, Corona- related situation, BenefizAuktion in favor of the CS Hospiz Rennweg restrictions and changes 22. February 2021 Go to www.cs.at/ charityauction and register there; may occur at any time. please register up to 24 hours before the start of the auction. Tell us the All new Information at numbers of the works for which you want to bid. www.cs.at/kunstauktion Alternatively, send us the buying order on page 128. 2. Bidding: Bidding live by phone: We will call you shortly before your lots are called up in the auction. You can bid live and directly as if you were there. Live via WhatsApp: When registering, mark with a cross that you want to use this option and enter your mobile number. You‘re in. We‘ll get in touch with you just before the auction. Written bid: Simply enter your maximum bid in the form for the works of art that you want to increase. This means that you can already bid up to this amount, but of course you can also get the bid for a lower value. Just fill out the form. L ive stream: at www.cs.at/kunstauktion you will find the link for the auction, which will broadcast it directly to your home. 3. Payment: You were able to purchase your work of art, we congratulate you very much and wish you a lot of pleasure with it. -

2021 Iasd Annual Conference Now Virtual

FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 19 / ISSUE 2 Visit our Website IN THIS ISSUE: Contact: 2021 IASD Annual Conference NOW going VIRTUAL [email protected] All updated web pages – take a look 209.724.0889 Same 5-day program – see schedule All Keynotes remain Linda H. Mastrangelo Registration Now Open – deeply discounted Editor Call for Virtual Volunteers Joy Fatooh Call for Art – Virtual Exhibit Copy Editor Laura Atkinson IASD’s Annual Pledge Drive Meets Its Goal! Design & Layout Still Time to Enroll in the IASD Online Dream Study Richard Wilkerson Groups Program (DSGP) Office Manager IASD Online Courses Jean Campbell Executive Committee Advisor Student Research Awards – Call for Submissions Robert P. Gongloff Editorial Consultant DNJ – Call for Dream Articles and Art Delia Puiatti Dream Illustrator COVID-19 and Dreams Portal Members in the Media Hot Off the Press Dream Toon Total January New and Renewing Memberships – 47 2021 IASD ANNUAL CONFERENCE NOW VIRTUAL In order to ensure the safety of our attendees and to avoid the risk of having to cancel our conference once again due to ongoing pandemic conditions, IASD has found it necessary to hold our full 5-day conference virtually via Zoom. It will be live and interactive, with the same symposia, panels, workshops, morning dream groups, and special events offered as had been planned for the onsite program. This not only ensures the safety of participants but increases global access to the full event. Please join us, along with five world-renowned keynote speakers and more than 130 presentations from over 100 presenters around the globe. It is more than just a conference; even in its virtual format, it will be an extravaganza of fascinating presentations and special events. -

June 8, 2014 Berkeley, California, USA

I J o D R Abstracts of the 31th Annual Conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams June 4 - June 8, 2014 Berkeley, California, USA Content This supplement of the International Journal of Dream Research includes the abstracts of presenters who gave consent to the publishing. The abstracts are categorized into thematic groups and within the category sorted according to the last name of the fi rst presenter. Affi liations are included only for the fi rst author. A name register at the end is also provided. ing on their own behalf and asking for response. The Global Dream Initiative will develop a forum to see and hear the world’s dreams and to begin utilizing them to create new and more generative ways of responding to the trauma of the world, ways that are not trapped in the cultural, politi- cal, economic, and environmental approaches that now are failing us. Joining other like-minded efforts worldwide, the Contents: Global Dream Initiative is a call to action. 1. Keynotes 2. Morning Dream Groups Sleep and Dreams as Pathways to Resilience Fol- 3. Workshops lowing Trauma 4. Clinical Topics Anne Germain 5. Religion/Spiritual/Culture/Arts Pittsburgh, PA, USA 6. Education/Other Topics 7. PSI Dreaming Sleep is a fundamental brain function, and a core biological process involved in sustaining mental and physical readi- 8. Lucid Dreaming ness, especially when facing adversity. Sleep is essential for 9. Research/Theory survival and is involved in a number of biological and men- tal functions that sustain performance, including emotion 10. -

Presentation Title Listing

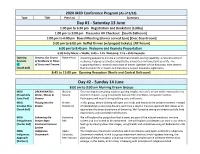

2020 IASD Conference Program (As of 3/10) Type Title Pres List Summary Day #1 - Saturday 13 June 1:00 pm to 6:30 pm Registration and Bookstore [Lobby] 1:00 pm to 5:00 pm Presenter AV Checkout [South Ballroom] 1:00 pm to 6:00 pm Board Meeting (dinner served 5pm) [Exec Boardroom] 5:00 pm to 6:00 pm Buffet Dinner (w/prepaid tickets) [NE Forum] 6:00 pm to 8:45 pm Welcome and Keynote Presentation 6:30 Entry Music – Webb; 6:45 – 7:15 Welcome; 7:15 – 8:45 Keynote Opening Dreams, Our Source Robert Hoss Dreaming appears to provide an emotional problem-solving capability, a natural source of Keynote of Resilience in Times resilience, helping us to better adapt to the adversities and uncertainties in life. The CE of Stress and Trauma supporting theory, research and a host of dream vignettes will be discussed, from dreams [South Ball] that deal with life’s impacts and transitions, to post-traumatic nightmares. 8:45 to 11:00 pm Opening Reception [North and Central Ballroom] Day #2 - Sunday 14 June 8:00 am to 9:00 am Morning Dream Groups MDG DREAM WATSU: Bhaskar This morning dream group explores gaining insights into one’s dream while immersed in the [Hospitality Water, Waves & Banerji element of water, using movements derived from the Watsu bodywork tradition. Suite Pool] Dreams Participants will need to bring bathing suits and towels. MDG Playing Into the Kirsten In this group, dream-sharing will open our minds and hearts to the present moment. Instead Creative Play Dream Backstrom of interpreting or analyzing dreams, we’ll take a playful, creative approach that allows us to [South Ball] appreciate the direct experience of dreaming. -

Dream Sharing Dream Groups

The Art of Dream Sharing and Developing Dream Groups Creative Ideas from the Dream Network Journal 1 The Art of Dreamsharing/www.Dream NetworkJournal.net ”The dream is a little hidden door in the innermost and most secret recesses of the soul, opening into the cosmic night that which was psyche long before there was any ego consciousness and which will remain psyche, no matter how far our ego- consciousness may extend. In the dream, we put on the likeness of that more universal, truer, more eternal person dwelling in the darkness of primordial night. There, the individual is still the whole and the whole is in the individual, indistinguishable from nature and bare of all egohood. It is from these all-uniting depths that the dream arises, be it ever so childish, grotesque or immoral. So flowerlike is it in its candor and veracity that it makes us blush for the Carl G. Jung deceitfulness of our lives.” 2 The Art of Dreamsharing/www.DreamNetworkJournal.net Artist Charles Catron III, Sandbox Studio, Moab, UT 3 “Doors of Perception” The Art of Dreamsharing/www.Dream NetworkJournal.net Copyright ©1993 Dream Network Journal Revised ©2002, ©2013 All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, or any portion thereof, without the written permission of the publisher. Brief quotations embodied in all articles may be reproduced giving credit to the author and the Dream Network Journal. Dream Network Journal Evolving a Dream Cherishing Culture 1025 South Kane Creek Blvd., PO Box 1026 ~ Moab, UT 84532 (435) 259-5936 http://DreamNetworkJournal.net/ [email protected] Edited and Published by H. -

Dreaiti Network Bulletin

', I I dreaiTI network bulletin volutne 8, nutnber 1 A NEWSLETTER FOR PEOPLE WHO DARE TO DREAM In thjs jssue: DREAM ART DREAM TELEPATHY LUCID & NON-LUCID DREAMS NIGHTMARES & FEAR jan/feb 1989 1 THEME FOR Auspicious Beginnings: First Lucid Dreams by Robert Wagonner 4 March/April Issue Becoming A Lucid Dreamer DREAM ANIMALS by Jill Gregory 5 & MUSICAL Not A Lucid Dreamer DREAMS by Judith Picone 6 The Banquet Artwork & Articles by Dorothy M. Rossi 8 Appreciated Let This Be A Warning To You! by Alexa Singer 10 -.,.. DREAM NETWORK BUL,ETIN DreaMagic: publishes six issues per year and has With My Brother Again an international readership. The by Dave Jenneson 11 primary focus is on dreams and Dream Trek: Dream Telepathy experiential dreamwork. Readers are invited to send in how-to tips, per by Linda Magallon 12 sonal experiences, researCh reports, Wizardreams: Fearful Dreams & Fearful Lives art work and poetry related to by Bob Trowbridge 13 dreams, and notices of existing and desired dream groups and upcoming Hellbent For Heaven: Life Becomes the Dream dream related events. We welcome by Anthony Dubetz 15 sharing and communication regarding Dream Drama all aspects of dreamwork. by Harold R. Ellis 16 10 Dream Principles DNB reserves the right to edit all material submitted for publication. by Randy A. Wasserstrom 18 Typewritten double spaced manu Features scripts or Macintosh compatible disks are preferred. Reproducible black Letters 3 and white original art work is Poetry requested. Photocopies are accept Norma Churchill 9 able. Please include a stamped, self Kyle Houbolt 15 addressed envelope with submission.