Some Chemical Composition of Walnut (Juglans Regia L.) Selections from Eastern Turkey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nutrient Comparison Chart

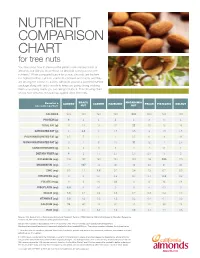

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Chart for Tree Nuts

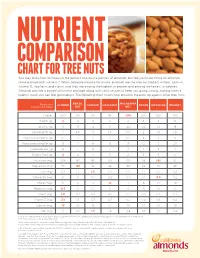

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART FOR TREE NUTS You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the highest in protein and among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a healthy snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT Calories 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 Protein (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 Total Fat (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 18 Saturated Fat (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 Polyunsaturated Fat (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 Monounsaturated Fat (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 Carbohydrates (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 Dietary Fiber (g) 4 2 1 3 2 3 3 2 Potassium (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 Magnesium (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 Zinc (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 Vitamin B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 Folate (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 Riboflavin (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 Niacin (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 Vitamin E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.2 Calcium (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 Iron (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Almond Cashew Barfi Recipe

150 Jackson St, Petone T: 568 4149 E: [email protected] ALMOND CASHEW BARFI RECIPE Almond Walnut Cashew Barfi is a healthy, quality substitute for candy that your entire family will enjoy Ingredients Makes 24 pcs 1/2 c almonds 1/2 c water 1/2 c walnuts 1/2 tsp cardamom powder 1/2 c cashew nuts 1 Tbsp sliced almonds to garnish 1 1/4 c sugar Method 1. Dry grind the walnuts, cashews and almonds in a food processor. 2. Dry roast the grounded nuts in a frying pan on low medium heat. 3. Roast them just enough so that the nuts start to give off an aroma. It will take about 4 to 5 minutes. Remove from heat and set aside. 4. Put the sugar and water together in a saucepan on medium heat. Bring to a boil to make the 1 thread syrup or on the candy thermometer it should reach 230 degrees F. 5. Turn off the heat and stir in the cardamom powder. 6. Add the nuts to the syrup and mix, and then spread over a greased 8-inch plate. Note: don’t let the syrup cool off. It must be spread while still hot. 7. Wait a few minutes until barfi is set but still soft. 8. Then cut the barfi into any shape you like (such as square, diamond, triangle). 9. Garnish each piece of barfi with sliced almonds while the barfi is still soft. 10. Allow the barfi to cool for about an hour to dry and hold its shape. -

BAY AREA MENU Seasonal Items in Green Contains Gluten Vegan

BAY AREA MENU seasonal items in green contains gluten vegan Before placing your order, please inform your server if a person in your party has a food allergy. SEASONALS FALAFEL + FETA SPRING CHICKEN UMAMI GRAIN BOWL broccoli leaf, chopped organic mesclun, shredded organic quinoa + farro, romaine, roasted beets, kale, roasted zucchini + swiss chard, pea shoots, spicy broccoli, parsley, yellow squash + asparagus, red onion, spicy sunflower mint, local feta, baked basil, shredded carrots, seeds, roasted sesame falafel, lemon garlic chili parmesan crisps, roasted tofu, roasted portobello vinaigrette chicken, pesto vinaigrette mushrooms, miso ginger 460 cal $9 sesame dressing 480 cal $11.25 615 cal $10.25 GREENS SOUPS KALE CAESAR OMG OMEGA GUACAMOLE GREENS ORGANIC LENTIL CHICKPEA shredded kale, chopped organic arugula, organic organic mesclun, tomatoes, small 160 cal $3.50 romaine, tomatoes, shaved baby spinach, cucumbers, red onion, tortilla chips, large 240 cal $5.50 parmesan, parmesan crisps, tomatoes, basil, avocado, avocado, roasted chicken, roasted chicken, fresh lime nori furikake, roasted fresh lime squeeze, lime squeeze, caesar dressing steelhead, miso sesame cilantro jalapeño vinaigrette ginger dressing 430 cal $9.75 540 cal $10.75 550 cal $13.25 HUMMUS TAHINA RAD THAI SPICY SABZI BEVERAGES shredded kale, chopped organic arugula, organic organic baby spinach, $2.50 romaine, tomatoes, mesclun, bean sprouts, shredded kale, spicy red onion, cucumbers, carrots, shredded cabbage, quinoa, spicy broccoli, HIBISCUS LIME FRESCA pita chips, -

Wholesome and Organic

1 3231 Camino de los Coches #107 Carlsbad, CA. 92009 Tel: 760-230-9282 Instagram/FB: @bigfootnaturalcafe Organic – Vegan – Wholesome – GF Available Wholesome and Organic Pasta and Rice: Mac N’ Cheez (GF) $13.75 (GF macaroni, cauliflower, broccoli, carrots cooked with house broth and house made cashew cheez sauce) Cajun Dirty Mac (GF by request) $13.75 (GF mac with roasted veggies, mushrooms, black beans and tempeh bits, in a house made creamy Creole sauce packed with leafy greens) Woodland Rice Bowl (GF) $15.25 (Sprouted brown rice, grilled portabella mushrooms, black beans, roasted sweet potatoes, grilled zucchini and avocado, drizzled with house cheez sauce and mole sauce (chocolate free).) Upgrades: Add Avocado $2.50 or house made super GF bread $2.50 Hand Crafted Tacos and Burritos: Chili Guava infused Jackfruit Tacos (GF) $13.75 (2 tacos with chili-guava infused jackfruit, slaw, maple toasted coconut chips, avocado and cashew sauce. Served with a small side of sweet potato and black bean salad) Kung Pao Chickpea Tacos (GF) $13.75 (2 tacos with roasted kung pao chickpeas, cashews and shaved brussel sprouts , red slaw, maple toasted coconut chips, avocado and kung pao sauce. Served with a small side of sweet potato and black bean salad) Tiger Stripe Burrito $14.25 (GF Option Available) (Blackened tempeh, sprouted brown rice, sweet potatoes, black beans wrapped in a warm whole wheat tortilla and smothered in our house cheez and mole sauce. Served with a side salad.) Jaka Asada Burrito $15.25 (Rosemary potatoes, chili-guava infused jackfruit (Jaka), portabella mushrooms, soaked chickpeas, hemp hearts all tossed in our Mole made with Modern Times Blackhouse Coffee Stout, wrapped in a warm whole wheat tortilla and smothered in our house cheez sauce. -

Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Walnut (Juglans Regia L.) Pellicle Tissues Reveals the Regulation of Nut Quality Attributes

life Article Comparative Proteomic Analysis of Walnut (Juglans regia L.) Pellicle Tissues Reveals the Regulation of Nut Quality Attributes Paulo A. Zaini 1, Noah G. Feinberg 1, Filipa S. Grilo 2 , Houston J. Saxe 1 , Michelle R. Salemi 3, Brett S. Phinney 3 , Carlos H. Crisosto 1 and Abhaya M. Dandekar 1,* 1 Department of Plant Sciences, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] (P.A.Z.); [email protected] (N.G.F.); [email protected] (H.J.S.); [email protected] (C.H.C.) 2 Department of Food Sciences and Technology, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] 3 Proteomics Core Facility, University of California, Davis, CA 95616, USA; [email protected] (M.R.S.); [email protected] (B.S.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 2 November 2020; Accepted: 25 November 2020; Published: 27 November 2020 Abstract: Walnuts (Juglans regia L.) are a valuable dietary source of polyphenols and lipids, with increasing worldwide consumption. California is a major producer, with ‘Chandler’ and ‘Tulare’ among the cultivars more widely grown. ‘Chandler’ produces kernels with extra light color at a higher frequency than other cultivars, gaining preference by growers and consumers. Here we performed a deep comparative proteome analysis of kernel pellicle tissue from these two valued genotypes at three harvest maturities, detecting a total of 4937 J. regia proteins. Late and early maturity stages were compared for each cultivar, revealing many developmental responses common or specific for each cultivar. Top protein biomarkers for each developmental stage were also selected based on larger fold-change differences and lower variance among replicates, including proteins for biosynthesis of lipids and phenols, defense-related proteins and desiccation stress-related proteins. -

Food Oral Immunotherapy for Severe Food Allergies

FOOD ORAL IMMUNOTHERAPY FOR SEVERE FOOD ALLERGIES ALLISON FREEMAN MD Clinical Assistant Professor, University at Buffalo Division of Allergy/Immunology & Rheumatology GOALS • REVIEW UP TO DATE GUIDANCE ON THE DEVELOPMENT AND COSTS OF FOOD ALLERGY • KNOW HOW AND WHEN TO TEST FOR FOOD ALLERGY • DISCUSS FORMS OF THERAPY THAT ARE OR SOON WILL BE MARKETED • DISCUSS FORMS OF THERAPY THAT ARE NOW AVAILABLE AT UBMD PEDIATRIC ALLERGY & IMMUNOLOGY 1. SEVERE FOOD ALLERGY MAY BE PREVENTABLE • LEARNING EARLY ABOUT PEANUT ( DUTOIT ET AL , NEJM 2015) TAUGHT US THAT OUR 20 YEAR OLD STRATEGY OF DELAYING ALLERGENIC FOOD INTRODUCTION TO INFANTS WAS WRONG • THEY SHOWED IN A LARGE RANDOMIZED TRIAL THAT; • INFANTS OFTEN HAVE POSITIVE SKIN TESTING FOR ALLERGENIC FOODS BEFORE ORAL EXPOSURE, ESPECIALLY IF THEY HAVE SIGNIFICANT ECZEMA OR ONE CLINICAL FOOD ALLERGY ALREADY- THIS IS TERMED SENSITIZATION AND MAY BE A STAGE OF THE ALLERGIC MARCH WE CAN TURN AROUND • EARLY INTRODUCTION OF EGG, MILK AND POSSIBLY CASHEW ARE SHOWN TO LESSEN LATER ALLERGY • INFANTS WITH POSITIVE SKIN TESTS TO PEANUT ARE NOT ALL DANGEROUSLY ALLERGIC • INFANTS WITH PEANUT WHEAL < 8MM OFTEN TOLERATE CHALLENGE AND IF THEY CONTINUE TO EAT IT ROUTINELY THEY HAVE >85% RISK REDUCTION FOR PEANUT ALLERGY AT SCHOOL AGE 2. FOOD ALLERGY ONCE CONFIRMED CAN BE LIFE CHANGING • ALL CHILDREN DIAGNOSED BY CLINICAL REACTION WITH CONFIRMATORY TESTING, OR BY ORAL FOOD CHALLENGE NEED TO BE TAUGHT; • HOW TO READ A FOOD LABEL AND THAT FOODS ‘PROCESSED IN A FACTORY THAT ALSO PROCESSES ‘THEIR ALLERGEN IS A SERIOUS WARNING THAT THEY SHOULD FOLLOW • HOW TO USE THEIR EPINEPHRINE, AND WHAT CONSTITUTES ANAPHYLAXIS ( ANY MULTISYSTEM REACTION TO A KNOWN ALLERGEN FOR THAT PATIENT) • THAT EPINEPHRINE HELPS MOST WHEN DELIVERED EARLY, WHICH IS WHY THEY NEED TO CARRY IT EVERYWHERE ,KEEP IT IN DATE AND STORE IT CORRECTLY The Impact of Food Allergy Diagnoses • Risk of a severe anaphylaxis is just one of many concerns. -

Preliminary Use of Cashew Kernel Oil in Clarias Gariepinus Fingerlings Diet

Int Aquat Res (2017) 9:129–139 DOI 10.1007/s40071-017-0162-5 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Preliminary use of cashew kernel oil in Clarias gariepinus fingerlings diet: comparison with fish oil and palm oil Morgane Paul Magouana Anvo . Rokyatou Sissao . Benie´ Rose Danielle Aboua . Chantal Yvette Zoungrana-Kabore´ . Athanase Kraidy Otchoumou . Essetchi Paul Kouamelan . Aboubacar Toguye´ni Received: 23 November 2016 / Accepted: 29 March 2017 / Published online: 5 April 2017 Ó The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract The present study was performed to investigate the effect of fish oil (FO), palm oil (PO), and cashew kernel oil (CKO) as the dietary lipid sources on the growth performance, tissues fatty acids com- position and economical profitability in Clarias gariepinus fingerlings. Three isonitrogenous (49.32%), isolipidic (15.18%), and isoenergetic (21 kJ/g) diets were formulated, differed only to the added lipid source and coded accordingly as D1 (fish oil), D2 (palm oil), and D3 (cashew kernel oil). Catfish fingerlings (initial body weight = 2.43 ± 0.04 g) were stocked at 1 fish/L and fed to trial diets at 5.6%. At the end of 8 weeks, C. gariepinus fingerlings fed with D1 and D3 had significantly identical growth and feed utilization efficiency. Those fed with D2 exhibited significantly and numerically low growth performance compared, respectively, to D1 and D3. Contrary to whole-body composition of fish, the muscle lipids fatty acids composition was influenced by the fatty acids profile of the dietary lipid sources. High net profit value (NPV) of 24.59$, high investment cost analysis (ICA) of 10.14$ and low benefit: cost ratio (BCR) of 2.42 were observed in fish fed with D1 while those fed with D3 allowed to have high NPV (23.15$), low ICA (7.86$) and high BCR (2.95). -

Effects of Partial Replacement of Soybean Meal with Cashew Nut Meal on Haematological Inddices and Serum Biochemical Profile of Weaned Rabbits

European Journal of Agriculture and Forestry Research Vol.9, No.2, pp. 52-58, 2021 Print ISSN: ISSN 2054-6319 (Print), Online ISSN: ISSN 2054-6327(online) EFFECTS OF PARTIAL REPLACEMENT OF SOYBEAN MEAL WITH CASHEW NUT MEAL ON HAEMATOLOGICAL INDDICES AND SERUM BIOCHEMICAL PROFILE OF WEANED RABBITS Oseni, T. A1., Amusa, H. O1., Egbinola,O. O1., Ogungbenro, S. D1., Adeoti, T. M2., Azeez, A. A2., Amoo, T.A3, and Olaoye, S. O3 1Department of Animal Health and Production Technology, Faculty of Animal and Fisheries Technology. Oyo State College of Agriculture and Technology, Igboora Oyo State, Nigeria 2Department of Animal Health and Production Technology, School of Science, Oke-Ogun Polytechnic Saki Oyo State Nigeria 3Department of Home and Rural Economics, Oyo State College of Agriculture and Technology, Igboora Oyo State, Nigeria ABSTRACT: Effects of partial replacement of soybean meal with cashew nut meal on haematological indices and serum biochemical profile of weaned rabbits were investigated using 30 weaned rabbits. The rabbits were allocated to 5 dietary treatments. Treatment was replicated thrice using two rabbits per replicate in a Completely Randomized Design (CRD). Five diet were formulated which contained 0% (control), 5, 10, 15 and 20% of cashew nut meal. The trial lasted for four (4) weeks. Results of haematological indices showed that the partial replacement of soybean meal with cashew nut meal resulted in a significant (P<0.05) difference in all the haematological indices and serum profile across the dietary treatments. Rabbits on diet 3 recorded the highest value of Packed Cell Volume while the lowest value (25.50 %) obtained for PVC was noticed in rabbits fed diet 5. -

Download Technical Dossier

Product Technical Dossier Product Black Walnut Extract CCL Product Code P02103 Specification Details Specification Identification (HPLTC) Positive Appearance Fine Powder Colour Brownish black Aroma Characteristic Flavour Characteristic Sieve Analysis % passed 100% through 80 mesh Loss on Drying Max 5% Ash Max 10% Bulk Density 40~60g/100mL Impurities/Residual Solvents Meets EP Microbiological Limits Total Viable Count Max 10,000cfu/g Yeasts & Moulds Max 1,000cfu/g E. Coli Negative/10g Salmonella Negative/25g Heavy Metal Limits Lead (Pb) Max 3ppm Cadmium (Cd) Max 1ppm Mercury (Hg) Max 0.1ppm Arsenic (As) Max 1ppm Product Code: P02103 Version: 1 Page 1 of 6 Additional Technical Information Raw Material Full Botanical / Chemical Name Juglans nigra L. Part Used Hull The material is Food Grade Yes Ratio of Material 10:1 Solvent used Water Cultivated / Wild Cultivated Harvest Method Manual Harvest Period Autumn Country of Origin China Country of Manufacture China Solubility in Alcohol Partly soluble Solubility in Water Partly soluble Shelf Life from Date of Manufacture Min 3 years Suitable for Vegetarians? Yes Suitable for Vegans? Yes This material is to be stored in a tightly sealed Storage Conditions bag/container and to be kept in a cool place away from moisture and direct sunlight. Composition Origin, Function and Percentages Ingredients Function % composition Source Black Walnut Extract Dietary Supplement 90-99% Juglans nigra L. Maltodextrin Carrier 1-10% Zea mays L Please note that surveillance testing may mean that not all the parameters stated on this specification are tested for every batch. The allergen information is supplied by the manufacturer, we have not tested for each individual allergen to ensure they are not present. -

Trees That Feed in Schools Program for Haiti Similar to the One Currently Being Run in Jamaica

WHO WE ARE • TTFF was started by Mary and Mike Mclaughlin in 2009. • Our mission is planting food bearing trees to reduce hunger, create jobs and benefit the environment. • TTFF is unique in that we don’t just provide trees but we also follow through to ensure the long term success of the tree giving project by doing all of the following: • We provide a young tree • We provide training and education for tree care • We provide information and equipment through which farmers can process fruit into flour and products for sale • We provide annual follow up to ensure that the trees are doing well and are being well cared for. • • To date, TTFF has distributed over 132,000 trees, 25 kits of processing equipment and 13,000 pounds of breadfruit flour across 10 countries. • The majority of trees are breadfruit, but distributions also commonly include other food-bearing trees, such as cashew, mango, pomegranate, avocado and others. WHY BREADFRUIT? One breadfruit tree can feed a family for a lifetime. One breadfruit weighing 3 to 5 pounds can satisfy the daily carbohydrate nutritional requirements for a family of four. The fruit is also rich in vitamins and minerals and protein. • We currently have nurseries in Jamaica and Haiti that have a capacity of 5,000 seedlings per month • We hold a large education seminar annually, with smaller training sessions throughout the year. Staffed by local experts, the seminars teach tree propagation, planting, pruning, reaping, processing, entrepreneurship and marketing and sales. • Coloring book: The TTFF is committed to environmental education. We have produced a coloring book in Kreyol, French, English and Spanish that is designed to teach children the value of planting trees and caring for the environment. -

African Cashew Nut Producers Rally Together Import System ■ in Europe, the Generalised Abidjan, Côte D’Ivoire

In brief • An overhaul for the EU African cashew nut producers rally together import system ■ In Europe, the Generalised Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire. It was System of Preferences (GSP) organised by PROMEXA (Côte is designed to allow countries of the South to export their d’Ivoire’s non-traditional agricul- products to the EU with lower tural export promotion associa- customs tariffs than those tion), ARECA (the regulatory usually applied. The total benefit authority of Côte d’Ivoire for should, in theory, be in the region of €80 billion. cotton and cashew nuts) and However, in practice, only APCAM (Mali’s permanent half the products exported assembly of chambers of agricul- actually benefit from this ture), with the financial support system. A revision of the rules was clearly needed, of PROINVEST, the EU-ACP so at the end of 2004, the partnership programme. European Commission proposed Major results of the seminar simplifying the system by keeping included the adoption of an the "Everything But Arms" scheme for products exported by industrial processing develop- least-developed countries, Photo: © Syfia international ment plan for cashew nuts in extending the GSP to include Africa and the creation of an around 300 supplementary ■ association that brings together products, introducing more African cashew nut producers before reselling them, shelled and flexible rules of origin, are worried about the new phy- processed, to Europe — has the major players in the African a clearer, fairer and more tosanitary standards for food announced that it no longer sector. Still in its preparatory simple graduation process products imported into the EU wants to buy from the African stage, this grouping will develop and, finally, establishing a the sector under the name of mechanism to encourage that came into force in January market.