Expert Report of James G. Gimpel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Newly Elected Representatives in the 114Th Congress

Newly Elected Representatives in the 114th Congress Contents Representative Gary Palmer (Alabama-6) ....................................................................................................... 3 Representative Ruben Gallego (Arizona-7) ...................................................................................................... 4 Representative J. French Hill (Arkansas-2) ...................................................................................................... 5 Representative Bruce Westerman (Arkansas-4) .............................................................................................. 6 Representative Mark DeSaulnier (California-11) ............................................................................................. 7 Representative Steve Knight (California-25) .................................................................................................... 8 Representative Peter Aguilar (California-31) ................................................................................................... 9 Representative Ted Lieu (California-33) ........................................................................................................ 10 Representative Norma Torres (California-35) ................................................................................................ 11 Representative Mimi Walters (California-45) ................................................................................................ 12 Representative Ken Buck (Colorado-4) ......................................................................................................... -

115Th Congress Roster.Xlsx

State-District 114th Congress 115th Congress 114th Congress Alabama R D AL-01 Bradley Byrne (R) Bradley Byrne (R) 248 187 AL-02 Martha Roby (R) Martha Roby (R) AL-03 Mike Rogers (R) Mike Rogers (R) 115th Congress AL-04 Robert Aderholt (R) Robert Aderholt (R) R D AL-05 Mo Brooks (R) Mo Brooks (R) 239 192 AL-06 Gary Palmer (R) Gary Palmer (R) AL-07 Terri Sewell (D) Terri Sewell (D) Alaska At-Large Don Young (R) Don Young (R) Arizona AZ-01 Ann Kirkpatrick (D) Tom O'Halleran (D) AZ-02 Martha McSally (R) Martha McSally (R) AZ-03 Raúl Grijalva (D) Raúl Grijalva (D) AZ-04 Paul Gosar (R) Paul Gosar (R) AZ-05 Matt Salmon (R) Matt Salmon (R) AZ-06 David Schweikert (R) David Schweikert (R) AZ-07 Ruben Gallego (D) Ruben Gallego (D) AZ-08 Trent Franks (R) Trent Franks (R) AZ-09 Kyrsten Sinema (D) Kyrsten Sinema (D) Arkansas AR-01 Rick Crawford (R) Rick Crawford (R) AR-02 French Hill (R) French Hill (R) AR-03 Steve Womack (R) Steve Womack (R) AR-04 Bruce Westerman (R) Bruce Westerman (R) California CA-01 Doug LaMalfa (R) Doug LaMalfa (R) CA-02 Jared Huffman (D) Jared Huffman (D) CA-03 John Garamendi (D) John Garamendi (D) CA-04 Tom McClintock (R) Tom McClintock (R) CA-05 Mike Thompson (D) Mike Thompson (D) CA-06 Doris Matsui (D) Doris Matsui (D) CA-07 Ami Bera (D) Ami Bera (D) (undecided) CA-08 Paul Cook (R) Paul Cook (R) CA-09 Jerry McNerney (D) Jerry McNerney (D) CA-10 Jeff Denham (R) Jeff Denham (R) CA-11 Mark DeSaulnier (D) Mark DeSaulnier (D) CA-12 Nancy Pelosi (D) Nancy Pelosi (D) CA-13 Barbara Lee (D) Barbara Lee (D) CA-14 Jackie Speier (D) Jackie -

AHA Colloquium

Cover.indd 1 13/10/20 12:51 AM Thank you to our generous sponsors: Platinum Gold Bronze Cover2.indd 1 19/10/20 9:42 PM 2021 Annual Meeting Program Program Editorial Staff Debbie Ann Doyle, Editor and Meetings Manager With assistance from Victor Medina Del Toro, Liz Townsend, and Laura Ansley Program Book 2021_FM.indd 1 26/10/20 8:59 PM 400 A Street SE Washington, DC 20003-3889 202-544-2422 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.historians.org Perspectives: historians.org/perspectives Facebook: facebook.com/AHAhistorians Twitter: @AHAHistorians 2020 Elected Officers President: Mary Lindemann, University of Miami Past President: John R. McNeill, Georgetown University President-elect: Jacqueline Jones, University of Texas at Austin Vice President, Professional Division: Rita Chin, University of Michigan (2023) Vice President, Research Division: Sophia Rosenfeld, University of Pennsylvania (2021) Vice President, Teaching Division: Laura McEnaney, Whittier College (2022) 2020 Elected Councilors Research Division: Melissa Bokovoy, University of New Mexico (2021) Christopher R. Boyer, Northern Arizona University (2022) Sara Georgini, Massachusetts Historical Society (2023) Teaching Division: Craig Perrier, Fairfax County Public Schools Mary Lindemann (2021) Professor of History Alexandra Hui, Mississippi State University (2022) University of Miami Shannon Bontrager, Georgia Highlands College (2023) President of the American Historical Association Professional Division: Mary Elliott, Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture (2021) Nerina Rustomji, St. John’s University (2022) Reginald K. Ellis, Florida A&M University (2023) At Large: Sarah Mellors, Missouri State University (2021) 2020 Appointed Officers Executive Director: James Grossman AHR Editor: Alex Lichtenstein, Indiana University, Bloomington Treasurer: William F. -

NMHC PAC Board Report January 2018

NMHC PAC Board Report January 2018 NMHC’s political action committee, NMHC PAC, supports the apartment industry’s legislative goals, educates Congress about multifamily housing issues and encourages participation in the political process. • 2017 NMHC PAC Receipts and Disbursements (Staff: Lisa Costello and Hailey Ray) In 2017, NMHC PAC raised $1,495,917 from 1,304 individuals from 160 NMHC member companies. The $1.25 million fundraising goal was surpassed in November. Employees of the following firms contributed $10,000 or more in 2017: Alliance Residential Company; Allied Orion Group; The Altman Companies; American Campus Communities; AMLI Residential; ARA; AvalonBay Communities; The Bozzuto Group; Bridge Investment Group; Camden Property Trust; CBRE; Continental Properties Company; Cortland Partners; Cushman & Wakefield; Equity Residential; FPA Multifamily; Gables Residential; GID; Hanover Company; Heritage Title Company of Austin; HFF; Holland Partner Group; Hunt Mortgage Group; JLL; Legacy Partners Residential; Lincoln Property Company; Madera Residential; Marcus & Millichap(IPA); Moran & Company; National Multifamily Housing Council; Pinnacle; The Preiss Company; Providence Management Company; RealPage; SARES*REGIS Group; Trammell Crow Residential; UDR; Waterton; Westdale Asset Management; Wood Partners; and ZOM Living. The top five firms for employee contributions to NMHC PAC in 2017 were Marcus & Millichap (IPA) ($165,064), JLL ($65,851) ARA ($62,850), CBRE ($55,600) and Alliance Residential Company ($52,955.) In 2017, NMHC PAC contributed $1,427,000 to over 250 congressional campaigns, leadership PACs and party committees. • NMHC PAC Co-Hosted Events A significant amount of NMHC PAC funds are used co-hosting real estate specific events allowing NMHC’s Government Affairs team to solidify relationships with the key lawmakers receiving our PAC dollars. -

Pro-Jobs Candidates Endorsed by BIPAC Action Fund Five Additional Incumbents and One State Legislator Identified and Supported by Nation’S First Business PAC for U.S

May 24, 2016 Contact: Jason Langsner For Immediate Release [email protected] | Direct (202) 776-7468 Pro-Jobs Candidates Endorsed by BIPAC Action Fund Five Additional Incumbents and One State Legislator Identified and Supported by Nation’s First Business PAC for U.S. House Races WASHINGTON DC – Today, the Business-Industry Political Action Committee’s Action Fund has announced the endorsement of six additional U.S. House of Representatives candidates running for election in 2016. They join the five U.S. Senate candidates and eight other U.S. House candidates already endorsed by the BIPAC Action Fund in this cycle. The new U.S. House candidates receiving endorsements are: • Rod Blum (R-IA 1) • Jeff Denham (R-CA 10) • Steve Knight (R-CA 25) • Lloyd Smucker (R-PA 16) • David Valadao (R-CA 21) • David Young (R-IA 3) Each have been identified by BIPAC members, state, and local employers and business organizations as being the strongest advocates for advancing private sector job creation and increasing America’s economy based on their federal and state voting records, as-well-as their stated policy positions. “As a former Member of the U.S. Congress for twelve years and a state legislator prior to then, I recognize that these legislators demonstrate what is necessary to help job creators do what they do best – grow their businesses and provide value to their customers,” said BIPAC President and Chief Executive Officer Jim Gerlach. “The California, Iowa, Pennsylvania, and our nation’s economies will be best served by these legislators being elected into the 115th Congress” continued Gerlach. -

LEGISLATIVE ACTION ALERT Four (4) PA Republicans Voted Against the Obamacare Repeal

Vol. 1, No. 2 5 MAY 2017 Pages 1 of 1 Pennsylvania Conference of Teamsters Strength in Numbers 95,000 William Hamilton, President & Eastern PA Legislative Coordinator – Joseph Molinero, Sec. -Treasurer & Western PA Legislative Coordinator – Tim O’Neill, Consultant – Dan Grace, Trustee & Legislative Advisor – Robert Baptiste, Esq. Legal Advisor LEGISLATIVE ACTION ALERT Four (4) PA Republicans voted against the Obamacare repeal See how your PA congressmen voted The PA Conference of Teamsters would like to thank the entire Democratic PA congregation and the four Republican Congressmen-Congressman Charlie Dent, Congressman Brian Fitzpatrick, Congressman Pat Meehan and Congressman Ryan Costello for voting against repealing the Affordable Health Care Act Yea Nay • Lou Barletta, R-Hazleton • Brendan Boyle, D-Philadelphia • Mike Kelly, R-Erie • Bob Brady, D-Philadelphia • Tom Marino, R-Williamsport • Matthew Cartwright, D-Scranton • Tim Murphy, R-Upper St. Clair • Ryan Costello, R-West Chester • Scott Perry, R-York • Charlie Dent, R-Allentown • Keith Rothfus, R-Oakmont • Mike Doyle, D-Pittsburgh • Bill Shuster, R-Altoona • Dwight Evans, D-Philadelphia • Lloyd Smucker, R-West Lampeter • Brian Fitzpatrick, R-Middletown • Glenn Thompson, R-Oil City • Pat Meehan, R-Reading Think tank on GOP health bill: Coverage to plummet, cancer treatment costs to skyrocket Before the Upton amendment, the center produced data stating that even with the invisible risk pool, premium surcharges for a 40-year-old with selected health conditions would be pricey. The group has not released data on these points since the amendment was introduced earlier this week, but CAP spokesperson Devon Kearns told CNN Thursday that the amendment "does next to nothing to reduce these costs." According to the center's data, a person with metastic cancer would have a surcharge of $140,510 while a person with lung, brain or other severe cancers would have a surcharge of $71,880. -

2015 Congressional Health Staff Directory

State Member Name Staffer Name Email Job Title Alabama Bradley Byrne Lora Hobbs [email protected] Senior Legislative Assistant Alabama Gary Palmer Johnny Moyer [email protected] Legislative Assistant Alabama Jeff Sessions Mary Blanche Hankey [email protected] Legislative Counsel Alabama Martha Roby Nick Moore [email protected] Teach for America Fellow Alabama Mike Rogers Haley Wilson [email protected] Legislative Assistant Alabama MO Brooks Annalyse Keller [email protected] Legislative Assistant Alabama Richard Shelby Bill Sullivan [email protected] Legislative Director Alabama Robert Aderholt Megan Medley [email protected] Deputy Legislative Director Alabama Terri Sewell Hillary Beard [email protected] Legislative Assistant Alaska Dan Sullivan Peter Henry [email protected] Legislative Director Alaska Dan Sullivan Kate Wolgemuth [email protected] Legislative Assistant Alaska Don Young Paul Milotte [email protected] Senior Legislative Assistant Alaska Don Young Jesse Von Stein [email protected] Legislative Assistant Alaska Lisa Murkowski Garrett Boyle [email protected] Legislative Assistant Arizona Ann Kirkpatrick Molly Brown [email protected] Legislative Assistant Arizona David Schweikert Katherina Dimenstein [email protected] Senior Legislative Assistant Arizona Jeff Flake Sarah Towles [email protected] Legislative Assistant -

Opposition to National Democratic

Case 1:18-cv-00443-CCC-KAJ-JBS Document 33 Filed 02/27/18 Page 1 of 26 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA : JACOB CORMAN, in his official : capacity as Majority Leader of the : No. 18-cv-00443-CCC Pennsylvania Senate, MICHAEL : FOLMER, in his official capacity as : Judge Jordan Chairman of the Pennsylvania Senate : Chief Judge Conner State Government Committee, : Judge Simandle LOU BARLETTA, RYAN COSTELLO, : MIKE KELLY, TOM MARINO, : (filed electronically) SCOTT PERRY, KEITH ROTHFUS, : LLOYD SMUCKER, and GLENN : THOMPSON, : : Plaintiffs, : : v. : : ROBERT TORRES, in his official : capacity as Acting Secretary of the : Commonwealth, and JONATHAN M. : MARKS, in his official capacity as : Commissioner of the Bureau of : Commissions, Elections, and Legislation, : : Defendants. : : PLAINTIFFS’ BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO THE NATIONAL DEMOCRATIC REDISTRICTING COMMITTEE’S MOTION TO INTERVENE AS DEFENDANT (DOC. 12) Case 1:18-cv-00443-CCC-KAJ-JBS Document 33 Filed 02/27/18 Page 2 of 26 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. COUNTER STATEMENT OF HISTORY OF THE CASE ............................. 3 II. ARGUMENT ..................................................................................................... 4 A. The NDRC Fails To Meet The Test For Intervention As A Matter Of Right Under Rule 24(a)(2). .............................................................................................. 4 1. The NDRC Lacks A Sufficiently Protectable Legal Interest In This Litigation. .......................................................................................................... -

In the United States District Court for the Middle District of Pennsylvania

Case 1:18-cv-00443-CCC-KAJ-JBS Document 3-2 Filed 02/22/18 Page 1 of 33 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA JACOB CORMAN, in his official : capacity as Majority Leader of the : Pennsylvania Senate, MICHAEL : No. 18-cv-00443-CCC FOLMER, in his official capacity as : Chairman of the Pennsylvania Senate : (filed electronically) State Government Committee, : LOU BARLETTA, RYAN COSTELLO, : THREE JUDGE COURT MIKE KELLY, TOM MARINO, : REQUESTED PURSUANT TO SCOTT PERRY, KEITH ROTHFUS, : 28 U.S.C. § 2284(a) LLOYD SMUCKER, and GLENN : THOMPSON, : : Plaintiffs, : : v. : : ROBERT TORRES, in his official : capacity as Acting Secretary of the : Commonwealth, and JONATHAN M. : MARKS, in his official capacity as : Commissioner of the Bureau of : Commissions, Elections, and Legislation, : : Defendants. : : MEMORANDUM OF LAW IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR TEMPORARY RESTRAINING ORDER AND PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Case 1:18-cv-00443-CCC-KAJ-JBS Document 3-2 Filed 02/22/18 Page 2 of 33 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. 1 II. PROCEDURAL HISTORY ............................................................................... 2 III. STATEMENT OF FACTS ................................................................................ 2 IV. STATEMENT OF QUESTION PRESENTED ................................................. 4 V. ARGUMENT .................................................................................................... -

Tom MARINO Lou BARLETTA

ELECT Governor TOM CORBETT Governor Tom Corbett has worked with the NFIB and its legislative allies to eliminate the state Inheritance Tax for small businesses and farm families, repeal the tax on business loans, and simplify key provisions in the state tax code. Corbett resolved a $4 billion deficit in the state unemployment trust fund without new taxes on employers. He signed three new laws to reduce lawsuit abuse and he enacted reforms to help reduce state regulatory hurdles faced by small businesses. Key Congressional Races Bradford ELECT Potter Tioga Glenn “G.T.” THOMPSON PA-5 Sullivan Montour Lycoming Clinton ELECT Columbia Tom MARINO Union PA-10 Centre Snyder Northumberland ELECT Lou BARLETTA PA-11 Key Pennsylvania Legislative Races ELECT ELECT ELECT ELECT ELECT ELECT Jake Matt Jeff Fred Kurt Tina CORMAN BAKER WHEELAND KELLER MASSER PICKETT SENATE DISTRICT 34 HOUSE DISTRICT 68 HOUSE DISTRICT 83 HOUSE DISTRICT 85 HOUSE DISTRICT 107 HOUSE DISTRICT 110 For a full list of NFIB endorsed candidates, or more detailed information about specific races, please visit NFIB.com/smallbizvoter percent more than the costs to large firms. large to costs the than more percent polling hours, please contact your county elections office. elections county your contact please hours, polling Pennsylvania coal jobs. coal Pennsylvania scientific data before being enacted. being before data scientific employee to small firms is approximately 60 60 approximately is firms small to employee small businesses and jeopardize over 62,000 62,000 over jeopardize and businesses small agencies to base regulations on peer-reviewed peer-reviewed on regulations base to agencies POLLS ARE OPEN 7 A.M. -

THE-PATH-TO-40-PDF.Pdf

DCCC 2018 Cycle Overview Table of Contents 1 Fast Facts on the 2018 Midterms 3 New & Different DCCC Strategies in 2018 5 o A New Political Climate 5 . Building a New Playbook for the Era of Trump 5 . Focus Groups and Polling 5 . Lessons from the Special Elections and Off-Year Elections 5 o DCCC Building changes 6 . Digital 6 . “Expansion Pod” Regional Swat team 10 . West Pod 11 . Promoting the Candidate Dollar 12 . Changes to the Independent Expenditure 15 . Diversity 16 . Training Department 17 . Cybersecurity 18 o New Democratic Base Investment and Grassroots Engagement 21 . Timeline on the Ground 21 . March into ’18 Organizers 25 . Toolbox & Claim Your Precinct program 26 . Strategic Partnerships 27 . Year of Engagement – Historic Democratic Base Turnout Program 28 How the DCCC Excelled at Core Responsibilities 33 o High Caliber Recruitment 33 . Independent Candidates who Fit their Districts 33 . Women 34 . Veterans 35 o Democratic Primary Successes 37 . DCCC’s Historic Red to Blue Success 37 . How the West was Won 38 . Partnering with the Grassroots Army 40 o Building the Largest Battlefield in a Decade 41 . Historic Number of Open Seats and Forcing Retirements 41 . Trump and Rural Districts 43 . Suburban Districts 44 . Expanding the Map & Stretching GOP Thin 46 . Republicans in Triage Mode 49 o Fundraising 51 . Committee Fundraising 51 . Candidate Fundraising 52 o Decisive Democratic Messaging Successes 54 . Healthcare 54 1 . Taxes and Medicare + Social Security 58 . Culture of Corruption 61 2 Fast Facts on the 2018 Midterms The -

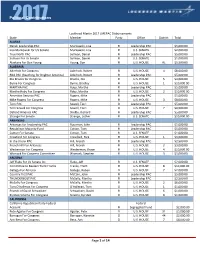

LMEPAC Disbursements – 2017

Political 2017 Contributions Lockheed Martin 2017 LMEPAC Disbursements State Member Party Office District Total ALASKA Denali Leadership PAC Murkowski, Lisa R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Lisa Murkowski for US Senate Murkowski, Lisa R U.S. SENATE $2,000.00 True North PAC Sullivan, Daniel R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Sullivan For Us Senate Sullivan, Daniel R U.S. SENATE $1,000.00 Alaskans For Don Young Young, Don R U.S. HOUSE AL $5,500.00 ALABAMA Aderholt for Congress Aderholt, Robert R U.S. HOUSE 4 $8,000.00 RBA PAC (Reaching for Brighter America) Aderholt, Robert R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Mo Brooks for Congress Brooks, Mo R U.S. HOUSE 5 $4,000.00 Byrne For Congress Byrne, Bradley R U.S. HOUSE 1 $10,000.00 MARTHA PAC Roby, Martha R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Martha Roby For Congress Roby, Martha R U.S. HOUSE 2 $10,000.00 American Security PAC Rogers, Mike R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Mike Rogers For Congress Rogers, Mike R U.S. HOUSE 3 $8,000.00 Terri PAC Sewell, Terri D Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Terri Sewell For Congress Sewell, Terri D U.S. HOUSE 7 $9,000.00 Defend America PAC Shelby, Richard R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Strange For Senate Strange, Luther R U.S. SENATE $10,000.00 ARKANSAS Arkansas for Leadership PAC Boozman, John R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Republican Majority Fund Cotton, Tom R Leadership PAC $5,000.00 Cotton For Senate Cotton, Tom R U.S.