Theatre and Magic in the Elizabethan Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

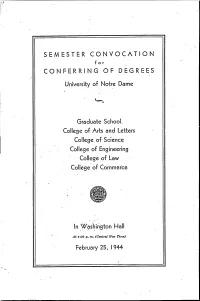

1944-02-25 University of Notre Dame Commencement Program

SEMESTER CONVOCATION for CONFERRING OF DEGREES University of Notre Dame Graduate School. College of Arts and Letters College of Science · College of Engineering College .of Law - . College of Commer·ce At 8 :OO :p. m; (Central War Time) February 25. 1944 Program I Processional March, by Orchestra The Star-Spangled Banner, by Audience Conferring of Degrees, by Riw. J. Hugh O'Donnell, c.s.c., President of the University Presentation of Commissions and Administration of Oath to the First Graduates of the Naval Officers Training Corps, by Capt. J. Richard Barry, U.S·.N., Professor of Naval Science and Tactics and Commanding Officer. Address to Graduates, by Rev. Eugene P. Burke, c.s.c., Professor of Religion Recessional March, by Orchestra Degrees Conferred At the semester convocation of February, 1944, the University of Notre Dame confers the following degrees, in course : In the Graduate School The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy on : Eugene Paul Klier,** Washington, Indiana B.S., University of Notre Dame, 1940; M.S., ibid., 1942. Major subject Metallurgy. Dissertation : The Subcrltical Decomposition of Austenite · In Chromium Steels. Brother ·Adalbert Mrowca, * of th~ Congregation of Holy Cross, NotreDame, Indiana B.S., University of Notre Dame, 1936. Major subject : Physics. Dis . sertatlon : Controlled Crystal Growth In Tantalum Ribbons. The Degree of Master of Arts on : Sister ·Ann Marie Broclonan, * of the Order of Saint Ursula, Cincinnati, Ohio A.B., Xavier University, 1929. Major subject : Latin. Dissertation : A Study of the Vocabulary In Book I of the De Virginlbus of St. Ambrose. Sister M. Roselyn Weigand, of the Order of St. -

St. John's Evangelical Church Newsletter Celebrate Freedom

St. John’s Evangelical Church 211 E. Carrol Street Kenton, Ohio 43326 (Non Profit Organization) Do Not Delay Dated Material St. John’s Evangelical Church Newsletter July 2018 211 E. Carrol Street Rev. Dr. Randall J. Forester, Senior Pastor Kenton, OH 43326 Website: www.stjohnskenton.org Church Phone: 419-673-7278 Email: [email protected] Pastor Randall cell: 724-290-3651 Church Office Hours: Monday—Friday (9 AM—1 PM) Celebrate Freedom—July 4 Hardin County Fairgrounds Celebrate Freedom will be held at the Hardin County Fairgrounds on Wednesday, July 4 from 4-10 PM. It will begin with the parade and end with fireworks at 10 PM. Events include: Grandstand concerts, kid’s zone, kids pedal pull, Evel Knievel’s motorcycle, Antique tractor display, honor- ing military and veterans, car show, and Touch-A-Truck, For more infor- mation, you can visit the website: www.celebratefreedomhardinco.com. ST. JO HN'S EVANGELICAL CHURCH 211 East Carrol Street Kenton, OH 43326 REV . DR. RANDALL J. F ORESTER , PASTOR & TEACHER Phone: 419-673-7278 (o) Phone: 724-290-3651 (c) JULY 2018 THE PASTOR’S PAGE E-mail: [email protected] With the 4th of July soon upon us, we will see Old Glory, the party line” or “vote for the lesser of two evils” in the the Stars and Stripes, proudly displayed in all sorts of man- name of compromise. Our first love is the Lord above ners. It will wave majestically throughout our land from any other. flagpoles at homes, businesses, and civic locations. It will decorate clothing, memorabilia, plates, and napkins. -

Glossary Glossary

Glossary Glossary Albedo A measure of an object’s reflectivity. A pure white reflecting surface has an albedo of 1.0 (100%). A pitch-black, nonreflecting surface has an albedo of 0.0. The Moon is a fairly dark object with a combined albedo of 0.07 (reflecting 7% of the sunlight that falls upon it). The albedo range of the lunar maria is between 0.05 and 0.08. The brighter highlands have an albedo range from 0.09 to 0.15. Anorthosite Rocks rich in the mineral feldspar, making up much of the Moon’s bright highland regions. Aperture The diameter of a telescope’s objective lens or primary mirror. Apogee The point in the Moon’s orbit where it is furthest from the Earth. At apogee, the Moon can reach a maximum distance of 406,700 km from the Earth. Apollo The manned lunar program of the United States. Between July 1969 and December 1972, six Apollo missions landed on the Moon, allowing a total of 12 astronauts to explore its surface. Asteroid A minor planet. A large solid body of rock in orbit around the Sun. Banded crater A crater that displays dusky linear tracts on its inner walls and/or floor. 250 Basalt A dark, fine-grained volcanic rock, low in silicon, with a low viscosity. Basaltic material fills many of the Moon’s major basins, especially on the near side. Glossary Basin A very large circular impact structure (usually comprising multiple concentric rings) that usually displays some degree of flooding with lava. The largest and most conspicuous lava- flooded basins on the Moon are found on the near side, and most are filled to their outer edges with mare basalts. -

Symbolic Images of the Bible Exlained in the New

SYMBOLIC IMAGES OF THE BIBLE EXLAINED IN THE NEW REVELATION THROUGH JAKOB LORBER AND GOTTFRIED MAYERHOFER (ref: www.the-new-revelation.weebly.com , www.hisnewword.org ) The facts that the known Scriptures and especially The Old Testament are spiritually encoded, that people need divine revelation to understand them, that such revelation happened when the Lord Himself explained them to His disciples and that there will come a time when He will bring His wisdom to the people in plain language are all clearly pointed in both the Old and the New Testament. We thus invite you to investigate some Bible verses pointing to the following: GOD'S MYSTERIOUS WISDOM IS TO BE REVEALED BY HIS SPIRIT. MEN KNOW NOTHING FROM THEMSELVES. THE OLD TESTAMENT IS VEILED. THE LORD OPENED IT FOR HIS DISCIPLES. PLAIN LANGUAGE PROMISED BY THE LORD IN BOTH THE OLD AND NEW TESTAMENT i (please press the roman letter at the end of the previous paragraph to see the relevant Bible verses and same to come back to the beginning/ titles list) * The previous references being noted, we will add here a collection of explanations of the spiritually encoded prophetic language of the Bible as they can be found in the New Revelation. However, please consider that this is far from being exhaustive and also that the meanings of God’s eternal and infinite words are not to be seen as restricted to just these short explanations that are given as basic instruction for Lord’s people. It is definitely, of great importance to study the Scripture in the light of these disclosures and observe how much, as a result of that, the understanding of the messages of the old prophets and Revelation increases as also the consistency between them and the teachings of Jesus; this is indeed a most compelling demonstration that God (and the God of the entire Bible) is the same yesterday, today and forever (Heb 13:8) and that the spirit of prophecy is nothing else but a testimony of the Jesus (Rev 19:10). -

The Complete Enochian Dictionary

BOOK NOTICES 523 of childrenwith languageproblems could be in- Adgt upaah zong om faaip said 'Can the wings terpretedas casting doubt on it. of the windsunderstand your voices of wonder'). An interestingand unusualfeature of B's ap- In his 49-page introduction,L traces the his- proach is her emphasis on the importanceof tory of Dee's linguistic corpus, obtained by prosodic abilities. She offers arguments,which means of his 'skryer' or medium, EdwardKel- all special language teachers should consider, ley. He also describes the writingsystem, illus- that attentionshould be focused on the melody tratedwith facsimiles from manuscripts, and the and rhythmof speech from the very beginning. ways in which Enochian resembles (or differs Over-all,this is a fine book, superiorto most from) languagesrelevant to Dee's experience: of its competitors. [DALE E. ELLIOTT,Califor- 'The21 lettersof Enochianare ... almostexactly nia State University, Dominguez Hills.] the minimumrequired to write Englishwithout any ambiguity'(47), and in both its phonology and grammarEnochian is 'thoroughlyEnglish' (41). There is a minimumof critical in the The Enochian A analysis complete dictionary: book, apparentlybecause it is not aimed at a dictionary of the Angelic language scholarly market [althoughL is an Australian as revealed to Dr. John Dee and linguist,specializing in languagesof PapuaNew Edward Kelley. By DONALD C. Guinea-Ed.] L's chapter, in fact, is entitled LAYCOCK.London: Askin, 1978. 'Enochian: Angelic language or mortal folly?' His conclusion is that 'we still do not know 272. Pp. whether it is a naturallanguage or an invented Dee (1527-1608) was 'mathematicianand language'(19), and that no one can be dogmatic AstrologerRoyal to Queen Elizabeth I, author about the matter (63). -

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES to MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to the College of Arts and Sciences Of

MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Dissertation Submitted to The College of Arts and Sciences of the UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology By Matthew Glen Minix UNIVERSITY OF DAYTON Dayton, Ohio December 2016 MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew G. APPROVED BY: _____________________________________ Sandra A. Yocum, Ph.D. Dissertation Director _____________________________________ William L. Portier, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader. _____________________________________ Anthony Burke Smith, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ John A. Inglis, Ph.D. Dissertation Reader _____________________________________ Jack J. Bauer, Ph.D. _____________________________________ Daniel Speed Thompson, Ph.D. Chair, Department of Religious Studies ii © Copyright by Matthew Glen Minix All rights reserved 2016 iii ABSTRACT MID-TWENTIETH CENTURY NEO-THOMIST APPROACHES TO MODERN PSYCHOLOGY Name: Minix, Matthew Glen University of Dayton Advisor: Dr. Sandra A. Yocum This dissertation considers a spectrum of five distinct approaches that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomist Catholic thinkers utilized when engaging with the tradition of modern scientific psychology: a critical approach, a reformulation approach, a synthetic approach, a particular [Jungian] approach, and a personalist approach. This work argues that mid-twentieth century neo-Thomists were essentially united in their concerns about the metaphysical principles of many modern psychologists as well as in their worries that these same modern psychologists had a tendency to overlook the transcendent dimension of human existence. This work shows that the first four neo-Thomist thinkers failed to bring the traditions of neo-Thomism and modern psychology together to the extent that they suggested purely theoretical ways of reconciling them. -

Facts & Features Lunar Surface Elevations Six Apollo Lunar

Greek Mythology Quadrants Maria & Related Features Lunar Surface Elevations Facts & Features Selene is the Moon and 12 234 the goddess of the Moon, 32 Diameter: 2,160 miles which is 27.3% of Earth’s equatorial diameter of 7,926 miles 260 Lacus daughter of the titans 71 13 113 Mare Frigoris Mare Humboldtianum Volume: 2.03% of Earth’s volume; 49 Moons would fit inside Earth 51 103 Mortis Hyperion and Theia. Her 282 44 II I Sinus Iridum 167 125 321 Lacus Somniorum Near Side Mass: 1.62 x 1023 pounds; 1.23% of Earth’s mass sister Eos is the goddess 329 18 299 Sinus Roris Surface Area: 7.4% of Earth’s surface area of dawn and her brother 173 Mare Imbrium Mare Serenitatis 85 279 133 3 3 3 Helios is the Sun. Selene 291 Palus Mare Crisium Average Density: 3.34 gm/cm (water is 1.00 gm/cm ). Earth’s density is 5.52 gm/cm 55 270 112 is often pictured with a 156 Putredinis Color-coded elevation maps Gravity: 0.165 times the gravity of Earth 224 22 237 III IV cresent Moon on her head. 126 Mare Marginis of the Moon. The difference in 41 Mare Undarum Escape Velocity: 1.5 miles/sec; 5,369 miles/hour Selenology, the modern-day 229 Oceanus elevation from the lowest to 62 162 25 Procellarum Mare Smythii Distances from Earth (measured from the centers of both bodies): Average: 238,856 term used for the study 310 116 223 the highest point is 11 miles. -

Nancy Huston in Self-Translation an Aesthetics of Redoublement

Corso di Dottorato in Studi Umanistici Curriculum: Studi Linguistici e Letterari XXIX ciclo Nancy Huston in Self-translation An Aesthetics of Redoublement Relatore Dottoranda Prof. Andrea Binelli Dott.ssa Giorgia Falceri A.A. 2015-2016 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I ............................................................................................... 7 I. AN INTRODUCTION TO LITERARY SELF-TRANSLATION .............. 7 1.1 FRAMING SELF-TRANSLATION STUDIES ................................................... 7 1.2 SELF-TRANSLATION IN THEORY ............................................................. 15 1.2.1 AUTHOR, TRANSLATOR AND TEXT .....................................................................18 1.2.2 RECONSIDERING TRADITIONAL CATEGORIES AND BINARY OPPOSITIONS .......... 23 1.3 SELF-TRANSLATION IN PRACTICE ........................................................... 26 1.3.1 SELF-TRANSLATORS, THESE STRANGERS. .......................................................... 26 1.3.2 TYPOLOGIES OF SELF-TRANSLATED TEXTS ........................................................ 31 1.3.3 TOWARDS A HISTORY OF SELF-TRANSLATION? ................................................. 35 1.3.4 SELF-TRANSLATION IN A SOCIOLINGUISTIC PERSPECTIVE ................................. 40 1.4 AGAINST SELF-TRANSLATION ................................................................ 46 1.5 INNOVATIVE THEORETICAL MODELS TO APPROACH THE SELF-TRANSLATED TEXT ............................................................................................................ -

Grounding the Angels

––––––––––––––––––––––– Grounding the Angels: An attempt to harmonise science and spiritism in the celestial conferences of John Dee ––––––––––––––––––––––– A thesis submitted by Annabel Carr to the Department of Studies in Religion in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Honours) University of Sydney ––––––––––––– Supervised by Dr Carole Cusack June, 2006 Acknowledgements Thank you to my darling friends, sister and cousin for their treasurable support. Thank you to my mother for her literary finesse, my father for his technological and artistic ingenuity, and my parents jointly for remaining my most ardent and loving advocates. Thank you to Dominique Wilson for illuminating the world of online journals and for her other kind assistance; to Robert Haddad of the Sydney University Catholic Chaplaincy Office for his valuable advice on matters ecclesiastical; to Sydney University Inter-Library Loans for sourcing rare and rarefied material; and to the curators of Early English Books Online and the Rare Books Library of Sydney University for maintaining such precious collections. Thank you to Professor Garry Trompf for an intriguing Honours year, and to each member of the Department of Studies in Religion who has enriched my life with edification and encouragement. And thank you most profoundly to Dr Carole Cusack, my thesis supervisor and academic mentor, for six years of selfless guidance, unflagging inspiration, and sagacious instruction. I remain forever indebted. List of Illustrations Figure 1. John Dee’s Sigillum Dei Ameth, recreated per Sloane MS. 3188, British Museum Figure 2. Edward Kelley, Ebenezer Sibly, engraving, 1791 Figure 3. The Archangel Leaving the Family of Tobias, Rembrandt, oil on canvas, 1637 Figure 4. -

Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs Vol.4: S - Z

Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs vol.4: S - Z © Neuss / Germany: Bruno Buike 2017 Buike Music and Science [email protected] BBWV E30 Bruno Antonio Buike, editor / undercover-collective „Paul Smith“, alias University of Melbourne, Australia Bibliography of Occult and Fantastic Beliefs - vol.4: S - Z Neuss: Bruno Buike 2017 CONTENT Vol. 1 A-D 273 p. Vol. 2 E-K 271 p. Vol. 3 L-R 263 p. Vol. 4 S-Z 239 p. Appr. 21.000 title entries - total 1046 p. ---xxx--- 1. Dies ist ein wissenschaftliches Projekt ohne kommerzielle Interessen. 2. Wer finanzielle Forderungen gegen dieses Projekt erhebt, dessen Beitrag und Name werden in der nächsten Auflage gelöscht. 3. Das Projekt wurde gefördert von der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Sozialamt Neuss. 4. Rechtschreibfehler zu unterlassen, konnte ich meinem Computer trotz jahrelanger Versuche nicht beibringen. Im Gegenteil: Das Biest fügt immer wieder neue Fehler ein, wo vorher keine waren! 1. This is a scientific project without commercial interests, that is not in bookstores, but free in Internet. 2. Financial and legal claims against this project, will result in the contribution and the name of contributor in the next edition canceled. 3. This project has been sponsored by the Federal Republic of Germany, Department for Social Benefits, city of Neuss. 4. Correct spelling and orthography is subject of a constant fight between me and my computer – AND THE SOFTWARE in use – and normally the other side is the winning party! Editor`s note – Vorwort des Herausgebers preface 1 ENGLISH SHORT PREFACE „Paul Smith“ is a FAKE-IDENTY behind which very probably is a COLLCETIVE of writers and researchers, using a more RATIONAL and SOBER approach towards the complex of Rennes-le-Chateau and to related complex of „Priory of Sion“ (Prieure de Sion of Pierre Plantard, Geradrd de Sede, Phlippe de Cherisey, Jean-Luc Chaumeil and others). -

Forbidden History of Europe Page Stamp 1105.Qxd

The Forbidden History of Europe - The Chronicles and Testament of the Aryan 1001 Adolf Hitler originals (as found on www.fpp.co.uk). Judging by the masterful quality of his work Adolf, the artistic genius would have made a fine career artist had others given him the chance, in a variety of media. Destiny took him along a very different pathway. Nowadays verifiable Hitler originals sell for a pathetically low $20,000. I believe they should be valued at nothing less than $US 1,000,000 each. The times are such that existence. His excellent and even acclaimed paintings failed to sell, so he went into politics. Some felt he had a gift for bidders and art reaching out to his fellow countrymen. They weren’t far wrong. connoisseurs are too afraid to put up their The Fuehrer had a lot of backing from interested parties at home and abroad. Much of it was mustered via the hand, for fear of Thule Order by Professor Karl Haushofer (Hitler’s personal vizier) if you are to believe modern historians. This being branded a particular gentleman, versed in five languages and described as “shady”, served his nation as a general in the Great Nazi. The persecution and demonisation War. Later he became German attache in Tokyo. After the 1914-1918 war he taught geo-politics at Munich extends even to his University, and became a life member of the “Luminous Lodge” and the “Thule Society”, both of which were artwork. considered irregular Masonic orders by western standards. To a degree what they say is true. -

Praxis Makes Perfect

Praxis Makes Perfect NATIONaL tHEATRE WaLES & NeON NeON NationaL Theatre WaLes & Neon Neon Praxis Makes Perfect Conceived aNd PerfOrMed by Gruff Rhys aNd Boom biP LooseLy based on tHe book seNiOr service by carlo feLtriNelli B #Ntwneonneon Neon Neon bryaN Hollon ‘Boom biP’ Gruff Rhys In 2007, Gruff Rhys and Boom Bip launched Bryan is originally from Cincinnati, Ohio Gruff Rhys is a Welsh musician, performing Cerddor Cymreig yw Gruff Rhys, sy’n perfformio the electro-pop collaboration Neon Neon. and is currently based in Los Angeles. After solo and with several bands. He was born ar ei ben ei hun a gyda sawl band. Cafodd Their first album, Stainless Style, was released starting his career as a DJ – presenting on in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire and grew ei eni yn Hwlffordd, Sir Benfro ac fe’i magwyd in 2008 and is a concept album based on the the radio and hosting club nights – he met up in Bethesda, Gwynedd in north Wales. Gruff ym Methesda, Gwynedd yng ngogledd Cymru. life of John DeLorean, founder of the DeLorean and collaborated with other producers and first found his voice as the front man of the Daeth Gruff i’r amlwg fel prif ganwr Ffa Coffi Motor Company. The album included high-profile artists including rapper Doseone. Boom Bip band Ffa Coffi Pawb (Everyone’s Coffee Beans), Pawb (Everyone’s Coffee Beans), oedd wedi’u guest appearances from the likes of The Strokes’ and Doseone’s collaborative album Circle who were signed to Ankst and became one cofrestru ag Ankstmusik a ddaethant yn un Fab Moretti, Har Mar Superstar, Cate Le Bon was noted by John Peel in the UK, and the of the leading bands on the Welsh language o brif fandiau’r byd cerddoriaeth yng Nghymru.