Historic District Design Guidelines (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“A People Who Have Not the Pride to Record Their History Will Not Long

STATE HISTORIC PRESERVATION OFFICE i “A people who have not the pride to record their History will not long have virtues to make History worth recording; and Introduction no people who At the rear of Old Main at Bethany College, the sun shines through are indifferent an arcade. This passageway is filled with students today, just as it was more than a hundred years ago, as shown in a c.1885 photograph. to their past During my several visits to this college, I have lingered here enjoying the light and the student activity. It reminds me that we are part of the past need hope to as well as today. People can connect to historic resources through their make their character and setting as well as the stories they tell and the memories they make. future great.” The National Register of Historic Places recognizes historic re- sources such as Old Main. In 2000, the State Historic Preservation Office Virgil A. Lewis, first published Historic West Virginia which provided brief descriptions noted historian of our state’s National Register listings. This second edition adds approx- Mason County, imately 265 new listings, including the Huntington home of Civil Rights West Virginia activist Memphis Tennessee Garrison, the New River Gorge Bridge, Camp Caesar in Webster County, Fort Mill Ridge in Hampshire County, the Ananias Pitsenbarger Farm in Pendleton County and the Nuttallburg Coal Mining Complex in Fayette County. Each reveals the richness of our past and celebrates the stories and accomplishments of our citizens. I hope you enjoy and learn from Historic West Virginia. -

Hclassification

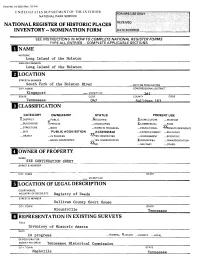

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STAThSDhPARTMHNT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME HISTORIC Long Island of the Holston AND/OR COMMON Long Island of the Holston LOCATION STREET& NUMBER South Fork of the Holston Elver _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Kingsport __. VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Tennessee 047 Sullivan 16^ HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT —PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED X.AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _ WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ^r^RIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS •^TYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED X-INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X?NO _ MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME SEE CONTINUATION SHEET STREETS. NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE __ VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Registry of Deeds STREET& NUMBER Sullivan County Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Blountville Tennessee I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Inventory of Historic Assets DATE in progress — FEDERAL ?_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Tennessee Historical Commission CITY, TOWN STATE Nashville Tennessee DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE -EXCELLENT X&ETERIORATED east _UNALTERED X.QRIGINALSITE west -RUINS XALTERED _MOVED DATE. _FA)R _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Long Island of the Holston is located along the South Fork of the Holston River just east of the junction of the North and South Forks and immediately south of the city of Kingsport, Tennessee. -

Emory and Henry College 01/30/1989

VLR Listed: 1/18/1983 NPS Form 10-900 NRHP Listed: 1/30/1989 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Eip. 10-31-84 United States Department of the interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Piaces received OCT 1 ( I935 Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic Emory and Henry College (VHLD File No. 95-98) and or common Same 2. Location street & number VA State Route 609 n/a not for publication Emory city, town X vicinity of 51 state Virginia ^^^^ Washington code county 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use X district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment -X religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation n/a no military other: 4. Owner of Property name The Holston Conference Colleges Board of Trustees, c/o Dr. Heisse Johnson street & number P.O. Box 1176 city,town Johnson City n/-a vicinity of state Tennessee 37601 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Washington County Courthouse street&number Main Street city.town Abingdon state Virginia 24210 6. Representation in Existing Surveys titieyirginia Historic Landmarks has this property been determined eligible? yes X no Division Survey File No. 95-98 date 1982 federal X_ state county local depository tor survey records Virginia Historic Landmarks divi sion - 221 Governor Street cuv.town Richmond state Virginia 23219 7. -

Fragile Fifteen

Knox Heritage Summer 2007 Quarterly ADVOCATING FOR THE PRESERVATION OF PLACES AND STRUCTURES WITH HISTORIC OR CULTURAL SIGNIFICANCE. Every year in May, National Preservation Month, 12 months. Preservation strategies are developed Knox Heritage announces The Fragile Fifteen, its for each site on the list and can include working KNOXVILLE’S list of the most endangered historic buildings and with current property owners, government offi cials, places, in order to educate the public and local citizens and/or potential new owners to preserve leaders about the plight of signifi cant historic these important parts of Knox Countyʼs heritage. resources. Knox Heritage is committed to acting as an advocate FRAGILE The historic places included on the list are selected for the endangered properties we identify each year. by the Knox Heritage Board of Directors from We invite the community to join us in our efforts to nominations received from members of Knox save our endangered heritage through advocacy and Heritage and the general public. The list provides a action. More information about this yearʼs Fragile FIFTEEN work plan for the organization for the next Fifteen can be found at www.knoxheritage.org. 1. The McClung Warehouses the buildings into loft and retail on both sides of the river, linked by interchange with I-40, combined 501–525 W. Jackson Avenue space, thus improving the tax base ferry crossings. Francis Alexander with increasing development for all Knox County residents. Ramsey settled in this corridor and pressure from Sevier County, Only three buildings remain from A structural analysis of the the 1797 Ramsey House still stands threaten the survival of one of the Feb. -

The Future of Knoxville's Past

Th e Future of Knoxville’s Past Historic and Architectural Resources in Knoxville, Tennessee Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission October 2006 Adopted by the Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission on October 19, 2006 and by the Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission on November 9, 2006 Prepared by the Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission Knoxville Historic Zoning Commissioners J. Nicholas Arning, Chairman Scott Busby Herbert Donaldson L. Duane Grieve, FAIA William Hoehl J. Finbarr Saunders, Jr. Melynda Moore Whetsel Lila Wilson MPC staff involved in the preparation of this report included: Mark Donaldson, Executive Director Buz Johnson, Deputy Director Sarah Powell, Graphic Designer Jo Ella Washburn, Graphic Designer Charlotte West, Administrative Assistant Th e report was researched and written by Ann Bennett, Senior Planner. Historic photographs used in this document are property of the McClung Historical Collection of the Knox County Public Library System and are used by MPC with much gratitude. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . .5 History of Settlement . 5 Archtectural Form and Development . 9 Th e Properties . 15 Residential Historic Districts . .15 Individual Residences . 18 Commercial Historic Districts . .20 Individual Buildings . 21 Schools . 23 Churches . .24 Sites, Structures, and Signs . 24 Property List . 27 Recommenedations . 29 October 2006 Th e Future Of Knoxville’s Past INTRODUCTION that joined it. Development and redevelopment of riverfront In late 1982, funded in part by a grant from the Tennessee sites have erased much of this earlier development, although Historical Commission, MPC conducted a comprehensive there are identifi ed archeological deposits that lend themselves four-year survey of historic sites in Knoxville and Knox to further study located on the University of Tennessee County. -

Historic District Design Guidelines As a Resource for This Document

Historic Mossy Creek District Design Guidelines Prepared by the Historic Zoning Commission Jefferson City, Tennessee December 2014 (Appendix updated March 2015) Table of Contents Credits 1. Overview . ..........................................................................................................5 1.1 Jefferson City Historic Zoning Commission .................................................5 1.2 Process for Obtaining Certificate of Appropriateness ..................................6 1.3 How to Proceed if Certificate of Appropriateness is Denied ........................6 1.4 Secretary of the Interior’s Standards: Overview .........................................7 1.5 Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Preservation ................................7 1.6 Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation ...............................8 1.7 Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Restoration ..................................9 1.8 Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Reconstruction ...........................10 1.9 Brief History of Jefferson City ....................................................................11 2. Building Materials ..........................................................................................12 2.1 Wood .........................................................................................................12 2.2 Masonry .....................................................................................................15 2.3 Architectural Metals ...................................................................................18 -

Uu0

faeapNPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 10024- 0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service MAY 2 3 Z007I National Register of Historic Places IttGiSTtK oTHStGHlC PLAGES Registration Form IPARKSEKVE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking V in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property _________________________________________________ historic name First Methodist Church, Gatlinburg other names/site number First United Methodist Church, Gatlinburg 2. Location street & number 742 Parkway N/AQ not for publication city or town Gatlinburg N/AQ vicinity state Tennessee code TN county Sevier code 155 zip code 37738 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, (.hereby certify that this ^ nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set for in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, ttje property ^ meetsyD does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Scenic Drive Area of Sequoyah Hills Neighborhood

Designation Report and Design Guidelines Scenic Drive Area of Sequoyah Hills Neighborhood Neighborhood Conservation Overlay (NC-1) Adopted by: Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission on January 19, 2006 Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission on July 13, 2006 Knoxville City Council on September 26, 2006 Acknowledgements The Designation Report and Design guidelines for the Scenic Drive Area of Sequoyah Hills Neighborhood were prepared with a great deal of assistance and cooperation from the residents of the owners. Of special assistance in this process were Nancy Bills, Lisa Gammeltoft, Kirby Bell, Robin Porter, and Kaye Stoneking. Photography was provided by the Kingston Pike/Sequoyah Hills Neighborhood Association. MPC staff involved in the preparation of this document included: Mark Donaldson, Executive Director Buz Johnson, Deputy Director Ann Bennett, Senior Planner Tim Kuhn, GIS Administrator Sarah Powell, Graphic Designer Table of Contents District Map ..................................................................................4 Introduction .................................................................................. 5 Statement of Signifi cance ............................................................5 Architectural Descriptions .......................................................... 8 Design Guidelines ........................................................................9 Guidelines Governing New Construction ............................... 11 Guidelines Governing Demolition ............................................14 -

Gay Street Commercial Historic District

NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) 0MB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Continuation Sheet Name of Property County and State Section number ___ Page __ Name of multiple property listing (if applicable) SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRI S Reference Number: 8 6002 912 Date Listed: 11/4/1986 Property Name: Gay Street Commercial Historic District County: Knox State: TN This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding t e ational Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. 1/ ~ 2':;[, Z-0 If Date of Action fr, Amended Items in Nomination: Section 5: Resource Count Based on the additional documentation and current conditions on the ground the resource count is hereby amended to reflect a total of 28 Contributing buildings and 10 Noncontributing buildings. Demolition of a number of smaller buildings and their replacement with larger buildings accounts for the change in total resource numbers. The Tennessee State Historic Preservation Office was notified of this amendment. DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NPS Form 10-900 NPS Form 10-900 (3-82)(3-02) 0MB No . 1024-0018 OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department of the Interior National National Park Service For NPS uuuse only National Register of Historic Places received SEP 2 66 1986 Inventory-NominationInventory—Nomination Form date entered NOV ^4 |ggg1986 See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries-completeentries—complete applicable sections 1. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

FHR-8-300 (11-78) United States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete appiicable sections________________ 1. Name historic Holston National Bank and/or common Hamilton National Bank 2. Location street & number 531 South Gay Street not for publication city, town Knoxvi11e vicinity of congressional district Second state Tennessee code 047 county Knox code 093 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum y building(s) X private unoccupied X commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name United American Bank street & number United American Plaza city, town Knoxvilie vicinity of state Tennessee 37902 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Knox County Courthouse, Register of Deeds Office street & number Main Avenue city, town Knoxvilie state Tennessee 37902 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title Knoxvi lie Heritage Historic Inventory has this Property been determined elegible? X yes _ no date 1^79 __federal __state __ county _X_ local depository for survey records Knoxville Heritage, Inc. P.O. Box 1746 city, town Knoxville state Tennessee 37901 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered x original site X good ^fc_ ruins X altered moved date fair " unexposed . ..* ., Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Holston National Bank is a fourteen story office building located on a 50 by 140 foot lot on the west corner of South Gay Street and Clinch Avenue in downtown Knoxville. -

Download This

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THH INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ I NAME AND/OR COMMON Long Island of the Holston LOCATION STREET& NUMBER South Fork of the Holston Elver _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Kingsport _. VICINITY OF 1st STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Tennessee 047 Sullivan 16^ HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE fLoiSTRICT _ PUBLIC -^OCCUPIED X.AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _ BUILDING(S) ^.PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X-COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL ^r^RIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS •^TYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED _ YES: UNRESTRICTED X-INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION X?NO —MILITARY —OTHER: IOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME SEE CONTINUATION SHEET STREETS NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE __ VICINITY OF LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC. Registry of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Sullivan County Court House CITY, TOWN STATE Blountville Tennessee REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Inventory of Historic Assets DATE in progress — FEDERAL X_STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Tennessee Historical Commission CITY. TOWN STATE Nashville Tennessee DESCRIPTION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE CONDITION -EXCELLENT ^^DETERIORATED east _UNALTERED X OR|GINALSITE XGOOD west -RUINS XALTERED _MOVED DATE————— _FA!R _UNEXPOSED ————————————DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Long Island of the Holston is located along the South Fork of the Holston River just east of the junction of the North and South Forks and immediately south of the city of Kingsport, Tennessee. -

South Holston Reservoir

Document Type: EIS-Administrative Record Index Field: Final Environmental Document Project Name: Northeastern Tributary Reservoirs Land Plan Project Number: 2008-32 NORTHEASTERN TRIBUTARY RESERVOIRS LAND MANAGEMENT PLAN AND ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT VOLUME V South Holston Reservoir PREPARED BY: TENNESSEE VALLEY AUTHORITY MARCH 2010 For information, contact: Tennessee Valley Authority Holston-Cherokee-Douglas Land Planning Team 106 Tri-Cities Business Park Drive Gray, Tennessee 37615 Phone: (423) 467-3801 Fax: (423) 467-3815 Page intentionally blank Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. V-1 1.1. Background .......................................................................................................................... V-1 1.2. Purpose ................................................................................................................................ V-2 2.0 PLANNING PROCESS ........................................................................................................ V-5 2.1. Planning Goals ................................................................................................................... V-10 2.2. Allocation Process .............................................................................................................. V-11 2.3. Committed Land ................................................................................................................. V-11