The Modern Vernacular of Hindustan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

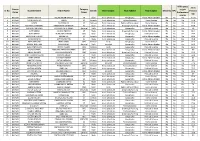

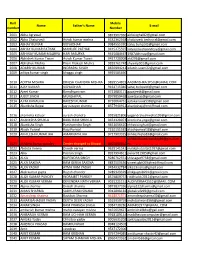

Sr.No. Course Name Student Name Father Name Category Name

Willingness XII th Course Category to join Sr.No. Student Name Father Name Gender Final Subject Final Subject Final Subject Minority BPL Percent Name Name Professional age course 1 BA Part I AAKASH MEENA GULAB SINGH MEENA ST Male Hindi Literature Geography Public Administration No No No 71.14 2 BA Part I AARTI MEROTHA TEJPAL SC Female Hindi Literature Political Science Home Science No Yes No 65.8 3 BA Part I AASHA BAJRANGLAL SC Female Hindi Literature Public Administration Home Science No No No 61.8 4 BA Part I ABHISHEK MEGHWAL RAM KARAN MEGHWAL SC Male Hindi Literature Drawing & Painting Public Administration No No Yes 69.6 5 BA Part I ABHISHEK SHARMA BANVARI LAL SHARMA General Male Hindi Literature Geography Political Science No No Yes 59 6 BA Part I AJAY MEENA JAGDISH MEENA ST Male Hindi Literature Drawing & Painting Public Administration No No No 66.4 7 BA Part I AJAY NAGAR SURAJ MAL NAGAR OBC Male Hindi Literature Geography Political Science No No Yes 74.4 8 BA Part I AKANKSHA KUMARI PANNA LAL ST Female Hindi Literature Geography Public Administration No No No 83.4 9 BA Part I AKASH KUMAR SATYANARAYAN SC Male Hindi Literature Geography Political Science No No Yes 76.8 10 BA Part I AKSA KHANAM IRSAD KHAN OBC Female Urdu Geography Home Science Yes Yes Yes 72.2 11 BA Part I AKSHAT GOUTAM RAMAVATAR General Male Sanskrit Geography Public Administration No No Yes 60.2 12 BA Part I ALISHA MANSURI ZAHID HUSAIN OBC Female Urdu Geography Political Science Yes Yes No 82.6 13 BA Part I ANJALI MEHTA CHANDRA PRAKASH MEHTA OBC Female Hindi Literature -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Minor Research Project

U.G.C. Sponsored MINOR RESEARCH PROJECT (Duration: March, 2013 – 2015) On A Study of three noteworthy dramatists in contemporary Gujarati literature (Selected plays) Presented by: DR. VARSHA L. PRAJAPATI Assistant Professor, Department of Gujarati S.L.U. Arts and H. & P. Thakore Commerce College for Women, Ellis bridge, Ahmedabad, Gujarat. Website: slucollege.org 1 Annexure - VII UNIVERSITY GRANTS COMMISSION BAHADUR SHAH ZAFAR MARG NEW DELHI – 110002 PROFORMA FOR SUBMISSION OF INFORMATION AT THE TIME OF SENDING THE FINAL REPORT OF THE WORK DONE ON THE RESEARCH PROJECT 1. Title of the Project: A study of three Noteworthy Dramatists in Contemporary Gujarati Literature (Selected Plays) 2. Name and address of the Principal Investigator: Dr. Varsha L. Prajapati, Gujarati. 3. Name and address of the Institute: S.L.U.Arts and Com. for women, Ahmedabad. 4. UGC Approval Letter No. and Date: 23-612/13(WRO) 5. Date of Implementation: 29/03/13 6. Tenure of the Project: 2 Years 7. Total Grant Allocated: Rs.1,00,000 (One Lac. Only) 8. Total Grant received: Rs.80,000(Eighty thousand only) 9. Final Expenditure: Rs.1,00,000(One lac only) 10. Title of the Project: A study of three Noteworthy Dramatists in Contemporary Gujarati Literature (Selected Plays) 2 11. Objectives of the Project : Attached sheet – page no. 1 12. Whether objectives were achieved: Attached sheet. – pageno. 1 to 8 13. Achievements from the Project: Attached sheet.- Page no. 9 14. Summary of the findings: Attached sheet.- page no. 10 to 25 15. Contribution to the society: Attached sheet.- page no. -

One and Three Bhairavas: the Hypocrisy of Iconographic Mediation Gregory Price Grieve

Revista de Estudos da Religião Nº 4 / 2005 / pp. 63-79 ISSN 1677-1222 One and Three Bhairavas: The Hypocrisy of Iconographic Mediation Gregory Price Grieve The artist-as-anthropologist, as a student of culture, has as his job to articulate a model of art, the purpose of which is to understand culture by making its implicit nature explicit. [T]his is not simply circular because the agents are continually interacting and socio-historically located. It is a non-static, in-the-world model. Joseph Kosuth1, “The Artist as Anthropologist” (1991[1975]) Iconography is a hypocritical term. On the face of it, “iconography” simply denotes the critical study of images (Panofsky 1939; 1955). Yet, one must readily admit that iconography stems from the fear of images (Mitchell 1987). In fact, iconography can be defined as a strategy for writing over images. But why fear images? Iconography’s zealotry—from idols made in the likeness of God to fetishes made in the image of capital—stems from the terror of the material. Accordingly, to proceed in an analysis of iconography, one must make explicit what most religious discursive systems must by necessity leave implict religion is never just “spirit.” Whether iconophobia or iconophilia, whether iconoclastic or idolatry, what all religions have in common is that they rely on matter for their dissemination. Even speech, the most reified communication, relies on air and the physicality of the human body. Accordingly, to write about, rather than write over, religious images, we need to return to the material. Stop and take a look at the god-image of Bhairava, a fierce form of Shiva from the Nepalese city of Bhaktapur2. -

Collected Research Papers in Prakrit & Jainlogy

Collected Research Papers in Prakrit & Jainlogy (Volume II) Edited by NALINI JOSHI (With Preface) Seth H.N.Jain Chair Firodia Publications University of Pune March 2013 NALINI JOSHI 1 Collected Research Papers in Prakrit & Jainlogy (Volume II) Edited by Dr. Nalini Joshi (With Preface) Assisted by Dr. Kaumudi Baldota Dr. Anita Bothra Publisher : Seth H.N.Jain Chair Firodia Publications (University of Pune) All Rights Reserved First Edition : March 2013 For Private Circulation Only Price : Rs. 300/- D.T.P. Work : Ajay Joshi 2 Preface with Self-assessment Impartial self-assessment is one of the salient features in post-modernism. An attempt has been made in this direction in the present preface cum editor's note cum publisher's note. All the research-papers collected in this book are the outcome of the research done jointly with the help of the assistance given by Dr. Anita Bothara and Dr. Kaumudi Baldota, under the auspices of Seth H.N.Jaina Chair which is attached to the Dept. of philosophy, University of Pune. All the three roles viz. author, editor and publisher are played by Dr. Nalini Joshi, Hon. Professor, Jaina Chair. While looking back to my academic endeavor of twenty-five years, up till now, a fact comes up glaringly the whole span of my life is continuous chain of rare opportunities in the field of Jaina Studies. In the two initial decades while working in the "Comprehensive and Critical Dictionary of Prakrits', under the able editorship of Late Dr.A.M.Ghatage, I got acquaintance, with almost five hundred original Prakrit texts. -

Story of King Vikramadhithya Contents

Story of king Vikramadhithya There are two versions to this great story. The north Indian version was called “Simhasan Bhatheesi(throne with 32 steps) and the south Indian version was called “Periya ezhuthu Vikramadhithan kadhai(The story of Vikramadhithya in big letters).I have followed the south Indian version, I have summarized the stories in to a very short form as the original stories are very lengthy , with very many descriptions. This is possibly the greatest gift to the Indian lads and lasses that I can give Contents Story of king Vikramadhithya ................................................................... 1 1. Bhoja Raja gets Vikramadithya’s throne .................................. 3 2. Who was Vikramadithya? ........................................................ 5 3. Vikramadhithya and Vetala –I ................................................ 12 4. Vikramadhithya and Vetala –IRetold by ................................ 14 5. Vikramadhithya and Vetala Stories 2-6 ................................. 17 6. Vikramadhithya and Vetala Stories 7-10 ............................... 24 7. Vikramadhithya and Vetala Stories 11-16 ............................. 33 8. Vikramadhithya and Vetala stories 17-24 and story of Vetala ............................................................................................... 42 9. The story of Elalaramba told by the third doll -Komalavalli .. 56 10. The story of Chamapakavalli as told by fourth doll Mangala Kalyana Valli. ......................................................................... -

Journalists Report 20Dec19 Final R1

A STUDY ON THE KILLINGS OF AND ATTACKS ON JOURNALISTS IN INDIA, 2014–2019, AND JUSTICE DELIVERY IN THESE CASES. Published in December 2019 Geeta Seshu Urvashi Sarkar Photo credit: http://www.catchnews.com/india-news/mining-money-and-mafia-why-journalist-sandeep-kothari- had-to-die-1434961701.html Research funded by Thakur Family Foundation, Inc Highlights • There were 40 killings of journalists between 2014-19. Of these, 21 have been confirmed as being related to their journalism. • Of the over 30 killing of journalists since 2010, there were only three convictions. The cases were J Dey, killed in 2011; Rajesh Mishra, killed in 2012 and Tarun Acharya, killed in 2014. • In a fourth case of journalist Ram Chandra Chhattrapati, killed in 2002, it took 17 years for justice to be delivered in the life imprisonment order for Dera Sacha Sauda chief Gurmeet Ram Rahim • The study documented 198 serious attacks on journalists in the period between 2014-19, including 36 in 2019 alone. • Journalists have been fired upon, blinded by pellet guns, forced to drink liquor laced with urine or urinated upon, kicked, beaten and chased. They have had petrol bombs thrown at their homes and the fuel pipes of their bikes cut. • Journalists covering conflict or news events were specifically targeted by irate mobs, supporters of religious sects, political parties, student groups, lawyers, police and security forces. • Attacks on women journalists in the field were found to have increased. The targeted attacks on women journalists covering the Sabarimala temple entry were sustained and vicious. A total of 19 individual attacks of women journalists are listed in this report. -

Date : 24/10/2018

RESULT Date Of Birth Cate Home SN Application ID Applicant Name Father's/ Husband's Name Gender PH ENGLISH HINDI (dd-mm-yyyy) gory District (WPM) (WPM) DATE : 24/10/2018 SAMASTI 1 EXA/234000001 KAILASH SHARMA NARAYAN SHARMA 1989-07-03 Male EBC No Absent Absent PUR 2 EXA/234000002 MUNNA KUMAR PRADEEP PRASAD GOND 20-02-1994 Male ST No ROHTAS Absent Absent PURBI 3 EXA/234000003 YASH RAJ SUKHAL RAM 14-08-1996 Male SC No Absent Absent CHAMPA PASHCHI 4 EXA/234000004 MD NEYAJ AHAMAD ABDULLAH MIYAN 1991-06-05 Male EBC No Absent Absent M KHAGARI 5 EXA/234000005 PINTU KUMAR JAY PRAKASH SHARMA 1996-04-02 Male EBC No Absent Absent A SAMASTI 6 EXA/234000006 GAURAV BHARADWAAJ PRASHANT KUMAR RAY 1998-10-12 Male GEN No Absent Absent PUR PASHCHI 7 EXA/234000007 IFTEKHAR AHMAD ABDULLAH MIYAN 25-06-1997 Male EBC No 8.00 11.20 M MUZAFFA 8 EXA/234000008 CHANDAN RAM NAGENDRA RAM 1992-05-01 Male SC No Absent Absent RPUR SAMASTI 9 EXA/234000009 BITTU KUMARI NARAYAN SHARMA 24-05-1994 Female EBC No Absent Absent PUR DARBHA 10 EXA/234000011 MD ABU NASAR MD AKHTAR 20-09-1982 Male EBC No Absent Absent NGA 11 EXA/234000012 OMPRAKASH KUMAR SATYANARAYAN RAM 25-03-1992 Male SC No ROHTAS 21.80 19.40 PASHCHI 12 EXA/234000013 MD RAJA ANSARI SHAKIL ANSARI 1994-04-11 Male EBC No Absent Absent M 13 EXA/234000015 MD ISHTEYAQUE MD ISRAFIL 1991-05-12 Male EBC No SHEOHAR Absent Absent PASHCHI 14 EXA/234000016 ASHFAK AHMAD ABDULLAH MIYAN 1998-02-02 Male EBC No Absent Absent M 15 EXA/234000017 POOJA KUMARI PRADEEP PRASAD GOND 1999-10-01 Female ST No ROHTAS Absent Absent 16 EXA/234000019 -

Elements of Hindu Iconography

6 » 1 m ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY. ELEMENTS OF HINDU ICONOGRAPHY BY T. A. GOPINATHA RAO. M.A., SUPERINTENDENT OF ARCHiEOLOGY, TRAVANCORE STATE. Vol. II—Part II. THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD :: :: MADRAS 1916 Ail Rights Reserved. i'. f r / rC'-Co, HiSTor ir.iL medical PRINTED AT THE LAW PRINTING HOUSE MOUNT ROAD, MADRAS. MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA Sadasivamurti and Mahasada- sivamurti, Panchabrahmas or Isanadayah, Mahesamurti, Eka- dasa Rudras, Vidyesvaras, Mur- tyashtaka and Local Legends and Images based upon Mahat- myas. : MISCELLANEOUS ASPECTS OF SIVA. (i) sadasTvamueti and mahasadasivamueti. he idea implied in the positing of the two T gods, the Sadasivamurti and the Maha- sadasivamurti contains within it the whole philo- sophy of the Suddha-Saiva school of Saivaism, with- out an adequate understanding of which it is not possible to appreciate why Sadasiva is held in the highest estimation by the Saivas. It is therefore unavoidable to give a very short summary of the philosophical aspect of these two deities as gathered from the Vatulasuddhagama. According to the Saiva-siddhantins there are three tatvas (realities) called Siva, Sadasiva and Mahesa and these are said to be respectively the nishJcald, the saJcald-nishJcald and the saJcaW^^ aspects of god the word kald is often used in philosophy to imply the idea of limbs, members or form ; we have to understand, for instance, the term nishkald to mean (1) Also iukshma, sthula-sukshma and sthula, and tatva, prabhdva and murti. 361 46 HINDU ICONOGEAPHY. has foroa that which do or Imbs ; in other words, an undifferentiated formless entity. -

Roll Number Name Father's Name Mobile Number E-Mail 2001 Abha Agrawal 9873907960 [email protected] 2002 Abha Chaturvedi

Roll Mobile Name Father's Name E-mail number Number 2001 Abha Agrawal 9873907960 [email protected] 2002 Abha Chaturvedi Ashok kumar mishra 9532362368 [email protected] 2003 ABHAY KUMAR VIDYADHAR 9984555330 [email protected] 2004 ABHAY KUMAR PATHAK MANI JEE PATHAK 9415275597 [email protected] 2005 ABHINAY KUMAR MAURYA HARI MAURYA 9415684467 [email protected] 2006 Abhishek Kumar Tiwari Ashok Kumar Tiwari 9457728009 [email protected] 2007 Abhishek Mishra Prem Prakash Mishra 9839761748 [email protected] 2008 ADARSH KUMAR INDRAPAL SINGH 8650994242 [email protected] 2009 aditya kumar singh bhaggu singh 9935585690 2010 ADITYA MISHRA DINESH CHANDRA MISHRA 9899554819 [email protected] 2011 AJAY KUMAR VIDYADHAR 9161715046 [email protected] 2012 Ajeet Kumar Ramdhyan ram 9721083171 [email protected] 2013 AJEET SINGH MUNSHI PAL 8979059468 [email protected] 2014 AJITA KANAUJIA RAKESH KUMAR 8726064761 [email protected] 2015 Akanksha Bajpai jay narayan sharma 8377940912 [email protected] 2016 akanksha katiyar suresh chandra 9935821806 [email protected] 2017 AKANKSHA SHUKLA BABU RAM SHUKLA 9454328073 [email protected] 2018 Akanksha Singh Purshpendra Singh 9651656420 [email protected] 2019 Akash Porwal Raju Porwal 7210151583 [email protected] 2020 AKHILESH KUMAR JHA AMARNATH JHA 9717903325 [email protected] [email protected] 2021 akhilesh kumar pandey Center changed to Bhopal 8602093910 m 2022 Akshita Verma Dinesh verma -

My HANUMAN CHALISA My HANUMAN CHALISA

my HANUMAN CHALISA my HANUMAN CHALISA DEVDUTT PATTANAIK Illustrations by the author Published by Rupa Publications India Pvt. Ltd 2017 7/16, Ansari Road, Daryaganj New Delhi 110002 Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Illustrations Copyright © Devdutt Pattanaik 2017 Cover illustration: Hanuman carrying the mountain bearing the Sanjivani herb while crushing the demon Kalanemi underfoot. The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verified to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in a retrieval system, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-81-291-3770-8 First impression 2017 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The moral right of the author has been asserted. This edition is for sale in the Indian Subcontinent only. Design and typeset in Garamond by Special Effects, Mumbai This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated, without the publisher’s prior consent, in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published. To the trolls, without and within Contents Why My Hanuman Chalisa? The Text The Exploration Doha 1: Establishing the Mind-Temple Doha 2: Statement of Desire Chaupai 1: Why Monkey as God Chaupai 2: Son of Wind Chaupai 3: -

A History of Hindi Literature

T HE H ER IT AGE O F IN DIA T n V . Z A R IAH he Right Revere d S A , Bishop of D or na k al . N F A A R . A . D . L IT T . Oxo n . M J . R QU H , , ( ) bli A[rea dy pu she d. a dd K . M . A . The He rt of Bu hism . J SAUNDERS , A . M A . M . D . a . R . M . EV . H sok J MACP AIL , , I d P ain in . P rinc i al P W a a . n ian t g p ERCY BRO N , C lcutt an . RI A a a . RE V . E P . CE B . K rese Liter ture , ‘ a A I H D . LIT 1 . a . The S mkhy System BERR EDALE KEIT , A M . P al a a ain . s ms of M r th a S ts NICOL MACNICOL , , D LITT In Me press. H n K N SB R and PH IL L IP . ym s of the T amil éaivite S a i nts . I G U Y S K . ar a i a a A . L H The m M m ms . BERRIEDA E KEIT , D LITT ‘ ' z S u b jects p roposed a nd volu mes u n de r prefi a m z on . S ANSK R IT AN D PA LI LITE R AT U R E . H n MA D N L L d . A . A . C O E fro d . ym s m the Ve as Prof , Oxfor A n P .