Review of Arrangements for Overseas Skills Recognition, Upgrading and Licensing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glittering Gould

RECORDS Stephen \X4dsworth Glittering Gould wenty-five years ago, CBS released odder, wearing coat, scarf, cap, and celebrates 25 years of Gould on disc Ta recording of Bach's Goldberg gloves in summer, never meeting the with four releases that travel from Variations played on the piano by press except by phone, avoiding planes Scarlatti to Scriabin to Gould himself, Glenn Gould, an eccentric young and pollution like the plague, still with the accent on Bach. Canadian. The critics said he'd made a sitting hunched on that ridiculous Pablo Casals wrote in his auto mechanical sequence expressive, ab chair, which hasn't been replaced or biography, "For the past eighty years 1 sorbing, and wholly interesting, and even altered an eighth of an inch in the have started each day in the same everyone loved it, especially a genera last 30 years. manner .... I go to the piano, and I tion of piano students whose daily Recordings were the voices of his play two preludes and fugues of Bach rigors were greatly eased by this vision silence, and they came hard and fast— It is a sort of benediction on the of a somehow passionate Bach. Yet this Byrd, Beethoven, Brahms, Bizet of all house." Gould's newest record. Bach: was certainly the cleanest, least roman people (Chopin and Liszt conspicuous Preludes, Fughettas and Fugues, is a tic Bach on records. ly absent), Schoenb'erg and Hindemith, benediction on the house. His playing Gould played against the piano in a among others, all subject to the whim, it has a sprightly exactitude just this side sense. -

Course Wise Universities List.Xlsx

HUMANITIES & PURE SCIENCE SL USA UK CANADA FRANCE ITALY GERMANY IRELAND SWEDEN SWISS AUSTRALIA NEWZELAND SINGAPORE NO London School of University of Toronto INSEAD Business University of Dublin - Stockholm School University of University of Singapore 1 Harvard University Bocconi University University of Munich University of Zurich Economics (Rothman) School Trinity College of Economics Melbourne Auckland Management School Massachusetts Institute University of British Paris School of Swiss Federal Institute National University 2 University of Oxford University of Bologna University of Mannheim University College Dublin Lund University Monash University University of Otago of Technology Columbia (Sauder) Economics of Technology Zurich of Singapore Nanyang University of Toulouse School of Stockholm University of New Victoria University 3 Princeton University University of Alberta University of Gothenburg University of Bonn Griffith College University of St Gallen Technological Cambridge Economics University South Wales of Wellington University Aukland London Business Universite Toulouse MIB Trieste School of 4 Stanford University University of Montreal University of Cologne Dublin City College Uppsala University University of Sydney University of Schoool 1 Capitole Management Technology Johann Wolfgang Goethe University of California - University College University of Aix- National University of University of 5 York University Bologna Business School University Frankfurt am Massey University Berkeley London Marseille Ireland - Galway Queensland -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION The phenomenon of bogus providers in higher education is nothing new, as the authors of this timely study demonstrate in their section on the historical overview of diploma mills and bogus accrediting bodies. But the problem actually goes far beyond the 19 th century. In the appendices to volume II of Rashdall's masterful work The Universities of Europe in the Middle Ages (Powicke and Emden, Oxford, rev. ed. 1936), there are listed some 23 establishments which various contemporary and later authorities claimed to be universities, but for which no adequate evidence existed. 1 Indeed, Pope Alexander IV issued a Bull against the chanter of the Cathedral of Reims in 1258 for falsely claiming exemption from residential requirements for attending the non-existent studium generale in that city when he was actually living in another country and claiming benefices there: The dean of the Reims cathedral chapter was forbidden to allow him to enjoy this subterfuge. And in another cited case, the Bishop of Albi excommunicated the entire town because of their false claim to have established a university - a decision which was reversed on appeal to the ecclesiastical court of the Archbishop of Bourges. 2 Thus already by the end of the 13 th Century we have evidence that false claims of university privileges were extant, and also that the competent authorities were no more consistent in their approaches to the problem in that time than are their modern counterparts. Given the sorry history of bogus providers and dubious (at best) claims on their behalf, the efforts of the late Twentieth and the Twenty-First Centuries need now to accomplish what has not succeeded for over 800 years - a concerted effort to combat fraudulent academic providers and their supporters, including the so-called quality assurance agencies that supposedly give them legitimacy. -

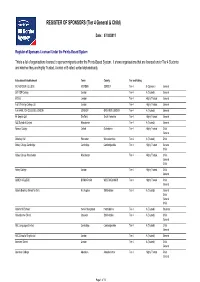

HTS WEB Report Processor V2.1

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4 General & Child) Date : 22/06/2011 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under the Points-Based System. It shows organisations that are licensed under Tier 4 Students and whether they are Highly Trusted, A-rated or B-rated, sorted alphabetically. Educational Establishment Town County Tier and Rating 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE MORDEN SURREY Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 360 GSP College London Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 4N ACADEMY LIMITED London Tier 4 B (Sponsor) General 5 E Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A & S Training College Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON LONDON GREATER LONDON Tier 4 A (Trusted) General A+ English Ltd Sheffield South Yorkshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A2Z School of English Manchester Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Abacus College Oxford Oxfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abberley Hall Worcester Worcestershire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Cambridgeshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbey College Manchester Manchester Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbey College London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child ABBEY COLLEGE BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbots Bromley School for Girls Nr. Rugeley Staffordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbot's Hill School Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Students Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Staffordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child -

Warnborough College, Dkt. No. 95-164-ST

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20202 ____________________________________ In the Matter of WARNBOROUGH COLLEGE, Respondent. Docket Nos. 95-164-ST 96- 60-SF Student Financial Assistance Termination and Fine Proceedings ____________________________________ Appearances: David B. Adler, Esq., Seattle, Washington, and John Walsh of Brannagh, Barrister, Norfolk Island, South Pacific, for Warnborough College. Paul G. Freeborne, Esq., and Russell B. Wolff, Esq., Office of the General Counsel, United States Department of Education, Washington, D.C., for Student Financial Assistance Programs. Before: Judge Ernest C. Canellos DECISION On November 2, 1995, the office of Student Financial Assistance Programs (SFAP), of the U.S. Department of Education (ED), issued a notice of its intent to terminate the eligibility of Warnborough College, Oxford, England, (College) to participate in the federal student financial assistance programs authorized under Title IV of the Higher Education Act of 1965, as amended, (Title IV), 20 U.S.C. § 1070 et seq. and 42 U.S.C. § 2751 et seq. In response to that notice, on November 9, 1995, counsel for the College requested a hearing in this matter. Subsequently, on April 24, 1996, SFAP notified the College that it was proposing to fine the College $350,000 for various alleged violations of the Title IV regulations. After the College appealed the fine action, the termination and fine procedures were joined. The parties filed briefs and made evidentiary submissions and, on July 22-23, 1996, I conducted an evidentiary hearing as to both matters. A verbatim record was made at the hearing and a copy of the transcript was provided to each side. -

The Non-Representation of the Agricultural Labourers in 18Th and 19Th Century English Paintings

The Non-Representation of the Agricultural Labourers in 18th and 19th Century English Paintings The Non-Representation of the Agricultural Labourers in 18th and 19th Century English Paintings An Exploration into the Artistic Conventions followed by the Aristocracy and Landowning Classes in Representations of the Agricultural Labourers in the 18th and the First Decades of the 19th Century in English Paintings of the Period, which Rarely Depicted the True State of Such People By Penelope McElwee The Non-Representation of the Agricultural Labourers in 18th and 19th Century English Paintings By Penelope McElwee This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Penelope McElwee All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-8705-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-8705-2 DEDICATION This book has evolved from a PhD Thesis completed in 2015 whilst studying with Warnborough College Ireland. The journey was often challenging, sometimes frustrating, but mostly a great learning curve and immensely rewarding. I hope the work will allow those interested in the Social History of Art to understand why English paintings of the eighteenth and for most of the nineteenth century, look as they do. Also, to appreciate the hard life the agricultural labourers of the period were made to endure at the hands of the wealthy minority. -

Tier 4 - Used - Period: 01/01/2012 to 31/12/2012

Tier 4 - Used - Period: 01/01/2012 to 31/12/2012 Organisation Name Total More House School Ltd 5 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE 65 360 GSP College 15 4N ACADEMY LIMITED † 5 E Ltd 10 A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON 20 A+ English Ltd 5 A2Z School of English 40 Abacus College 30 Abberley Hall † Abbey College 120 Abbey College Cambridge 140 Abbey College Manchester 55 Abbots Bromley School for Girls 15 Abbotsholme School 25 ABC School of English Ltd 5 Abercorn School 5 Aberdeen College † Aberdeen Skills & Enterprise Training 30 Aberystwyth University 520 ABI College 10 Abingdon School 20 ABT International College † Academy De London 190 Academy of Management Studies 35 ACCENT International Consortium for Academic Programs Abroad, Ltd. 45 Access College London 260 Access Skills Ltd † Access to Music 5 Ackworth School 50 ACS International Schools Limited 50 Active Learning, LONDON 5 Organisation Name Total ADAM SMITH COLLEGE 5 Adcote School Educational Trust Limited 20 Advanced Studies in England Ltd 35 AHA International 5 Albemarle Independent College 20 Albert College 10 Albion College 15 Alchemea Limited 10 Aldgate College London 35 Aldro School Educational Trust Limited 5 ALEXANDER COLLEGE 185 Alexanders International School 45 Alfred the Great College ltd 10 All Hallows Preparatory School † All Nations Christian College 10 Alleyn's School † Al-Maktoum College of Higher Education † ALPHA COLLEGE 285 Alpha Meridian College 170 Alpha Omega College 5 Alyssa School 50 American Institute for Foreign Study 100 American InterContinental University London Ltd 85 American University of the Caribbean 55 Amity University (in) London (a trading name of Global Education Ltd). -

HTS WEB Report Processor V2.1

REGISTER OF SPONSORS (Tier 4 General & Child) Date : 07/02/2011 Register of Sponsors Licensed Under the Points-Based System This is a list of organisations licensed to sponsor migrants under the Points-Based System. It shows organisations that are licensed under Tier 4 Students and whether they are Highly Trusted, A-rated or B-rated, sorted alphabetically. Educational Establishment Town County Tier and Rating 3 D MORDEN COLLEGE MORDEN SURREY Tier 4 B (Sponsor) General 360 GSP College London Tier 4 A (Trusted) General 5 E Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A & S Training College Ltd London Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A A HAMILTON COLLEGE LONDON LONDON GREATER LONDON Tier 4 A (Trusted) General A+ English Ltd Sheffield South Yorkshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General A2Z School of English Manchester Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Abacus College Oxford Oxfordshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abberley Hall Worcester Worcestershire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Child Abbey College Cambridge Cambridge Cambridgeshire Tier 4 Highly Trusted General Child Abbey College Manchester Manchester Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Child Abbey College London Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General ABBEY COLLEGE BIRMINGHAM WEST MIDLANDS Tier 4 Highly Trusted Child General Abbots Bromley School for Girls Nr. Rugeley Staffordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) General Child General Child Abbot's Hill School Hemel Hempstead Hertfordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Students Abbotsholme School Uttoxeter Staffordshire Tier 4 A (Trusted) Child General ABC Languages Limited Cambridge -

College 2019-20

2019-20 Code List of Colleges and Scholarship Programs Alabama - United States Alabama ID. School Name & Address Years Status 0086 SOUTHRN UNION ST COMM COLL OPE, 1701 LAFAYETTE PKWY, OPELIKA AL 36801 2 2 0087 BISHOP STATE CMTY COLL CARVER, 414 STANTON STREET, MOBILE AL 36617 2 2 0094 FREDD STATE TECH COLLEGE, 3401 ML KING JR BLVD, TUSCALOOSA AL 35401 2 2 0103 WALLACE CMNTY COLG SPARKS CMPS, PO BOX 580, EUFAULA AL 36072 2 2 0177 ENTERPRISE STATE CC AVIATION, 3405 S US HWY 231, OZARK AL 36360 2 2 0184 ALABAMA STHRN CMTY COLL THOMAS, PO BOX 2000, THOMASVILLE AL 36784 2 2 0187 TRENHOLM STATE CC PATTERSON, PO BOX 10048, MONTGOMERY AL 36108 2 2 0188 NORTHWST-SHOALS CMTY COLL, P O BOX 2545, MUSCLE SHLS AL 35662 2 2 0189 CENTRL ALABAMA C C CHILDSBRG, 1675 CHEROKEE RD, ALEX CITY AL 35010 2 2 0193 REID STATE TECHNICAL COLLEGE, PO BOX 588, EVERGREEN AL 36401 2 2 0207 TRENHOLM ST COMM COLL TRENHOLM, PO BOX 10048, MONTGOMERY AL 36108 2 2 0213 BEVILL STATE CMTY COLLEGE, 101 STATE ST, SUMITON AL 35148 2 2 0320 SONAT FOUNDATION SCHOLARSHIP, DARLENE O’DONNELL, PO BOX 2563, BIRMINGHAM AL 35202 0 3 0528 WALLACE STATE HANCEVILLE, PO BOX 2000, HANCEVILLE AL 35077 2 2 0548 AIR FORCE ROTC SCHOLARSHIPS, 551 E MAXWELL BLVD, MAXWELL AFB AL 36112 0 3 0706 ATHENS STATE UNIVERSITY, 300 N BEATY ST, ATHENS AL 35611 2 2 0715 CENTRAL ALABAMA CMNTY COLLEGE, 1675 CHEROKEE RD, ALEX CITY AL 35010 2 2 0720 BEVILL STATE COMMUNITY COLLEGE, 1411 INDIANA AVE, JASPER AL 35501 2 1 0723 BEVILL STATE CMTY COLL BREWER, 2631 TEMPLE AVENUE N, FAYETTE AL 35555 2 2 0805 HERITAGE CHRISTIAN -

Institution Code Institution Title a and a Co, Nepal

Institution code Institution title 49957 A and A Co, Nepal 37428 A C E R, Manchester 48313 A C Wales Athens, Greece 12126 A M R T C ‐ Vi Form, London Se5 75186 A P V Baker, Peterborough 16538 A School Without Walls, Kensington 75106 A T S Community Employment, Kent 68404 A2z Management Ltd, Salford 48524 Aalborg University 45313 Aalen University of Applied Science 48604 Aalesund College, Norway 15144 Abacus College, Oxford 16106 Abacus Tutors, Brent 89618 Abbey C B S, Eire 14099 Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar Sc 16664 Abbey College, Cambridge 11214 Abbey College, Cambridgeshire 16307 Abbey College, Manchester 11733 Abbey College, Westminster 15779 Abbey College, Worcestershire 89420 Abbey Community College, Eire 89146 Abbey Community College, Ferrybank 89213 Abbey Community College, Rep 10291 Abbey Gate College, Cheshire 13487 Abbey Grange C of E High School Hum 13324 Abbey High School, Worcestershire 16288 Abbey School, Kent 10062 Abbey School, Reading 16425 Abbey Tutorial College, Birmingham 89357 Abbey Vocational School, Eire 12017 Abbey Wood School, Greenwich 13586 Abbeydale Grange School 16540 Abbeyfield School, Chippenham 26348 Abbeylands School, Surrey 12674 Abbot Beyne School, Burton 12694 Abbots Bromley School For Girls, St 25961 Abbot's Hill School, Hertfordshire 12243 Abbotsfield & Swakeleys Sixth Form, 12280 Abbotsfield School, Uxbridge 12732 Abbotsholme School, Staffordshire 10690 Abbs Cross School, Essex 89864 Abc Tuition Centre, Eire 37183 Abercynon Community Educ Centre, Wa 11716 Aberdare Boys School, Rhondda Cynon 10756 Aberdare College of Fe, Rhondda Cyn 10757 Aberdare Girls Comp School, Rhondda 79089 Aberdare Opportunity Shop, Wales 13655 Aberdeen College, Aberdeen 13656 Aberdeen Grammar School, Aberdeen Institution code Institution title 16291 Aberdeen Technical College, Aberdee 79931 Aberdeen Training Centre, Scotland 36576 Abergavenny Careers 26444 Abersychan Comprehensive School, To 26447 Abertillery Comprehensive School, B 95244 Aberystwyth Coll of F. -

Legislative Assembly

18003 LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY Wednesday 23 September 2009 __________ The Speaker (The Hon. George Richard Torbay) took the chair at 10.00 a.m. The Speaker read the Prayer and acknowledgement of country. AUDITOR-GENERAL'S REPORT Mr Speaker tabled, pursuant to the section 38E of the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983, the Performance Audit Report of the Auditor-General entitled, "Administering Domestic Waterfront Tenancies: Land and Property Management Authority, and Marine Authority of New South Wales", dated September 2009. Ordered to be printed. NOTICES OF MOTIONS The SPEAKER: Order! A trend has developed for members to give notices of motions that are lengthy, contain argument, unbecoming expressions, and which at times are given in the spirit of mockery. I remind members that such notices are out of order. In accordance with Standing Order 137 the Clerks are able to amend such notices under my authority to ensure they conform to the standing orders. However, if members persist in giving notices that are out of order I will rule them to be out of order and not published in the Business Paper. I remind members that a notice of motion should be a self-contained proposal and be drafted in such a way that the House is able to express a decision when the motion is moved. Members should avail themselves of the advice of the Clerks if they are unsure whether a notice is in an acceptable form prior to giving it. BUSINESS OF THE HOUSE Notices of Motions General Business Notices of Motions (General Notices) given. REAL PROPERTY AMENDMENT (LAND TRANSACTIONS) BILL 2009 Agreement in Principle Debate resumed from 22 September 2009. -

Organisation Country Australian Department of Foreign

IELTS Global Recognition System Organisation Country Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Afghanistan British Embassy - Afghanistan Afghanistan Islamic Student Union of Afghanistan Afghanistan Kateb University Afghanistan Kateb University Afghanistan The American University of Afghanistan Afghanistan Agriculture University Albania Albanian British Chamber of Commerce Albania British Embassy - Albania Albania European University of Tirana Albania Politeknichian University Albania Universitty “Aleksandër Xhuvani” Albania University "Aleksandër Moisiu" Albania University “Eqrem Çabej” Albania University “Fan S. Noli” Albania University “Ismail Qemali” Albania University “Luigj Gurakuqi” Albania University of New York Tirana Albania British Embassy - Algeria Algeria Laiki Bank Algeria Ministry of Education - Algeria Algeria Ministry of Interior Affairs Algeria ODTU University Algeria The Canadian Embassy, Algeria Algeria Yapi Kredi Bank Algeria Colegio San Albano Temperley Argentina Colegio San Pedro Apostol Argentina Columbia School Argentina IAE Business School Argentina ISEN Argentina National University Mision- Argentina School of Chemistry and Natural Science Argentina St. Albans College Argentina Universidad Austral-IAE Argentina Universidad de San Andrés Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Argentina American University of Armenia Armenia Russian Armenian Slavonic State University Armenia Academia International Australia Academies Australasia Australia Academy Management Pty Ltd. Australia Academy of English Australia