The Pleasures and Uses of Televisual Historical Caricature Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scotland's 'Forgotten' Contribution to the History of the Prime-Time BBC1 Contemporary Single TV Play Slot Cook, John R

'A view from north of the border': Scotland's 'forgotten' contribution to the history of the prime-time BBC1 contemporary single TV play slot Cook, John R. Published in: Visual Culture in Britain DOI: 10.1080/14714787.2017.1396913 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Author accepted manuscript Link to publication in ResearchOnline Citation for published version (Harvard): Cook, JR 2018, ''A view from north of the border': Scotland's 'forgotten' contribution to the history of the prime- time BBC1 contemporary single TV play slot', Visual Culture in Britain, vol. 18, no. 3, pp. 325-341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14714787.2017.1396913 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please view our takedown policy at https://edshare.gcu.ac.uk/id/eprint/5179 for details of how to contact us. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 1 Cover page Prof. John R. Cook Professor of Media Department of Social Sciences, Media and Journalism Glasgow Caledonian University 70 Cowcaddens Road Glasgow Scotland, United Kingdom G4 0BA Tel.: (00 44) 141 331 3845 Email: [email protected] Biographical note John R. Cook is Professor of Media at Glasgow Caledonian University, Scotland. He has researched and published extensively in the field of British television drama with specialisms in the works of Dennis Potter, Peter Watkins, British TV science fiction and The Wednesday Play. -

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS in SCIENCE FICTION and FANTASY (A Series Edited by Donald E

Gender and the Quest in British Science Fiction Television CRITICAL EXPLORATIONS IN SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY (a series edited by Donald E. Palumbo and C.W. Sullivan III) 1 Worlds Apart? Dualism and Transgression in Contemporary Female Dystopias (Dunja M. Mohr, 2005) 2 Tolkien and Shakespeare: Essays on Shared Themes and Language (ed. Janet Brennan Croft, 2007) 3 Culture, Identities and Technology in the Star Wars Films: Essays on the Two Trilogies (ed. Carl Silvio, Tony M. Vinci, 2007) 4 The Influence of Star Trek on Television, Film and Culture (ed. Lincoln Geraghty, 2008) 5 Hugo Gernsback and the Century of Science Fiction (Gary Westfahl, 2007) 6 One Earth, One People: The Mythopoeic Fantasy Series of Ursula K. Le Guin, Lloyd Alexander, Madeleine L’Engle and Orson Scott Card (Marek Oziewicz, 2008) 7 The Evolution of Tolkien’s Mythology: A Study of the History of Middle-earth (Elizabeth A. Whittingham, 2008) 8 H. Beam Piper: A Biography (John F. Carr, 2008) 9 Dreams and Nightmares: Science and Technology in Myth and Fiction (Mordecai Roshwald, 2008) 10 Lilith in a New Light: Essays on the George MacDonald Fantasy Novel (ed. Lucas H. Harriman, 2008) 11 Feminist Narrative and the Supernatural: The Function of Fantastic Devices in Seven Recent Novels (Katherine J. Weese, 2008) 12 The Science of Fiction and the Fiction of Science: Collected Essays on SF Storytelling and the Gnostic Imagination (Frank McConnell, ed. Gary Westfahl, 2009) 13 Kim Stanley Robinson Maps the Unimaginable: Critical Essays (ed. William J. Burling, 2009) 14 The Inter-Galactic Playground: A Critical Study of Children’s and Teens’ Science Fiction (Farah Mendlesohn, 2009) 15 Science Fiction from Québec: A Postcolonial Study (Amy J. -

Festival at a Glance

FESTIVAL AT A GLANCE WEDNESDAY 22 10:00-11:00 BREAK 11:30-12:30 BREAK 14:00-15:00 BREAK 15:45-16:45 BREAK 17:45-18:30 18:30-21:00 P Masterclass: 11:00-11:30 P Meet the Controllers: 12:30-14:00 F Gamechanger: 15:00-15:45 P Edinburgh Does 16:45-17:45 L MacTaggart Lecture: Free coaches to The FH Screening: Love Island T Channel 4 Charlotte Moore, L It’s all about me... SA Music from Nancy Daniels, T How to Cash In Catchphrase with B Branded Michaela Coel Museum of Scotland Vanity Fair, ITV. S Meet the Controller: Random Acts Live Pitch BBC One on TV: Joanna Lumley Hannah Haynes, Discovery on the Streaming Roy Walker Entertainment Network depart from the EICC Exclusive Preview Damian Kavanagh, 11:00 - 12:00 F Tomorrow’s World with Clive Tulloh Harpist and Composer S Meet the Controller: Goldrush S Meet the Cocktail Reception 18:30 - 19:15 of Episode One with BBC Three SA Music from of TV 12:45 - 13:45 Zai Bennett, Sky UK 15:10 -15:40 Controllers: Richard 16:45 - 17:35 Cast & Crew Q&A 19:00 - 20:30 MK Too Posh Hannah Haynes, S The Insider’s Guide T Meet the Canadians: MK Commissioner LF Lightning Talk: Watsham, Hilary Rosen BT Pre-MacTaggart & Steve North, UKTV to Produce? Harpist and Composer to Building Your Opportunities for Interview: Luke Hyams, How to make a Lecture Drinks A+E Networks Opening UK Producers Green Production 16:45 - 17:35 P5 Speed Meetings: Audience on YouTube Head of Originals, MK Introductory Night Reception: The 12:45 - 13:30 15:10 - 15:40 10:00 - 16:00 MK Lessons from YouTube EMEA Address: SA Join us for a Museum of -

ABC2 Program Schedule

1 | P a g e ABC2 Program Guide: National: Week 19 Index Index Program Guide .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Sunday, 7 May 2017 .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Monday, 8 May 2017 ............................................................................................................................................ 8 Tuesday, 9 May 2017 .......................................................................................................................................... 13 Wednesday, 10 May 2017................................................................................................................................... 18 Thursday, 11 May 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 23 Friday, 12 May 2017 ............................................................................................................................................ 29 Saturday, 13 May 2017 ....................................................................................................................................... 35 Marketing Contacts ..................................................................................................................................................... 40 2 | P a g e ABC2 Program -

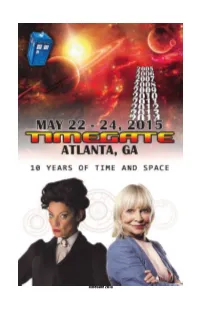

Timegate 2015

TimeGate 2015 WELCOME TO TIMEGATE 2015 We’re thrilled you’ve joined us for our 10th YEAR OF TIMEGATE in our new hotel, the Marriott Century Center!! The past decade has brought lots of exciting developments in the worlds of Doctor Who and sci-fi/fantasy in general. We’ve got lots to celebrate… not least the fact that it’s also 10 years since Who returned to TV screens in a big way and became more popular than ever! To commemorate this, we’ve put together a thrilling assortment of guests and events bridging classic and new Doctor Who… not to mention the latest in other fantastical movies, TV, com- ics, and books. We have two new stations for your assistance — Information Services and the TimeGate Store. If you are new to TimeGate, join our First-Timers panel and tour on Friday at 7:00 p.m. Buy your Charity Cabaret tickets, TimeGate shirts, and VIP guest autograph/photograph tickets at the new TimeGate store! Also, be sure to explore the wonders of our bigger dealers room! PLEASE support our Charity Cabaret on Saturday night. There is a $5.00 additional admission. It is well worth the small additional expense for the extra performances by our guests, who are doing this for the charity. 100% of the proceeds will go to support the Nepal Youth Foundation. Please buy your ticket at the TimeGate store before the event. Let us transport you into the worlds of Doctor Who (among many others), as we ’phase’ you away to a weekend of fun-filled imagination! Many thanks to our Immortals, our sponsors, the great staff of the Marriott Century Center, and to our fantastic Senior Directors, Directors and staff, who make TimeGate such a huge success! Special thanks to Robert Lloyd for creating this program book, and to Tony Cade and Challenges Games and Comics for giving us space for making badges! Alan Siler Susan Rey IN MEMORY GEORGE COCKRELL TimeGate has been going for ten years now, and George was there for nearly all of it, even though he lived in Illinois. -

The Acid House a Film by Paul Mcguigan

100% PURE UNCUT IRVINE WELSH The Acid House a film by Paul McGuigan a Zeitgeist Films release The Acid House a film by Paul McGuigan based on the short stories from “The Acid House” by Irvine Welsh Starring Ewen Bremner Kevin McKidd Maurice Roëves Martin Clunes Jemma Redgrave Introducing Stephen McCole Michelle Gomez Arlene Cockburn Gary McCormack Directed by Paul McGuigan Screenplay by Irvine Welsh Director of Photography Alasdair Walker Editor Andrew Hulme Costume Designers Pam Tait & Lynn Aitken Production Designers Richard Bridgland & Mike Gunn Associate Producer Carolynne Sinclair Kidd Produced by David Muir & Alex Usborne FilmFour presents a Picture Palace North / Umbrella Production produced in association with the Scottish Arts Council National Lottery Fund, the Glasgow Film Fund and the Yorkshire Media Production Agency UK • 1999 • 112 mins • Color • 35mm In English with English subtitles Dolby Surround Sound a Zeitgeist Films release The Acid House a film by Paul McGuigan Paul McGuigan’s THE ACID HOUSE is a surreal triptych adapted by Trainspotting author Irvine Welsh from his collection of short stories. Combining a vicious sense of humor with hard- talking drama, the film reaches into the hearts and minds of the chemical generation, casting a dark and unholy light into the hidden corners of the human psyche. Part One The Granton Star Cause The first film of the trilogy is a black comedy of revenge, soccer and religion that come together in one explosive story. Boab Coyle (STEPHEN McCOLE) thinks he has it all, a ‘tidy’ bird, a job, a cushy number living at home with his parents and a place on the kick-about soccer team the Granton Star. -

Scary Poppins Returns! Doctor Who: the Eighth Doctor, Liv and Helen Are Back on Earth, but This Time There’S No Escape…

ISSUE: 136 • JUNE 2020 WWW.BIGFINISH.COM SCARY POPPINS RETURNS! DOCTOR WHO: THE EIGHTH DOCTOR, LIV AND HELEN ARE BACK ON EARTH, BUT THIS TIME THERE’S NO ESCAPE… DOCTOR WHO ROBOTS THE KALDORAN AUTOMATONS RETURN BIG FINISH WE MAKE GREAT FULLCAST AUDIO WE LOVE STORIES! DRAMAS AND AUDIOBOOKS THAT ARE AVAILABLE TO BUY ON CD AND OR ABOUT BIG FINISH DOWNLOAD Our audio productions are based on much-loved TV series like Doctor Who, WWW.BIGFINISH.COM Torchwood, Dark Shadows, @BIGFINISH Blake’s 7, The Avengers, THEBIGFINISH The Prisoner, The Omega Factor, Terrahawks, Captain BIGFINISHPROD Scarlet and Survivors, as BIG-FINISH well as classics such as HG BIGFINISHPROD Wells, Shakespeare, Sherlock Holmes, The Phantom of the SUBSCRIPTIONS Opera and Dorian Gray. If you subscribe to our Doctor We also produce original BIG FINISH APP Who The Monthly Adventures creations such as Graceless, The majority of Big Finish range, you get free audiobooks, Charlotte Pollard and The releases can be accessed on- PDFs of scripts, extra behind- Adventures of Bernice the-go via the Big Finish App, the-scenes material, a bonus Summer eld, plus the Big available for both Apple and release, downloadable audio Finish Originals range featuring Android devices. readings of new short stories seven great new series: ATA and discounts. Girl, Cicero, Jeremiah Bourne in Time, Shilling & Sixpence Secure online ordering and Investigate, Blind Terror, details of all our products can Transference and The Human be found at: bgfn.sh/aboutBF Frontier. BIG FINISH EDITORIAL WE’RE CURRENTLY in very COMING SOON interesting times, aren’t we? The COVID-19 pandemic has changed all our lives in recent ABBY AND ZARA months, with lockdown becoming a part of our everyday routine. -

Rufus Hound and Katy Brand to Join the West End Cast Of

PRESS RELEASE: FRIDAY 14 FEBRUARY RUFUS HOUND AND KATY BRAND TO JOIN THE WEST END CAST OF Everybody’s Talking About Jamie, the award-winning fabulous and feel good musical sensation, is delighted to announce that actor, comedian and presenter Rufus Hound and actor, writer and comedian Katy Brand will be joining the cast this March to play Hugo/Loco Chanelle and Miss Hedge at the Apollo Theatre in London’s West End. Katy Brand said: Joining the cast of Everybody’s Talking About Jamie is a truly thrilling opportunity for me. If I could tell my teenage self that I would one day have the chance to perform in a huge hit show on the West End stage, that girl would pinch herself. Jamie gets to realise his dream every night, and now so do I! Rufus Hound said: I'm absolutely thrilled to be going into the cast of Everybody's Talking About Jamie - a brilliant, brave and British smash hit. I have been waxing for the last year in anticipation and am currently so tucked I may as well be a Ken doll. Bring. It. On. Nica Burns, Producer of Everybody’s Talking About Jamie said: We are delighted that Katy Brand will be joining the cast as Miss Hedge and Rufus Hound as Hugo / Loco Chanelle. They will both bring their own incredible talent to their roles and make them their own. Katy Brand will play Miss Hedge from 3 March until 20 June 2020 and Rufus Hound will play Hugo/Loco Chanelle from 16 March until 30 May 2020. -

Doctor Who and the Politics of Casting Lorna Jowett, University

Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett, University of Northampton Abstract: This article argues that while long-running science fiction series Doctor Who (1963-89; 1996; 2005-) has started to address a lack of diversity in its casting, there are still significant imbalances. Characters appearing in single episodes are more likely to be colourblind cast than recurring and major characters, particularly the title character. This is problematic for the BBC as a public service broadcaster but is also indicative of larger inequalities in the television industry. Examining various examples of actors cast in Doctor Who, including Pearl Mackie who plays companion Bill Potts, the article argues that while steady progress is being made – in the series and in the industry – colourblind casting often comes into tension with commercial interests and more risk-averse decision-making. Keywords: colourblind casting, television industry, actors, inequality, diversity, race, LGBTQ+ 1 Doctor Who and the politics of casting Lorna Jowett The Britain I come from is the most successful, diverse, multicultural country on earth. But here’s my point: you wouldn’t know it if you turned on the TV. Too many of our creative decision-makers share the same background. They decide which stories get told, and those stories decide how Britain is viewed. (Idris Elba 2016) If anyone watches Bill and she makes them feel that there is more of a place for them then that’s fantastic. I remember not seeing people that looked like me on TV when I was little. My mum would shout: ‘Pearl! Come and see. -

Topps DW Signature Series Checklist FINAL

Topps Doctor Who Signature Series - Base Cards 1 The First Doctor 34 Androgar 67 Professor Alison Docherty 2 The Second Doctor 35 Davros 68 Danny Pink 3 The Third Doctor 36 Jenny, The Doctor's Daughter 69 Alonso Frame 4 The Fourth Doctor 37 Adric 70 Missy 5 The Fifth Doctor 38 Gwen Cooper 71 Ood Sigma 6 The Sixth Doctor 39 The Master 72 Psi 7 The Seventh Doctor 40 Rosita 73 Leela 8 The Eighth Doctor 41 General Sanchez 74 Roman Groom 9 The Ninth Doctor 42 Francine Jones 75 John Benton 10 The Tenth Doctor 43 Slitheen 76 Cathica Santini Khadeni 11 The Eleventh Doctor 44 The Teller 77 Winifred Bambera 12 The Twelfth Doctor 45 Diagoras 78 Cybermen 13 Bill 46 Oliver Morgenstern 79 Craig Owens 14 Clara Oswald 47 Nyssa 80 Kate Stewart 15 Amy Pond 48 The Silent 81 The Beast from The Pit 16 Rory Williams 49 Victoria Waterfield 82 The Valeyard 17 River Song 50 Vislor Turlough 83 Gantok 18 Rose Tyler 51 Toby Zed 84 Group Captain Ian Gilmore 19 Mickey Smith 52 Ianto Jones 85 Ashildr 20 Martha Jones 53 Ms. Delphox 86 Clive Jones 21 Donna Noble 54 Weeping Angel 87 Kirsty McLaren 22 Captain Jack Harkness 55 Strax 88 Von Weich 23 Osgood 56 Jenny Flint 89 Arnold Golightly 24 Sarah Jane Smith 57 Madame Vastra 90 Cline 25 Jo Grant 58 Zygon 91 Jamie McCrimmon 26 Susan Foreman 59 Mels 92 Ace 27 Malohkeh 60 Hila Tacorien 93 Colony Sarff 28 Captain Knight 61 Romana 94 The Controller 29 Jackie Tyler 62 Lilith 95 Mel 30 Mordred 63 Kahler-Tek 96 Pete Tyler 31 The Master 64 Kahler-Jex 97 Clifford Jones 32 Dalek 65 Steven Taylor 98 Richard Nixon 33 Blon Fel-Fotch -

The Midlands Essential Entertainment Guide

Midlands Cover - Feb_Mids Cover - August 28/01/2013 18:00 Page 1 MIDLANDS WHAT’S MIDLANDS ON WHAT’S THE MIDLANDS ESSENTIAL ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE ISSUE 326 FEBRUARY 2013 www.whatsonlive.co.uk £1.80 ISSUE 326 FEBRUARY 2013 MICKY FLANA TOURS THEG REGIONAN INSIDE Harry Hill back on the circuit THE DEFINITIVE interview inside LISTINGS GUIDE Tara Fitzgerald on making her RSC debut interview inside Sheila Reid Benidorm actress leaves her scooter behind... interview inside PART OF MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON MAGAZINE GROUP PUBLICATIONS GROUP MAGAZINE ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS OF PART What’sOn MAGAZINE GROUP Hot Right Now and appearing in Brum... ISSN 1462-7035 GRAND_FP- Feb13_Layout 1 28/01/2013 14:51 Page 1 Great Theatre at the Grand! MON 4 - SAT 9 FEB TUES 12 - SAT 16 FEB SUN 17 - TUES 19 FEB ‘BRILLIANT! ITEXPLODESLIKEGLITTERINGFIREWORKS’ Russia’s acclaimed ballet company BILL KENWRIGHT BY ARRANGEMENT WITH THE REALLY USEFUL GROUP PRESENTS returns to Wolverhampton following a sensational season in 2012 The Nutcracker Coppélia Swan Lake Performed by LYRICS BY MUSIC BY TIM RICE ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER The Russian State Ballet & Orchestra of Siberia STARRING KEITH JACK WED 20 FEB FRI 22 FEB TUES 26 FEB - SAT 2 MARCH SPOT © Eric Hill / SalSPOT lTd, 2012 licEnSEd by SalSPOT lTd. funwiTHSPOT.cOm WED 6 - SAT 9 MARCH ALSO BOOKING TUES 19 - SAT 30 MARCH SAT 23 FEBRUARY THE BILLY FURY YEARS TUES 12 - SAT 16 MARCH WOLVERHAMPTON MUSICAL COMEDY COMPANY FOOTLOOSE TUESDAY 2 - WEDNESDAY 3 APRIL HORMONAL HOUSEWIVES SAT 6 APRIL JIM DAVIDSON SUNDAY 7 APRIL THE SOLID SILVER 60s SHOW -

2016 Topps Doctor Who Extraterrestrial

Base Cards 1 The First Doctor 34 Judoon 67 Dragonfire 2 The Second Doctor 35 The Family of Blood 68 Silver Nemesis 3 The Third Doctor 36 The Adipose 69 Ghost Light 4 The Fourth Doctor 37 Vashta 70 The End of the World 5 The Fifth Doctor 38 Tritovores 71 Aliens of London 6 The Sixth Doctor 39 Prisoner Zero 72 Dalek 7 The Seventh Doctor 40 The Tenza 73 The Parting of the Ways 8 The Eighth Doctor 41 The Silence 74 School Reunion 9 The War Doctor 42 The Wooden King 75 The Impossible Planet 10 The Ninth Doctor 43 The Great Intelligence 76 "42" 11 The Tenth Doctor 44 Ice Warrior Skaldak 77 Utopia 12 The Eleventh Doctor 45 Strax 78 Planet of the Ood 13 The Twelfth Doctor 46 Slitheen 79 The Sontaran Stratagem 14 Susan 47 Zygons 80 The Doctor's Daughter 15 Zoe 48 Sycorax 81 Midnight 16 Sarah Jane 49 The Master 82 Journey's End 17 Ace 50 Missy 83 The Waters of Mars 18 Rose 51 The Daleks 84 Victory of the Daleks 19 Captain Jack 52 The Sensorites 85 The Pandorica Opens 20 Martha 53 The Dalek Invasion of Earth 86 Closing Time 21 Donna 54 Tomb of the Cybermen 87 A Town Called Mercy 22 Amy 55 The Invasion 88 The Power of Three 23 Rory 56 The Claws of Axos 89 The Rings of Akhaten 24 Clara 57 Frontier in Space 90 The Night of the Doctor 25 Osgood 58 The Time Warrior 91 The Time of the Doctor 26 River 59 Death to the Daleks 92 Into the Dalek 27 Davros 60 Pyramids of Mars 93 Time Heist 28 Rassilon 61 The Keeper of Traken 94 In the Forest of the Night 29 The Ood 62 The Five Doctors 95 Before the Flood 30 The Weeping Angels 63 Resurrection of the Daleks 96