The Penobskan Porcupine Panic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Back Listeners: Locating Nostalgia, Domesticity and Shared Listening Practices in Contemporary Horror Podcasting

Welcome back listeners: locating nostalgia, domesticity and shared listening practices in Contemporary horror podcasting. Danielle Hancock (BA, MA) The University of East Anglia School of American Media and Arts A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2018 Contents Acknowledgements Page 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? Pages 3-29 Section One: Remediating the Horror Podcast Pages 49-88 Case Study Part One Pages 89 -99 Section Two: The Evolution and Revival of the Audio-Horror Host. Pages 100-138 Case Study Part Two Pages 139-148 Section Three: From Imagination to Enactment: Digital Community and Collaboration in Horror Podcast Audience Cultures Pages 149-167 Case Study Part Three Pages 168-183 Section Four: Audience Presence, Collaboration and Community in Horror Podcast Theatre. Pages 184-201 Case Study Part Four Pages 202-217 Conclusion: Considering the Past and Future of Horror Podcasting Pages 218-225 Works Cited Pages 226-236 1 Acknowledgements With many thanks to Professors Richard Hand and Mark Jancovich, for their wisdom, patience and kindness in supervising this project, and to the University of East Anglia for their generous funding of this project. 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? The origin of this thesis is, like many others before it, born from a sense of disjuncture between what I heard about something, and what I experienced of it. The ‘something’ in question is what is increasingly, and I believe somewhat erroneously, termed as ‘new audio culture’. By this I refer to all scholarly and popular talk and activity concerning iPods, MP3s, headphones, and podcasts: everything which we may understand as being tethered to an older history of audio-media, yet which is more often defined almost exclusively by its digital parameters. -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

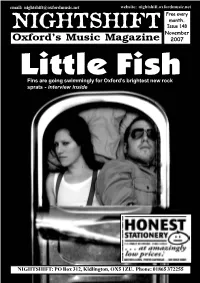

Issue 148.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

Tennyson's Poems

Tennyson’s Poems New Textual Parallels R. H. WINNICK To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. TENNYSON’S POEMS: NEW TEXTUAL PARALLELS Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels R. H. Winnick https://www.openbookpublishers.com Copyright © 2019 by R. H. Winnick This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work; to adapt the work and to make commercial use of the work provided that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way which suggests that the author endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: R. H. Winnick, Tennyson’s Poems: New Textual Parallels. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2019. https://doi.org/10.11647/OBP.0161 In order to access detailed and updated information on the license, please visit https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#copyright Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Digital material and resources associated with this volume are available at https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/944#resources Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omission or error will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. -

ピーター・バラカン 2013 年 6 月 1 日放送 Sun Ra 特

ウィークエンド サンシャイン PLAYLIST ARCHIVE DJ:ピーター・バラカン 2013 年 6 月 1 日放送 Sun Ra 特集 ゲスト:湯浅 学 01. We Travel The Space Ways / Sun Ra & His Astro Infinity Arkestra // Greatest Hits: Easy Listening For Intergalatic Travel 02. Saturn / Sun Ra & His Solar Arkestra // Visits Planet Earth Interstellar Low Ways 03. Dig This Boogie / Wynonie Harris with Jumpin' Jimmy Jackson Band // The Eternal Myth Revealed, Vol.1 04. Message to Earth Man / Yochanan, Sun Ra And The Arkestra // The Singles 05. MU / Sun Ra & His Astro Infinity Arkestra / Atlantis 06. The Design-Cosmos II / Sun Ra & His Astro Infinity Arkestra // My Brother The Wind Volume II 07. The Perfect Man / Sun Ra And His Astro Galactic Infinity Arkestra // The Singles 08. Gods of The Thunder Realm / Sun Ra And His Arkestra // Live At Montreux 09. Rocket#9 / Sun Ra // Space Is The Place 10. Dancing In The Sun / Sun Ra & His Solar Arkestra // The Heliocentric Worlds Of Sun Ra Vol.1 11. Take The A Train / Sun Ra Arkestra // Sunrise In Different Dimensions 12. The Old Man Of The Mountain / Phil Alvin // Phil Alvin Un "Sung Stories" 13. Love In Outer Space / Sun Ra // Purple Night 14. Lanquidity / Sun Ra // Lanquidity 2013 年 6 月 8 日放送 01. You're My Kind Of Climate (Party Mix) / Rip Rig & Panic // Methods Of Dance Volume 2 02. Bold As Love / Jimi Hendrix // The Jimi Hendrix Experience: Box Set 03. Who'll Stop The Rain / John Fogerty with Bob Seger // Wrote A Song For Everyone 04. Fortunate Son / John Fogerty with Foo Fighters // Wrote A Song For Everyone 05. -

The Odyssey, Book One 273 the ODYSSEY

05_273-611_Homer 2/Aesop 7/10/00 1:25 PM Page 273 HOMER / The Odyssey, Book One 273 THE ODYSSEY Translated by Robert Fitzgerald The ten-year war waged by the Greeks against Troy, culminating in the overthrow of the city, is now itself ten years in the past. Helen, whose flight to Troy with the Trojan prince Paris had prompted the Greek expedition to seek revenge and reclaim her, is now home in Sparta, living harmoniously once more with her husband Meneláos (Menelaus). His brother Agamémnon, commander in chief of the Greek forces, was murdered on his return from the war by his wife and her paramour. Of the Greek chieftains who have survived both the war and the perilous homeward voyage, all have returned except Odysseus, the crafty and astute ruler of Ithaka (Ithaca), an island in the Ionian Sea off western Greece. Since he is presumed dead, suitors from Ithaka and other regions have overrun his house, paying court to his attractive wife Penélopê, endangering the position of his son, Telémakhos (Telemachus), corrupting many of the servants, and literally eating up Odysseus’ estate. Penélopê has stalled for time but is finding it increasingly difficult to deny the suitors’ demands that she marry one of them; Telémakhos, who is just approaching young manhood, is becom- ing actively resentful of the indignities suffered by his household. Many persons and places in the Odyssey are best known to readers by their Latinized names, such as Telemachus. The present translator has used forms (Telémakhos) closer to the Greek spelling and pronunciation. -

Virginia Woolf, Hd, Germaine Dulac, and Walter Benjamin

LYRIC NARRATIVE IN LATE MODERNISM: VIRGINIA WOOLF, H.D., GERMAINE DULAC, AND WALTER BENJAMIN DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Cheryl Lynn Hindrichs, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Professor Sebastian Knowles, Adviser Approved by Professor Brian McHale ______________________________ Professor James Phelan Adviser Graduate Program in English ABSTRACT This dissertation redefines lyric narrative—forms of narration that fuse the associative resonance of lyric with the linear progression of narrative—as both an aesthetic mode and a strategy for responding ethically to the political challenges of the period of late modernism. Underscoring the vital role of lyric narrative as a late- modernist technique, I focus on its use during the period 1925-1945 by British writer Virginia Woolf, American expatriate poet H.D., French filmmaker Germaine Dulac, and German critic Walter Benjamin. Locating themselves as outsiders free to move across generic and national boundaries, each insisted on the importance of a dialectical vision: that is, holding in a productive tension the timeless vision of the lyric mode and the dynamic energy of narrative progression. Further, I argue that a transdisciplinary, feminist impulse informed this experimentation, leading these authors to incorporate innovations in fiction, music, cinema, and psychoanalysis. Consequently, I combine a narratological and historicist approach to reveal parallel evolutions of lyric narrative across disciplines—fiction, criticism, and film. Through an interpretive lens that uses rhetorical theory to attend to the ethical dimensions of their aesthetics, I show how Woolf’s, H.D.’s, Dulac’s, and Benjamin’s lyric narratives create unique relationships with their audiences. -

Download Black Freedom Beyond Borders Here!

Black Freedom Beyond Borders: Re-imagining Gender in Wakanda i Published in the United States 2019 by Wakanda Dream Lab x Resonance Network. Wakanda Dream Lab is a collective fan driven project that bridges the worlds of Black fandom and #Blacktivism for Black Liberation. It functions according to a value of emergence and celebrates the organic self-organizing nature of fandom. We intend to build on the aesthetics and pop culture appeal of Wakanda to develop a vision, principles, values and framework for prefigurative organizing of a new base of activists, artists and fans for Black Liberation. We believe that Black Liberation begets liberation of all peoples. Resonance Network is a community of people who share a deep belief that a world of interdependent thriving for all people, where violence is not the norm is possible. Network members work collectively to create strategies needed to interrupt the root causes of violence which are disproportionately affecting girls, women, and gender oppressed people; create the conditions needed for communities to be thriving, just, and accountable; and center the power and needs of people and communities who disproportionately experience the impacts of historic and current systems of oppression. All images used under the Creative Commons Share Alike license: https://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by-sa/4.0/ legalcode. This publication is covered by the Creative Commons No Derivatives license reserved by Wakanda Dream Lab https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd/4.0/. All written works remain the property of their respective authors, licensed for use by Wakanda Dream Lab x Resonance Network for this publication, other media, and promotional purposes. -

Color : Universal Language and Dictionary of Names

cam U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Universal Language and National Bureau of Standards Dictionary of Names NBS SPECIAL PUBLICATION 440 A111D3 D&77&H '^milSmif & TECH RI.C. A1 1 1 03087784 / 1 Standaras National Bureau of ^87? ftPR 19 C COLOR Q_ Universal Language and Dictionary of Names Kenneth L. Kelly and Deane B. Judd* Sensorv' Environment Section Center for Building Technology National Bureau of Standards Supersedes and Combines THE ISCC-NBS METHOD OF DESIGNATING COLORS AND A DICTIONARY OF COLOR NAMES, by Kenneth L. Kelly and Deane B. Judd, NBS Circular 553, Nov. 1, 1955 and A UNIVERSAL COLOR LANGUAGE, by Kenneth L. Kelly, Color Engineering 3, 16 (March-April 1965) Deceased U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, Elliot L. Richardson, Secretary Edward O. Vetter, Under Secretary Dr. Betsy Anker-Johnson, Assistant Secretary for Science and Technology J .National Bureau of Standards, Ernest Ambler, Acting Director DECEMBER 1976 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-600071 COVER PICTURE: Color solid representing the three-dimensional arrangement of colors. See also page A-2. Nat. Bur. Stand. (U.S.), Spec. Publ. 440, 184 pages (December 1976). For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 (Order by SD Catalog No. C13. 10 : 440) Price $3.25 Stock Number 003-003-01705-1 A-ii " NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. -

COLOR Q Universal Language and Dictionary of Names

cam U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE Universal Language and National Bureau of Standards Dictionary of Names NBS SPECIAL PUBLICATION 440 A111D3 D&77&H '^milSmif & TECH RI.C. A1 1 1 03087784 / 1 Standaras National Bureau of ^87? ftPR 19 C COLOR Q_ Universal Language and Dictionary of Names Kenneth L. Kelly and Deane B. Judd* Sensorv' Environment Section Center for Building Technology National Bureau of Standards Supersedes and Combines THE ISCC-NBS METHOD OF DESIGNATING COLORS AND A DICTIONARY OF COLOR NAMES, by Kenneth L. Kelly and Deane B. Judd, NBS Circular 553, Nov. 1, 1955 and A UNIVERSAL COLOR LANGUAGE, by Kenneth L. Kelly, Color Engineering 3, 16 (March-April 1965) Deceased U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE, Elliot L. Richardson, Secretary Edward O. Vetter, Under Secretary Dr. Betsy Anker-Johnson, Assistant Secretary for Science and Technology J .National Bureau of Standards, Ernest Ambler, Acting Director DECEMBER 1976 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 76-600071 COVER PICTURE: Color solid representing the three-dimensional arrangement of colors. See also page A-2. Nat. Bur. Stand. (U.S.), Spec. Publ. 440, 184 pages (December 1976). For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402 (Order by SD Catalog No. C13. 10 : 440) Price $3.25 Stock Number 003-003-01705-1 A-ii " NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act of Congress March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. -

Percy Bysshe Shelley - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Percy Bysshe Shelley - poems - Publication Date: 2004 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Percy Bysshe Shelley(1792-1822) Shelley, born the heir to rich estates and the son of an Member of Parliament, went to University College, Oxford in 1810, but in March of the following year he and a friend, Thomas Jefferson Hogg, were both expelled for the suspected authorship of a pamphlet entitled The Necessity of Atheism. In 1811 he met and eloped to Edinburgh with Harriet Westbrook and, one year later, went with her and her older sister first to Dublin, then to Devon and North Wales, where they stayed for six months into 1813. However, by 1814, and with the birth of two children, their marriage had collapsed and Shelley eloped once again, this time with Mary Godwin. Along with Mary's step-sister, the couple travelled to France, Switzerland and Germany before returning to London where he took a house with Mary on the edge of Great Windsor Park and wrote Alastor (1816), the poem that first brought him fame. In 1816 Shelley spent the summer on Lake Geneva with Byron and Mary who had begun work on her Frankenstein. In the autumn of that year Harriet drowned herself in the Serpentine in Hyde Park and Shelley then married Mary and settled with her, in 1817, at Great Marlow, on the Thames. They later travelled to Italy, where Shelley wrote the sonnet Ozymandias (written 1818) and translated Plato's Symposium from the Greek. Shelley himself drowned in a sailing accident in 1822. -

Notion of Victory: a Theory And

CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY CRANFIELD DEFENCE AND SECURITY DEPARTMENT OF APPLIED SCIENCE, SECURITY AND RESILIENCE PhD Thesis Academic Year 2008 – 2009 Brigadier Mohammad Iftikhar Zaidi THE CONDUCT OF WAR AND THE NOTION OF VICTORY: A THEORY AND DEFINITION OF VICTORY Supervisor: Professor Christopher D. Bellamy August 2009 This thesis is submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for Doctorate of Philosophy. © Cranfield University 2009, all rights reserved. No part if this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright holder. ~i~ ~ii~ ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS It was an honour and a privilege to be part of the Cranfield Defence and Security research community. I have the most profound admiration for all those directly or indirectly associated with my research for their support and guidance that was essential for steering me through the many challenges I confronted. First and foremost I wish to acknowledge Prof. Christopher Bellamy, my research supervisor, for the encouragement, guidance and direction I enjoyed from the very beginning through to the culmination of this research; Dr Laura Cleary, the research director, for her astute advice and continuous support and of course, a special mention of Prof. Richard Holmes, who has been a major inspiration throughout my academic pursuits. Cranfield University provided the most congenial environment for research. I had the opportunity to interact with many bright minds; not all find a mention here but are acknowledged most humbly for enriching my research and making my stay pleasant. The support team at the Security Studies Institute deserves a separate mention. The entire administrative team which was initially headed by Steph Muir and later Anne Harbour were more than forthcoming in providing all kinds of assistance and, on many occasions, going out of their way.