Notion of Victory: a Theory And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Back Listeners: Locating Nostalgia, Domesticity and Shared Listening Practices in Contemporary Horror Podcasting

Welcome back listeners: locating nostalgia, domesticity and shared listening practices in Contemporary horror podcasting. Danielle Hancock (BA, MA) The University of East Anglia School of American Media and Arts A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 2018 Contents Acknowledgements Page 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? Pages 3-29 Section One: Remediating the Horror Podcast Pages 49-88 Case Study Part One Pages 89 -99 Section Two: The Evolution and Revival of the Audio-Horror Host. Pages 100-138 Case Study Part Two Pages 139-148 Section Three: From Imagination to Enactment: Digital Community and Collaboration in Horror Podcast Audience Cultures Pages 149-167 Case Study Part Three Pages 168-183 Section Four: Audience Presence, Collaboration and Community in Horror Podcast Theatre. Pages 184-201 Case Study Part Four Pages 202-217 Conclusion: Considering the Past and Future of Horror Podcasting Pages 218-225 Works Cited Pages 226-236 1 Acknowledgements With many thanks to Professors Richard Hand and Mark Jancovich, for their wisdom, patience and kindness in supervising this project, and to the University of East Anglia for their generous funding of this project. 2 Introduction: Why Podcasts, Why Horror, and Why Now? The origin of this thesis is, like many others before it, born from a sense of disjuncture between what I heard about something, and what I experienced of it. The ‘something’ in question is what is increasingly, and I believe somewhat erroneously, termed as ‘new audio culture’. By this I refer to all scholarly and popular talk and activity concerning iPods, MP3s, headphones, and podcasts: everything which we may understand as being tethered to an older history of audio-media, yet which is more often defined almost exclusively by its digital parameters. -

Blitzkrieg: the Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht's

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Electronic Theses and Dissertations Student Works 8-2021 Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era Briggs Evans East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Evans, Briggs, "Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era" (2021). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 3927. https://dc.etsu.edu/etd/3927 This Thesis - unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era ________________________ A thesis presented to the faculty of the Department of History East Tennessee State University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History ______________________ by Briggs Evans August 2021 _____________________ Dr. Stephen Fritz, Chair Dr. Henry Antkiewicz Dr. Steve Nash Keywords: Blitzkrieg, doctrine, operational warfare, American military, Wehrmacht, Luftwaffe, World War II, Cold War, Soviet Union, Operation Desert Storm, AirLand Battle, Combined Arms Theory, mobile warfare, maneuver warfare. ABSTRACT Blitzkrieg: The Evolution of Modern Warfare and the Wehrmacht’s Impact on American Military Doctrine during the Cold War Era by Briggs Evans The evolution of United States military doctrine was heavily influenced by the Wehrmacht and their early Blitzkrieg campaigns during World War II. -

THE BRITISH ARMY in the LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 By

‘FAIRLY OUT-GENERALLED AND DISGRACEFULLY BEATEN’: THE BRITISH ARMY IN THE LOW COUNTRIES, 1793-1814 by ANDREW ROBERT LIMM A thesis submitted to the University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY. University of Birmingham School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law October, 2014. University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT The history of the British Army in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars is generally associated with stories of British military victory and the campaigns of the Duke of Wellington. An intrinsic aspect of the historiography is the argument that, following British defeat in the Low Countries in 1795, the Army was transformed by the military reforms of His Royal Highness, Frederick Duke of York. This thesis provides a critical appraisal of the reform process with reference to the organisation, structure, ethos and learning capabilities of the British Army and evaluates the impact of the reforms upon British military performance in the Low Countries, in the period 1793 to 1814, via a series of narrative reconstructions. This thesis directly challenges the transformation argument and provides a re-evaluation of British military competency in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. -

The Philosophy of War and Peace

THE PHILOSOPHY OF WAR AND PEACE Oleg Bazaluk1 — Doctor of Philosophy, Professor, Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi State Pedagogical University (Pereiaslav-Khmelnytskyi, Ukraine) E-mail: [email protected] Tamara Blazhevych2 — Senior lecturer, Kyiv University of Tourism, Economy, and Law (Kyiv, Ukraine) E-mail: [email protected] In the paper the author comprehends ontology of the war and peace. Using the results of empiri- cal and theoretical research in the field of geophilosophy, as well as neuroscience, psychology, social philosophy and military history, the author comprehends the philosophy of war and peace. The author proves that the problem of war and peace originates in the features of forming men- tality. War and peace are the ways to achieve a regulatory compromise between manifestations of the active principle, which was initially laid in the foundation of the human mentality, and the influence of the external environment through natural selection; between the complicating needs of mental space as a totality of mentalities at the scale of the Earth and the possibilities of satisfying them; between the proclaimed idea that unites mental space, and the possibility of its implementa- tion. War and Peace regulate high-quality structure and manifestations of mental space: reduce the number of mentalities, whose structures predispose to aggression, and increase the number of men- talities, whose manifestations are directed at integration and cooperation. Through the proposed theory of war and peace, I have come to realize that, the state of peace for the evolving mental space includes the philosophy of war; the transition from peace to war depends mainly on the effective- ness of educational technology. -

Downbeat.Com December 2014 U.K. £3.50

£3.50 £3.50 . U.K DECEMBER 2014 DOWNBEAT.COM D O W N B E AT 79TH ANNUAL READERS POLL WINNERS | MIGUEL ZENÓN | CHICK COREA | PAT METHENY | DIANA KRALL DECEMBER 2014 DECEMBER 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Žaneta Čuntová Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Associate Kevin R. Maher Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, -

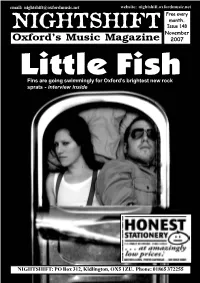

Issue 148.Pmd

email: [email protected] website: nightshift.oxfordmusic.net Free every month. NIGHTSHIFT Issue 148 November Oxford’s Music Magazine 2007 Little Fish Fins are going swimmingly for Oxford’s brightest new rock sprats - interview inside NIGHTSHIFT: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU. Phone: 01865 372255 NEWNEWSS Nightshift: PO Box 312, Kidlington, OX5 1ZU Phone: 01865 372255 email: [email protected] AS HAS BEEN WIDELY Oxford, with sold-out shows by the REPORTED, RADIOHEAD likes of Witches, Half Rabbits and a released their new album, `In special Selectasound show at the Rainbows’ as a download-only Bullingdon featuring Jaberwok and album last month with fans able to Mr Shaodow. The Castle show, pay what they wanted for the entitled ‘The Small World Party’, abum. With virtually no advance organised by local Oxjam co- press or interviews to promote the ordinator Kevin Jenkins, starts at album, `In Rainbows’ was reported midday with a set from Sol Samba to have sold over 1,500,000 copies as well as buskers and street CSS return to Oxford on Tuesday 11th December with a show at the in its first week. performers. In the afternoon there is Oxford Academy, as part of a short UK tour. The Brazilian elctro-pop Nightshift readers might remember a fashion show and auction featuring stars are joined by the wonderful Metronomy (recent support to Foals) that in March this year local act clothes from Oxfam shops, with the and Joe Lean and the Jing Jang Jong. Tickets are on sale now, priced The Sad Song Co. - the prog-rock main concert at 7pm featuring sets £15, from 0844 477 2000 or online from wegottickets.com solo project of Dive Dive drummer from Cyberscribes, Mr Shaodow, Nigel Powell - offered a similar deal Brickwork Lizards and more. -

Eugene Miakinkov

Russian Military Culture during the Reigns of Catherine II and Paul I, 1762-1801 by Eugene Miakinkov A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©Eugene Miakinkov, 2015 Abstract This study explores the shape and development of military culture during the reign of Catherine II. Next to the institutions of the autocracy and the Orthodox Church, the military occupied the most important position in imperial Russia, especially in the eighteenth century. Rather than analyzing the military as an institution or a fighting force, this dissertation uses the tools of cultural history to explore its attitudes, values, aspirations, tensions, and beliefs. Patronage and education served to introduce a generation of young nobles to the world of the military culture, and expose it to its values of respect, hierarchy, subordination, but also the importance of professional knowledge. Merit is a crucial component in any military, and Catherine’s military culture had to resolve the tensions between the idea of meritocracy and seniority. All of the above ideas and dilemmas were expressed in a number of military texts that began to appear during Catherine’s reign. It was during that time that the military culture acquired the cultural, political, and intellectual space to develop – a space I label the “military public sphere”. This development was most clearly evident in the publication, by Russian authors, of a range of military literature for the first time in this era. The military culture was also reflected in the symbolic means used by the senior commanders to convey and reinforce its values in the army. -

Bali for the World : Qu'est-Ce Que Bali Peut Offrir

N°140 : janvier 2017 Le média francophone d’Indonésie | www.lagazettedebali.info Pierre Porte & Partners « Mostly Jazz » Lila Bodor Désiré Charnay Alain Riquier Jean-Paul Decrock Lemon Nails BARC « Charcoal for Children » Dikna Faradiba Putu Louis Compostel PSG Bali Academy Championnat du monde de Pencak Silat Moana Al Diwan « Marlina Si Pembunuh Dalam Empat Babak » BALI FOR THE WORLD : QU’EST-CE QUE BALI PEUT OFFRIR AU RESTE DU MONDE ? © Socrate Georgiades index epanouissement BALI FOR THE WORLD : QU’EST-CE QUE BALI PEUT OFFRIR AU RESTE DU MONDE ? 4-5 business PIERRE PORTE : LA CONSTRUCTION DE MAISONS- CONTAINERS EST A 50% DU PRIX DU MARCHE NORMAL 10 NATIONAL LE GOUVERNEMENT A-T-IL DEJOUE UNE TENTATIVE DE RENVERSEMENT ? 25 MEDIA KELAS INTERNASIONAL : UN PEU DE RACISME ORDINAIRE MAIS C’EST POUR RIRE 26 CUISINE • AL DIWAN : J’AI EU ENVIE DE ME FABRIQUER MON PETIT LIBAN A MOI • MOANA, LA CUISINE TAHITIENNE SUR BATU BOLONG 30 édito LECHE-VITRINES On doit rarement chercher dans l’actualité des raisons de se réjouir. Et en ce moment, encore moins. EN 2017, A BALI, ON VA FAIRE DU Pour préserver un peu la quiétude de notre vie balinaise, nous avons décidé de bannir de notre fil SURF NUS SUR LES VOLCANS, SI, SI... d’actualité de Facebook ce qu’on appelle dans notre jargon les « hard news », toute la noirceur de l’actualité que vous pourrez lire désormais si vous le souhaitez sur notre compte Twitter. 34 Nous vivons une époque troublée mais il faut continuer à garder le sourire et l’espoir préparer nos enfants pour l’avenir, continuer à entreprendre et à être attentif à nos proches. -

Spring 2012 CAS Department of Philosophy Undergraduate Courses

01/20/2012 Spring 2012 CAS Department of Philosophy Undergraduate Courses http://www.philosophy.buffalo.edu/courses PHI 101 BEE Intro. to Philosophy Beebe, J M 6:00pm - 8:40pm Cooke 121 13444 This course will introduce students to some of the basic questions and methods of philosophy. We will begin by looking at the birth of Western philosophy in ancient Greece. We will read three of Plato's dialogues and will learn about the life of Socrates, the first great Western philosopher. We will then wrestle with philosophical questions such as the following: What must one do to be truly happy? Are there absolute truths? Is truth relative? Is it ethically permissible to clone human beings? Is euthanasia morally permissible? How is the mind related to the brain? Is it anything more than the brain? Can computers think? Do humans have free will? If so, what is the nature of that freedom? Is it rational to believe in God? Is the existence of evil incompatible with the existence of a wholly good God? PHI 101 CHO Intro. to Philosophy Cho, K MWF 9:00am-9:50am O’Brian 109 15620 In addition to discussing the standardized introductory topics such as Reality, Knowledge, Ethics, Religion, Art, Mind and Body, based on the works of classical Western philosophers, the course is designed to make ourselves to be more critically inquisitive about what we normally take (in the Western world) for granted. For this purpose, a second textbook with sources from John Dewey and Confucius, is selected. Required texts: 1. R. Solomon, Introducing Philosophy, 10th edition, Oxford University Press. -

The Philosophy of Loyalty

29 The Philosophy of Loyalty I. The Nature and the Need of Loyalty One of the most familiar traits of our time is the tendency to revise tradition, to reconsider the foundations of old beliefs, and some times mercilessly to destroy what once seemed indispensable. This disposition, as we all know, is especially prominent in the realms of social theory and of religious belief. But even the exact sciences do not escape from the influence of those who are fond of the reexamination of dogmas. And the modern tendency in question has, of late years, been very notable in the field of Ethics. Conven tional morality has been required, in company with religion, and also in company with exact science, to endure the fire of criticism. And although, in all ages, the moral law has indeed been exposed to the assaults of the wayward, the peculiar moral situation of our time is this, that it is no longer either the flippant or the vicious who are the most pronounced or the most dangerous opponents of our moral traditions. Devoted reformers, earnest public servants, ardent prophets of a coming spiritual order,-all these types of lovers of humanity are represented amongst those who to-day demand great and deep changes in the moral standards by which our lives are [The complete text of The P!Jilosopby of Loyalty is reprinted here from PL.] 8 )6 MORAL AND RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE to be governed. We have become accustomed, during the past few generations,-during the period of Socialism and of Individualism, of Karl Marx, of Henry George, of Ibsen, of Nietzsche, of Tolstoi, -to hear unquestionably sincere lovers of humanity sometimes de claring our traditions regarding the rights of property to be im moral, and sometimes assailing, in the name of virtue, our present family ties as essentially unworthy of the highest ideals. -

The Southeast Asia Union Messenger for September 1, 1977

southeast asia September-October, 1977, M. C. (P) No.111 124/1/7711b 4 14111 • Da ^P.! John Hancock, with animated accordian, Winston De Haven and juvenile Pathfinders engage in action songs. "Phew! It's hot!" So thought all the pathfinders on Saturday September 17 as they assembled for inspection on the quadrangle at Southeast Asia Union College. This was Pathfinder Day, an event held around the world in September of each year. It was a time of fun, fellowship, and formalities. Thirteen Pathfinders were invested as Master Guides during the afternoon meeting. Pastor John Hancock gave the message and together with Pastor Winston De Haven, [Continued on page 10.] aziWeser 1978 - Lay Evangelism Year Published bi-monthly as the official organ of the South- east Asia Union Mission of Seventh-day Adventists, 251 Upper Serangoon Road, Singapore, 13. Yearly Subscription Price S2.50 (U.S.) Editor Jill Warden Parchment By W. L. Wilcox, President Circulation Manager Esther Donato Southeast Asia Union Mission "Contributing Editors" throughodt our Union field are: MISSIONS: Sabah Miss. Hon Yin Kong Sarawak Pastor Paull Dixon The Southeast Asia Union Mission committee recently voted Thailand Mrs. Art Bell W. Malaysia-Singapore Pastor T. K. Chong that 1978 would be proclaimed "Lay Evangelism Year." This is a very timely action. Never before in the history of the world INSTITUTIONS: have so many signs so strikingly revealed the fact that the Southeast Asia Union College Mrs. Maggie Tan Bangkok Adventist Hospital . Mrs. Loretta Alspaugh coming of Jesus is indeed very near. Head Yai Mission Hospital Mrs. Art Elumir Penang Adventist Hospital Mr. -

Training to Fight – Russia's Major Military Exercises 2011–2014

“Train hard, fi ght easy.” The Russian 18th century General Aleksandr Norberg Johan toFight Training Vasilievich Suvorov (see cover) is said to never have lost a battle. The main idea of his dictum is clear. Armed forces train to fi ght. The more they train, the better they get. Exercises are primarily a way to develop capabilities in units, build the fi ghting power of a force and, ultimately, the military power of the state. How did military exercises contribute to the fi ghting power of Russia’s Armed Forces in 2011 – 2014? Based on reporting in Russian open sources, the main conclusion in this report is that the Russian Armed Forces exercises enabled them to train how to launch and fi ght large-scale joint inter-service operations, i.e. launching and waging inter-state wars Training to Fight – Russia’s Major Military Exercises 2011–2014 Johan Norberg FOI-R--4128--SE ISSN1650-1942 www.foi.se December 2015 Johan Norberg Training to Fight – Russia’s Major Military Exercises 2011–2014 Press Bild/Cover: TT/The Art Collector/Heritage. Alexander Suvorov, Russian general, (1833). In a military career lasting almost 60 years, Suvorov (1729-1800) never lost a battle. In 1799-1800, during the War of the Second Coalition against France, he led a Russian army on an epic retreat across the Alps reminiscent of Hannibal. Found in the collection of The Hermitage, St Petersburg. FOI-R--4128--SE Titel Training to Fight Title Training to Fight Rapportnr/Report no FOI-R--4128--SE Månad/Month December Utgivningsår/Year 2015 Antal sidor/Pages 100 ISSN 1650-1942 Kund/Customer Försvarsdepartementet / Swedish Ministry of Defence Forskningsområde 8.