THE EARLY ATTEMPTS on MONT BLANC DE COURMAYEUR from the INNOMINATA BASIN • (Continued.)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

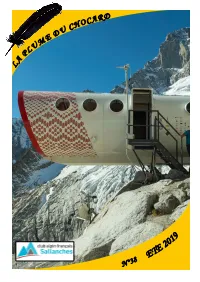

REFUGE BIVOUAC GERVASUTTI S’Aperçoit Tel Un Point Rouge Tout Là-Haut

ÉTÉ 2019 2 Numéro 38 LE MOT DU PRESIDENT Bonjour à tous, Après une saison hivernale en de- mi-teinte vous êtes sans doute impatients de profiter de la nouvelle saison. La Plume du Chocard, avec son programme varié, fera, nous l’espérons, sinon le bonheur de tous, à tout le moins donnera satisfaction au plus grand nombre. L’école de ski, malgré un début de saison qui s’annonçait difficile faute de neige a permis une fois de plus aux nom- breux jeunes et moins jeunes de réussir les tests ESF et n’en doutons pas, tous ont progressé en se faisant plaisir. Merci et bravo à l’équipe des encadrants, ils ont accueilli gentiment leurs nouveaux collègues. En effet ils sont quatre nouveaux moniteurs FFCAM qui ont réussi brillamment l’examen cet hiver, je les félicite au nom de tous. L’école d’escalade poursuit son bonhomme de chemin avec toujours autant d’inscrits. Le Groupe Performance s’est distingué dans les compétitions nombreuses où ils ont porté haut les couleurs du CAF de Sallanches. Bravo à nos jeunes grimpeurs et à leur entraineur Olivier Daligault. Je ne parle pas de toutes les activités c’est un édito !! Mais je remercie tous les enca- drants et participants qui ont largement contribué à la vie de notre club qui est sans doute un des meilleurs de la vallée. En parlant des six autres CAF de la haute vallée de l’Arve nous nous rencontrons régulière- ment et nous proposons à tous les adhérents des soirées à thème ou des formations organisées localement. -

Le Mt Blanc Journée Beaufortain

Journée BEAUFORTAIN et ITALIE www.terreinconnue.fr tél: 03 87 38 75 49 MEGÈVE, le top du chic LES SAISIES , Megève est certainement l’Espace Diamant la plus mondaine des SAINT-GERVAIS , A 1650 m d’altitude, stations alpines françaises. station Alti-Forme dans le Beaufortain, Son important essor C’est sur le territoire même de cette station est aussi touristique remonte à 1910 Saint-Gervais que se dressent les appelée le « Tyrol lorsque la famille 4810 m du Mont-Blanc. Français ». La vue Rothschild décida d’en Les eaux de Saint-Gervais sont panoramique sur le faire son lieu de villégiature célèbres depuis près de 2 siècles Mont-Blanc est pour concurrencer Saint- pour la dermatologie et le saisissante. Moritz en Suisse. traitement des voies respiratoires. Le Beaufortain, le massif comme un jardin ! Avec ses alpages constellés de chalets, ses torrents fougueux et ses grands lacs, le Beaufortain ressemble à un jardin d’éden. Entrez dans ce royaume préservé dont les habitants ont sauvegardé les pâturages et refusé le béton. Le barrage de Roselend avec ses 185 millions de m3 d’eau constitue une richesse hydraulique. Col du Petit-Saint-Bernard COURMAYEUR C’est un col alpin qui sépare la Courmayeur est situé au pied du Tarentaise, c’est-à-dire la vallée de massif du Mont-Blanc. l’Isère, de la vallée d’Aoste. Son Le Mont-Blanc est situé sur sa altitude, 2188m, en fait le col le moins commune. Le tracé de la élévé de la région. Il a été fréquenté frontière franco-italienne est depuis la plus haute Antiquité. -

Note on the History of the Innominata Face of Mont Blanc De Courmayeur

1 34 HISTORY OF THE INNOMINATA FACE them difficult but solved the problem by the most exposed, airy and exhilarating ice-climb I ever did. I reckon sixteen essentially different ways to Mont Blanc. I wish I had done them all ! NOTE ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS FIG. 1. This was taken from the inner end of Col Eccles in 1921 during the ascent of Mont Blanc by Eccles' route. Pie Eccles is seen high on the right, and the top of the Aiguille Noite de Peteret just shows over the left flank of the Pie. FIG. 2. This was taken from the lnnominata face in 1919 during a halt at 13.30 on the crest of the branch rib. The skyline shows the Aiguille Blanche de Peteret on the extreme left (a snow cap), with Punta Gugliermina at the right end of what appears to be a level summit ridge but really descends steeply. On the right of the deep gap is the Aiguille Noire de Peteret with the middle section of the Fresney glacier below it. The snow-sprinkled rock mass in the right lower corner is Pie Eccles a bird's eye view. FIG. 3. This was taken at the same time as Fig. 2, with which it joins. Pie Eccles is again seen, in the left lower corner. To the right of it, in the middle of the view, is a n ear part of the branch rib, and above that is seen a bird's view of the Punta lnnominata with the Aiguille Joseph Croux further off to the left. -

4000 M Peaks of the Alps Normal and Classic Routes

rock&ice 3 4000 m Peaks of the Alps Normal and classic routes idea Montagna editoria e alpinismo Rock&Ice l 4000m Peaks of the Alps l Contents CONTENTS FIVE • • 51a Normal Route to Punta Giordani 257 WEISSHORN AND MATTERHORN ALPS 175 • 52a Normal Route to the Vincent Pyramid 259 • Preface 5 12 Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey 101 35 Dent d’Hérens 180 • 52b Punta Giordani-Vincent Pyramid 261 • Introduction 6 • 12 North Face Right 102 • 35a Normal Route 181 Traverse • Geogrpahic location 14 13 Gran Pilier d’Angle 108 • 35b Tiefmatten Ridge (West Ridge) 183 53 Schwarzhorn/Corno Nero 265 • Technical notes 16 • 13 South Face and Peuterey Ridge 109 36 Matterhorn 185 54 Ludwigshöhe 265 14 Mont Blanc de Courmayeur 114 • 36a Hörnli Ridge (Hörnligrat) 186 55 Parrotspitze 265 ONE • MASSIF DES ÉCRINS 23 • 14 Eccles Couloir and Peuterey Ridge 115 • 36b Lion Ridge 192 • 53-55 Traverse of the Three Peaks 266 1 Barre des Écrins 26 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable 117 37 Dent Blanche 198 56 Signalkuppe 269 • 1a Normal Route 27 15 L’Isolée 117 • 37 Normal Route via the Wandflue Ridge 199 57 Zumsteinspitze 269 • 1b Coolidge Couloir 30 16 Pointe Carmen 117 38 Bishorn 202 • 56-57 Normal Route to the Signalkuppe 270 2 Dôme de Neige des Écrins 32 17 Pointe Médiane 117 • 38 Normal Route 203 and the Zumsteinspitze • 2 Normal Route 32 18 Pointe Chaubert 117 39 Weisshorn 206 58 Dufourspitze 274 19 Corne du Diable 117 • 39 Normal Route 207 59 Nordend 274 TWO • GRAN PARADISO MASSIF 35 • 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable Traverse 118 40 Ober Gabelhorn 212 • 58a Normal Route to the Dufourspitze -

Lgnaz Venetz Aus Stalden {Wallis)

lgnaz Venetz lgnaz Venetz aus Stalden {Wallis) geb. am 27. März 1788 in Visperterminen gest. am 20. April 1859 in Sitten Walliser Kantonsingenieur von 1816 bis 1837 beratender Ingenieur in den Kantonen Waadt und Watris nach 1838 Mitbegründer der Vergletscherungstheorie Pflanzen- und Insektenforscher Preisträger der Schweizerischen . Naturforschenden Gesellschaft 1m Jahre 1822 mit der Schrift «Memoire sur les variations de Ia temperature dans les Alpes suisses» 1788-1859 I GE IEUR UD ATURFORSCHE Gedenkschrift Die Erstellung und Herausgabe dieses Buches haben finanziell unterstützt: Schweizerische Akademie der Naturwissenschaften Staat Wallis (Erziehungsdepartement) Kraftwerke Mattmark AG (Elektrowatt) Loterie romande (Delegation valaisanne) Berchtold Stefan, Geotechnik-Büro, Visp \ Gemeinde Stalden Naturforschende Gesellschaft Oberwallis MlGROS Wallis Kraftwerke Mauvoisin (Elektrowatt) LONZA AG (Sparte Energie) Walliser Elektrizitätsgesellschaft AG Schweizerische Bankgesellschaft, Visp Schweizerischer Bankverein, Visp Walliser Ersparniskasse, Visp Walliser Kantonalbank, Visp * * * Diese Gedenkschrift erscheint als Band Nr. 1 der Mitteilungen der Naturforschenden Gesellschaft Oberwallis (NGO gegründet 1979). * * * - Herausgeber: Naturforschende Gesellschaft Oberwallis (St. Berchtold, P. Bumann) - Gestaltung, Satz und Druck: Mengis Druck und Verlag, Visp - Verlag: © Rotten-Verlag AG, Brig 1990 - Titelbild: Eisschuttkegel des Glacier du Gietro Graphische Sammlung ETH Zürich, (Nr. 223 = lnv. C XII 13b); Dia zur Verfügung gestellt durch Musee -

One Hundred Years Ago C. A. Russell

88 Piz Bernilla, Ph Scerscell and Piz Roseg (Photo: Swiss atiollal TOl/rist Office) One hundred years ago (with extracts from the 'Alpine Journal') c. A. Russell The weather experienced in many parts of rhe Alps during rhe early months of 1877 was, to say the least, inhospitable. Long unsettled periods alternated with spells of extreme cold and biting winds; in the vicinity of St Morirz very low temperatures were recorded during January. One member of the Alpine Club able to make numerous high-level excur sions during the winter months in more agreeable conditions was D. W. Freshfield, who explored the Maritime Alps and foothills while staying at Cannes. Writing later in the AlpilJe Journal Freshfield recalled his _experiences in the coastal mountains, including an ascent above Grasse. 'A few steps to rhe right and I was on top of the Cheiron, under the lee of a big ruined signal, erected, no doubt, for trigonometrical purposes. It was late in the afternoon, and the sun was low in the western heavens. A wilder view I had never seen even from the greatest heights. The sky was already deepening to a red winter sunset. Clouds or mountains threw here and there dark shadows across earth and sea. "Far our at ea Corsica burst out of the black waves like an island in flames, reflecting the sunset from all its snows. From the sea-level only its mountain- 213 89 AiguiJle oire de Pelllerey (P!JOIO: C. Douglas Mill/er) 214 ONE HU DRED YEARS AGO topS, and these by aid of refraction, overcome the curvature of the globe. -

Les Clochers D'arpette

31 Les Clochers d’Arpette Portrait : large épaule rocheuse, ou tout du moins rocailleuse, de 2814 m à son point culminant. On trouve plusieurs points cotés sur la carte nationale, dont certains sont plus significatifs que d’autres. Quelqu’un a fixé une grande branche à l’avant-sommet est. Nom : en référence aux nombreux gendarmes rocheux recouvrant la montagne sur le Val d’Arpette et faisant penser à des clochers. Le nom provient surtout de deux grosses tours très lisses à 2500 m environ dans le versant sud-est (celui du Val d’Arpette). Dangers : fortes pentes, chutes de pierres et rochers à « varapper » Région : VS (massif du Mont Blanc), district d’Entremont, commune d’Orsières, Combe de Barmay et Val d’Arpette Accès : Martigny Martigny-Combe Les Valettes Champex Arpette Géologie : granites du massif cristallin externe du Mont Blanc Difficulté : il existe plusieurs itinéraires possibles, partant aussi bien d’Arpette que du versant opposé, mais il s’agit à chaque fois d’itinéraires fastidieux et demandant un pied sûr. La voie la plus courte et relativement pas compliquée consiste à remonter les pentes d’éboulis du versant sud-sud-ouest et ensuite de suivre l’arête sud-ouest exposée (cotation officielle : entre F et PD). Histoire : montagne parcourue depuis longtemps, sans doute par des chasseurs. L’arête est fut ouverte officiellement par Paul Beaumont et les guides François Fournier et Joseph Fournier le 04.09.1891. Le versant nord fut descendu à ski par Cédric Arnold et Christophe Darbellay le 13.01.1993. Spécificité : montagne sauvage, bien visible de la région de Fully et de ses environs, et donc offrant un beau panorama sur le district de Martigny, entre autres… 52 32 L’Aiguille d’Orny Portrait : aiguille rocheuse de 3150 m d’altitude, dotée d’aucun symbole, mais équipée d’un relais d’escalade. -

Escursioni a Courmayeur Val Veny • Val Ferret • Valdigne • La Thuille

collanasentierid’autore 11 Escursioni a Courmayeur Val Veny • Val Ferret • Valdigne • La Thuille idea Montagna editoria e alpinismo Sentieri d’autore l Escursioni a Courmayeur collanasentierid’autore Escursioni a Courmayeur idea Montagna editoria e alpinismo 2 l Introduzione INTRODUZIONE SEGUI IDEA MONTAGNA SU: Per secoli fu chiamato Mont Maudit, Mont Mallet, Mont Malay, nomi che incutevano timore e ri- www.facebook.com/ideamontagna spetto. Poi, conclusa l’esplorazione orizzontale del globo, il nuovo orizzonte si spostò in verticale plus.google.com/+IdeamontagnaIt e in piena età illuminista il monte maledetto divenne il Monte Bianco e la montagna, perduta la www.pinterest.com/ideamontagna componente malefica che l’aveva contraddistinta precedentemente, cominciò a essere guardata www.slideshare.net/IdeaMontagna con occhi nuovi, come una cima da studiare, osservare, ammirare ma soprattutto da scalare. Il primato dell’altezza, portò il Monte Bianco a essere il primo “4000” raggiunto, in una vera e propria corsa alla vetta che vide vincitori materialmente Jacques Balmat e Michel Paccard, ma che fu spinta e motivata soprattutto dal sincero trasporto di Horace Bénédicte De Saussure. L’8 agosto del 1786 è tradizionalmente considerata la data d’inizio dell’alpinismo contemporaneo. Oggi il Monte Bianco è un simbolo, un nome che evoca automaticamente il concetto di monta- gna, di vetta. Così facilmente osservabile dalle valli che lo circondano, il Bianco è diventato spes- FOTOGRAFIE so anche immagine stereotipata, come gran parte dei più spettacolari gruppi alpini. Una fitta rete Tutte le fotografie utilizzate sono dell’autore, dove non specificato in didascalia. di sentieri lascia spesso l’escursionista al di fuori della fortezza di roccia e ghiaccio del massiccio vero e proprio, quasi sempre accessibile soltanto agli alpinisti, ma allo stesso tempo permette di capire la complessità di questo gruppo montuoso, le tante sorprese, i paesaggi grandiosi e sorprendenti. -

Mountaineering Ventures

70fcvSs )UNTAINEERING Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 v Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto http://www.archive.org/details/mountaineeringveOObens 1 £1. =3 ^ '3 Kg V- * g-a 1 O o « IV* ^ MOUNTAINEERING VENTURES BY CLAUDE E. BENSON Ltd. LONDON : T. C. & E. C. JACK, 35 & 36 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.C. AND EDINBURGH PREFATORY NOTE This book of Mountaineering Ventures is written primarily not for the man of the peaks, but for the man of the level pavement. Certain technicalities and commonplaces of the sport have therefore been explained not once, but once and again as they occur in the various chapters. The intent is that any reader who may elect to cull the chapters as he lists may not find himself unpleasantly confronted with unfamiliar phraseology whereof there is no elucidation save through the exasperating medium of a glossary or a cross-reference. It must be noted that the percentage of fatal accidents recorded in the following pages far exceeds the actual average in proportion to ascents made, which indeed can only be reckoned in many places of decimals. The explanation is that this volume treats not of regular routes, tariffed and catalogued, but of Ventures—an entirely different matter. Were it within his powers, the compiler would wish ade- quately to express his thanks to the many kind friends who have assisted him with loans of books, photographs, good advice, and, more than all, by encouraging countenance. Failing this, he must resort to the miserably insufficient re- source of cataloguing their names alphabetically. -

Mer De Glace” (Mont Blanc Area, France) AD 1500–2050: an Interdisciplinary Approach Using New Historical Data and Neural Network Simulations

Zeitschrift für Gletscherkunde und Glazialgeologie Herausgegeben von MICHAEL KUHN BAND 40 (2005/2006) ISSN 0044-2836 UNIVERSITÄTSVERLAG WAGNER · INNSBRUCK 1907 wurde von Eduard Brückner in Wien der erste Band der Zeitschrift für Gletscherkunde, für Eiszeitforschung und Geschichte des Klimas fertig gestellt. Mit dem 16. Band über- nahm 1928 Raimund von Klebelsberg in Innsbruck die Herausgabe der Zeitschrift, deren 28. Band 1942 erschien. Nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg gab Klebelsberg die neue Zeitschrift für Gletscherkunde und Glazialgeologie im Universitätsverlag Wagner in Innsbruck heraus. Der erste Band erschien 1950. 1970 übernahmen Herfried Hoinkes und Hans Kinzl die Herausgeberschaft, von 1979 bis 2001 Gernot Patzelt und Michael Kuhn. In 1907 this Journal was founded by Eduard Brückner as Zeitschrift für Gletscherkunde, für Eiszeitforschung und Geschichte des Klimas. Raimund von Klebelsberg followed as editor in 1928, he started Zeitschrift für Gletscherkunde und Glazialgeologie anew with Vol.1 in 1950, followed by Hans Kinzl and Herfried Hoinkes in 1970 and by Gernot Patzelt and Michael Kuhn from 1979 to 2001. Herausgeber Michael Kuhn Editor Schriftleitung Angelika Neuner & Mercedes Blaas Executive editors Wissenschaftlicher Beirat Editorial advisory board Jon Ove Hagen, Oslo Ole Humlum, Longyearbyen Peter Jansson, Stockholm Georg Kaser, Innsbruck Vladimir Kotlyakov, Moskva Heinz Miller, Bremerhaven Koni Steffen, Boulder ISSN 0044-2836 Figure on front page: “Vue prise de la Voute nommée le Chapeau, du Glacier des Bois, et des Aiguilles. du Charmoz.”; signed down in the middle “fait par Jn. Ante. Linck.”; coloured contour etching; 36.2 x 48.7 cm; Bibliothèque publique et universitaire de Genève, 37 M Nr. 1964/181; Photograph by H. J. -

One Hundred Years Ago (With Extracts from the Alpine Journal)

CA RUSSELL One Hundred Years Ago (with extracts from the Alpine Journal) (Plates 57-61) he fIrst attempt to ascend Mont Blanc in the twentieth centuryl was T made on Thursday, but without success. Even before the Pierre Pointue was reached the snow was found to be so deep that racquettes had to be used, while at the Grand Junction of the Glacier de Taconna progress was rendered very difficult from the same cause. On reaching Grands Mulets (10,007 feet), it was decided to give up the task of reaching the actual summit owing to the great depth of the snow and the intense cold, and signs ofwind. Moreover, one of the guides was suffering from frostbite. The party, consisting of Mr. Crofts and the guides Joseph Demarchi, Fran~ois Mugnier and Jules Monard spent the night at the Grands Mulets, and descended to Chamonix next morning. The severe conditions experienced by Mr Crofts' party on 17 January 1901 were prolonged by exceptionally cold winds which persisted for several weeks in many Alpine regions. Although little mountaineering was possi ble the fust ski ascents of two peaks were completed: on 30 March Henry Hoek and Ernst Schottelius climbed the Dammastock; and on 28 May Schottelius, accompanied by Friedrich Reichert, reached the summit of the Oberaarhorn. A period of fine weather which commenced in May prompted an early start to the climbing season and by the end of the fIrst week in June a number of successful expeditions had been completed. Throughout Switzerland glorious, warm weather is being experienced, and with it Alpine climbing has begun in real earnest. -

Alpine Thermal and Structural Evolution of the Highest External Crystalline Massif: the Mont Blanc

TECTONICS, VOL. 24, TC4002, doi:10.1029/2004TC001676, 2005 Alpine thermal and structural evolution of the highest external crystalline massif: The Mont Blanc P. H. Leloup,1 N. Arnaud,2 E. R. Sobel,3 and R. Lacassin4 Received 5 May 2004; revised 14 October 2004; accepted 15 March 2005; published 1 July 2005. [1] The alpine structural evolution of the Mont Blanc, nappes and formed a backstop, inducing the formation highest point of the Alps (4810 m), and of the of the Jura arc. In that part of the external Alps, NW- surrounding area has been reexamined. The Mont SE shortening with minor dextral NE-SW motions Blanc and the Aiguilles Rouges external crystalline appears to have been continuous from 22 Ma until at massifs are windows of Variscan basement within the least 4 Ma but may be still active today. A sequential Penninic and Helvetic nappes. New structural, history of the alpine structural evolution of the units 40Ar/39Ar, and fission track data combined with a now outcropping NW of the Pennine thrust is compilation of earlier P-T estimates and geo- proposed. Citation: Leloup, P. H., N. Arnaud, E. R. Sobel, chronological data give constraints on the amount and R. Lacassin (2005), Alpine thermal and structural evolution of and timing of the Mont Blanc and Aiguilles Rouges the highest external crystalline massif: The Mont Blanc, massifs exhumation. Alpine exhumation of the Tectonics, 24, TC4002, doi:10.1029/2004TC001676. Aiguilles Rouges was limited to the thickness of the overlying nappes (10 km), while rocks now outcropping in the Mont Blanc have been exhumed 1.