Antitrust Law Amidst Financial Crises

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preston Bus Station

th July 2020 from 19 43 Preston Bus Station 43 Preston Railway Station Royal Cottom, Ancient Oak ane 44 yles L Preston Ho Hospital Cottom, Hoyles Lane e 44 Lan 43 Merrytrees Fulwood Wychnor Royal Preston Hospital mWay 44 Cotta Bampton Drive Terminus 44 Creswell Avenue L ea R oa W d oodp Plungingt l umpt o Tulk eth on R n R 44 Mill d Lane d d Preston Bus Station Ends pool R 43 Black Ingol, Cresswell Avenue Blackpool Road Cottom, Bampton Drive .co.ukLarches www.prestonbus Avenue 44 Ingol, Cresswell Avenue PrestonBusLtd Social icon Circle Only use blue and/or white. For more details check out our Preston Bus Station Brand Guidelines. @PrestonBus Preston 43 Bus Contact us: Station Preston Bus Ltd 221 Deepdale Road Preston PR1 6NY [email protected] Rotala Preston - Royal Preston Hospital 43 via Cottam Monday to Friday Ref.No.: 21P Commencing Date: 20/07/2020 Service No 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 Preston Bus Stn 0545 0615 0645 0715 0745 0815 0845 0915 0945 1015 1045 1115 Preston Railway Station 0550 0620 0650 0720 0750 0820 0850 0920 0950 1020 1050 1120 Cottam Ancient Oak 0600 0630 0700 0730 0800 0830 0900 0930 1000 1030 1100 1130 Cottam Hoyles Ln 0608 0638 0708 0738 0808 0838 0908 0938 1008 1038 1108 1138 Fulwood Wychnor 0613 0643 0713 0743 0813 0843 0913 0943 1013 1043 1113 1143 Royal Preston Hospital 0623 0653 0723 0753 0823 0853 0923 0953 1023 1053 1123 1153 RotalaRotala Service No 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 43 Preston Bus Stn 1145 1215 1245 1315 1345 1415 1445 1515 1545 1615 1645 1720 Preston Railway Station 1150 -

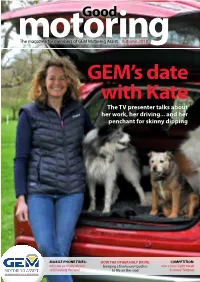

GEM's Date with Kate

Good motoringThe magazine for members of GEM Motoring Assist Autumn 2018 GEM’s date with Kate The TV presenter talks about her work, her driving... and her penchant for skinny dipping MOBILE PHONE FINES: HOW THE OTHER HALF DRIVE: COMPETITION: why are so many drivers bringing a few luxury touches win a two-night break still flouting the law? to life on the road in sunny Torquay 2008 2010 2011 2013 2014 2015 2017 2018 GOLD WINNER WINNERS AGAIN! THANKS FOR SUPPORTING US CONTENTS AUTUMN 2018 FEATURES 12 Your opportunity to win a wonderful two-night break for two people at classy On the cover Orestone Manor in south Devon. 14 Sharing the roads: Peter Rodger offers his thoughts on the value of stepping into another road user’s shoes, and Good Motoring editor James Luckhurst picks up some wise advice for staying safe on horseback. THESE ROADS WERE MADE FOR SHARING 20 GEM member survey: in this edition we What can drivers and riders do to ensure a safer road consider your opinions on car-buying and environment? Understanding each others’ needs - future mobility. 16 and respecting a horse’s brain - are key! 24 Speed enforcement: Neil Barrett lines up an array of cameras, cops and vans to understand why it’s done, and how effective devices are in reducing collisions. 28 At the wheel with Kate Humble: the TV On the cover presenter shares her thoughts on driving, skinny-dipping and why she wanted to be a professional gypsy. ADVENTURES 32 Western France and Atlantic Spain in the company of Rod Ashley. -

Appendix 5 Fylde

FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 LANCASTER - GARSTANG - POULTON - BLACKPOOL 42 via Galgate - Great Eccleston MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ LANCASTER Bus Station 1900 2015 2130 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 1909 2024 2139 LANCASTER University Gates 1912 2027 2142 GALGATE Crossroads 1915 2030 2145 CABUS Hamilton Arms 1921 2036 2151 GARSTANG Bridge Street 1926 2041 2156 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 1935 2050 2205 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 1939 2054 2209 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 1943 2058 2213 POULTON St Chads Church 1953 2108 2223 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 1958 2113 2228 BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2010 2125 2240 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council BLACKPOOL - POULTON - GARSTANG - LANCASTER 42 via Great Eccleston - Galgate MONDAY TO SATURDAY Service Number 42 42 42 $ $ $ BLACKPOOL Abingdon Street 2015 2130 2245 BLACKPOOL Layton Square 2020 2135 2250 POULTON Teanlowe Centre 2032 2147 2302 GREAT ECCLESTON Square 2042 2157 2312 ST MICHAELS Grapes Hotel 2047 2202 2317 CHURCHTOWN Horns Inn 2051 2206 2321 GARSTANG Park Hill Road 2059 2214 2329 CABUS Hamilton Arms 2106 2221 2336 GALGATE Crossroads 2112 2227 2342 LANCASTER University Gates 2115 2230 2345 SCOTFORTH Boot and Shoe 2118 2233 2348 LANCASTER Bus Station 2127 2242 2357 $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council LIST OF ALTERNATIVE TRANSPORT SERVICES AVAILABLE – Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 2 between Lancaster and University Stagecoach in Lancaster Service 40 between Lancaster and Garstang (limited) Blackpool Transport Service 2 between Poulton and Blackpool FYLDE DISTRICT - APPENDIX 5 SUBSIDISED LOCAL BUS SERVICE EVENING AND SUNDAY JOURNEYS PROPOSED TO BE WITHDRAWN FROM 18 MAY 2014 PRESTON - LYTHAM - ST. -

Bus Travel to Myerscough College 2017/2018 Academic Year

Timetable Septemberservice 2017 80update: amended Bus Travel to Myerscough College 2017/2018 academic year Daily direct services from: • Clitheroe • Whalley • Longridge • Goosnargh • Burnley • Accrington • Blackburn • Samlesbury • Broughton • Fleetwood • Cleveleys • Blackpool • Poulton • St Annes • Lytham • Warton • Freckleton • Kirkham • Preston • Fulwood • Broughton • Ingol • Inskip • Elswick • Great Eccleston Connections from: • Lancaster & Morecambe • Fylde Coast • South Ribble & South Preston • Bolton • Horwich • Chorley • Bamber Bridge SERVICES AVAILABLE TO ALL • Including NoWcard Holders • board and alight at any recognised bus stops along routes Contact Details Finance Office Myerscough College Bilsborrow Preston PR3 ORY 01995 642218 [email protected] www.myerscough.ac.uk Preston Bus 221 Deepdale Road Preston PR1 6NY 01772 253671 [email protected] www.prestonbus.co.uk Facebook “f” Logo CMYK@PrestonBus / .eps Facebook “f” Logo CMYK / .eps PrestonBusLtd Transdev (Lancashire United) FREEPOST LUL (no stamp required) 0845 2 72 72 72 [email protected] www.lancashirebus.co.uk Services Clitheroe, Whalley, Longridge, Goosnargh to Myerscough Preston Bus service 995 Burnley, Accrington, Blackburn, Samlesbury, Broughton to Myerscough Transdev 852 Lancaster & Morecambe – Stagecoach service 40/41 alight at Barton Grange Garden Centre or Roebuck, catch Free Shuttle Bus service* 401 to Myerscough. Bolton, Horwich, Chorley, Clayton-le-Woods, Bamber Bridge, Longridge – scheme passes valid for use on any South Ribble -

Save Preston Bus Station Banner

6DYH3UHVWRQ%XV6WDWLRQ EDQQHU 7KLVEDQQHUZDVGHVLJQHGDQG PDGHE\EDQQHUPDNHU(G+DOO +HFRQWDFWHGWKH6DYH3UHVWRQ%XV 6WDWLRQJURXSDQGRIIHUHGWRPDNHD EDQQHUWRKHOSWKHFDXVHWRVDYHWKH EXLOGLQJIURPGHPROLWLRQ ,WZDVFDUULHGLQDSDUDGHRQ 6DWXUGD\1RYHPEHUZKLFK EHFDPHDFHOHEUDWLRQRIWKHEXLOGLQJ EHLQJJUDQWHG*UDGH,,OLVWHGVWDWXV )RUPDQ\RIWKHVXSSRUWHUVLWZDV WKHÀUVWWLPHWKH\KDGPHWDVPXFK RIWKHFDPSDLJQKDGEHHQFDUULHG RXWRQVRFLDOPHGLD 2QORDQIURP,Q&HUWDLQ3ODFHV %XV6WDWLRQ&RQQHFWLRQV 7KHVHFDVHVFRQWDLQLWHPVEURXJKW LQE\SHRSOHZKRUHVSRQGHGWRD FDOORXWIRUREMHFWVWKDWFRQQHFWWKHP WR3UHVWRQ%XV6WDWLRQ 7KH\RIIHUDJOLPSVHLQWRZKDWWKH EXLOGLQJKDVPHDQWWRWKHSHRSOHRI 3UHVWRQDQGIXUWKHUDÀHOGRYHUWKH ODVW\HDUV 6DUDK:DONHU 7KLVSKRWRJUDSKZDVWDNHQE\ 6DUDKҋVGDXJKWHU(PPDLQ 6KHLVQRZVWXG\LQJDUFKLWHFWXUDO GHVLJQDW/LYHUSRRO8QLYHUVLW\ 1RUPDQ3D\QH 1RUPDQ3D\QHXVHGWKLV1DWLRQDO ([SUHVVGLVFRXQWFDUGLQWKHV ZKHQKHZDVDVWXGHQWDW8&/DQ DQGWUDYHOOHGIURP3UHVWRQ%XV 6WDWLRQWR6RXWKDPSWRQ +HOHQ/LQGVD\ 7KLVFROOHFWLRQRILWHPVUHÁHFWV +HOHQҋVORQJLQWHUHVWLQ3UHVWRQ%XV 6WDWLRQ7KHFRQFUHWHIUDJPHQWDQG &KULVWPDVFDUGZHUHIURP FROOHDJXHVDW/DQFDVKLUH3RVW6KH DOVRKDVDSDUWLQWKHÀOP &KDUOHV4XLFN 7KHSRVWFDUGZDVDSUHVHQW,WLV DOZD\VNHSWLQWKHEDFNRIKLV QRWHERRNDQGLVFDUULHGDWDOOWLPHV DVUHIHUHQFH 0U/HDYHU :DVDNHHQEXVVSRWWHU7KLV EXVVSRWWLQJPDQXDOGDWHVIURPWKH VDQGPDQ\RIWKHEXVHVLQLW XVHG3UHVWRQ%XV6WDWLRQ 5LWD:KLWORFN 7KLVPXJDQGFRDVWHUXVHGWREH VROGLQ3UHVWRQ7RXULVW,QIRUPDWLRQ &HQWUHZKHUH5LWDZDV0DQDJHU 6KHSXUFKDVHGWKHPDVVKHORYHV %UXWDOLVWDUFKLWHFWXUH &KULV/RQHUJDQ &KULVLVD6HQLRU(QJLQHHUDW$583 LQ0DQFKHVWHU$OORIWKHVWDIILQWKH RIÀFHKDYHDFXEHZLWKWKHLUSLFWXUH RQ,WDOVRLQFOXGHVVRPHWKLQJ -

PRESTON - FULWOOD - WOODPLUMPTON - BROUGHTON 15 Via Wychnor - Royal Preston Hospital - ASDA - Longsands MONDAY to FRIDAY

TENDERED BUS SERVICE REVISIONS Page 1 of 6 COMMENCING 4 NOVEMBER 2019 PRESTON - FULWOOD - WOODPLUMPTON - BROUGHTON 15 via Wychnor - Royal Preston Hospital - ASDA - Longsands MONDAY TO FRIDAY Service Number 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ PRESTON Bus Station 0615 0715 0815 0920 1025 1125 1225 1325 1425 1525 1635 1740 1840 PRESTON Deepdale Road Depot 0621 0721 0822 0926 1031 1131 1231 1331 1431 1531 1643 1748 1846 LONGSANDS Longsands Lane 0630 0730 0831 0935 1040 1140 1240 1340 1440 1540 1654 1759 1855 FULWOOD ASDA Store 0635 0735 0836 0940 1045 1145 1245 1345 1445 1545 1659 1804 1900 FULWOOD Royal Preston Hospital 0643 0743 0845 0948 1053 1153 1253 1353 1453 1554 1708 1813 1908 FULWOOD Wychnor 0651 0751 0854 0956 1101 1201 1301 1401 1501 1603 1717 1821 1916 WOODPLUMPTON Whittle Green 0657 0757 0901 1002 1107 1207 1307 1407 1507 1609 1723 1827 1922 BROUGHTON Sunningdale ----- ----- 0905 1005 1110 1210 1310 1410 1510 1614 ----- ----- ----- $ - Operated on behalf of Lancashire County Council BROUGHTON - WOODPLUMPTON - FULWOOD - PRESTON 15 via Longsands - ASDA - Royal Preston Hospital - Wychnor MONDAY TO FRIDAY Service Number 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 15 $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ $ BROUGHTON Sunningdale ----- ----- ----- 0906 1006 1111 1211 1311 1411 1511 1615 ----- ----- WOODPLUMPTON Whittle Green ----- 0659 0759 0909 1009 1114 1214 1314 1414 1514 1618 1724 1828 FULWOOD Wychnor ----- 0707 0808 0917 1017 1122 1222 1322 1422 1522 1627 1732 1835 FULWOOD Royal Preston Hospital ----- 0715 0818 0925 1025 -

Passenger Information During Snow Disruption December 2010

Passenger information during snow disruption December 2010 A Rail passenger Information during snow disruption December 2010 Headline Findings 1. The National Rail Enquiries (NRE) website appears to have coped well with very high volumes 2. The online real time journey planner on the NRE website did not show correct information for some train operating companies (TOCs) 3. The online journey planners on TOC and third-party websites did not generally reflect the contingency timetables in operation 4. Tickets continued to be available for sale online for many trains that would not run 5. Station displays appear to have reflected formal contingency timetables, except for Southeastern 6. Station displays and online Live Departure Boards did not always keep pace with events 7. The NRE call centres appear to have provided good information, but queuing times of 11 or 12 minutes were common. 1 The National Rail Enquiries appears to have coped well with very high volumes We saw no evidence that the NRE website crashed or was slower than usual, despite a large spike in volume (Chris Scoggins reported that the volume on 2 December was twice the previous record peak on 7 January 2010). 2 The online real time journey planner on the NRE website did not show correct information for some train operating companies NRE had to advise passengers not to use the journey planner for enquiries about East Coast, Southeastern and South West Trains. This was a significant failure, with three scenarios: 2a Although the journey planner showed services from a contingency timetable for East Coast on 1 and 2 December, it also showed services from the base timetable that were no longer running. -

M0285 OCR (CS 150Dpi).Pdf

@[3(£cMarconi AVI()NICS House Journal of GEe-Marconi Avionics Limited Issue 2 PRINCE OF WALES MASSIVE DONATION HANDED OVER TO AWARD FOR GMAv MEDWAY SCANNER APPEAL A revolutionary new collections, sponsored swims, thermal imaging sensor, "The Gift is Right" - sales of books and other arti with wide application to John Colston cle s, and big social and sport "Some said it was ing events. All these - and emergency and security 'impossible' . Others said many more - have , together, services, has won the 1993 'extremely ambitious' ", said invol ve d thousands ·of ge ner "Prince of Wales Award Dr Mohan Ve lamati, Chairman ous people. for Innovation". of the Me dway Scanner Four Times Over Target! Appeal, re ferring to the Fund's The Aw ard was presente d £1 million target when he Over 70 pe ople re presenting jointly to GEC-Marconi came to Airport Works in all those who had de dicated Avionics, Sensors Division, April to re ceive a cheque for time and effort to our fund with GEC-Marconi Materials £101,445. raising were at the ce remony Technology and the Defence hosted by Divisional Manag Re se arch Agency. The ce re This spectacular contribu ing Director John Colston for mony took place at the UK Fire tion to the Fund has been the cheque handover. He said Service College at Moreton-in raised during the last two years "W hen a Committee was Marsh, Gl ouce stershire , and by the efforts of Rocheste r empl oyee s and their families forme d to co-ordinate the was broadcast during the Company's Appe al, we BBCl "Tomorrow's Worl d" taking part in, and contributing to, a host of events both thought a target of £25,000 programme on Wedne sday, serious and funny. -

2021 Book News Welcome to Our 2021 Book News

2021 Book News Welcome to our 2021 Book News. As we come towards the end of a very strange year we hope that you’ve managed to get this far relatively unscathed. It’s been a very challenging time for us all and we’re just relieved that, so far, we’re mostly all in one piece. While we were closed over lockdown, Mark took on the challenge of digitalising some of Venture’s back catalogue producing over 20 downloadable books of some of our most popular titles. Thanks to the kind donations of our customers we managed to raise over £3000 for The Christie which was then matched pound for pound by a very good friend taking the total to almost £7000. There is still time to donate and download these books, just click on the downloads page on our website for the full list. We’re still operating with reduced numbers in the building at any one time. We’ve re-organised our schedules for packers and office staff to enable us to get orders out as fast as we can, but we’re also relying on carriers and suppliers. Many of the publishers whose titles we stock are small societies or one-man operations so please be aware of the longer lead times when placing orders for Christmas presents. The last posting dates for Christmas are listed on page 63 along with all the updates in light of the current Covid situation and also the impending Brexit deadline. In particular, please note the change to our order and payment processing which was introduced on 1st July 2020. -

BAE Undertakings of the Merger Between British Aerospace Plc And

ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS BUSINESS OF THE GENERAL ELECTRIC COMPANYPLC UNDERTAKINGS GIVEN TO THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR TRADE AND INDUSTRY BY BRITISH AEROSPACE PLC PURSUANT TO S75G(l) OF THE FAIR TRADING ACT 1973 WHEREAS: (a) On 27 April 1999 British Aerospace pic ("BAE SYSTEMS") agreed with The General Electric Company pic ("GEC") the proposed merger ("the merger") of GEC's defence electronics business Marconi Electronic Systems ("MES") with BAE SYSTEMS; (b) The merger came within the jurisdiction of Council Regulation (EEC) No. 4064/89 on the control of concentrations between undertakings ("the EC Merger Regulation"); (c) Article 296 (ex Article 223) of the EC Treaty permits any Member State to take such measures as it considers necessary to protect its essential security interests which are connected with the production of or trade in arms, munitions and war material; (d) BAE SYSTEMS was requested, under the former Article 223(I)(b) of the EC Treaty, not to notify the military aspects of the merger to the European Commission under the EC Merger Regulation; (e) The military aspects of the merger were consequently considered by Her Majesty's Government under national merger control law; (f) The Secretary of State has power under section 75(1) of the Fair Trading Act 1973 to make a merger reference to the Competition Commission and, under section 7SG(l), to accept undertakings as an alternative to making such a reference; (g) The Secretary of State has requested that the Director General of Fair Trading seek undertakings from BAE SYSTEMS in order to remedy or prevent the adverse effects ofthe merger. -

Integracija Evropske Obrambne Industrije

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Andrej Stres INTEGRACIJA EVROPSKE OBRAMBNE INDUSTRIJE Diplomsko delo Ljubljana 2007 UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA DRUŽBENE VEDE Andrej Stres Mentor: doc. dr. Iztok Prezelj Somentor: asist. mag. Erik Kopač INTEGRACIJA EVROPSKE OBRAMBNE INDUSTRIJE Diplomsko delo Ljubljana 2007 INTEGRACIJA EVROPSKE OBRAMBNE INDUSTRIJE Diplomsko delo obravnava spremembe v evropski obrambni industriji vse od konca 2. svetovne vojne. Na začetku predstavi proces povezovanja obrambne industrije v času hladne vojne v treh časovnih obdobjih. Sledi predstavitev trendov povezovanja obrambne industrije po koncu hladne vojne, podkrepljenih z vzroki, ki spodbujajo in zavirajo proces povezovanja obrambne industrije v Evropi. Omenjeni proces, voden s strani obrambnih podjetij, je prikazan s pomočjo koncentracije, privatizacije in internacionalizacije obrambne industrije. Obravnava tudi liberalističen in merkantilističen pristop k integraciji obrambne industrije na primeru Velike Britanije in Francije. Proces institucionalne integracije obrambne industrije, ki predstavlja poskus meddržavnega povezovanja obrambne industrije, prikaže v študiji primerov najpomembnejših institucij na tem področju. V zadnjem poglavju s predstavitvijo slovenske obrambne industrije v obdobju po osamosvojitvi leta 1991 umesti obrambno industrijo v Sloveniji v evropsko dogajanje na tem področju ter nakaže možnosti za njen nadaljnji razvoj. Ključne besede: obrambna industrija, ekonomska integracija, Evropa, Slovenija. INTEGRATION OF EUROPEAN DEFENCE INDUSTRY This diploma work deals with changes in defence industry in Europe since the end of Second World War. At the begininng it divides the process of binding up the European defence industry in Cold War on three periods. It continues with the introduction of modern trends in binding up the defence industry after the end of Cold War with help by causes that stimulate and interfere the process of European defence integration. -

Trends in Space Commerce

Foreword from the Secretary of Commerce As the United States seeks opportunities to expand our economy, commercial use of space resources continues to increase in importance. The use of space as a platform for increasing the benefits of our technological evolution continues to increase in a way that profoundly affects us all. Whether we use these resources to synchronize communications networks, to improve agriculture through precision farming assisted by imagery and positioning data from satellites, or to receive entertainment from direct-to-home satellite transmissions, commercial space is an increasingly large and important part of our economy and our information infrastructure. Once dominated by government investment, commercial interests play an increasing role in the space industry. As the voice of industry within the U.S. Government, the Department of Commerce plays a critical role in commercial space. Through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Department of Commerce licenses the operation of commercial remote sensing satellites. Through the International Trade Administration, the Department of Commerce seeks to improve U.S. industrial exports in the global space market. Through the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, the Department of Commerce assists in the coordination of the radio spectrum used by satellites. And, through the Technology Administration's Office of Space Commercialization, the Department of Commerce plays a central role in the management of the Global Positioning System and advocates the views of industry within U.S. Government policy making processes. I am pleased to commend for your review the Office of Space Commercialization's most recent publication, Trends in Space Commerce. The report presents a snapshot of U.S.