Milestone: E Ast L Os of T He V Oices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Pomegranate Cycle

The Pomegranate Cycle: Reconfiguring opera through performance, technology & composition By Eve Elizabeth Klein Bachelor of Arts Honours (Music), Macquarie University, Sydney A PhD Submission for the Department of Music and Sound Faculty of Creative Industries Queensland University of Technology Brisbane, Australia 2011 ______________ Keywords Music. Opera. Women. Feminism. Composition. Technology. Sound Recording. Music Technology. Voice. Opera Singing. Vocal Pedagogy. The Pomegranate Cycle. Postmodernism. Classical Music. Musical Works. Virtual Orchestras. Persephone. Demeter. The Rape of Persephone. Nineteenth Century Music. Musical Canons. Repertory Opera. Opera & Violence. Opera & Rape. Opera & Death. Operatic Narratives. Postclassical Music. Electronica Opera. Popular Music & Opera. Experimental Opera. Feminist Musicology. Women & Composition. Contemporary Opera. Multimedia Opera. DIY. DIY & Music. DIY & Opera. Author’s Note Part of Chapter 7 has been previously published in: Klein, E., 2010. "Self-made CD: Texture and Narrative in Small-Run DIY CD Production". In Ø. Vågnes & A. Grønstad, eds. Coverscaping: Discovering Album Aesthetics. Museum Tusculanum Press. 2 Abstract The Pomegranate Cycle is a practice-led enquiry consisting of a creative work and an exegesis. This project investigates the potential of self-directed, technologically mediated composition as a means of reconfiguring gender stereotypes within the operatic tradition. This practice confronts two primary stereotypes: the positioning of female performing bodies within narratives of violence and the absence of women from authorial roles that construct and regulate the operatic tradition. The Pomegranate Cycle redresses these stereotypes by presenting a new narrative trajectory of healing for its central character, and by placing the singer inside the role of composer and producer. During the twentieth and early twenty-first century, operatic and classical music institutions have resisted incorporating works of living composers into their repertory. -

Personality Learning Theories

Psychodynamic Theories Cognive Social Trait Theory Personality Learning Theories *An individual’s unique paern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that persists over me and across situaons. Humanisc Theories Issues in Personality 1. Free will or determinism? 2. Nature or nurture? 3. Past, present, or future? 4. Uniqueness or universality? 5. Equilibrium or growth? 6. Opmism or pessimism? Psychodynamic Theories Sigmund Freud Behavior is the product of psychological forces within the individual, oen Neo‐Freudians outside of conscious awareness Central Tenets 1) Much of mental life is unconscious. People may behave in ways they themselves don’t understand. 2) Mental processes act in parallel, leading to conflicng thoughts and feelings. 3) Personality paerns begin in childhood. Childhood experiences strongly affect personality development. 4) Mental representaons of self, others, and relaonships guide interacons with others. 5) The development of personality involves learning to regulate aggressive and sexual feelings as well as becoming socially independent rather than dependent. Sigmund Freud Sigmund Freud • The human PERSONALITY is an energy system. • It is the job of psychology to invesgate the change, transmission and conversion of this ‘psychic energy’ within the personality which shape and determine it. These Drives are the ‘Energy’ Structure of the Mind – Id – Super‐ego – Ego Id • Exists enrely in the unconscious (so we are never aware of it). • Our hidden true animalisc wants and desires. • Works on the Pleasure Principle • Avoid pain and receive instant graficaon. Ego If you want to be with someone. Your id says just take them, but your ego does not want to end up in jail. -

1 Time and the Unconscious Mind

Time and the Unconscious Mind: A Brief Commentary Julia Mossbridge, M.A., Ph.D. Visiting Scholar, Department of Psychology, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208 Founder and Research Director, Mossbridge Institute, LLC, Evanston, IL 60202 Please send correspondence to Julia Mossbridge: [email protected] Most of us think we know some basic facts about how time works. The facts we believe we know are based on a few intuitions about time, which are, in turn, based on our conscious waking experiences. As far as I can tell, these intuitions about time are something like this: 1) There is a physical world in which events occur, 2) These events are mirrored by our perceptual re-creation of them in essentially the same order in which they occur in the physical world, 3) This re-creation of events occurs in a linear order based on our conscious memory of them (e.g., event A is said to occur before event B if at some point we do remember event A but we don’t yet remember event B, and at another point we remember both events), 4) Assuming we have good memories, what we remember has occurred in the past and what we don’t remember but we can imagine might: a) never occur, b) occur when we are not conscious, or c) occur in the future. These intuitions are excellent ones for understanding our conscious conception of ordered events. However, they do not tell us anything about how the non-conscious processes in our brains navigate events in time. Currently, neuroscientists assume that neural processes of which we are unaware, that is, non-conscious processes, create conscious awareness as a reflection of physical reality (Singer, 2015). -

Unit 10 — Personality

UNIT 10 — PERSONALITY Vocabulary Term Definition of Term Example Personality An individual’s characteristic pattern of thinking, feeling, Aggressive, funny, acting. Free Association In psychoanalysis, a method of exploring the unconscious in which the person relaxes and says whatever comes to mind, no matter how trivial or embarrassing. Psychoanalysis Freud’s theory of personality that attributes thoughts and Therapy through talking. actions to unconscious motives and conflicts; the techniques used in treating psychological disorders by seeking to expose and interpret unconscious tensions. Unconscious According to Freud, a reservoir of mostly unacceptable Id, Repression- forcible thoughts, wishes, feelings, and memories. According to blocking of unacceptable contemporary psychologists, information processing of which passions and thoughts. we are unaware. Id Contains a reservoir of unconscious psychic energy that, Needs, drives, instincts, and according to Freud, strives to satisfy basic sexual and repressed material. What we aggressive drives; operates on the pleasure principle, want to do. demanding immediate gratification. Ego The largely conscious, “executive” part of personality that, What we can do; reality according to Freud, mediates among the demands of the id, superego, and reality; operates under the reality principle, satisfying the id’s desires in ways that will realistically bring pleasure rather than pain. Superego The part of personality that, according to Freud, represents Operates based on the Moral internalized ideals and provides standards for judgment (the Principle. What we should do. conscience) and for future aspirations. Psychosexual Stages The childhood stages of development during which, according Oral, Anal, Phallic, Latency, to Freud, the id’s pleasure seeking energies focus on distinct Genital erogenous zones. -

She-Condom Makes Its Debut at U. Center, Page 1 0

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Student Newspaper (Amicus, Advocate...) Archives and Law School History 1994 Amicus Curiae (Vol. 4, Issue 9) Repository Citation "Amicus Curiae (Vol. 4, Issue 9)" (1994). Student Newspaper (Amicus, Advocate...). 409. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/newspapers/409 Copyright c 1994 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/newspapers She-Condom makes its debut at U. Center, page 1 0 MARSHALL-WYTHE SCHOOL OF LAW America s First Law School VOLUME IV, ISSUE NINE MONDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 1994 TWENTY PAGES Short reinstated; will graduate In• summer By LEEANNE MORRIS report that he will reenroll at M Acting Dean Paul Marcus has Wand fmish his final nine credits decided to allow former SBA this summer in Texas. The President Kyle Short to readmit credits will be transferred and to Marshall-Wythe at the end of applied to his degree. this semester. "Hopefully I'll be able to find Marcus prevented Short frop1 the classes I need this summer. I enrolling this semester as hope to be finished and graduated punishment for an Honor Code by Aug. 8," Short said. violation last fall. In doing so, Marcus was unavailable for Marcus overturned the sanction comment on the matter. His recommended by the Judicial opinion issued last semester said Council that Short be publicly that he would grant Short's reprimanded. petition if he was convinced that ''I'm thrilled to be Short acknowledged, "privately readmitted," Short said. -

A Dangerous Method

A David Cronenberg Film A DANGEROUS METHOD Starring Keira Knightley Viggo Mortensen Michael Fassbender Sarah Gadon and Vincent Cassel Directed by David Cronenberg Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Official Selection 2011 Venice Film Festival 2011 Toronto International Film Festival, Gala Presentation 2011 New York Film Festival, Gala Presentation www.adangerousmethodfilm.com 99min | Rated R | Release Date (NY & LA): 11/23/11 East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Donna Daniels PR Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Donna Daniels Ziggy Kozlowski Carmelo Pirrone 77 Park Ave, #12A Jennifer Malone Lindsay Macik New York, NY 10016 Rebecca Fisher 550 Madison Ave 347-254-7054, ext 101 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 New York, NY 10022 Los Angeles, CA 90036 212-833-8833 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8844 fax 323-634-7030 fax A DANGEROUS METHOD Directed by David Cronenberg Produced by Jeremy Thomas Co-Produced by Marco Mehlitz Martin Katz Screenplay by Christopher Hampton Based on the stage play “The Talking Cure” by Christopher Hampton Based on the book “A Most Dangerous Method” by John Kerr Executive Producers Thomas Sterchi Matthias Zimmermann Karl Spoerri Stephan Mallmann Peter Watson Associate Producer Richard Mansell Tiana Alexandra-Silliphant Director of Photography Peter Suschitzky, ASC Edited by Ronald Sanders, CCE, ACE Production Designer James McAteer Costume Designer Denise Cronenberg Music Composed and Adapted by Howard Shore Supervising Sound Editors Wayne Griffin Michael O’Farrell Casting by Deirdre Bowen 2 CAST Sabina Spielrein Keira Knightley Sigmund Freud Viggo Mortensen Carl Jung Michael Fassbender Otto Gross Vincent Cassel Emma Jung Sarah Gadon Professor Eugen Bleuler André M. -

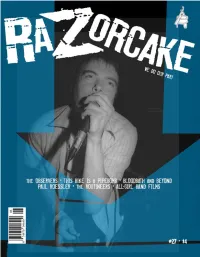

Read Razorcake Issue #27 As A

t’s never been easy. On average, I put sixty to seventy hours a Yesterday, some of us had helped our friend Chris move, and before we week into Razorcake. Basically, our crew does something that’s moved his stereo, we played the Rhythm Chicken’s new 7”. In the paus- IInot supposed to happen. Our budget is tiny. We operate out of a es between furious Chicken overtures, a guy yelled, “Hooray!” We had small apartment with half of the front room and a bedroom converted adopted our battle call. into a full-time office. We all work our asses off. In the past ten years, That evening, a couple bottles of whiskey later, after great sets by I’ve learned how to fix computers, how to set up networks, how to trou- Giant Haystacks and the Abi Yoyos, after one of our crew projectile bleshoot software. Not because I want to, but because we don’t have the vomited with deft precision and another crewmember suffered a poten- money to hire anybody to do it for us. The stinky underbelly of DIY is tially broken collarbone, This Is My Fist! took to the six-inch stage at finding out that you’ve got to master mundane and difficult things when The Poison Apple in L.A. We yelled and danced so much that stiff peo- you least want to. ple with sourpusses on their faces slunk to the back. We incited under- Co-founder Sean Carswell and I went on a weeklong tour with our aged hipster dancing. -

Making Company of Darkness Joshua Evan Borgmann Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1999 Making company of darkness Joshua Evan Borgmann Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Creative Writing Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Borgmann, Joshua Evan, "Making company of darkness " (1999). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 7097. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/7097 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Making company of darkness by Joshua Evan Borgmann . A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partialfulfillment of the requirements for the degreeof MASTER OFARTS Major: English (Creative Writing) Major Professor: Neal Bowers Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 1999 11 Graduate College Iowa State University This is to certify that the Master's thesis of Joshua Evan Borgmann has met the requirements ofIowa State University Major Professor For the Major Program For the Graduate College m TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INSALUBRIOUS BIFURCATIONS 1 Family Portrait at 23 2 Family 3 Family Spirit 4 Insalubrious Bifurcation ofthe Post-Nuclear Family Schema 5 Christmas Eves 6 Holiday Edge 7 Food, Football, Family 9 Wal-Mart Christian 11 Devil's Advocate 13 Religion in Ice 14 Deicide 15 Suicide Poem # 23 16 Suicide Poem # 24 17 23 to 2 18 Sadistic Auto-Masochistic Persecution 19 Random SelfIndulgent Shit 20 High School High Via the Lost Highway 23 Forgetting '87 24 Thirteen 25 Absence ofLight 26 Windows 27 The House 28 Old Woman 29 In the Night 30 Goathoms 31 H. -

2005 – 2007 PALO ALTO COLLEGE BULLETIN Catalog of Courses

Changes to printed publication are marked in magenta ink. Changes to printed publication are marked in magenta ink. 2005 – 2007 PALO ALTO COLLEGE BULLETIN Catalog of Courses Palo Alto College is accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (1866 Southern Lane, Decatur, Georgia 30033-4097: Telephone number (404) 679-4501) to award associate degrees and by the Committee on Animal Technician Activities and Training of the American Veterinary Medical Association. Its programs are approved by the Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board, the Federal Aviation Administration, and the American Society of Transportation and Logistics. Palo Alto College is a member of the American Association of Community Colleges, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, the Hispanic Association of Colleges and Universities, the Texas Community Colleges Teachers Association, and the National Council of Marketing and Public Relations. This catalog contains policies, regulations, procedures, and course content effective at the beginning of the Fall Semester 2005. Palo Alto College reserves the right to make changes at any time to reflect current Board policies, administrative regulations and procedures, and applicable State and Federal regulations. The provisions of this bulletin are subject to change without notice and do not constitute a contract between any student and the college. The online version of this cat- alog on the College’s web site contains updated information and changes. Palo Alto College is an Equal Opportunity/Affirmative Action Employer. The Alamo Community College District, including its affiliated colleges, does not discriminate on the basis of race, religion, color, national origin, sex, age, or disability with respect to access, employment pro- grams, or services. -

In BLACK CLOCK, Alaska Quarterly Review, the Rattling Wall and Trop, and She Is Co-Organizer of the Griffith Park Storytelling Series

BLACK CLOCK no. 20 SPRING/SUMMER 2015 2 EDITOR Steve Erickson SENIOR EDITOR Bruce Bauman MANAGING EDITOR Orli Low ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR Joe Milazzo PRODUCTION EDITOR Anne-Marie Kinney POETRY EDITOR Arielle Greenberg SENIOR ASSOCIATE EDITOR Emma Kemp ASSOCIATE EDITORS Lauren Artiles • Anna Cruze • Regine Darius • Mychal Schillaci • T.M. Semrad EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Quinn Gancedo • Jonathan Goodnick • Lauren Schmidt Jasmine Stein • Daniel Warren • Jacqueline Young COMMUNICATIONS EDITOR Chrysanthe Tan SUBMISSIONS COORDINATOR Adriana Widdoes ROVING GENIUSES AND EDITORS-AT-LARGE Anthony Miller • Dwayne Moser • David L. Ulin ART DIRECTOR Ophelia Chong COVER PHOTO Tom Martinelli AD DIRECTOR Patrick Benjamin GUIDING LIGHT AND VISIONARY Gail Swanlund FOUNDING FATHER Jon Wagner Black Clock © 2015 California Institute of the Arts Black Clock: ISBN: 978-0-9836625-8-7 Black Clock is published semi-annually under cover of night by the MFA Creative Writing Program at the California Institute of the Arts, 24700 McBean Parkway, Valencia CA 91355 THANK YOU TO THE ROSENTHAL FAMILY FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT Issues can be purchased at blackclock.org Editorial email: [email protected] Distributed through Ingram, Ingram International, Bertrams, Gardners and Trust Media. Printed by Lightning Source 3 Norman Dubie The Doorbell as Fiction Howard Hampton Field Trips to Mars (Psychedelic Flashbacks, With Scones and Jam) Jon Savage The Third Eye Jerry Burgan with Alan Rifkin Wounds to Bind Kyra Simone Photo Album Ann Powers The Sound of Free Love Claire -

Gardenergardener

TheThe AmericanAmerican GARDENERGARDENER TheThe MagazineMagazine ofof thethe AAmericanmerican HorticulturalHorticultural SocietySociety January/February 2005 new plants for 2005 Native Fruits for the Edible Landscape Wildlife-Friendly Gardening Chanticleer: A Jewel of a Garden The Do’s andand Don’tsDon’ts ofof Planting Under Trees contents Volume 84, Number 1 . January / February 2005 FEATURES DEPARTMENTS 5 NOTES FROM RIVER FARM 6 MEMBERS’ FORUM 8 NEWS FROM AHS AHS’s restored White House gates to be centerpiece of Philadelphia Flower Show entrance exhibit, The Growing Connection featured during United Nations World Food Day events, Utah city’s volunteer efforts during America in Bloom competition earned AHS Community Involvement Award, Great Southern Tree Conference is newest AHS partner. 14 AHS PARTNERS IN PROFILE page 22 The Care of Trees brings passion and professionalism to arboriculture. 44 GARDENING BY DESIGN 16 NEW FOR 2005 BY RITA PELCZAR Forget plants—dream of design. A preview of the exciting and intriguing new plant introductions. 46 GARDENER’S NOTEBOOK Gardening trends in 2005, All-America 22 CHANTICLEER BY CAROLE OTTESEN Selections winners, Lenten rose is perennial of the year, wildlife This Philadephia-area garden is being hailed as one of the finest gardening courses small public gardens in America. online, new Cornell Web site allows rating of 26 NATIVE FRUITS BY LEE REICH vegetable varieties, Add beauty and flavor to your landscape with carefree natives like Florida gardens recover from hurricane damage, page 46 beach plum, persimmon, pawpaw, and clove currant. gardeners can help with national bird count. 31 TURNING A GARDEN INTO A COMMUNITY BY JOANNE WOLFE 50 In this first in a series of articles on habitat gardening, learn how to GROWING THE FUTURE create an environment that benefits both gardener and wildlife. -

Individuation As Spiritual Process: Jung’S Archetypal Psychology and the Development of Teachers

Individuation as Spiritual Process: Jung’s Archetypal Psychology and the Development of Teachers Kathleen Kesson See the published version in the journal: ENCOUNTER: EDUCATION FOR MEANING AND SOCIAL JUSTICE Winter 2003, 16 (4). “…The spirit has its homeland, which is the realm of the meaning of things… -Saint Exupéry The Wisdom of the Sands In the mid-1970s, curriculum theorist James Macdonald, in his discussion of various ideologies of education, proposed a category that he called the “transcendental developmental ideology.” This perspective would correct what he thought was the limiting, materialist focus of the radical or political view of education, which he considered a “hierarchical historical view that has outlived its usefulness both in terms of the emerging structure of the environment and of the psyches of people today” (Macdonald 1995, 73). The transcendental developmental ideology would embrace progressive and radical social values, according to Macdonald, but would be rooted in a deep spiritual awareness. Drawing upon the work of M.C. Richards (1989), he used the term “centering” to signify this form of consciousness. Macdonald termed his methodology of development a “dual dialectic,” a praxis involving reflective transaction between the individual ego and the inward subjective depths of the self, as well as between the ego and the outer objective structures of the environment. This method grew out of his critique of existing developmental theories (see Kohlberg and Mayer, 1972), which he thought neglected one or another aspect of this praxis, thus failing to take into account the full dimension of human “being.” Macdonald was influenced by the work of C.G.