In Sri Lanka Through Shared Memorialization of Pain and Through Such Sharing, Generate Empathy for ‘The Other’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Color Research Fellows 5-2015 Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Kimberly Kolor University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015 Part of the Asian History Commons Kolor, Kimberly, "Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of uthenticityA in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka" (2015). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Color. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 This paper was part of the 2014-2015 Penn Humanities Forum on Color. Find out more at http://www.phf.upenn.edu/annual-topics/color. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Abstract In post-conflict Sri Lanka, communal tensions continue ot be negotiated, contested, and remade. Color codes virtually every aspect of daily life in salient local idioms. Scholars rarely focus on the lived visual semiotics of local, everyday exchanges from how women ornament their nails to how communities beautify their open—and sometimes contested—spaces. I draw on my ethnographic data from Eastern Sri Lanka and explore ‘color’ as negotiated through personal and public ornaments and notions of beauty with a material culture focus. I argue for a broad view of ‘public,’ which includes often marginalized and feminized public modalities. This view also explores how beauty and ornament are salient technologies of community and cultural authenticity that build on histories of ethnic imaginaries. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS). -

Update UNHCR/CDR Background Paper on Sri Lanka

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM Sri Lanka UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, JUNE 2001 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. ISSN 1020-8410 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS.............................................................................................................................. 3 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 4 2 MAJOR POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN SRI LANKA SINCE MARCH 1999................ 7 3 LEGAL CONTEXT...................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 International Legal Context ................................................................................................. 17 3.2 National Legal Context........................................................................................................ 19 4 REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION............................................................... -

UN-Habitat Implements Disaster Risk Reduction Initiatives in Mannar Town in Sri Lanka's Northern Province

UN‐Habitat Implements Disaster Risk Reduction Initiatives in Mannar Town in Sri Lanka’s Northern Province May 2014, Mannar, Sri Lanka. The United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN‐Habitat), in collaboration with the Mannar Urban Council, is implementing a number of small scale Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) initiatives to assist communities cope with the adverse impacts of natural disasters through the Disaster Resilient City Development Strategies for four Cities in the Northern and Eastern Provinces of Sri Lanka (Phase II) Project. Funded by the Government of Australia, the project is being implemented by UN‐Habitat in the towns of Mannar, Vavuniya, Mullaitivu and Akkaraipattu in collaboration with the Local Authorities, the Ministry of Disaster Management, and Urban Development Authority (UDA), Sri Lanka Institute of Local Governance (SLILG), Institute for Construction Training and Development (ICTAD) and the University of Moratuwa. Implementing small scale DRR interventions is a key output of the Disaster Resilient Urban Planning and Development Unit that has been established at the Mannar Urban Council. The need for such DRR activities was identified by the project partners as a key priority during the implementation of Phase I during 2012‐2013. As a result, additional funding has been allocated to implement small scale DRR activities in the four cities during the second phase. Small scale infrastructure has been identified by the communities and the LAs to reduce the vulnerability to disasters of settlements and communities. In the Mannar Urban Council area, the infrastructure activities 50 Housing Scheme Road before rehabilitation identified included rehabilitation of two internal roads and laying of Hume pipes and culverts to release storm water from flood‐prone areas. -

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details District Divisional Secretariat Divisional Secretary Assistant Divisional Secretary Life Location Telephone Mobile Code Name E-mail Address Telephone Fax Name Telephone Mobile Number Name Number 5-2 Ampara Ampara Addalaichenai [email protected] Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 0672277452 Mr.MAC.Ahamed Naseel 0779805066 Ampara Ampara [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 Mr.H.S.N. De Z.Siriwardana 0632223495 0718010121 063-2222351 Vacant Vacant Ampara Sammanthurai [email protected] Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr. S.L.M. Hanifa 0672260236 0716829843 0672260293 Mr.MM.Aseek 0777123453 Ampara Kalmunai (South) [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 Mr.M.M.Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 0672224430 Vacant - Ampara Padiyathalawa [email protected] Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 0632050856 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0712508960 Ampara Sainthamarathu [email protected] Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Mr. I.M.Rikas 0752800852 0672056490 I.M Rikas 0777994493 Ampara Dehiattakandiya [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mr.R.M.N.C.Hemakumara 027-2250177 0701287125 027-2250081 Mr.S.Partheepan 0714314324 Ampara Navithanvelly [email protected] Divisional secretariat, Navithanveli, Amparai 0672224580 0672223256 MR S.RANGANATHAN 0672223256 0776701027 0672056885 MR N.NAVANEETHARAJAH 0777065410 0718430744/0 Ampara Akkaraipattu [email protected] Main Street, Divisional Secretariat- Akkaraipattu 067 22 77 380 067 22 800 41 M.S.Mohmaed Razzan 067 2277236 765527050 - Mrs. A.K. Roshin Thaj 774659595 Ampara Ninthavur Nintavur Main Street, Nintavur 0672250036 0672250036 Mr. T.M.M. -

Municipal and Urban Councils of Sri Lanka

Type of Council Province District Municipality Area (km²) Population Municipal Western Colombo Colombo 37 693,596 Municipal Western Colombo Dehiwala-Mount Lavinia 21 233,290 Municipal Western Colombo Sri Jayawardenepura Kotte 17 125,270 Municipal Western Colombo Kaduwela 87 250,668 Municipal Western Colombo Moratuwa 23 191,634 Municipal Western Gampaha Negombo 31 141,520 Municipal Western Gampaha Gampaha 38 67,990 Municipal North Western Kurunegala Kurunegala 11 31,299 Municipal Central Kandy Kandy 27 125,182 Municipal Central Matale Matale 9 48,225 Municipal Central Matale Dambulla 54 26,000 Municipal Central Nuwara Eliya Nuwara Eliya 12 35,081 Municipal Uva Badulla Badulla 10 42,066 Municipal Uva Badulla Bandarawela 27 36,778 Municipal Southern Galle Galle 17 101,159 Municipal Southern Matara Matara 13 90,000 Municipal Southern Hambantota Hambantota 83 22,978 Municipal Sabaragamuwa Ratnapura Ratnapura 20 52,000 Municipal North Central Anuradhapura Anuradhapura 36 109,175 Municipal Northern Jaffna Jaffna 20 90,279 Municipal Eastern Batticaloa Batticaloa 75 92,120 Municipal Eastern Ampara Kalmunai 23 120,000 Municipal Eastern Ampara Akkaraipattu 7 39,223 Urban Southern Galle Ambalangoda Urban Eastern Ampara Ampara Urban Sabaragamuwa Ratnapura Balangoda Urban Western Kalutara Beruwala Urban Western Colombo Boralesgamuwa Urban Northern Jaffna Chavakachcheri Urban North Western Puttalam Chilaw Urban Sabaragamuwa Ratnapura Embilipitiya 58,371 Urban Eastern Batticaloa Eravur Urban Central Kandy Gampola Urban Uva Badulla Haputale Urban Central -

Support for Professional and Institutional Capacity Enhancement (SPICE) April – June 2016 Quarterly Report Submitted to USAID/Sri Lanka

Support for Professional and Institutional Capacity Enhancement (SPICE) April – June 2016 Quarterly Report Submitted to USAID/Sri Lanka This publication was produced for review by the United States Agency for International Development. Grantee: Counterpart International Associates: Management Systems International (MSI) International Center for Not-for-Profit Law (ICNL) International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) GCSS Associate Cooperative Agreement Number: DFD-A-00-09-00141-00 Cooperative Agreement Number: AID 383-LA-13-00001 Counterpart International 2345 Crystal Drive, Suite 301 Arlington, VA 22202 Telephone: 703.236.1200 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 Operational Context 5 Achievements 5 Operational Highlights 6 Challenges 6 Programming Priorities in the Next Quarter 6 POLITICAL CONTEXT 7 ANALYSIS 8 SUMMARY OF ACTIVITIES 9 Program Administration and Management 9 Component 1. Support Targeted National Indigenous Organizations to Promote Pluralism, Rights and National Discourse and Support Regional Indigenous Organizations to Promote Responsive Citizenship and Inclusive Participation 10 Component 2. Strengthen Internal Management Capacity of Indigenous Organizations 29 Capacity Building Process for SPICE Grantees 29 Capacity-Building Support to USAID’s Development Grants Program (DGP) 30 Community Organizations’ Role and Ethos: Value Activism through Leaders’ Understanding Enhancement Support (CORE VALUES) Training 30 Civil Society Strengthening – Operational Environment and Regulatory Framework 32 PROJECT MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING -

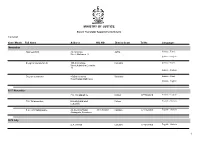

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Sri Lanka Date: 19 September 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA33744 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 19 September 2008 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Freedom of movement – Checkpoints This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Can you please provide information on the ease with which people could travel in the east and north of Sri Lanka during 2002, and also in subsequent years until 2006? 2. Please include any information about check points. RESPONSE 1. Can you please provide information on the ease with which people could travel in the east and north of Sri Lanka during 2002, and also in subsequent years until 2006? 2. Please include any information about check points. Sources indicate that travel to the north and east of Sri Lanka was possible between 2002 and 2006 due to the signing of the peace agreement between the Sri Lankan Army (SLA) and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE) in 2002. This agreement, whilst not adhered to by either party, at least reduced full scale military activity in then LTTE-held areas, -

Tides of Violence: Mapping the Sri Lankan Conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre

Tides of violence: mapping the Sri Lankan conflict from 1983 to 2009 About the Public Interest Advocacy Centre The Public Interest Advocacy Centre (PIAC) is an independent, non-profit legal centre based in Sydney. Established in 1982, PIAC tackles barriers to justice and fairness experienced by people who are vulnerable or facing disadvantage. We ensure basic rights are enjoyed across the community through legal assistance and strategic litigation, public policy development, communication and training. 2nd edition May 2019 Contact: Public Interest Advocacy Centre Level 5, 175 Liverpool St Sydney NSW 2000 Website: www.piac.asn.au Public Interest Advocacy Centre @PIACnews The Public Interest Advocacy Centre office is located on the land of the Gadigal of the Eora Nation. TIDES OF VIOLENCE: MAPPING THE SRI LANKAN CONFLICT FROM 1983 TO 2009 03 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................... 09 Background to CMAP .............................................................................................................................................09 Report overview .......................................................................................................................................................09 Key violation patterns in each time period ......................................................................................................09 24 July 1983 – 28 July 1987 .................................................................................................................................10 -

Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project – Additional Financing (RRP SRI 37381)

Dry Zone Urban Water and Sanitation Project – Additional Financing (RRP SRI 37381) DEVELOPMENT COORDINATION A. Major Development Partners: Strategic Foci and Key Activities 1. In recent years, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Government of Japan have been the major development partners in water supply. Overall, several bilateral development partners are involved in this sector, including (i) Japan (providing support for Kandy, Colombo, towns north of Colombo, and Eastern Province), (ii) Australia (Ampara), (iii) Denmark (Colombo, Kandy, and Nuwaraeliya), (iv) France (Trincomalee), (v) Belgium (Kolonna–Balangoda), (vi) the United States of America (Badulla and Haliela), and (vii) the Republic of Korea (Hambantota). Details of projects assisted by development partners are in the table below. The World Bank completed a major community water supply and sanitation project in 2010. Details of Projects in Sri Lanka Assisted by the Development Partners, 2003 to Present Development Amount Partner Project Name Duration ($ million) Asian Development Jaffna–Killinochchi Water Supply and Sanitation 2011–2016 164 Bank Dry Zone Water Supply and Sanitation 2009–2014 113 Secondary Towns and Rural Community-Based 259 Water Supply and Sanitation 2003–2014 Greater Colombo Wastewater Management Project 2009–2015 100 Danish International Kelani Right Bank Water Treatment Plant 2008–2010 80 Development Agency Nuwaraeliya District Group Water Supply 2006–2010 45 Towns South of Kandy Water Supply 2005–2010 96 Government of Eastern Coastal Towns of Ampara