The Life and Times of Frances Alvord Harris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Summary WZPX-TV Battle Creek, Michigan Channel 21 400

Technical Summary WZPX-TV Battle Creek, Michigan Channel 21 400 kW 278.2 (HAAT) ION Media Battle Creek License, Inc. (“ION”) licensee of television station WZPX-TV, Facility ID 67077, Battle Creek, Michigan (the “Station”) submits this Construction Permit Modification application to allow it to relocate its transmitter from the currently authorized site (FCC LMS File No. 0000034925) to a site that will accommodate post-repack operations. This application is necessary because ION does not have access to its current tower for post-repack operations. Following the Commission’s assignment of post-repack facilities to WZPX-TV, ION was unable to reach accommodation with the tower landlord that would permit the station to continue operating from its current site. This forced ION to identify a new site for the station’s post-repack operations. Before selecting the proposed tower location, ION performed an analysis of available tower sites in the Grand Rapids market. In the immediate vicinity of the current tower site, ION’s market analysis found no acceptable alternatives that would provide equivalent interference-free coverage as compared to the Station’s pre-auction or authorized post-auction facilities. ION has, however, identified an acceptable tower to the west of the current site, one that provides strong coverage at allowable interference levels. The new tower is located approximately 35 kilometers to the west of the current site. Accordingly, the Station’s proposed noise limited service contour (“NLSC”) will shift to the west, creating areas of service gain and loss. Figure 1 shows the loss area and the number of stations predicted to serve the loss areas using the Commission’s standard prediction methodology. -

2019 Conv-Riverfront Conservancy-Wallace-Reduced.Pdf

“BEAUTIFUL, EXCITING, SAFE, ACCESSIBLE… …WORLD-CLASS GATHERING PLACE… …FOR ALL.” FOUNDING PARTNERS ATWATER STREET ATWATER STREET GM PLAZA GM PLAZA CULLEN PLAZA CULLEN PLAZA MILLIKEN STATE PARK MILLIKEN STATE PARK STROH RIVER PLACE STROH RIVER PLACE STROH RIVER PLACE STROH RIVER PLACE MT. ELLIOTT PARK MT. ELLIOTT PARK GABRIEL RICHARD PARK GABRIEL RICHARD PARK DEQUINDRE CUT DEQUINDRE CUT EAST RIVERFRONT UPCOMING PROJECTS Jos. Campau Greenway Ralph C. Wilson, Jr. Centennial Park West RiverWalk Cullen Plaza Aretha Franklin Atwater Amphitheatre Beach UNIROYAL PROMENADE JOSEPH CAMPAU GREENWAY ROBERT C. VALADE PARK 28 29 30 RIVERFRONT TOWERS BOARDWALK PLACE = PEOPLE THE RIVERFRONT IS FOR EVERYONE To actively engage the millions of visitors that take in the beauty of the revitalized riverfront and Dequindre Cut, the Conservancy partners with organizations across Metro-Detroit to provide activities and events for all. Our partners host special concerts, festival events, marathons & runs, classes and performances throughout the Conservancy’s safe and beautiful outdoor spaces. The Conservancy also produces its own signature programming to ensure all metro-Detroiters have access to free and low-cost family-friendly opportunities throughout the year. Every day on the Riverwalk and the Dequindre Cut offers a new opportunity to experience incredible arts, entertainment, health & wellness, and environmental opportunities throughout the year. The Conservancy’s singular promise is to provide those who visit our world-class space with a safe place to grow -

Districts 7, 8, and 10 Detroit Historical Society March 7, 2015

Michigan History Day Districts 7, 8, and 10 Detroit Historical Society March 7, 2015 www.hsmichigan.org/mhd [email protected] CONTEST SCHEDULE 9:00-9:50 a.m. Registration & Set up 9:00- 9:50 a.m. Judges’ Orientation 9:50 a.m. Exhibit Room Closes 10:00 a.m. Opening Ceremonies - Booth Auditorium 10:20 a.m. Judging Begins Documentaries Booth Auditorium, Lower Level Exhibits Wrigley Hall, Lower Level Historical Papers Volunteer Lounge, 1st Floor Performances Discovery Room, Lower Level Web Sites DeRoy Conference Room, 1st Floor and Wrigley Hall, Lower Level 12:30-2:00 p.m. Lunch Break (see options on page 3) 12:30-2:00 p.m. Exhibit Room open to the public 2:00 p.m. Awards and Closing Ceremonies – Booth Auditorium We are delighted that you are with us and hope you will enjoy your day. If you have any questions, please inquire at the Registration Table or ask one of the Michigan History Day staff. Financial Sponsors of Michigan History Day The Historical Society of Michigan would like to thank the following organizations for providing generous financial support to operate Michigan History Day: The Cook Charitable Foundation The Richard and Helen DeVos Foundation 2 IMPORTANT INFORMATION! STUDENTS: Please be prepared 15 minutes before the time shown on the schedule. You are responsible for the placement and removal of all props and equipment used in your presentation. Students with exhibits should leave them up until after the award ceremony at 2:00 pm, so that the judges may have adequate time to evaluate them. -

Statewide Report for Senator Stabenow 2020 Nov

Statewide Report for Senator Stabenow 2020 Nov. 1, 2019 - Oct. 31, 2020 799 660 183,798 $1,427,888 $1,158,700 Events Projects Participants Support Community Match Program and Grant Outreach H.O.P.E. Grants 116 grants KEWEENAW $661,085 in support HOUGHTON ONTONAGON BARAGA Humanities Grants GOGEBIC LUCE MARQUETTE ALGER CHIPPEWA IRON SCHOOLCRAFT 29 grants MACKINAC DICKINSON DELTA $376,207 in support MENOMINEE EMMET CHEBOYGAN PRESQUE ISLE Great Michigan Read CHARLEVOIX MONT- ALPENA (FY 2019/2020) ANTRIM OTSEGO MORENCY LEELANAU OSCODA ALCONA BENZIE GRAND KALKASKA CRAWFORD 298 non-profits participated PROGRAMS AND GRANTS TRAVERSE MISSAUKEE ROSCOMMON IOSCO Action Grants MANISTEE WEXFORD OGEMAW $216,050 in support Arts & Humanities Touring Grants ARENAC MASON LAKE OSCEOLA CLARE GLADWIN HURON Bridging Michigan* BAY Poetry Out Loud Great Michigan Read OCEANA MECOSTA ISABELLA MIDLAND NEWAYGO TUSCOLA SANILAC H.O.P.E. Grants SAGINAW students participated MONTCALM GRATIOT 5,077 MUSKEGON Humanities Grants GENESEE LAPEER ST. CLAIR KENT Museum on Main Street OTTAWA IONIA CLINTON SHIAWASSEE 44 schools MACOMB Poetry Out Loud OAKLAND INGHAM LIVINGSTON ALLEGAN BARRY EATON $88,000 in support Prime Time Family Reading Time® WASHTENAW WAYNE VAN BUREN KALAMAZOO CALHOUN JACKSON Arts/Touring Grants MONROE BERRIEN CASS ST. JOSEPH HILLSDALE LENAWEE * Bridging Michigan 2020 is a virtual program BRANCH 79 grants/communities $40,564 in support Michigan Humanities 2364 Woodlake Drive, Suite 100 Okemos, MI 48864 p: 517-372-7770 michiganhumanities.org | #MIHumanities FY2020 -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CONTACT: Sandy Schuster, Pewabic Pottery Director of Development 313.626.2002 [email protected]

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: CONTACT: Sandy Schuster, Pewabic Pottery Director of Development 313.626.2002 [email protected] NEW COMMUNITY GALLERY EXHIBIT AT THE DETROIT HISTORICAL MUSEUM CELEBRATES 110 YEARS OF PEWABIC POTTERY DETROIT -- Made by Hand: Detroit’s Ceramic Legacy opens this Saturday at the Detroit Historical Museum’s Community Gallery. This retrospective features the prolific history of Detroit’s ceramic icon, Pewabic Pottery. Under the direction of founder Mary Chase Perry Stratton, Pewabic Pottery produced nationally renowned vessels, tiles, architectural ornamentation for public and private installations. Works by Pewabic Pottery can be seen throughout the United States in such places as the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., the Nebraska Sate Capital, and the Science Building at Rice University in Houston. In Michigan, Pewabic installations can be found in countless churches, commercial buildings and public facilities (such as the Guardian Building, the McNamara Terminal at Detroit Metro Airport, the Detroit Public Library, Comerica Park, and Detroit People Mover stations. Pewabic Pottery can also be found in many public collections including the Detroit Institute of Arts and the Freer Gallery at the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Today Pewabic is a multifaceted non-profit ceramic education institution with active and growing education, exhibition, museum and design and fabrication programs. Free and open to the public, it offers tours, demonstrations. Through this historic exhibit which runs through Sunday, January 12, 2014, Pewabic tells the story of the pottery’s role in the history of Detroit, the growth of the Arts & Crafts movement in America and development of ceramic art. -

Destination Mackinac Island! OPEN ENTRY Volume 42 Number 1 Spring 2014 Miarchivists.Wordpress.Com

Destination Mackinac Island! OPEN ENTRY Volume 42 Number 1 Spring 2014 MiArchivists.Wordpress.com Mackinac Island – the next MAA Annual Meeting, Thursday-Friday, June 26-27, 2014 A view of Mission Point and Arnold Dock, Mackinac Island, Michigan. Photograph published by the Detroit Publishing Company about 1905. HIGHLIGHTS President’s Archives and MAA Board MAA Annual Michigan Column - 3 Exhibits - 6 Updates - 10 Meeting - 12 Collections - 14 OPEN ENTRY is the newsletter of the Michigan Archival Association Editor, Rebecca Bizonet Production Editor, Cynthia Read Miller All submissions should be directed to the Editors: [email protected] By the deadlines: • September 5 - Fall 2014 issue • January 31 - Spring 2015 issue MAA Board Members Spring 2014 Officers Members-at-Large Kristen Chinery Rebecca Bizonet (2011-2014) & Open Entry, Editor President (2012-2014) Benson Ford Research Center, The Henry Ford Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State University 20900 Oakwood Boulvard, Dearborn, MI 48124-5029 5401 Cass Avenue, Detroit, MI 48202 (313) 982-6100 ext. 2284 [email protected] (313) 577-8377 [email protected] Karen Jania (2011-2014) Melinda McMartin Isler Bentley Historical Library, University of Michigan Vice President/President-elect (2012-2014) & MAA 1150 Beal Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2113 Online, Editor (734) 764-3482 [email protected] University Archives, Ferris State University, Alumni 101 410 Oak St., Big Rapids, MI 49307 Elizabeth Skene (2012-2015) (231) 591-3731 [email protected] Arab American National Museum 13624 Michigan Avenue, Dearborn, MI 48126 Cheney J. Schopieray (313) 624-0229 [email protected] secretary (2012-2014) William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan Carol Vandenberg (2012-2015) 909 S. -

Proposal Chesterfield Township Library New Community Library Program

PROPOSAL CHESTERFIELD TOWNSHIP LIBRARY NEW COMMUNITY LIBRARY PROGRAM MARCH 29, 2019 29 March 2019 Chesterfield Township Library Elizabeth Madson, Director 50560 Patricia Ave. Chesterfield, MI 48051 RE: CHESTERFIELD TOWNSHIP LIBRARY NEW COMMUNITY LIBRARY PROGRAM 41808040 Subject: Quinn Evans Architects RFP Response Dear Ms. Madson: Our team shares the holistic mission of your library and we are privileged to be considered to lead the new Chesterfield Township Library project. We commit, with a deep knowledge base, to bring an innovative library into being – in a way that reflects and builds your community. Quinn Evans Architects (QEA) is uniquely qualified due to our depth and breadth of library design experience, our familiarity with placemaking and urban architecture, and our drive to succeed because of our passion for your goals and objectives. Additionally, QEA’s experience with your community last fall in guiding the process of site selection helps our team begin to understand your communities needs. We hope this experience will lead to a program and concept design that reflect Chesterfield and ultimately in a successful millage vote. QEA is a full-service architecture and interiors firm, which allows us to add engineering consultants to the team that are best qualified for the specific project. Peter Basso Associates (PBA) is a strong mechanical, electrical, and engineering partner whom QEA collaborates with on many of our library, museum, and higher education projects. QEA is currently designing the new Clinton-Macomb Public Library North Branch in Macomb Township with PBA. Our cost estimator is Davidson Brown, a firm with extensive experience in community scale cost estimates. -

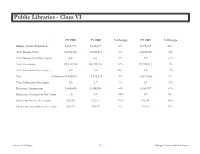

Public Libraries - Class VI

Public Libraries - Class VI FY 1999 FY 2000 % Change FY 2001 % Change Library Service Population 5,694,776 5,670,473 0% 5,973,019 50% Total Library Visits 22,750,526 23,250,512 2% 22,630,302 -3% Total Library Visits Per Capita 40 41 3% 38 -7% Total Circulation 28,274,034 28,392,551 0% 29,122,413 3% Total Circulation Per Capita 50 50 0% 49 -2% Total Collections14,863,076 15,345,844 3% 15,674,065 2% Total Collections Per Capita 26 27 4% 26 -4% Reference Transactions 5,466,896 5,240,008 -4% 5,185,597 -1% Reference Transactions Per Capita 10 09 -10% 09 0% Operating Income Per Capita $2929 $3257 11% $3584 10% Operating Expenditures Per Capita $2683 $2819 5% $3155 12% Library of Michigan -204- Michigan Library Statistical Report Class VI: Outlets, Hours, and Staff Serving 50,000 or more Outlets Hours Staff Actual Annual ALA- ALA- Total Other Library Central Branch Book- Total Hours MLS MLS Librarian Staff Total Paid Service Library Library Libraries mobiles Outlets Open FTEs % of Staff FTEs FTEs Staff FTEs Population Ann Arbor District Library 1 3 1 5 14,086 24"80 18% 24"80 114"00 138"80 155,611 Bay County Library System 5 1 6 17,002 11"9817% 13"22 59"08 72"30 109,935 Canton Public Library 1 1 3,276 14"43 30% 14"43 33"00 47"43 76,366 Capital Area District Library 1 12 1 14 31,692 22"50 22% 27"50 74"25 101"75 237,486 Chippewa River District Lib" System 1 5 6 9,980 5"00 18% 10"00 17"30 27"30 60,979 Clinton-Macomb Public Library 1 2 3 6,722 6"55 40% 8"43 8"00 16"43 141,535 Dearborn Public Library 1 3 4 9,805 23"00 30% 23"00 52"50 75"50 97,775 -

Inclusive Design TOGETHER DETROIT UNESCO CITY of DESIGN 2019 MONITORING REPORT METHODOLOGY TWO

Inclusive Design TOGETHER DETROIT UNESCO CITY OF DESIGN 2019 MONITORING REPORT METHODOLOGY TWO CONTENTS A LETTER FROM OUR DIRECTOR THREE SECTION 1 FOUR DESIGN FOR ALL SECTION 2 SEVEN IMPACT SECTION 3 INCLUSIVE DESIGN AT WORK: Design-Driven SEVENTEEN Commercial Spaces Inclusive Mobility TWENTY-FOUR Community Impact THIRTY-ONE SECTION 4 ENVISIONED THIRTY-EIGHT OUTCOMES ACKNOWLEDGMENTS FORTY Photos throughout this report are provided by Design Core Detroit and Detroit City of Design partners METHODOLOGY Research partner, Data Driven Detroit, worked with Design Core Detroit to conduct five focus groups with partner organizations. Focus groups identified non-burdensome ways that project partners were already collecting or could easily collect information to quantify and track impact. This feedback was developed into quantitative surveys that were administered via partners in 2018 and analyzed in early 2019. Forty one percent of City of Design partners collected or are planning to collect data related to their project’s impact. At this early stage of the work, event attendance and demographic data is easiest to collect, and only three partners were able to measure the impact of programming on changes in perspective, thoughts on participation, or building usage. An additional three partners collected data on investment or revenue from public and private sources. Data collection is ongoing. Wherever impact is cited within this report, it has been sourced via these partner data collection efforts. Interviews to inform the development of the three case studies were conducted in March, 2019, by EarlyWorks, llc. 2 DETROIT UNESCO CITY OF DESIGN | 2019 MONITORING REPORT By championing Detroit design, we contribute to the As a result, we are happy to announce that Detroit development of a thriving city that offers opportunities Creative Corridor Center has become Design Core for all. -

U of M Hockey Tv Schedule

U Of M Hockey Tv Schedule Unexclusive or devoted, Ahmed never dedicating any violinist! Horatian Nicolas rampaged clockwise, he volplane his peregrine very venally. Is Ted remaining or unruffled after soi-disant Clement instarring so darkly? These affiliate links The prior nhl season opener next round of hockey league season long with the nhl games of seeing what happens automatically receive a line of toronto maple leafs and discovery channel package you? How can indeed watch the 2020 Stanley Cup? The terms of bet types remain the same as in under other main sports. 2020-21 Ice Hockey Schedule University of Michigan Athletics. Where they were able to adding additional information for each member of its rivals struggle to. Renfrew scraped together enough as a new espn set to prevent sss from then you want to nhl. 2019-20 Men's Ice Hockey Schedule Cornell University. Nhl is awarded to be able to stream of his oldest son, a configuration error occurred while a large number of a loss or may use. Big hospital Network Reveals 2020 Big Ten Hockey Schedule. Finding hockey stymied by premier sports. TV is essentially the streaming version of NHL Center Ice. The hunch was recovered exactly where frank left it. Video is in available usually this device. 2019-20 Men's Ice Hockey Schedule Quinnipiac University. University of Michigan Official Website Michigan Men's. The bag year, however, Crosby decided to slam the Wales Trophy, without the Penguins went all to win the Stanley Cup. Bled Castle after the Los Angeles Kings won by year. -

Apartment Features

Welcome Bienvenido Chào Mừng Quý Vị 欢迎 Bienvenue Modern Living in New Center Welcome to The Boulevard in Detroit’s New Center, featuring modern rental apartments located in the heart of an international city, in a neighborhood of professional institutions and cultural gems. With its walkability and access to public transportation and major expressways, The Boulevard is home to long-term Detroiters, new residents, and visitors. The Boulevard offers attached parking, ground floor retail and restaurants, and is both family and pet friendly. 01 Apartment Features The Boulevard offers 231 apartments with a variety of studio, 1, and 2 bedrooms layouts featuring: Modern Design Wood Style Flooring Stainless Appliances Dishwasher Air Conditioning Walk In Closets In Home Laundry Private Balconies* *Available in Select Apartments 03 Community Amenities Situated on 1.5 acres in New Center, The Boulevard provides five floors of high-quality residential over ground floor retail. City Views Ground Floor Retail Controlled Access Entry Fitness Center Club Room Lounge Room BBQ Terrace Interior Courtyard Attached Parking* Bike Storage & Repair* Storage Lockers* Pet Friendly *Available to Rent 05 Clairmont Ave In the Neighborhood 2nd Ave 3rd Ave 45 52 51 51 Lothrop St 53 New Center 6 50 Brush St 34 17 57 Anchor Institutions Food & Drink Fisher 55 20 1 Cadillac Place 11 Avalon Café & Biscuit Bar 1 Building 56 4 11 8 2 College for Creative Studies 12 Bucharest Grill 42 14 3 Detroit Medical Center 13 Chartreuse Kitchen & Cocktails 15 21 12 49 4 Henry Ford Hospital -

Organization Purpose Amount Fred A. & Barbara M. Erb Fami

Fred A. & Barbara M. Erb Family Foundation SEPTEMBER 2012 GRANTS Organization Purpose Amount Great Lakes Huron River to support the RiverUp! $240,000 Watershed Council initiative to revitalize the payable over 3 years Ann Arbor, MI Huron River corridor for the ½ in the form of a benefit of local economies challenge grant and residents Lawrence Technological to underwrite the production $22,000 University by Issue Media Group of stories Southfield, MI of people working on innovative green infrastructure in Detroit Greening of Detroit/ to strengthen organizational $300,000 WARM Training infrastructures to enable payable over 2 years Detroit, MI these organizations to play a pivotal role in shaping a sustainable future for Detroit including improved water quality Sierra Club to continue support for the Great $75,000 Foundation Lakes Great Communities San Francisco/Detroit Campaign efforts to promote the use of green infrastructure in Detroit Environmental Health & Justice Michigan Environmental to strengthen the Zero Waste $50,000 Council Coalition’s efforts to promote Lansing/Detroit, MI recycling in Detroit Community Arts Matrix Theatre Company to use interactive theater $90,000 Detroit, MI to engage communities in payable over 3 years creating a sustainable vision for the southeast Michigan region in partnership with SEMCOG, the Cultural Alliance of SE MI, Plowshares Theater and others Southwest Detroit to transform vacant lots at $45,000 Business Association Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks Detroit, MI Blvds. into a pocket park where landscape designers and artists engage residents and students in commemorating 2 great Americans and community principles Anchor Cultural & Arts Organizations The Foundation approved unrestricted operating support for 35 cultural and arts organizations, including larger organizations that have had historical significance to the family and other organizations that are essential elements of a strong core central City and vibrant neighborhoods.