Rebecca Belmore and the Aesthetico-Politics of “Unnameable Affects”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Performing Power

Rebecca Belmore: Performing Power Jolene Rickard The aurora borealis or northern lights, ignited by the intersection of elements at precisely the right second, burst into a fire of light on black Anishinabe nights. For some, the northern lights are simply reflections caused by hemispheric dust, but for others they are power. Rebecca Belmore knows about this power; her mother, Rose, told her so.1 Though the imbrication of Anishinabe thinking was crucial in her formative years in northern Ontario, Belmore now has a much wider base of observation from Vancouver, British Columbia. Her role as 2 transgressor and initiator—moving fluidly in the hegemony of the west reformulated as "empire " —reveals how conditions of dispossession are normalized in the age of globalization. Every country has a national narrative, and Canada is better than most at attempting to integrate multiple stories into the larger framework, but the process is still a colonial project. The Americas need to be read as a colonial space with aboriginal or First Nations people as seeking decolonization. The art world has embraced the notion of transnational citizens, moving from one country to the next by continuously locating their own subjectivities in homelands like China, Africa and elsewhere. As a First Nations or aboriginal person, Belmore's homeland is now the modern nation of Canada; yet, there is reluctance by the art world to recognize this condition as a continuous form of cultural and political exile. The inclusion of the First Nations political base is not meant to marginalize Belmore's work, but add depth to it. -

Brian Jungen Friendship Centre

BRIAN JUNGEN FRIENDSHIP CENTRE Job Desc.: AGO Access Docket: AGO0229 Client: AGO A MESSAGE FROM Supplier: Type Page: STEPHAN JOST, Trim: 8.375" x 10.5" Bleed: MICHAEL AND SONJA Live: Pub.: Membership Mag ad KOERNER DIRECTOR, Colour: CMYK Date: April 2019 AND CEO Insert Date: Ad #: AGO0229_FP_4C_STAIRCASE DKT./PROJ: AGO0229 ARTWORK APPROVAL Artist: Studio Mgr: Production: LESS EQUALS MOREProofreader: Creative Dir.: Art Director: Copywriter: The AGO is having a moment. There’s a real energy when I walkTranslator: through the galleries, thanks to the thousands of visitors who have experienced the AGOAcct. for Service: the first time – or their hundredth. It is an energy that reflects our vibrant and diverseClient: city, and one that embraces the undeniable power of art to change the world. And weProof: want 1 more2 3 4people 5 6 to7 Final experience it and make the AGO a habit. PDFx1a Laser Proof Our membership is generous and strong. Because of your support, on May 25 we’re launching a new admission model to remove barriers and encourage deeper relationships with the AGO. The two main components are: • Everyone 25 and under can visit for free • Anyone can purchase a pass for $35 and visit as many times as they’d like for a full year Without your vital support as an AGO Member, this new initiative wouldn’t be possible. Thanks to you, a teenager might choose us to impress their date or a tired dad might take his children for a quick 30-minute visit, knowing he can come back again and again. You will continue to enjoy the special benefits of membership, including Members’ Previews that give you first access to our amazing exhibitions. -

About Humanity, Not Ethnicity? Transculturalism, Materiality, and the Politics of Performing Aboriginally on the Northwest Coast

ABOUT HUMANITY, NOT ETHNICITY? TRANSCULTURALISM, MATERIALITY, AND THE POLITICS OF PERFORMING ABORIGINALLY ON THE NORTHWEST COAST by ALICE MARIE CAMPBELL B.A. (hons), The University of British Columbia, 2001 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Anthropology and Sociology) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2004 ©Alice Marie Campbell, 2004 THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Library Authorization In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Alice Marie Campbell 23/08/04 Name of Author (please print) Date (dd/mm/yyyy) Title of Thesis: About Humanity, Not Ethnicity?: Transculturalism, Materiality, and the Politics of Performing Aboriginality on the Northwest Coast Degree: Master of Arts Year: 2004 Department of Anthropology and Sociology The University of British Columbia Vancouver, BC Canada grad.ubc.ca/forms/?formlD=THS page 1 of 1 last updated: 23-Aug-04 Abstract In this multi-sited thesis based on ethnographic fieldwork conducted from 2002-2004, I examine how the transcultural production of Northwest Coast material culture subverts the hegemonic, discursive, and traditionalist constructions of 'Aboriginality' that have isolated Northwest Coast artists from the contemporary art world (Duffek 2004). -

Gail Gallagher

Art, Activism and the Creation of Awareness of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG); Walking With Our Sisters, REDress Project by Gail Gallagher A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Faculty of Native Studies University of Alberta © Gail Gallagher, 2020 ABSTRACT Artistic expression can be used as a tool to promote activism, to educate and to provide healing opportunities for the families of missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls (MMIWG). Indigenous activism has played a significant role in raising awareness of the MMIWG issue in Canada, through the uniting of various Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. The role that the Walking With Our Sisters (WWOS) initiative and the REDress project plays in bringing these communities together, to reduce the sexual exploitation and marginalization of Indigenous women, will be examined. These two commemorative projects bring an awareness of how Indigenous peoples interact with space in political and cultural ways, and which mainstream society erases. This thesis will demonstrate that through the process to bring people together, there has been education of the MMIWG issue, with more awareness developed with regards to other Indigenous issues within non-Indigenous communities. Furthermore, this paper will show that in communities which have united in their experience with grief and injustice, healing has begun for the Indigenous individuals, families and communities affected. Gallagher ii DEDICATION ka-kiskisiyahk iskwêwak êkwa iskwêsisak kâ-kî-wanihâyahkik. ᑲᑭᐢ ᑭᓯ ᔭ ᐠ ᐃᐢ ᑫᐧ ᐊᐧ ᕽ ᐁᑲᐧ ᐃᐢ ᑫᐧ ᓯ ᓴ ᐠ ᑳᑮᐊᐧ ᓂᐦ ᐋᔭᐦ ᑭᐠ We remember the women and girls we have lost.1 1 Cree Literacy Network. -

Jim Drobnick (Updated February 2018)

Curriculum Vitae Jim Drobnick (updated February 2018) Associate Professor Contemporary Art and Theory Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences OCAD University [email protected] EDUCATION 2006 Doctor of Philosophy. Humanities Doctoral Program, Concordia University, Montreal. Thesis title: Olfactory Dimensions in Modern and Contemporary Art. Nominated for the Governor General’s Gold Medal. 1986 Master of Fine Arts. Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, Halifax. 1981 Bachelor of Arts. Oberlin College, Oberlin, Ohio. Combined Major in Art History and Studio Art. Summa cum laude. Phi Beta Kappa. POSITIONS HELD 2006-Date Associate Professor, Contemporary Art and Theory, Faculty of Liberal Arts and Sciences, OCAD University, Toronto. 2012-Date Founder and Editor (with Jennifer Fisher), Journal of Curatorial Studies, Intellect Publishers, Bristol, UK. 2006-Date Exhibition Reviews Editor, The Senses & Society, triannual, Bloomsbury Publishing, London, UK. 2010-Date Exhibition Reviews Editor, PUBLIC: Art/Culture/Ideas, biannual, Toronto. 1994-Date Founder (with Jennifer Fisher), DisplayCult, curatorial collective. 2017-Date Research Associate, Scent Art Net: Olfactory Art in the New Millennium, https://scentart.net/. 2014-Date Research Associate, EDGE Lab (Experiential Design and Gaming Environments), Responsive Ecologies, Ryerson University, Toronto. 1998-Date Research Associate, CONSERT (Concordia Sensoria Research Team), Concordia University, Montreal. 1 2016-2017 Graduate Program Director, MA Program in Contemporary Art, Design and New Media Art Histories, Ontario College of Art & Design University, Toronto. 2009-2012 Graduate Program Director, MA Program in Contemporary Art, Design and New Media Art Histories, Ontario College of Art & Design University, Toronto. 2005-2006 Research Fellow/Visiting Scholar, Art History and Visual Studies, The School of Arts, Histories and Cultures, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK. -

The National Inquiry Into the Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women of Canada: a Probe in Peril

THE NATIONAL INQUIRY INTO THE MISSING AND MURDERED INDIGENOUS WOMEN OF CANADA: A PROBE IN PERIL by Jenna Walsh INTRODUCTION discrepancy is indicative of the many operational difficulties that Throughout public spaces across Canada, red dresses have been have skewed national data sets relevant to Aboriginal victims. hung devoid of embodiment: the haunting vacancy serving Although Indigenous women are more likely to be victims of to ‘evoke a presence through the marking of an absence’.1 The violence than their non-Indigenous counterparts, the scope of this REDress project’s creator, Jaime Black, has deemed her work an violence is not easily quantified. This is, in part, due to inconsistent aesthetic response to current socio-political frameworks that police practice in collecting information on Aboriginal identity, normalise gendered and racialised violence against Aboriginal as well as under-reporting due to strained relationships between women across Canada. Her objective is to facilitate discussion police and Indigenous communities. As a result, no definitive surrounding the thousands of Indigenous women that have been statistics can be given. missing or murdered in the last four decades, while providing a visual reminder of the lives that have been lost. Black’s efforts are Despite under-reporting, the recorded figures are still alarming. one of the many grassroots initiatives that have prompted collective Although accounting for only four per cent of the national calls for a federal response to the crisis. These calls have, at last, population, Aboriginal women represent 16 per cent of Canadian been answered. In September 2016, the Government of Canada female homicide victims.4 Consequently, Indigenous women are launched a two-year Independent National Inquiry into the missing at least 4.5 times more likely to be murdered than non-Indigenous and murdered Aboriginal women and girls across the country, women across the country. -

Une Bibliographie Commentée En Temps Réel : L'art De La Performance

Une bibliographie commentée en temps réel : l’art de la performance au Québec et au Canada An Annotated Bibliography in Real Time : Performance Art in Quebec and Canada 2019 3e édition | 3rd Edition Barbara Clausen, Jade Boivin, Emmanuelle Choquette Éditions Artexte Dépôt légal, novembre 2019 Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec Bibliothèque et Archives du Canada. ISBN : 978-2-923045-36-8 i Résumé | Abstract 2017 I. UNE BIBLIOGraPHIE COMMENTÉE 351 Volet III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 I. AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGraPHY Lire la performance. Une exposition (1914-2019) de recherche et une série de discussions et de projections A B C D E F G H I Part III 1.11– 15.12. 2017 Reading Performance. A Research J K L M N O P Q R Exhibition and a Series of Discussions and Screenings S T U V W X Y Z Artexte, Montréal 321 Sites Web | Websites Geneviève Marcil 368 Des écrits sur la performance à la II. DOCUMENTATION 2015 | 2017 | 2019 performativité de l’écrit 369 From Writings on Performance to 2015 Writing as Performance Barbara Clausen. Emmanuelle Choquette 325 Discours en mouvement 370 Lieux et espaces de la recherche 328 Discourse in Motion 371 Research: Sites and Spaces 331 Volet I 30.4. – 20.6.2015 | Volet II 3.9 – Jade Boivin 24.10.201 372 La vidéo comme lieu Une bibliographie commentée en d’une mise en récit de soi temps réel : l’art de la performance au 374 Narrative of the Self in Video Art Québec et au Canada. Une exposition et une série de 2019 conférences Part I 30.4. -

Seattle Art Fair and Gagosian Announce Chris Burden's Scale

Seattle Art Fair and Gagosian Announce Chris Burden’s Scale Model of the Solar System (1983) Added To Fair’s Special Programming (SEATTLE, WA — July 26, 2018) — The Seattle Art Fair, presented by AIG, is pleased to announce an additional installation by legendary conceptual artist Chris Burden has been added to this year’s on-site programming. Presented by Gagosian, Burden’s 1983 work Scale Model of the Solar System invites fairgoers and the local Seattle community on a fun, artistic scavenger hunt around the city. The artwork will be on view during the fair’s run from August 2-5 at CenturyLink Field and beyond. Burden’s Scale Model of the Solar System (1983) begins in Gagosian’s Booth #A09 at the Seattle Art Fair, where a model of the sun (13 inches in diameter) will hang from the ceiling. Using the scale of 1 inch : 4.2 trillion inches, display cases around the fair will contain three other planets—Mercury, Venus, and Earth—each in proportion to their actual size and arranged according to their proportional distance from one another in space. The other planets are positioned around the city, leading participants on a walking tour of Seattle, culminating almost a mile away at the Seattle Art Museum, where Pluto (which was still considered a planet in 1983) will be on display. The Gagosian booth will distribute a free map for Seattle Art Fair visitors to explore the solar system. The site-specific installation joins the diverse program of daily talks, special projects, and performances curated by the Seattle Art Fair’s Artistic Director, Nato Thompson. -

Stop(The)G Ap: International Indigenous Art in Motion

Stop(the)Gap: International Indigenous art in motion Stop(the)Gap: International Indigenous art in motion Education Resource Acknowledgements Education Resource written by John neylon, art writer, curator and art museum/education consultant. The writer acknowledges the particular contribution of Brenda L Croft, Erica Green and Emma Epstein, and that of the Samstag Museum of Art staff, the participating artists and advisory curators. Published by the Anne & Gordon Samstag Museum of Art University of South Australia GPo Box 47, Adelaide SA 500 T 08 8300870 E [email protected] W unisa.edu.au/samstagmuseum Copyright © the author, artists, and University of South Australia All rights reserved. The publisher grants permission for this Education Resource to be reproduced and/or stored for twelve months in a retrieval system, transmitted by means electronic, mechanical, photocopying and/or recording only for education purposes and strictly in relation to the exhibition Stop(the)Gap: International Indigenous art in motion, at the Samstag Museum of Art. ISBn 978-0-980775-5-6 Samstag Museum of Art Director: Erica Green Curator: Exhibitions and Collections: Emma Epstein/Stephen Rainbird Coordinator: Scholarships and Communication: Rachael Elliott Samstag Administrator: Jane Wicks Helpmann Academy Intern: Lara Merrington Graphic Design: Sandra Elms Design Cover image: Warwick THORNTON, Stranded (detail), 0 film still, commissioned by Adelaide Film Festival Investment Fund 011, © the artist Stop(the)Gap: International Indigenous art in motion -

Proquest Dissertations

Redressing Femininity: Power and Pleasure in Dresses by Jana Sterbak and Cathy Daley by Catherine Ann Laird, B.Hum A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History: Art and Its Institutions Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario September, 2009 © 2009, Catherine Ann Laird Library and Archives Bibliothgque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'6dition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-58451-4 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-58451-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ______

Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today ___________________________________________________________________________________________________ A Knowledge and Literature Review Prepared for the Research and Evaluaon Sec@on Canada Council for the Arts _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ FRANCE TRÉPANIER & CHRIS CREIGHTON-KELLY December 2011 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________________ For more information, please contact: Research and Evaluation Section Strategic Initiatives 350 Albert Street. P.O. Box 1047 Ottawa ON Canada K1P 5V8 (613) 566‐4414 / (800) 263‐5588 ext. 4261 [email protected] Fax (613) 566‐4430 www.canadacouncil.ca Or download a copy at: http://www.canadacouncil.ca/publications_e Cette publication est aussi offerte en français Cover image: Hanna Claus, Skystrip(detail), 2006. Photographer: David Barbour Understanding Aboriginal Arts in Canada Today: A Knowledge and Literature Review ISBN 978‐0‐88837‐201‐7 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS! 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY! 4 Why a Literature Review?! 4 Steps Taken! 8 Two Comments on Terminology! 9 Parlez-vous français?! 10 The Limits of this Document! 11 INTRODUCTION! 13 Describing Aboriginal Arts! 15 Aboriginal Art Practices are Unique in Canada! 16 Aboriginal Arts Process! 17 Aboriginal Art Making As a Survival Strategy! 18 Experiencing Aboriginal Arts! 19 ABORIGINAL WORLDVIEW! 20 What is Aboriginal Worldview?! 20 The Land! 22 Connectedness! -

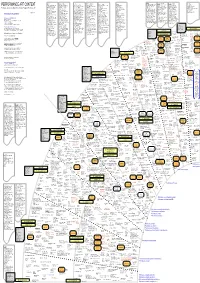

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles