Pittsburgh Wash House & Public Baths

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHLF News Publication

Protecting the Places that Make Pittsburgh Home Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation Nonprofit Org. 1 Station Square, Suite 450 U. S. Postage Pittsburgh, PA 15219-1134 PAID www.phlf.org Pittsburgh, PA Address Service Requested Permit No. 598 PHLF News Published for the members of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation No. 160 April 2001 Landmarks Launches Rural In this issue: 4 Preservation Program Landmarks Announces Its Gift Annuity Program Farms in Allegheny County—some Lucille C. Tooke Donates vent non-agricultural development. with historic houses, barns, and scenic Any loss in market value incurred by 10 views—are rapidly disappearing. In Historic Farm Landmarks in the resale of the property their place is urban sprawl: malls, Through a charitable could be offset by the eventual proceeds The Lives of Two North Side tract housing, golf courses, and high- remainder unitrust of the CRUT. Landmarks ways. According to information from (CRUT), long-time On December 21, 2000, Landmarks the U. S. Department of Agriculture, member Lucille C. succeeded in buying the 64-acre Hidden only 116 full-time farms remained in Tooke has made it Valley Farm from the CRUT. Mrs. Tooke 12 Allegheny County in 1997. possible for Landmarks is enjoying her retirement in Chambers- Revisiting Thornburg to acquire its first farm burg, PA and her three daughters are property, the 64-acre Hidden Valley excited about having saved the family Farm on Old State Road in Pine homestead. Landmarks is now in the 19 Township. The property includes a process of selling the protected property. Variety is the Spice of Streets house of 1835 that was awarded a “I believe Landmarks was the answer Or, Be Careful of Single-Minded Planning Historic Landmark plaque in 1979. -

The Arch and Colonnade of the Manhattan Bridge Approach and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 25, 1975, Number 3 LP-0899 THE ARCH AND COLONNAD E OF THE MANHATTAN BRIDGE APPROACH, Manhattan Bridge Plaza at Canal Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1912-15; architects Carr~re & Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough o£Manhattan Tax Map Block 290, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the described improvement is situated. On September 23, 1975, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Arch and Colonnade of the Manhattan Bridge Approach and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No . 3). The hearing had been duly ad vertised in accordance with . the provisions of law. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Manhattan Bridge Approach, a monumental gateway to the bridge, occupies a gently sloping elliptical plaza bounded by Canal, Forsyth and Bayard Streets and the Bowery. Originally designed to accommodate the flow of traffic, it employed traditional forms of arch and colonnade in a monument al Beaux-Arts style gateway. The triumphal arch was modeled after the 17th-century Porte St. Denis in Paris and the colonnade was inspired by Bernini's monumental colonnade enframing St. Peter's Square in Rome. Carr~re &Hastings, whose designs for monumental civic architecture include the New York Public Library and Grand Army Plaza, in Manhattan, were the architects of the approaches to the Manhattan Bridge and designed both its Brooklyn and Manhattan approaches. The design of the Manhattan Bridge , the the third bridge to cross the East River, aroused a good deal of controversy. -

Research Spotlight

Spring Edition 2019 MORE THAN $1 MILLION IN FUNDING APPROVED FOR EQUINE RESEARCH IN 2019 The board of directors of Grayson-Jockey Club Research Foundation has authorized expenditure of $1,338,858 to fund eight new projects at seven universities, nine continuing projects, and three career development awards to fund veterinary research to benefit all horses. This is the fifth straight year that more than $1 million has been approved. 366 Projects “We thank our generous donors who recognize the value of veterinary research for enhancing equine health and wellness,” said Jamie Haydon, president of the foundation. “From studying a racehorse’s stride to predict injury to testing an intrauterine 44 Universities antibiotic treatment, we are excited to see the results of these studies and how they may help horses of all breeds in the future.” Million 27.5 Oaklawn Park and WinStar Farm will each be donating $50,000 in 2019 to sponsor research projects pertaining to health in racehorses. They are participants in Grayson’s Since 1983 new corporate membership program, whereby organizations can contribute to 2019 projects listed on next page Grayson-funded projects. Those interested in the program should contact the foundation. JOHN C. OXLEY TO RECEIVE THE DINNY PHIPPS AWARD We proudly announce that John C. “Jack” Oxley, a longtime Thoroughbred owner and supporter of Grayson, will be presented with the Dinny Phipps Award at a celebration of The Jockey Club’s 125th anniversary in New York City on Thursday, June 6. Earle Mack, an active participant in Thoroughbred racing and breeding for more than five decades, created the award in 2017 in memory of Phipps to honor an individual or individuals who have demonstrated dedication to equine health. -

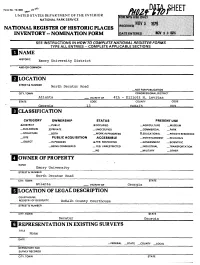

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 , •\0/I tfW UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Emory University District AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER North Decatur Road _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Atlanta VICINITY OF 4th - Elliott H. Levitas STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Georgia ("IRQ CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE JS.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) JSLPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS 2LEDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS .X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Emory University STREET & NUMBER North Decatur Road CITY. TOWN STATE Atlanta VICINITY OF Georgia LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC DeKalb County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Decatur Georgia [1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE KGOOD _RUINS X.ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Emory University, founded in 1915 in Atlanta as an outgrowth of Emory College at Oxford, was designed in plan by Henry Hornbostel, who also designed the original buildings. Although several other architects including the New York library specialist, Edward Tilton and the Atlanta firm of Hentz-Adler-Shulze contributed in later years to the building designs of the Emory Campus, it is the Hornbostel Emory campus plan, dis- criminately set in the Olmsted-influenced Druid Hills area landscape that had and still has a predominating effect on the Emory campus environment. -

History and Organization Table of Contents

History and Organization Table of Contents History and Organization Carnegie Mellon University History Carnegie Mellon Colleges, Branch Campuses, and Institute Carnegie Mellon University in Qatar Carnegie Mellon Silicon Valley Software Engineering Institute Research Centers and Institutes Accreditations by College and Department Carnegie Mellon University History Introduction The story of Carnegie Mellon University is unique and remarkable. After its founding in 1900 as the Carnegie Technical Schools, serving workers and young men and women of the Pittsburgh area, it became the degree-granting Carnegie Institute of Technology in 1912. “Carnegie Tech,” as it was known, merged with the Mellon Institute to become Carnegie Mellon University in 1967. Carnegie Mellon has since soared to national and international leadership in higher education—and it continues to be known for solving real-world problems, interdisciplinary collaboration, and innovation. The story of the university’s famous founder—Andrew Carnegie—is also remarkable. A self-described “working-boy” with an “intense longing” for books, Andrew Carnegie emigrated from Scotland with his family in 1848 and settled in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He became a self-educated entrepreneur, whose Carnegie Steel Company grew to be the world’s largest producer of steel by the end of the nineteenth century. On November 15, 1900, Andrew Carnegie formally announced: “For many years I have nursed the pleasing thought that I might be the fortunate giver of a Technical Institute to our City, fashioned upon the best models, for I know of no institution which Pittsburgh, as an industrial centre, so much needs.” He concluded with the words “My heart is in the work,” which would become the university’s official motto. -

Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine

THE WESTERN PENNSYLVANIA HISTORICAL MAGAZINE Volume 52 April 1969 Number 2 A HERITAGE OF DREAMS Some Aspects of the History of the Architecture and Planning of the University of Pittsburgh, 1787-1969 James D.Van Trump architectural history of any human institution is no incon- siderable part of that organization, whether it is a church or Thelibrary, bank or governmental agency; its building or buildings are its flesh by which in all phases of its development its essential image is presented to the world. Nowadays, as site and area planning come increasingly to the fore, the relation of groups of buildings to the land is receiving more attention from historians. Institutions of higher learning with their campuses and their interaction with larger social, architectural, and planning especially amenable to this patterns are' type of study. 1 An exhibition of the history of the architecture and planning of the University of Pittsburgh from 1787 to 1969 was held recently in Mr. Van Trump who is Vice-President and Director of Research of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation and the editor of Chorette, the Pennsylvania Journal of Architecture, is well-known as an authority on the building history of Western Pennsylvania and as a frequent contributor to this magazine. He is currently working on a book dealing with the architecture of the Allegheny County Court House and Jail and he hopes to publish inbook form his researches into the architectural history of the University of Pitts- burgh.—Editor 1 Such studies are not exactly new as evidenced by the series of articles on American college campuses published in the Architectural Record from 1909-1912 by the well known architectural critic and journalist, Montgomery Schuyler (1843-1914). -

Hubert G. Phipps

Hubert G. Phipps See all social media accounts for Hubert Phipps. Run a full report to access Hubert's email address, phone number, house address and more. We found 11 records for Hubert Phipps in 11 states. We found 3 social media accounts, including a public Facebook profile associated with Hubert Lee Phipps who is 68 years of age and resides in Yukon, OK. Uncover details on Hubert's Social Media Profiles, Public Records, Criminal Records & much more. See more Seen As: Phipps Hubert. Addresses: Po Box 956, Middleburg, VA; 455 Australian Ave # 2b, Palm Beach, FL; 455 Australian Ave, Palm Beach, FL. Previous Locations: West Palm Beach, FL; Miami Beach, FL; Wellington, FL; Miami, FL. View Profile. Hubert A Phipps. City: Westlake, Ohio Age: 92. View Profile. See more of Hubert Phipps on Facebook. Log In. or. Hubert Phipps is at New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture. · 19 July 2017 ·. The âœWhitneyâ New York Studio School of Drawing, Painting and Sculpture. Hubert Phipps. · 18 July 2017 ·. Working on âœSegue.â Hubert Phipps. · 18 July 2017 · Instagram ·. âœSegueâ getting worked on at the @ny_studioschool #metalshop. Hubert Phipps. · 14 July 2017 ·. Sketch for yet to be titled. #sculptureproject. Hubert Phipps. · 13 July 2017 ·. The latest Tweets from Hubert Phipps Studio (@HubertPhipps). Artist || sculptures, paintings, drawings & specialty projects. "I like things that are different. That is what fascinates me about abstract art. New to Twitter? Sign up. Hubert Phipps Studio. @HubertPhipps. Tweets Tweets, current page. -

Charles L. Rosenblum, Ph.D. 3934 California Ave., #2 [email protected] Pittsburgh, PA 15212 412 979 3477

Charles L. Rosenblum, Ph.D. 3934 California Ave., #2 [email protected] Pittsburgh, PA 15212 412 979 3477 Education 2009 Ph.D. in Architectural History, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA Dissertation: The Architecture of Henry Hornbostel Concentrations: American architecture; Modern European, and Renaissance/Baroque 1997 Master of Architectural History, University of Virginia Thesis Topic: "Frank Lloyd Wright's San Francisco Office" 1987 Bachelor of Arts major in art history, Yale University, New Haven, CT Employment (Academic) Fall 2009- Assistant Teaching Professor, School of Architecture, School of Art, Carnegie Mellon University, Spring 2012 Pittsburgh, PA Fall 2000 - Adjunct Assistant Professor, School of Architecture, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA Spring 2009 Fall 2006 - Adjunct Assistant Professor, School of Art, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, PA Spring 2000 Courses at CMU: Critical Histories of the Arts: Spring 2010, 2011, 2012 Modern Visual Culture, Fall 2007-11 Contemporary Visual Culture, Spring 2008 Synergistic Space, Fall 2006 Contemporary Architectural Theory I, Fall 2007, 2008, 2011 Contemporary Architectural Theory II, Spring 2008 History of Sustainable Architecture, Fall 2004, 2010 Spring 2006 Renaissance and Baroque Architecture, Spring 2003-5 “Buzzwords,” Contemporary Architectural Speech, Spring 2002 Architecture of Henry Hornbostel, Fall 2000 – Fall 2003, 2007 Fall 1999 - Adjunct Assistant Professor, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, Indiana, Pennsylvania Spring 2001 Courses at IUP Introduction to Art, Fall 1999 – Spring 2000 Arts of the Twentieth Century, Fall 2000 Modern Art, Spring, Spring 2001 Senior Seminar in Art, Fall 2000 Employment (Professional) 1999 – Architecture Critic, Pittsburgh City Paper. Pittsburgh, PA. Regular column, “Writing on the present Walls,” as well as additional news stories, reviews. -

Silver Spoon Oligarchs

CO-AUTHORS Chuck Collins is director of the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies where he coedits Inequality.org. He is author of the new book The Wealth Hoarders: How Billionaires Pay Millions to Hide Trillions. Joe Fitzgerald is a research associate with the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Helen Flannery is director of research for the IPS Charity Reform Initiative, a project of the IPS Program on Inequality. She is co-author of a number of IPS reports including Gilded Giving 2020. Omar Ocampo is researcher at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good and co-author of a number of reports, including Billionaire Bonanza 2020. Sophia Paslaski is a researcher and communications specialist at the IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good. Kalena Thomhave is a researcher with the Program on Inequality and the Common Good at the Institute for Policy Studies. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank Sarah Gertler for her cover design and graphics. Thanks to the Forbes Wealth Research Team, led by Kerry Dolan, for their foundational wealth research. And thanks to Jason Cluggish for using his programming skills to help us retrieve private foundation tax data from the IRS. THE INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES The Institute for Policy Studies (www.ips-dc.org) is a multi-issue research center that has been conducting path-breaking research on inequality for more than 20 years. The IPS Program on Inequality and the Common Good was founded in 2006 to draw attention to the growing dangers of concentrated wealth and power, and to advocate policies and practices to reverse extreme inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunity. -

Curriculum Vitæ

CURRICULUM VITÆ October 1, 2020 Christopher Drew Armstrong employer University of Pittsburgh (since 2005) positions Associate Professor of History of Art & Architecture (primary appointment) Associate Professor of French & Italian (seconDary appointment) Director of Architectural StuDies (since May 2006) address Department of History of Art anD Architecture 104 Henry Clay Frick Fine Arts BuilDing University of Pittsburgh Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15260 email [email protected] Education Columbia University, Department of Art History & Archaeology: Ph.D. (May 2003) • advisors: Robin Middleton and Barry Bergdoll • Dissertation: Progress in the Age of Navigation. The Voyage Philosophique of Julien-David Leroy University of Toronto, GraDuate Department of History of Art: M.A. (May 1994) University of Toronto, Faculty of Architecture & LanDscape Architecture: B.Arch. (May 1992) Previous University Positions Université De Nantes – Department of History of Art • Visiting Associate Professor (November-December 2015) Massachusetts Institute of Technology – Department of Architecture • Visiting Associate Professor in the History, Theory, Criticism Program (Fall 2012) University of Toronto • Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of Fine Art (2004-05) • Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Architecture, Landscape & Design (2002-03) University Service | University of Pittsburgh • Mascaro Center for Sustainable Innovation – member of TasK Force (since 2013) • Chancellor’s Sustainability Council – member (since 2016) • Dietrich School of -

Guastavino Structural Tile Vaulting in Pittsburgh Spring Semester 2021

The Osher Lifelong Learning Institute University of Pittsburgh, College of General Studies Guastavino Structural Tile Vaulting in Pittsburgh Spring Semester 2021 Instructor: Matthew Schlueb Program Format: Five week course, 90 minute academic lectures and guided tour, with time for questions. Course Objective: To offer a master level survey of the Pittsburgh architectural works by Rafael Guastavino and his son, drawn from their Catalan traditions in masonry vaulting, as interpreted by a practicing architect and author of architecture. Course Description: Architect Rafael Guastavino and his son Rafael Jr. emigrated to the United States in 1881, bringing the traditional construction method of structural tile vaulting from their Catalan homeland, thereby transforming the architectural landscape from Boston to San Francisco. This course will examine their works in Pittsburgh, illustrating the vaults and domes made with structural tiles, innovations in thin shell construction, fire-proofing, metal reinforcing, herringbone patterns, skylighting, acoustical and polychromatic tiles. Lectures supplemented with a guided tour of these local structures, provided logistics and health safety measures permit. Course Outline: Lecture 1: From Valencia to New York [Tuesday, March 16, 2021 3pm-4:30pm] Convent of Santo Domingo Refectory (arches and vaults; Mudéjar style; Zaragoza, Spain; 1283) Monastery of Santo Domingo Refectory (bóveda tabicadas / maó de pla; Juan Franch; Valencia, Spain; 1382) Batlló Textile Factory (vaulted arcade atop metal columns; Rafael Guastavino; Barcelona, Spain; 1868) La Massa Theater (shallow dome vault; Rafael Guastavino; Vilassar de Dalt, Spain; 1880) Boston Public Library (structural tile vaults; Charles McKim; Boston, Massachusetts; 1889-1895) St. Paul’s Chapel (dome; Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes; Columbia University, New York; 1907) Lecture 2: Material Innovations in Building Science [Tuesday, March 23, 2021 3pm-4:30pm] Cathedral of St. -

North Shore Sample

T a b l e o f C o n t e n t s Volume I Acknowledgments . iv Introduction . vii Maps of Long Island Estate Areas . xiv Factors Applicable to Usage . xvii Surname Entries A – M . 1 Volume II Surname Entries N – Z . 803 Appendices: ArcHitects . 1257 Civic Activists . 1299 Estate Names . 1317 Golf Courses on former NortH SHore Estates . 1351 Hereditary Titles . 1353 Landscape ArcHitects . 1355 Maiden Names . 1393 Motion Pictures Filmed at NortH SHore Estates . 1451 Occupations . 1457 ReHabilitative Secondary Uses of Surviving Estate Houses . 1499 Statesmen and Diplomats WHo Resided on Long Island's North Shore . 1505 Village Locations of Estates . 1517 America's First Age of Fortune: A Selected BibliograpHy . 1533 Selected BibliograpHic References to Individual NortH SHore Estate Owners . 1541 BiograpHical Sources Consulted . 1595 Maps Consulted for Estate Locations . 1597 PhotograpHic and Map Credits . 1598 I n t r o d u c t i o n Long Island's NortH SHore Gold Coast, more tHan any otHer section of tHe country, captured tHe imagination of twentieth-century America, even oversHadowing tHe Island's SoutH SHore and East End estate areas, wHich Have remained relatively unknown. THis, in part, is attributable to F. Scott Fitzgerald's The Great Gatsby, whicH continues to fascinate the public in its portrayal of the life-style, as Fitzgerald perceived it, of tHe NortH SHore elite of tHe 1920s.1 The NortH SHore estate era began in tHe latter part of the 1800s, more than forty years after many of the nation's wealtHy Had establisHed tHeir country Homes in tHe Towns of Babylon and Islip, along tHe Great SoutH Bay Ocean on tHe SoutH Shore of Long Island.