Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Oct. 4, 2010, Issue of the Pitt

INSIDE ODK walkway is rededicated.................... 3 Pitt research endeavors.................... 4-5 PittNewspaper of the University of PittsburghChronicle Volume XI • Number 27 • October 4, 2010 Pitt Planet Hunters Track Long, Strange Voyage of Pitt No. 8 Among All Distant Planet as Part of International Collaboration U.S. Public Universities By Morgan Kelly University of Pittsburgh planet In Federally Financed hunters based at the Allegheny Observatory were one of nine teams R&D Expenditures around the world that tracked a planet 190 light-years from Earth making By John Harvith its rare 12-hour passage in front of its star. The project resulted in The University of Pittsburgh is ranked the first ground-based observation No. 8 among all U.S. public universities and of the entire unusually drawn-out 13th among all U.S. universities, public and transit and established a practical private, in federally financed R&D expen- technique for recording the move- ditures for fiscal year 2009, according to ment of other exoplanets, or planets a Sept. 28 Chronicle of Higher Education outside of Earth’s solar system, the listing based upon a National Science Foun- teams reported in The Astrophysical dation report issued on Sept. 27. Journal. The other top-ranked public uni- The Pitt team, led by Melanie versities in the listing are Michigan, the Good, a physics and astronomy University of Washington, UC-San Diego, graduate student in Pitt’s School Wisconsin, Colorado, UC-San Francisco, of Arts and Sciences, observed the and UCLA. The top-ranked private uni- planet HD 80606b for more than 11 versities in the listing are Johns Hopkins, hours on Jan. -

PHLF News Publication

Protecting the Places that Make Pittsburgh Home Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation Nonprofit Org. 1 Station Square, Suite 450 U. S. Postage Pittsburgh, PA 15219-1134 PAID www.phlf.org Pittsburgh, PA Address Service Requested Permit No. 598 PHLF News Published for the members of the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation No. 160 April 2001 Landmarks Launches Rural In this issue: 4 Preservation Program Landmarks Announces Its Gift Annuity Program Farms in Allegheny County—some Lucille C. Tooke Donates vent non-agricultural development. with historic houses, barns, and scenic Any loss in market value incurred by 10 views—are rapidly disappearing. In Historic Farm Landmarks in the resale of the property their place is urban sprawl: malls, Through a charitable could be offset by the eventual proceeds The Lives of Two North Side tract housing, golf courses, and high- remainder unitrust of the CRUT. Landmarks ways. According to information from (CRUT), long-time On December 21, 2000, Landmarks the U. S. Department of Agriculture, member Lucille C. succeeded in buying the 64-acre Hidden only 116 full-time farms remained in Tooke has made it Valley Farm from the CRUT. Mrs. Tooke 12 Allegheny County in 1997. possible for Landmarks is enjoying her retirement in Chambers- Revisiting Thornburg to acquire its first farm burg, PA and her three daughters are property, the 64-acre Hidden Valley excited about having saved the family Farm on Old State Road in Pine homestead. Landmarks is now in the 19 Township. The property includes a process of selling the protected property. Variety is the Spice of Streets house of 1835 that was awarded a “I believe Landmarks was the answer Or, Be Careful of Single-Minded Planning Historic Landmark plaque in 1979. -

The Arch and Colonnade of the Manhattan Bridge Approach and the Proposed Designation of the Related Landmark Site (Item No

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 25, 1975, Number 3 LP-0899 THE ARCH AND COLONNAD E OF THE MANHATTAN BRIDGE APPROACH, Manhattan Bridge Plaza at Canal Street, Borough of Manhattan. Built 1912-15; architects Carr~re & Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough o£Manhattan Tax Map Block 290, Lot 1 in part consisting of the land on which the described improvement is situated. On September 23, 1975, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Arch and Colonnade of the Manhattan Bridge Approach and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No . 3). The hearing had been duly ad vertised in accordance with . the provisions of law. Two witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Manhattan Bridge Approach, a monumental gateway to the bridge, occupies a gently sloping elliptical plaza bounded by Canal, Forsyth and Bayard Streets and the Bowery. Originally designed to accommodate the flow of traffic, it employed traditional forms of arch and colonnade in a monument al Beaux-Arts style gateway. The triumphal arch was modeled after the 17th-century Porte St. Denis in Paris and the colonnade was inspired by Bernini's monumental colonnade enframing St. Peter's Square in Rome. Carr~re &Hastings, whose designs for monumental civic architecture include the New York Public Library and Grand Army Plaza, in Manhattan, were the architects of the approaches to the Manhattan Bridge and designed both its Brooklyn and Manhattan approaches. The design of the Manhattan Bridge , the the third bridge to cross the East River, aroused a good deal of controversy. -

Library Collections and Services

Library Collections and Services The University of Pittsburgh libraries and collections The University of Pittsburgh is a member of the provide an abundant amount of information and services to the Association of Research Libraries. Through membership in University’s students, faculty, staff, and researchers. In fiscal several Pennsylvania consortia of libraries, which include year 2001, the University's 29 libraries and collections have PALCI, PALINET, and the Oakland Library Consortium, surpassed 4.4 million volumes. Additionally, the collections cooperative borrowing arrangements have been developed with include more than 4.3 million pieces of microforms, 32,500 print other Pennsylvania institutions. Locations of University libraries subscriptions, and 5,400 electronic journals. and collections are as follows: The University Library System (ULS) includes the following libraries and collections: Hillman (main), African American, Buhl University Library System (social work), East Asian, Special Collections, Government Documents, Allegheny Observatory, Archives Service Center, Hillman Library ......... Schenley Drive at Forbes Avenue Center for American Music, Chemistry, Computer Science, Hillman Library (main) .................... All floors Darlington Memorial (American history), Engineering (Bevier African American Library ................. First Floor Library), Frick Fine Arts, Information Sciences, Katz Graduate Buhl Library (social work) ................. First Floor School of Business, Langley (biological sciences, East Asian Library -

Campus Map 2006–07 (09-2006) UPSB

A I B I C I D I E I F I G BRA N E . CKENRIDGE BAPS . � T � B X CATHO MELWD ATHLETIC T ELLEF E FIELDS P P SP � Y D R I V R IS T U AUL D CHDEV E S BELLT LKS I T F K E P AR ELD WEBSR E FA ARKM IN N R AW 1 VA E CR 1 R NU E R T E LEVT C A H AV T Y FIFT S RUSK U E G V S MP A O N N E MUSIC SOUTH CRAIG STREE T N B N LA N A UNIVERSIT R N Y U COS P A W O P S E P VE SO I UCT P LO O . S S U L P HENR Y S T T U H E Y N A D L UTD N . Q T C U I L G FR E N T A CRAI S. MELLI L BIG TH B O Y V L C I AT I A N E O BELLEFIELD E CHVR . UE EBER E V HOLD R P MP V A N D I I O P S T . V WINTHR R R IT E M E D D C VE V PANTH N A FRAT I AT ALU H R Y Y U FR T R I T SRC CRGSQ D U S E TH T N I R I Z BELLH V E ID S F S M B P R AW D IG FI HEIN . O L E TH G F I L M O R E S T L N PAHL V EH UN I ET O SOSA E A E IL A N E F I LO R VE L U PA R S 2 A TR T 2 R RSI W A T N T C LRDC VNGR S CATHEDRAL . -

Falll 05 Newsletter

THE FRENCH ROOM In 1936, Chairman Louis Celestin met with officials in the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, resulting in the decision that the French Room should be designed by a French architect in Paris as the gift of the French government. Jacques Carlu was selected to make the final drawings. M. Carlu chose the Empire period, with his inspiration coming from the Napoleonic campaigns and the rediscovery of the art of classical civilizations, with the color scheme of grey, blue and gold. Jacques Carlu had been a member of the faculty at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Upon his return to France, he became director of the School of Architecture at Fontainebleau. To oversee the day-to-day activity, another French architect living in America, Paul Cret, one of the greatest authorities on French architecture at the time, worked with A. A. Klimcheck, University architect, and Gustav Ketterer, Philadelphia decorator, in the construction phase of the room. THE WALLS The wooden walls are painted with a translucent shade of grey known as French gray or grisaille. Luminous with a peculiar transparent quality, it was widely used in famous French interiors during the Empire Period. Slender pilasters are capped with delicately carved crowns, highlighted by gold leaf against a bronze background. Egyptian griffons and classical rosettes combine with Greek acanthus sprigs to accentuate the panel divisions. The paneling is designed to frame the black glass chalkboards. The display case contains a variety of objects d’art. THE FLOOR A highly polished parquet floor is laid in a pattern found in many of the rooms in the palace of Versailles. -

News from Pitt

University of Pittsburgh: News From Pitt Volume 37 Number 12 February 17, 2005 CALENDAR Thursday 17 Medical Grand Rounds “Diabetic Neuropathy,” Bruce Nicholson; west wing aud., Shadyside, 8 am Latin American Studies Social & Public Policy Conference Dining Rm. B WPU, 8:30 am-3:25 pm; keynote address: “Challenges to Democracy in Latin America,” Mitchell Seligson, Vanderbilt; 3:40 pm TIAA-CREF One-on-One Counseling Sessions 100 Craig, 8:30 am-4:30 pm (appointment: 877/209-3136; also Feb. 18, 22, 23 & March 3) Asian Studies Lecture “Viewing Emotively: Memories of Local Dwellings in New Chinese Cinema,” Xinmin Liu, East Asian; 4130 Posvar, noon Immunology Seminar “Toll/IL-1 Receptor Signaling: Trafficking in TRAF-To Raft or Dive, That Is the Question!” Philip Auron, molecular genetics & biochemistry; lecture rm. 5 Scaife, noon (8-7050) OIS Intercultural Lunch Dining Rm. B WPU, noon (4-2100; also Feb. 24 & March 3) PA Black Conference on Higher Education Founders Luncheon Pgh. Hilton Hotel, noon-2 pm (4-3362) Renal Grand Rounds “The EQUAL Study: Assessing Processes & Outcomes for Esrd Quality of Care,” Neil Powe; F1145 Presby, noon Ctr. for Bioethics & Health Law Grand Rounds “White-Washing Health Disparities: Myths, Lies & Misconceptions,” Annette Dula, U of CO; 2nd fl. aud. WPIC, noon (8-1305) PA Black Conference on Higher Education Scholarship Luncheon Pgh. Hilton Hotel, 12:15-2 pm (4-3362) Biostatistics Seminar Debashis Ghosh, U of MI; A115 Crabtree, 3:30 pm Bioengineering/McGowan Inst. Seminar “Challenges in Therapy for Congestive Heart Failure,” Robert Kormos; lecture rm. 6 Scaife, 4 pm http://www.umc.pitt.edu:591/u/FMPro?-DB=ustory&-Format=d.html&-lay=a&storyid=2421&-Find (1 of 8)2/23/2005 5:13:05 PM University of Pittsburgh: News From Pitt Chemistry Lecture “Simple Models for Biological Processes & Material Properties,” Rigoberto Hernandez, GA Inst. -

Theta Tau University of Pittsburgh Petition for Chapter Status

THETA TAU UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH PETITION FOR CHAPTER STATUS PITTSBURGH, PA 3/25/2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH COLONY OF THETA TAU CONTENTS LETTER FROM REGENT 2 MEMBER SIGNATURES 3 EXECUTIVE POSITIONS 4 FOUNDING FATHERS 5 ALPHA CLASS 9 BETA CLASS 13 GAMMA CLASS 16 DELTA RUSH CLASS 18 ALUMNI 19 HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH 20 SWANSON SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING 22 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH THETA TAU 23 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT 24 SERVICE 25 BROTHERHOOD AND SOCIAL ACTIVITIES 27 RECRUITMENT AND PLEDGING 29 LETTERS OF RECOMMENDATION 30 PETITION FOR CHAPTER STATUS Page 1 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH COLONY OF THETA TAU PETITION FOR CHAPTER STATUS Page 2 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH COLONY OF THETA TAU PETITION FOR CHAPTER STATUS Page 3 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH COLONY OF THETA TAU MEMBERS FOUNDING FATHERS 1. Bruk Berhneau Office: Treasurer Hometown: Solon, OH Major: Civil and Environmental Engineering Graduation Date: April 2013 GPA: 3.2 Campus Activities: Epsilon Sigma Alpha, EXCEL, Engineers for a Sustainable World, ASCE E-mail: [email protected] 2. Ross Brodsky Hometown: Marlton, NJ Major: Chemical Engineering; Bioengineering Minor Graduation Date: April 2012 GPA: 3.40 Campus Activities: Little Lab Researcher, Intern at UPitt Office of Technology Management, Chemistry TA, Freshman Peer Advisor & Conference Co-Chair E-mail: [email protected] 3. Erin Dansey Hometown: Parkersburg, West Virginia Major: Mechanical Engineering Graduation Date: December 2012 GPA: 3.0 Campus Activities: Co-op E-mail: [email protected] 4. Tyler Gaskill Hometown: Marlton, NJ Major: Chemical Engineering Graduation Date: December 2012 GPA: 3.70 Campus Activities: Valspar Co-Op, Research E-mail: [email protected] PETITION FOR CHAPTER STATUS Page 4 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH COLONY OF THETA TAU 5. -

Frick Fine Arts Building

University of Pittsburgh Frick Fine Arts Building 650 Schenley Drive Occupant Information This information is for occupants of Alumni Hall. University guidelines for workplace safety, emergency preparedness and emergency response are found in the University of Pittsburgh Safety Manual https://www.ehs.pitt.edu/manual and the University of Pittsburgh Emergency Management Guidelines found on https://www.emergency.pitt.edu/resources/emergency-management-guidelines. In the event of a fire in Frick Fine Arts, the entire building will signal fire alarm conditions. If the fire alarm signal (visual strobe lights and audible horns) activates, evacuate the building. The fire alarm pull stations are located at the exit doors and near the stairwells. 1. If you hear or observe the fire alarm signal: i. Close the door behind you and evacuate the building by following the Exit signs to nearest stairwell or exterior door. Do not use the elevators during an alarm condition, unless directed by an emergency responder. ii. Proceed to an assembly point away from the building. The closest assembly area for Frick Fine Arts is Wesley Posvar Hall at 230 South Bouquet Street. iii. Do not re-enter until the “all clear” signal is given by the police or fire department. 2. Upon discovery of smoke or fire: i. Alert anyone in immediate danger. ii. Close the door to contain smoke or fire. iii. Activate the nearest pull station. iv. Evacuate the building. Note: If you cannot activate the pull station and you are in a safe area, call 911 or call University Police at 412-624-2121. -

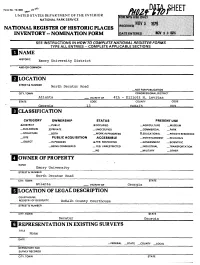

National Register of Historic Places Inventory - Nomination Form

Form No. 10-300 , •\0/I tfW UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Emory University District AND/OR COMMON LOCATION STREET & NUMBER North Decatur Road _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Atlanta VICINITY OF 4th - Elliott H. Levitas STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Georgia ("IRQ CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE JS.DISTRICT —PUBLIC ^OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM _BUILDING(S) JSLPRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS 2LEDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS .X-YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Emory University STREET & NUMBER North Decatur Road CITY. TOWN STATE Atlanta VICINITY OF Georgia LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS.ETC DeKalb County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY. TOWN STATE Decatur Georgia [1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY. TOWN STATE CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X.ORIGINALSITE KGOOD _RUINS X.ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Emory University, founded in 1915 in Atlanta as an outgrowth of Emory College at Oxford, was designed in plan by Henry Hornbostel, who also designed the original buildings. Although several other architects including the New York library specialist, Edward Tilton and the Atlanta firm of Hentz-Adler-Shulze contributed in later years to the building designs of the Emory Campus, it is the Hornbostel Emory campus plan, dis- criminately set in the Olmsted-influenced Druid Hills area landscape that had and still has a predominating effect on the Emory campus environment. -

Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh Records Finding

Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh, Records, 1902-2005 Rauh Jewish Archives Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania MSS #389 62 boxes (boxes 1-62): 31.0 linear feet Foreword - Jewish Community Center of Greater Pittsburgh The Jewish Community Center (JCC) of Greater Pittsburgh evolved from several institutions, each with its own history and each contributing to the establishment of the current JCC. Those institutions will be discussed in separate sections of this history, arranged in alphabetical order. In 1871, Jacob and Isaac Kaufmann, Jewish immigrants from Germany, founded J. Kaufmann & Brother, a merchant-tailoring establishment in the Birmingham section of Pittsburgh. They were soon joined by their younger brothers, Morris and Henry. The success of the business, which eventually became a Kaufmann’s Department Store in downtown Pittsburgh, enabled the Kaufmann families to establish a tradition of civic philanthropy. After World War II, the second generation of the Kaufmann family, Edgar J. and Oliver M. Kaufmann and their brothers-in-laws Irwin D. Wolf and Samuel E. Mundheim continued the family tradition of giving that had been started by the founding brothers. These gifts have contributed to the development of the Jewish community and the city at large. Historical Sketch of the Emma Kaufmann Camp (1908 - ) The Emma Kaufmann Camp (EKC) was founded in 1908 by two Kaufmann brothers, Isaac and Morris, in Harmarville, Pa. The camp was presented as a gift to the community in honor of Morris and Betty Wolf Kaufmann’s 25th wedding anniversary and in memory of Emma Kaufmann, the first wife of Isaac Kaufmann. The Kaufmann families and other donors supported the camp. -

Real Estate Newsletter with Articles (Traditional, 2

Nationality Rooms Newsletter Nationality Rooms and Intercultural Exchange Programs at the University of Pittsburgh http://www.nationalityrooms.pitt.edu/news-events Volume Fall 2017 THE SCOTTISH NATIONALITY ROOM Dedicated July 8, 1938 THE SCOTTISH NATIONALITY ROOM E. Maxine Bruhns The dignity of a great hall bearing tributes to creative men, ancient clans, edu- cation, and the nobility of freedom is felt in the Scottish Nationality Room. The oak doors are adapted from the entrance to Rowallan Castle in Ayrshire. Above the doors and cabinet are lines lauding freedom from The Brus by John Barbour . On either side of the sandstone fireplace are matching kists, or chests. A portrait of Scotland’s immortal poet, Robert Burns, dominates above the mantel. Above the portrait is the cross of St. Andrew, Scotland’s patron saint. Bronze figures representing 13th– and 14th-century patriots William Wallace and Robert the Bruce stand on the mantel near an arrangement of dried heather. The blackboard trim bears a proverb found over a door in 1576: “Gif Ye did as ye should Ye might haif as Ye would.” Names of famous Scots are carved on blackboard panels and above the mantel. Student chairs are patterned after one owned by John Knox. An aumbry, or wall closet, pro- vided the inspiration for the display cabinet. The plaster frieze bears symbols of 14 clans Oak Door whose members served on the Room’s committee. The wrought-iron chandelier design was inspired by an iron coronet retrieved from the battlefield at Bannockburn (1314). Bay win- dows, emblazoned with stained-glass coats of arms, represent the Univer- sities of Glasgow, St.