Evidence of Pilgrimage Bequests in the Wills of the Archdeaconry of Sudbury, 1439-1474

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Council Tax Rates 2020 - 2021

BRECKLAND COUNCIL NOTICE OF SETTING OF COUNCIL TAX Notice is hereby given that on the twenty seventh day of February 2020 Breckland Council, in accordance with Section 30 of the Local Government Finance Act 1992, approved and duly set for the financial year beginning 1st April 2020 and ending on 31st March 2021 the amounts as set out below as the amount of Council Tax for each category of dwelling in the parts of its area listed below. The amounts below for each parish will be the Council Tax payable for the forthcoming year. COUNCIL TAX RATES 2020 - 2021 A B C D E F G H A B C D E F G H NORFOLK COUNTY 944.34 1101.73 1259.12 1416.51 1731.29 2046.07 2360.85 2833.02 KENNINGHALL 1194.35 1393.40 1592.46 1791.52 2189.63 2587.75 2985.86 3583.04 NORFOLK POLICE & LEXHAM 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 175.38 204.61 233.84 263.07 321.53 379.99 438.45 526.14 CRIME COMMISSIONER BRECKLAND 62.52 72.94 83.36 93.78 114.62 135.46 156.30 187.56 LITCHAM 1214.50 1416.91 1619.33 1821.75 2226.58 2631.41 3036.25 3643.49 LONGHAM 1229.13 1433.99 1638.84 1843.70 2253.41 2663.12 3072.83 3687.40 ASHILL 1212.28 1414.33 1616.37 1818.42 2222.51 2626.61 3030.70 3636.84 LOPHAM NORTH 1192.57 1391.33 1590.09 1788.85 2186.37 2583.90 2981.42 3577.70 ATTLEBOROUGH 1284.23 1498.27 1712.31 1926.35 2354.42 2782.50 3210.58 3852.69 LOPHAM SOUTH 1197.11 1396.63 1596.15 1795.67 2194.71 2593.74 2992.78 3591.34 BANHAM 1204.41 1405.14 1605.87 1806.61 2208.08 2609.55 3011.01 3613.22 LYNFORD 1182.24 1379.28 1576.32 1773.36 2167.44 2561.52 2955.60 3546.72 -

Contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (Are Distinguished by Letter Code, Given Below) Those from 1801-13 Have Also Been Transcribed and Have No Code

Norfolk Family History Society Norfolk Marriages 1801-1837 The contents of Volume 14 Norwich Marriages 1813-37 (are distinguished by letter code, given below) those from 1801-13 have also been transcribed and have no code. ASt All Saints Hel St. Helen’s MyM St. Mary in the S&J St. Simon & St. And St. Andrew’s Jam St. James’ Marsh Jude Aug St. Augustine’s Jma St. John McC St. Michael Coslany Ste St. Stephen’s Ben St. Benedict’s Maddermarket McP St. Michael at Plea Swi St. Swithen’s JSe St. John Sepulchre McT St. Michael at Thorn Cle St. Clement’s Erh Earlham St. Mary’s Edm St. Edmund’s JTi St. John Timberhill Pau St. Paul’s Etn Eaton St. Andrew’s Eth St. Etheldreda’s Jul St. Julian’s PHu St. Peter Hungate GCo St. George Colegate Law St. Lawrence’s PMa St. Peter Mancroft Hei Heigham St. GTo St. George Mgt St. Margaret’s PpM St. Peter per Bartholomew Tombland MtO St. Martin at Oak Mountergate Lak Lakenham St. John Gil St. Giles’ MtP St. Martin at Palace PSo St. Peter Southgate the Baptist and All Grg St. Gregory’s MyC St. Mary Coslany Sav St. Saviour’s Saints The 25 Suffolk parishes Ashby Burgh Castle (Nfk 1974) Gisleham Kessingland Mutford Barnby Carlton Colville Gorleston (Nfk 1889) Kirkley Oulton Belton (Nfk 1974) Corton Gunton Knettishall Pakefield Blundeston Cove, North Herringfleet Lound Rushmere Bradwell (Nfk 1974) Fritton (Nfk 1974) Hopton (Nfk 1974) Lowestoft Somerleyton The Norfolk parishes 1 Acle 36 Barton Bendish St Andrew 71 Bodham 106 Burlingham St Edmond 141 Colney 2 Alburgh 37 Barton Bendish St Mary 72 Bodney 107 Burlingham -

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office

Parish Registers and Transcripts in the Norfolk Record Office This list summarises the Norfolk Record Office’s (NRO’s) holdings of parish (Church of England) registers and of transcripts and other copies of them. Parish Registers The NRO holds registers of baptisms, marriages, burials and banns of marriage for most parishes in the Diocese of Norwich (including Suffolk parishes in and near Lowestoft in the deanery of Lothingland) and part of the Diocese of Ely in south-west Norfolk (parishes in the deanery of Fincham and Feltwell). Some Norfolk parish records remain in the churches, especially more recent registers, which may be still in use. In the extreme west of the county, records for parishes in the deanery of Wisbech Lynn Marshland are deposited in the Wisbech and Fenland Museum, whilst Welney parish records are at the Cambridgeshire Record Office. The covering dates of registers in the following list do not conceal any gaps of more than ten years; for the populous urban parishes (such as Great Yarmouth) smaller gaps are indicated. Whenever microfiche or microfilm copies are available they must be used in place of the original registers, some of which are unfit for production. A few parish registers have been digitally photographed and the images are available on computers in the NRO's searchroom. The digital images were produced as a result of partnership projects with other groups and organizations, so we are not able to supply copies of whole registers (either as hard copies or on CD or in any other digital format), although in most cases we have permission to provide printout copies of individual entries. -

NORFOLK. FAR 701 Foulger George (Exors

TRADES DIREC'rORY. J NORFOLK. FAR 701 Foulger George (exors. of), Beding- Gallant James, Moulton St. Michael, Gee Wm. Sunny side & Crow Green ham, Bungay Long Stratton R.S.O farm, Stratton St. Mary, Long Foulger Horace, Snetterton, Thetford Gallant John, Martham, Yarmouth Stra.tton R.S.O Fowell R. Itteringham,Aylsham R.S.O Gallant T. W. Rus.hall, Scole R.S.O Gent Thomas & John, Marsh! Terring Fowell William, Corpusty, Norwich Galley Willia.m, Bintry, Ea. Dereham ton St. Clement, Lynn Fo::r: Charles, Old Hall fann,Methwold, Gamble Henry, Rougbam, Swaffha• Gent George, Marsh, Terrington Si- Stoke Ferry S.O Gamble Hy. Wood Dalling, Norwiclt Clement, Lynn Fo::r: F . .Aslact<>n,Long Stratton R.S.O Gamble Henry Barton, Eau Brink hall, George He.rbert, Rockland All Saints, Fo::r: George, Roughwn, Norwich Wiggenhall St. Mary the Virgia, Attleborough Fox Henry, Brisley, East Dereham Lynn George J. Potter-Heigham, Yarmouth Fo::r: Jas. Great Ellingbam, Attleboro' Gamble Henry Rudd, The Lodge,Wig- Gibbons R. E. West Bradenham,Thtfrd Fox Jn. Swanton Morley, E. Dereham genhall St. Mary the Virgin, Lyna Gibbons John, Wortwell, Harleston Fo::r: Lee, Sidestrand, Oromer Gamble W. Terrington St. Joha, Gibbon& Samuel, Scottow, Norwich Fo::r: R. White ho. Clenchwarton,Lynn Wisbech Gibbons William, Scottow, Norwich Fox Robert, Roughton, Norwich Gamble William, Summer end, East Gibbons W. R. Trunch, N. Walsham Po::r: Samuel, Binham, Wighton R.S.O Walton, Lynn Gibbs & Son, Hickling, Norwich Fo::r: Thomas, Elsing, Ea11t Dereham Gamble Wm. North Runcton, Lyna Gibbs A. G. Guestwick, Ea. Deraham Po::r: W. -

NOTES ABOUT OXBOROUGH, NORFOLK Where the Earliest

NOTES ABOUT OXBOROUGH, NORFOLK Where the earliest known Bassetts of the Bassetts of Norfolk line lived in the 18 th Century . OXBOROUGH, also known as OXBURGH , is a parish and village, 3 miles N.E. of Stoke Ferry and 6½ miles S.W. of Swaffham Norfolk,England. In 1854 it comprised 293 inhabitants, 58 houses, and 2,317 acres of land, all the property of Sir H. R. P. Bedingfield , Bart., of Oxborough Hall. The hall is surrounded by a moat, and is one of the most perfect specimens of ancient castellated mansions in England. It dates from the latter part of the 15th century. The entrance is over a bridge (formerly a draw bridge) through an arched gateway, between two towers 80 feet high. The archway between the towers is supported by groins, and over it is a large room with windows to the north and south. The interior walls were covered with tapestry. Henry VII. is supposed to have satyed there when he visited Oxborough. Oxborough was a place of note in Roman times, and it is considered to be the Iceani of Antoninus, supposed to be at Ickburgh . In 1252 the manor was held by Ralph de Wygarnia, who had a patent for a weekly market on Tuesday, and a yearly fair. The fair was still held for horses and cattle on Easter Tuesday in 1854. Sir Henry Bedingfield of Oxborough Hall was made governor of the Tower of London during the reign of the Catholic Queen, Mary, and had the charge of her sister Elizabeth, who, on ascending the throne, dismissed him from court, saying "whenever she had a state prisoner who required to be hardly handled and strictly kept she would send for him." He was confined to the tower for nearly two years and died in 1655 when his estates were sequestered for his adherence to the cause of Charles I. -

East Ruston, Norfolk, 1851

EAST RUSTON, NORFOLK, 1851 Introduction East Ruston is a village in north-east Norfolk, situated between North Walsham and Stalham. This paper aims to create a portrait of East Ruston in 1851. In the mid-nineteenth century, most of the working population of East Ruston was engaged in agriculture. There were 2,494 acres of land, most of which was arable, but there was also pasture, showing that animals as well as crops were farmed. 1 In 1810, the East Ruston Inclosure Award 2 allotted about 300 acres of land to the Trustees of the Poor, and the poor were able to cut fuel and pasture their cattle on it. 3 In 1851 there were 183 heads of household 4 and 845 inhabitants. The most common occupation by far was agricultural labourer, followed by farmer. Some also worked on the water in such occupations as waterman, boatman and fisherman. In 1825-6 the North Walsham and Dilham Canal was constructed, linked to the River Ant, and a staithe was built at East Ruston, behind Chapel Road, which was used for landing coals etc. 5 There was also a corn mill – East Ruston postmill – which dated from at least the eighteenth century. In the early part of the nineteenth century, it was owned by Rudd Turner, who is best known for killing his wife and baby in 1831. 6 East Ruston towermill, which is depicted on the East Ruston village sign, was built in 1868. 7 Heads of Household The 1851 census shows that all but two of the 183 heads of household were born in Norfolk, 71 of them in East Ruston itself. -

Norfolk Boreas Limited Document Reference: 5.1.12.3 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(Q)

Norfolk Boreas Offshore Wind Farm Consultation Report Appendix 12.3 Scoping area and PCZ mailing area map Applicant: Norfolk Boreas Limited Document Reference: 5.1.12.3 Pursuant to APFP Regulation: 5(2)(q) Date: June 2019 Revision: Version 1 Author: Copper Consultancy Photo: Ormonde Offshore Wind Farm This page is intentionally blank. Norfolk Boreas Offshore Wind Farm Appendices 585000 590000 595000 600000 605000 610000 615000 620000 625000 630000 635000 640000 Thornage Mundesley Indicative Onshore Elements of Brinton Hunworth Thorpe Market theSouth Project Creake (incl. Landfall, CableHoughton Hanworth St Giles Gunthorpe Stody Relay Station Zones, and Project Plumstead Matlaske Thurgarton Trunch F Great Snoring 335000 East Barsham Briningham Edgefield Alby Hill Knapton 335000 Substation Zone) Thursford West Barsham Little Bacton Ramsgate Barningham Wickmere Primary Consultation Zone Briston Antingham Little Swanton Street Suffield Snoring Novers Swafield Historic Scoping SculthorpeArea Barney Calthorpe Parish Boundaries (OS, 2017) Kettlestone Fulmodeston Itteringham Saxthorpe North Walsham Dunton Tattersett Fakenham Corpusty Crostwight 330000 330000 Hindolveston Thurning Hempton Happisburgh Common Oulton Tatterford Little Stibbard Lessingham Ryburgh Wood Norton Honing East Toftrees Great Ryburgh Heydon Bengate Ruston Guestwick Wood Dalling Tuttington Colkirk Westwick Helhoughton Aylsham Ingham Guist Burgh Skeyton Worstead Stalham next Aylsham East Raynham Oxwick Foulsham Dilham Brampton Stalham Green 325000 325000 Marsham Low Street Hickling -

Norfolk Map Books

Scoulton Wicklewood Hingham Wymondham Division Arrangements for Deopham Little Ellingham Attleborough Morley Hingham County District Final Recommendations Spooners Row Yare & Necton Parish Great Ellingham Besthorpe Rocklands Attleborough Attleborough Bunwell Shropham The Brecks West Depwade Carleton Rode Old Buckenham Snetterton Guiltcross Quidenham 00.375 0.75 1.5 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD New Buckenham 100049926 2016 Tibenham Bylaugh Beetley Mileham Division Arrangements for Dereham North & Scarning Swanton Morley Hoe Elsing County District Longham Beeston with Bittering Launditch Final Recommendations Parish Gressenhall North Tuddenham Wendling Dereham Fransham Dereham North & Scarning Dereham South Scarning Mattishall Elmham & Mattishall Necton Yaxham Whinburgh & Westfield Bradenham Yare & Necton Shipdham Garvestone 00.425 0.85 1.7 Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD Holme Hale 100049926 2016 Cranworth Gressenhall Dereham North & Scarning Launditch Division Arrangements for Dereham South County District Final Recommendations Parish Dereham Scarning Dereham South Yaxham Elmham & Mattishall Shipdham Whinburgh & Westfield 00.125 0.25 0.5 Yare & Necton Kilometers Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2016 © Crown copyright and database rights 2016 OSGD 100049926 2016 Sculthorpe Fakenham Erpingham Kettlestone Fulmodeston Hindolveston Thurning Erpingham -

Open Space Parish Schedule 2015 20

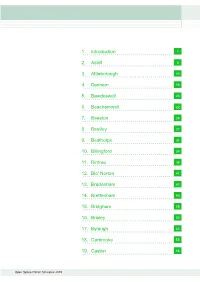

1. Introduction 7 2. Ashill 8 3. Attleborough 10 4. Banham 19 5. Bawdeswell 20 6. Beachamwell 22 7. Beeston 24 8. Beetley 27 9. Besthorpe 32 10. Billingford 34 11. Bintree 38 12. Blo' Norton 41 13. Bradenham 43 14. Brettenham 46 15. Bridgham 48 16. Brisley 50 17. Bylaugh 53 18. Carbrooke 55 19. Caston 58 Open Space Parish Schedule 2015 20. Cockley Cley 60 21. Colkirk 62 22. Cranwich 65 23. Cranworth 67 24. Croxton 70 25. Didlington 72 26. Dereham 73 27. East Tuddenham 88 28. Elsing 90 29. Foulden 92 30. Foxley 94 31. Fransham 96 32. Garboldisham 98 33. Garvestone 101 34. Gateley 104 35. Gooderstone 106 36. Great Cressingham 108 37. Great Dunham 110 38. Great Ellingham 112 Open Space Parish Schedule 2015 39. Gressenhall 114 40. Griston 117 41. Guist 119 42. Hardingham 121 43. Harling 123 44. Hilborough 128 45. Hockering 131 46. Hockham 133 47. Hoe 135 48. Holme Hale 139 49. Horningtoft 143 50. Ickburgh 145 51. Kempstone 147 52. Kenninghall 148 53. Kilverstone 150 54. Lexham 152 55. Litcham 155 56. Little Cressingham 157 57. Little Dunham 159 Open Space Parish Schedule 2015 58. Little Ellingham 161 59. Longham 163 60. Lynford 166 61. Lyng 167 62. Mattishall 169 63. Merton 172 64. Mileham 174 65. Mundford 176 66. Narborough 178 67. Narford 180 68. Necton 182 69. New Buckenham 184 70. Newton 186 71. North Elmham 188 72. North Lopham 190 73. North Pickenham 192 74. North Tuddenham 194 75. Old Buckenham 197 76. Ovington 200 Open Space Parish Schedule 2015 77. -

October 2019).Qxp 2010 Report and Accounts.Qxd 22/10/2019 13:21 Page 821

Bulletin 142 (October 2019).qxp_2010 Report and Accounts.qxd 22/10/2019 13:21 Page 821 Monumental Brass Society OCTOBER 2019 BULLETIN 142 Bulletin 142 (October 2019).qxp_2010 Report and Accounts.qxd 22/10/2019 13:21 Page 822 Monumental Brass Society 822 The Bulletin is published three times a year, in February, June and October. Articles for inclusion Personalia in the next issue should be sent by 1st January 2020 to: It is with very deep regret that we report the death of Jerome Bertram, our senior Vice-President, Martin Stuchfield on Saturday, 19th October 2019 immediately prior Pentlow Hall, Cavendish, Suffolk CO10 7SP to going to press. A full tribute will be published Email: [email protected] in the 2020 Transactions. Contributions to ‘Notes on books, articles and the The Society also deeply regrets the passing of Brian internet’ should be sent by 1st December 2019 to: Kemp and David Parrott who had been members of Richard Busby the Society since 1983 and 1961 respectively. ‘Treetops’, Beech Hill, Hexham Northumberland NE46 3AG Email: [email protected] Useful Society contacts: General enquiries, membership and subscriptions: Penny Williams, Hon. Secretary 12 Henham Court, Mowbrays Road Collier Row, Romford, Essex RM5 3EN Email: [email protected] Conservation of brasses (including thefts etc.): Martin Stuchfield, Hon. Conservation Officer Pentlow Hall, Cavendish, Suffolk CO10 7SP Email: [email protected] Contributions for the Transactions: David Lepine, Hon. Editor 38 Priory Close, Dartford, Kent DA1 2JE Email: [email protected] Website: www.mbs-brasses.co.uk Martin Stuchfield Pentlow Hall, Cavendish, Suffolk CO10 7SP Email: [email protected] The death is also noted of John Masters Lewis Hon. -

The Signpost

The Signpost The Signpost Signpost - Issue 63 Village Contacts Editorial Team: Cockley Cley Editor: Jim Mullenger David Hotchkin [email protected] [email protected] 01760 722 849 Sub Editor & Invoicing: David Stancombe Foulden Next copy date: David Stancombe 14th of March 2021 [email protected] 01366 328 153 Website: fouldennorfolk.org/signpost/ Great Cressingham Hannah Scott For obvious reasons, this is [email protected] a heavily redacted and online 07900 265 493 / 01760 440439 only edition. (At the time of typing, it is possible that No. 64 Gooderstone and Didlington may have to go out in the same Kate Faro-Wood way). So, the saga of Anne [email protected] Murphy and Charles Grantly is 01366 328441 missing (they are on COVID holidays and may return soon). Fiona Gilbert So is any input from our MP [email protected] and Nautical Expressions. I know that the new Hilborough & Bodney lockdown has produced a fair Keith & Linda Thomas amount of gloom and that it SignpostTreasurer doesn’t just apply to me… I’m @btinternet.com (no spaces) hoping that the lengthening of 01760 756 455 days and the onset of Spring will cheer us up. Oxborough On P.7, you will find a link to David Hotchkin (The Editor) some Norfolk walks… I would Email: See above left. very strongly urge you not to 01366 328 442 wander too far from home - and if you get caught, don’t blame Little Cressingham & Threxton me or Signpost! Chris Cannon Ed. [email protected] 2 The Signpost CONTENTS Page Signpost contact details .......................................................... -

Pilgrimage in Medieval East Anglia

Pilgrimage in medieval East Anglia A regional survey of the shrines and pilgrimages of Norfolk and Suffolk Michael Schmoelz Student Number: 3999017 Word Count: 101157 (excluding appendices) Presented to the School of History of the University of East Anglia in partial fulfilment of the requirement for a degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2nd of June 2017 © This thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone wishing to consult it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with the author and that use of any information derived there from must be in accordance with current UK Copyright Law. In addition, any quotation must include full attribution. 1 Contents List of Appendices 6 List of Figures 6 Abstract 11 Methodology 12 Introduction 13 Part One – Case Studies 1. Walsingham 18 1.1. Historiography 18 1.2. Origins: the case against 1061 20 1.3. The Wishing Wells 23 1.4. The rise in popularity, c. 1226-1539 29 1.5. Conclusions 36 2. Bromholm 38 2.1. The arrival of the rood relic: two narratives 39 2.2. Royal patronage 43 2.3. The cellarer’s account 44 2.4. The shrine in the later middle ages: scepticism and satire 48 2.5. Conclusions 52 3. Norwich Cathedral Priory 53 3.1. Herbert Losinga 53 3.2. ‘A poor ragged little lad’: St. William of Norwich 54 3.3. Blood and Bones: other relics at Norwich Cathedral 68 3.4. The sacrist’s rolls 72 3.5. Conclusions 81 2 4. Bury St. Edmunds 83 4.1. Beginnings: Eadmund Rex Anglorum 83 4.2.