The Rhetoric of Structural Reforms: Why Spain Is Not a Good Example of “Successful” European Economic Policies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History of Economic and Monetary Union

Dear Reader, Ahead of the Referendum on the European Union I am compiling a series of fact sheets covering various topics of interest to constituents to allow for a more informed decision when it comes to making your decision to stay in or leave the EU. For further information, visit www.juliegirling.com Julie Girling MEP History of economic and monetary union Economic and monetary union (EMU) is the result of progressive economic integration in the EU. It is an expansion of the EU single market, with common product regulations and free movement of goods, capital, labour and services. A common currency, the euro, has been introduced in the eurozone, which currently comprises 19 EU Member States. All 28 EU Member States — with the exception of the UK and Denmark — must adopt the euro after a minimum of two years’ participation in ERM II and fulfilment of the convergence criteria. A single monetary policy is set by the European Central Bank (ECB) and is complemented by harmonised fiscal and coordinated economic policies. Within EMU there is no single institution responsible for economic policy. Instead, the responsibility is divided between Member States and various EU institutions. Legal basis Decisions of the European Summits of The Hague (1969), Paris (1972), Brussels (1978), Hanover (1988), Madrid and Strasbourg (both 1989), and Maastricht (1991-1992); Articles 119-144, 219 and 282-284 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU); Protocols annexed to the TFEU on: the transition to the third stage of economic and monetary union; the excessive deficit and macroeconomic imbalances procedures; the convergence criteria; the opt-out clauses for the United Kingdom and Denmark; and the European System of Central Banks and the European Central Bank, as well as the Eurogroup Objectives EMU is the result of progressive economic integration, and is therefore not an end in itself. -

The Road to the Euro

One currency for one Europe The road to the euro Ecomomic and Financial Aff airs One currency for one Europe The road to the euro One currency for one Europe The road to the euro CONTENTS: What is economic and monetary union? ....................................................................... 1 The path to economic and monetary union: 1957 to 1999 ............... 2 The euro is launched: 1999 to 2002 ........................................................................................ 8 Managing economic and monetary union .................................................................. 9 Looking forward to euro area enlargement ............................................................ 11 Achievements so far ................................................................................................................................... 13 The euro in numbers ................................................................................................................................ 17 The euro in pictures .................................................................................................................................... 18 Glossary ........................................................................................................................................................................ 20 2 Idreamstock © One currency for one Europe The road to the euro What is economic and monetary union? Generally, economic and monetary union (EMU) is part of the process of economic integration. Independent -

Information Guide Economic and Monetary Union

Information Guide Economic and Monetary Union A guide to the European Union’s Economic and Monetary Union (EMU), with hyperlinks to sources of information within European Sources Online and on external websites Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................... 2 Background .......................................................................................................... 2 Legal basis ........................................................................................................... 2 Historical development of EMU ................................................................................ 4 EMU - Stage One ................................................................................................... 6 EMU - Stage Two ................................................................................................... 6 EMU - Stage Three: The euro .................................................................................. 6 Enlargement and future prospects ........................................................................... 9 Practical preparations ............................................................................................11 Global economic crisis ...........................................................................................12 Information sources in the ESO database ................................................................19 Further information sources on the internet .............................................................19 -

History of Economic and Monetary Union

HISTORY OF ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION Economic and monetary union (EMU) is the result of progressive economic integration in the EU. It is an expansion of the EU single market, with common product regulations and free movement of goods, capital, labour and services. A common currency, the euro, has been introduced in the euro area, which currently comprises 19 EU Member States. All EU Member States – with the exception of Denmark – must adopt the euro once they fulfil the convergence criteria. A single monetary policy is set by the Eurosystem (comprising the European Central Bank’s Executive Board and the governors of the central banks of the euro area) and is complemented by fiscal rules and various degrees of economic policy coordination. Within EMU there is no central economic government. Instead, responsibility is divided between Member States and various EU institutions. LEGAL BASIS — Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU); Articles 3, 5, 119-144, 219 and 282-284 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU); — Protocols annexed to the Treaties: Protocol 4 on the statute of the European System of Central Banks and the European Central Bank; Protocol 12 on the excessive deficit procedure; Protocol 13 on the convergence criteria; Protocol 14 on the Eurogroup; Protocol 16, which contains the opt-out clause for Denmark; — Intergovernmental treaties comprise the Treaty on Stability, Coordination and Governance (TSCG), the Europlus Pact and the Treaty on the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). OBJECTIVES EMU is the result of step-by-step economic integration, and is therefore not an end in itself. -

Innovation Ecosystems in the EU: Banking Sector Case Study1

Innovation Ecosystems in the EU: Banking sector case study1 Ecosistemas de Innovación en la UE: el caso del sector de la Banca Renata KUBUS Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED, España) [email protected] Recepción: Abril 2018 Aceptación: Noviembre 2018 ABSTRACT Traditionally, it has been considered that the banking sector is quite conservative, from the innovative point of view, despite being part of the infrastructure of economic activity. However, especially due to the recent economy/banking sector crisis, digitalization and social and climate changes, there are several attempts in the search of innovation. Following the previously established framework for structural maturity study of the innovation ecosystems, the banking sector is studied from the perspectives of the EU architecture, economic agents, i.e. banks, scholars’ views and society, natural environment impacts. The emerging, overall picture is quite fragmented, there are several issues like the complexity of the banking sector functioning and the structural change subject little attractiveness to the general public. A conscious and orchestrated effort on all the dimensions is required in order to overcome the sub-optimal lock-ins. Key words: Innovation, innovation ecosystems, innovation helix, banking sector, banking innovation. JEL Classification: A13, B59, E42, E50, G20. 1 This document is a part of the Innovation Ecosystems in the EU, PhD thesis Revista Universitaria Europea Nº 30. Enero-Junio 2019: 23-54 ISSN: 1139 -5796 Kubus, R. RESUMEN Tradicionalmente, se ha considerado que el sector bancario es bastante conservador, desde el punto de vista innovador, a pesar de formar parte de la infraestructura de la actividad económica. Sin embargo, y debido a la reciente crisis económica/bancaria, la digitalización y los cambios sociales y climáticos, se observan varios intentos de búsquedas de la innovación. -

A Collection of Financial Keywords and Phrases

A Collection of Financial Keywords and Phrases Abbreviations: CCCN: Customs Cooperation Council Nomenclature CPI: Consumer price index EC: European Communities ECU: European Currency Unit EEC: European Economic Community EU: European Union LDC: Least Developed Country FDI: Foreign Direct Investment FIR: Factor intensity reversal FTA: Free trade area GATT: General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade GDP: Gross domestic product GMO: Genetically modified organism ICA: International commodity agreement ITA: International Trade Administration ITC: International Trade Commission NAFTA: North American Free Trade Agreement NGO: Non-governmental organization NIC: Newly Industrializing Country NTB: Nontariff barrier MNC: Multinational Corporation MNE: Multinational Enterprise OECD: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development SDR: Special Drawing Right TRIP: Trade-Related Intellectual Property Rights UNCTAD: United Nations Conference on Trade and Development VER: Voluntary export restraint WTO: World Trade Organization Abandonment value: The value of a project if the project's assets were sold externally; or alternatively, its opportunity value if the assets were employed elsewhere in the firm. ABC method of inventory control: Method that controls expensive inventory items more closely than less expensive items. Absolute advantage: The ability to produce a good at lower cost, in terms of labor, than another country. An absolute advantage exists when a nation or other economic region is able to produce a good or service more efficiently than a second nation or region. Absolute-priority rule: The rule in bankruptcy or reorganization that claims of a set of claim holders must be paid, or settled, in full before the next, junior, set of claim holders may be paid anything. Absorption and balance of trade: Total demand for goods and services by all residents (consumers, producers, and government) of a country (as opposed to total demand for that country's output). -

Europe Restructured: Vote to Leave

i Europe Restructured: Vote to Leave David Owen Revised 2016 edition Methuen ii First published in Great Britain in 2012 by Methuen & Co 35 Hospital Fields Road York YO10 4DZ Revised editions 2015, 2016 Copyright © David Owen 2012, 2015, 2016 Map in Chapter 1 © Jennifer Owens Cover design: BRILL David Owen has asserted his rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patent Act 1998 to be identified as the author of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-0-413-77798-0 (ebook) This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. iii Contents About the author v Key dates in the history of European integration vi EU terminology xv Europe 2016 xxiv Preface xxv 1. The case for leaving the EU 1 2. The path to the 1975 referendum on the EEC 21 3. The path to the disastrous Eurozone 50 4. Why the Common Foreign and Security Policy is not vital for the UK 77 5. NATO should be the only defence organisation in Europe 98 6. NHS in England: EU law now at the stage where it will prevail 123 7. European Monetary Union 141 iv About the author David Owen was in the House of Commons for 26 years and was Foreign Secretary in James Callaghan’s government from 1977–79. -

European Monetary Union

European Monetary Union his century, which saw two world wars devastate the nations of Europe, will likely conclude with the willing surrender of an Timportant national prerogative in the name of European unity. On January 1, 1999, eleven nations in Europe plan to begin a process of replacing their national currencies with the Euro. This event is at once both unprecedented and part of a development in Europe that stretches back over a quarter of a century. The adoption of the Euro is unprece- dented; never before have so many countries surrendered their national monies for a common currency at a single stroke. In this way, the launching of the Euro means that European countries will be entering uncharted waters. But we have some landmarks that can guide our understanding of the likely consequences of the adoption of the Euro, since European Monetary Union (EMU) is the latest stage in a historical process that began in the wake of the collapse of the Bretton Woods Michael W. Klein system in the early 1970s. As shown in the box “Movement toward a Common European Currency,” European monetary union has pro- gressed in fits and starts since that time. Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, and Associate Professor of International Economics, Fletcher Europe in the Bretton Woods System School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University. This discussion is based The initial moves toward European monetary union began during on a presentation to the Bank’s Board the final days of the Bretton Woods exchange rate system in the early of Directors on January 8, 1998. -

Political Dynamics of the Eurozone Reforms

MAY 2019 A Second-Class Funeral: Political Dynamics of the Eurozone Reforms BRITTA PETERSEN A Second-Class Funeral: Political Dynamics of the Eurozone Reforms BRITTA PETERSEN ABOUT THE AUTHOR Britta Petersen is a Senior Fellow at Observer Research Foundation, where she does research on India-Europe relations. She is a former editor and South Asia Correspondent of the Financial Times Deutschland (FTD) and previously worked as Country Director, Pakistan for the Heinrich Boell Foundation, a think tank affiliated with the German Green Party. ISBN: 978-93-89094-21-3 © 2019 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from ORF. A Second-Class Funeral: Political Dynamics of the Eurozone Reforms ABSTRACT The European Union (EU) stands at a critical junction in its institutional evolution. The European sovereign debt crisis in 2009, the Brexit decision in 2016, and the success of anti-European populist parties in many member states have triggered intense discussions about necessary reforms in the Union, which only intensified after Emmanuel Macron became president of France in 2017. His vehemently pro-European outlook and ambitious suggestions for the governance of the Euro area raised hopes for a reform that would tackle many of the structural flaws of the common currency – probably the most fundamental area of concern in Europe. The continent, however, remains deeply divided over the question of how to govern the Eurozone. This paper tracks the political dynamics of the failed Eurozone reform and argues that the main stumbling stones are the unfinished work of the European integration process. -

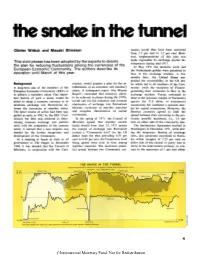

The Snake in the Tunnel

the snake in the tunnel Giinter Wittich and Masaki Shiratori rencies would thus have been narrowed from 1.5 per cent to 1.2 per cent. Ho- ever, implementation of this plan was made impossible by exchange market de- This vivid phrase has been adopted by the experts to denote velopments during mid-1971. the plan for reducing fluctuations among the currencies of the In May 1971 the deutsche mark and European Economic Community. The authors describe its the Netherlands guilder were permitted to operation until March of this year. float in the exchange markets. A few months later, the United States sus- pended the convertibility of the US dol- Background mission, would prepare a plan for the es- lar which led to all members of the Com- A long-term aim of the members of the tablishment of an economic and monetary munity (with the exception of France) European Economic Community (EEC) is union. A subsequent report (the Werner permitting their currencies to float in the to achieve a monetary union. One impor- Report) concluded that monetary union, exchange markets. France continued to tant feature of such a union would be to be achieved in phases during the 1970s, observe the previous margin of fluctuation either to adopt a common currency or to would call for the reduction and eventual against the U S dollar in commercial eliminate exchange rate fluctuations be- elimination of exchange rate fluctuations transactions but instituted a separate mar- tween the currencies of member states. between currencies of member countries ket for capital transactions. Moreover, the The latter course of action had been sug- and complete liberalization of capital Benelux countries agreed to limit the gested as early as 1962 by the EEC Com- movements. -

4. 695 Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal

Research Paper IJMSRR Impact Factor: 4. 695 E- ISSN - 2349-6746 Peer Reviewed & Indexed Journal ISSN -2349-6738 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY SYSTEM: THE CHOICE OF EXCHANGE RATE REGIME Dr. Bigyan P Verma Director, GNIMS Business School. Abstract International monetary systems comprises sets of agreed rules by nations, conventions and supporting institutions, that facilitate global trade, cross border investments and relocation of capital between countries. It provide means of payment acceptable buyers and sellers of different nationality, including deferred payment. To operate successfully, they need to inspire confidence, to provide sufficient liquidity for fluctuating levels of trade and to provide means by which global imbalances can be corrected. The systems can grow organically as the collective result of numerous individual agreements between international economic factors spread over several decades. Alternatively, they can arise from a single architectural vision as happened at Bretton Woods in 1944. This paper traces the history of International Monetary System and establishes its relevance or irrelevance in a world getting increasingly dominated by digitization and its outcome in the shape of Bitcoins, Crypto currencies, Bloackchain, Crowd funding and many other new products where no control can be excersied for all practical purpose. Keywords: International Monetary System, Convertibility, Bretton Woods, Hybrid Exchange Rate System, Brexit, Eu. Introduction International financial markets are characterized by high risk and complex variables. These factors make the gamut of international finance highly volatile and limit the steady growth of trade across nations. In order to lessen the uncertainties and make the world more suitable for the global trade, International Monetary System (IMS) evolved over a period of years. -

Exchange Rate Policy Appropriateness in a Less Developed Country: the Nigerian Case

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 6, June, 2020, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2020 HRMARS Exchange Rate Policy Appropriateness in a Less Developed Country: The Nigerian Case Erhi Moses Akpesiri, Ejechi Jones Oghenemega To Link this Article: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i6/7934 DOI:10.6007/IJARBSS/v10-i6/7934 Received: 09 April 2020, Revised: 12 May 2020, Accepted: 09 June 2020 Published Online: 27 June 2020 In-Text Citation: (Akpesiri, & Oghenemega, 2020) To Cite this Article: Akpesiri, E. M., & Oghenemega, E. J. (2020). Exchange Rate Policy Appropriateness in a Less Developed Country: The Nigerian Case. International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences. 10(6), 1061-1074. Copyright: © 2020 The Author(s) Published by Human Resource Management Academic Research Society (www.hrmars.com) This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this license may be seen at: http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode Vol. 10, No. 6, 2020, Pg. 1061 - 1074 http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/IJARBSS JOURNAL HOMEPAGE Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://hrmars.com/index.php/pages/detail/publication-ethics 1061 International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Vol. 10, No. 6, June, 2020, E-ISSN: 2222-6990 © 2020 HRMARS Exchange Rate Policy Appropriateness in a Less Developed Country: The Nigerian Case Erhi Moses Akpesiri PhD Benson Idahosa University, Benin City Edo State Email: [email protected] Ejechi Jones Oghenemega PhD University of Benin, Benin City Edo State Email: [email protected] Abstract This paper investigated the appropriateness of the exchange rate regime in Nigeria.