A New Interpretation of Certain Bobbin Lace Patterns in Le Pompe, 1559

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palmetto Tatters Guild Glossary of Tatting Terms (Not All Inclusive!)

Palmetto Tatters Guild Glossary of Tatting Terms (not all inclusive!) Tat Days Written * or or To denote repeating lines of a pattern. Example: Rep directions or # or § from * 7 times & ( ) Eg. R: 5 + 5 – 5 – 5 (last P of prev R). Modern B Bead (Also see other bead notation below) notation BTS Bare Thread Space B or +B Put bead on picot before joining BBB B or BBB|B Three beads on knotting thread, and one bead on core thread Ch Chain ^ Construction picot or very small picot CTM Continuous Thread Method D Dimple: i.e. 1st Half Double Stitch X4, 2nd Half Double Stitch X4 dds or { } daisy double stitch DNRW DO NOT Reverse Work DS Double Stitch DP Down Picot: 2 of 1st HS, P, 2 of 2nd HS DPB Down Picot with a Bead: 2 of 1st HS, B, 2 of 2nd HS HMSR Half Moon Split Ring: Fold the second half of the Split Ring inward before closing so that the second side and first side arch in the same direction HR Half Ring: A ring which is only partially closed, so it looks like half of a ring 1st HS First Half of Double Stitch 2nd HS Second Half of Double Stitch JK Josephine Knot (Ring made of only the 1st Half of Double Stitch OR only the 2nd Half of Double Stitch) LJ or Sh+ or SLJ Lock Join or Shuttle join or Shuttle Lock Join LPPCh Last Picot of Previous Chain LPPR Last Picot of Previous Ring LS Lock Stitch: First Half of DS is NOT flipped, Second Half is flipped, as usual LCh Make a series of Lock Stitches to form a Lock Chain MP or FP Mock Picot or False Picot MR Maltese Ring Pearl Ch Chain made with pearl tatting technique (picots on both sides of the chain, made using three threads) P or - Picot Page 1 of 4 PLJ or ‘PULLED LOOP’ join or ‘PULLED LOCK’ join since it is actually a lock join made after placing thread under a finished ring and pulling this thread through a picot. -

NEEDLE LACES Battenberg, Point & Reticella Including Princess Lace 3Rd Edition

NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INCLUDING PRINCESS LACE 3RD EDITION EDITED BY JULES & KAETHE KLIOT LACIS PUBLICATIONS BERKELEY, CA 94703 PREFACE The great and increasing interest felt throughout the country in the subject of LACE MAKING has led to the preparation of the present work. The Editor has drawn freely from all sources of information, and has availed himself of the suggestions of the best lace-makers. The object of this little volume is to afford plain, practical directions by means of which any lady may become possessed of beautiful specimens of Modern Lace Work by a very slight expenditure of time and patience. The moderate cost of materials and the beauty and value of the articles produced are destined to confer on lace making a lasting popularity. from “MANUAL FOR LACE MAKING” 1878 NEEDLE LACES BATTENBERG, POINT & RETICELLA INLUDING PRINCESS LACE True Battenberg lace can be distinguished from the later laces CONTENTS by the buttonholed bars, also called Raleigh bars. The other contemporary forms of tape lace use the Sorrento or twisted thread bar as the connecting element. Renaissance Lace is INTRODUCTION 3 the most common name used to refer to tape lace using these BATTENBERG AND POINT LACE 6 simpler stitches. Stitches 7 Designs 38 The earliest product of machine made lace was tulle or the PRINCESS LACE 44 RETICELLA LACE 46 net which was incorporated in both the appliqued hand BATTENBERG LACE PATTERNS 54 made laces and later the elaborate Leavers laces. It would not be long before the narrow tapes, in fancier versions, would be combined with this tulle to create a popular form INTRODUCTION of tape lace, Princess Lace, which became and remains the present incarnation of Belgian Lace, combining machine This book is a republication of portions of several manuals made tapes and motifs, hand applied to machine made tulle printed between 1878 and 1938 dealing with varieties of and embellished with net embroidery. -

Bobbin Lace You Need a Pattern Known As a Pricking

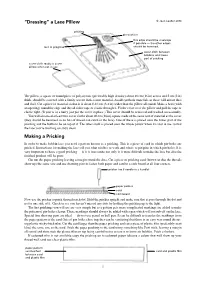

“Dressing” a Lace Pillow © Jean Leader 2014 pricking pin-cushion this edge should be a selvage if possible — the other edges lace in progress should be hemmed. cover cloth between bobbins and lower part of pricking cover cloth ready to cover pillow when not in use The pillow, a square or round piece of polystyrene (preferably high density) about 40 cm (16 in) across and 5 cm (2 in) thick, should be covered with a firmly woven dark cotton material. Avoid synthetic materials as these will attract dust and fluff. Cut a piece of material so that it is about 8-10 cm (3-4 in) wider than the pillow all round. Make a hem (with an opening) round the edge and thread either tape or elastic through it. Fit the cover over the pillow and pull the tape or elastic tight. (If you’re in a hurry just pin the cover in place.) This cover should be removed and washed occasionally. You will also need at least two cover cloths about 40 cm (16 in) square made of the same sort of material as the cover (they should be hemmed so no bits of thread can catch in the lace). One of these is placed over the lower part of the pricking and the bobbins lie on top of it. The other cloth is placed over the whole pillow when it is not in use so that the lace you’re working on stays clean. Making a Pricking In order to make bobbin lace you need a pattern known as a pricking. -

Bobbinwork Basics by Jill Danklefsen

SPECIAL CLASSROOM EDITION BOBBINWORK BASICS BY JILL DANKLEFSEN obbinwork is a technique that places heavy decorative 4. The type of stitch chosen as well as the type of “bobbin yarn” Bthreads on the surface of the fabric, sewn as machine-fed selected will dictate how loose the tension needs to be adjusted decorative stitches or as freemotion stitches. Typically, these on the bobbin case. threads, yarns, and cords are too large to fit through the eye of the sewing machine needle. So, in order to achieve a “stitched 5. Remember the rule of tension adjustment --“Righty, Tighty -- look”, you sew with the heavy decorative thread wound onto a Lefty, Loosey” bobbin and placed in the bobbin case of the machine. 6. Use a “construction quality” thread on the “topside” of your machine, as the needle tension will usually be increased. Think of the top thread as literally pulling the “bobbin yarn” into place to form the stitch pattern. 7. Bobbins can be wound by hand or by machine. Whenever possible, wind the bobbin using the bobbin winder mechanism on the machine. This will properly tension the “bobbin yarn” for a better stitch quality. 8. Bobbinwork can be sewn with the Feed dogs up or down. If stitching freemotion, a layer of additional stabilizer or the use of a machine embroidery hoop may be necessary. 9. Select the proper presser foot for the particular bobbinwork YARNS AND THREADS SUITABLE FOR BOBBINWORK technique being sewn. When working with the heavier “bobbin yarns”, the stitches produced will be thicker. Consider selecting • Yarns (thinner types, often a foot with a large indentation underneath it, such as Foot used for knitting machines) #20/#20C.This foot will ride over the stitching much better. -

Catalogue of the Famous Blackborne Museum Collection of Laces

'hladchorvS' The Famous Blackbome Collection The American Art Galleries Madison Square South New York j J ( o # I -legislation. BLACKB ORNE LA CE SALE. Metropolitan Museum Anxious to Acquire Rare Collection. ' The sale of laces by order of Vitail Benguiat at the American Art Galleries began j-esterday afternoon with low prices ranging from .$2 up. The sale will be continued to-day and to-morrow, when the famous Blackborne collection mil be sold, the entire 600 odd pieces In one lot. This collection, which was be- gun by the father of Arthur Blackborne In IS-W and ^ contmued by the son, shows the course of lace making for over 4(Xi ye^rs. It is valued at from .?40,fX)0 to $oO,0()0. It is a museum collection, and the Metropolitan Art Museum of this city would like to acciuire it, but hasnt the funds available. ' " With the addition of these laces the Metropolitan would probably have the finest collection of laces in the world," said the museum's lace authority, who has been studying the Blackborne laces since the collection opened, yesterday. " and there would be enough of much of it for the Washington and" Boston Mu- seums as well as our own. We have now a collection of lace that is probablv pqual to that of any in the world, "though other museums have better examples of some pieces than we have." Yesterday's sale brought SI. .350. ' ""• « mmov ON FREE VIEW AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK FROM SATURDAY, DECEMBER FIFTH UNTIL THE DATE OF SALE, INCLUSIVE THE FAMOUS ARTHUR BLACKBORNE COLLECTION TO BE SOLD ON THURSDAY, FRIDAY AND SATURDAY AFTERNOONS December 10th, 11th and 12th BEGINNING EACH AFTERNOON AT 2.30 o'CLOCK CATALOGUE OF THE FAMOUS BLACKBORNE Museum Collection of Laces BEAUTIFUL OLD TEXTILES HISTORICAL COSTUMES ANTIQUE JEWELRY AND FANS EXTRAORDINARY REGAL LACES RICH EMBROIDERIES ECCLESIASTICAL VESTMENTS AND OTHER INTERESTING OBJECTS OWNED BY AND TO BE SOLD BY ORDER OF MR. -

Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of Terms Used in the Documentation – Blue Files and Collection Notebooks

Book Appendix Glossary 12-02 Powerhouse Museum Lace Collection: Glossary of terms used in the documentation – Blue files and collection notebooks. Rosemary Shepherd: 1983 to 2003 The following references were used in the documentation. For needle laces: Therese de Dillmont, The Complete Encyclopaedia of Needlework, Running Press reprint, Philadelphia, 1971 For bobbin laces: Bridget M Cook and Geraldine Stott, The Book of Bobbin Lace Stitches, A H & A W Reed, Sydney, 1980 The principal historical reference: Santina Levey, Lace a History, Victoria and Albert Museum and W H Maney, Leeds, 1983 In compiling the glossary reference was also made to Alexandra Stillwell’s Illustrated dictionary of lacemaking, Cassell, London 1996 General lace and lacemaking terms A border, flounce or edging is a length of lace with one shaped edge (headside) and one straight edge (footside). The headside shaping may be as insignificant as a straight or undulating line of picots, or as pronounced as deep ‘van Dyke’ scallops. ‘Border’ is used for laces to 100mm and ‘flounce’ for laces wider than 100 mm and these are the terms used in the documentation of the Powerhouse collection. The term ‘lace edging’ is often used elsewhere instead of border, for very narrow laces. An insertion is usually a length of lace with two straight edges (footsides) which are stitched directly onto the mounting fabric, the fabric then being cut away behind the lace. Ocasionally lace insertions are shaped (for example, square or triangular motifs for use on household linen) in which case they are entirely enclosed by a footside. See also ‘panel’ and ‘engrelure’ A lace panel is usually has finished edges, enclosing a specially designed motif. -

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Identification

Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace DATS in partnership with the V&A DATS DRESS AND TEXTILE SPECIALISTS 1 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Text copyright © Jeremy Farrell, 2007 Image copyrights as specified in each section. This information pack has been produced to accompany a one-day workshop of the same name held at The Museum of Costume and Textiles, Nottingham on 21st February 2008. The workshop is one of three produced in collaboration between DATS and the V&A, funded by the Renaissance Subject Specialist Network Implementation Grant Programme, administered by the MLA. The purpose of the workshops is to enable participants to improve the documentation and interpretation of collections and make them accessible to the widest audiences. Participants will have the chance to study objects at first hand to help increase their confidence in identifying textile materials and techniques. This information pack is intended as a means of sharing the knowledge communicated in the workshops with colleagues and the public. Other workshops / information packs in the series: Identifying Textile Types and Weaves 1750 -1950 Identifying Printed Textiles in Dress 1740-1890 Front cover image: Detail of a triangular shawl of white cotton Pusher lace made by William Vickers of Nottingham, 1870. The Pusher machine cannot put in the outline which has to be put in by hand or by embroidering machine. The outline here was put in by hand by a woman in Youlgreave, Derbyshire. (NCM 1912-13 © Nottingham City Museums) 2 Identifying Handmade and Machine Lace Contents Page 1. List of illustrations 1 2. Introduction 3 3. The main types of hand and machine lace 5 4. -

Needle Arts 3 11628.Qxd

NEEDLE ARTS 3 PACK 11628 • 20 DESIGNS NX670 Flowered Hat Pins NX671 Handmade With Love By NX672 Sewing Bobbin Machine NX673 Rotary Cutter 2.11 X 3.89 in. 3.10 X 2.80 in. 2.49 X 2.50 in. 3.89 X 1.74 in. 53.59 X 98.81 mm 78.74 X 71.12 mm 63.25 X 63.50 mm 98.81 X 44.20 mm 4,587 St. 11,536 St. 10,818 St. 10,690 St. NX674 Dressmaker’s Shears NX675 Thread NX676 Sewing Border NX677 Tracing Wheel 3.89 X 1.88 in. 2.88 X 3.89 in. 5.00 X 2.19 in. 3.46 X 1.74 in. 98.81 X 47.75 mm 73.15 X 98.81 mm 127.00 X 55.63 mm 87.88 X 44.20 mm 7,892 St. 15,420 St. 16,465 St. 3,282 St. NX678 Sewing Angel NX679 Tomato Pincushion NX680 Measuring Tape NX681 Sewing Kit 3.76 X 3.21 in. 3.59 X 3.76 in. 3.69 X 1.78 in. 3.89 X 3.67 in. 95.50 X 81.53 mm 91.19 X 95.50 mm 93.73 X 45.21 mm 98.81 X 93.22 mm 20,593 St. 16,556 St. 8,410 St. 22,777 St. NX682 Iron & Ironing Board NX683 Sewing Machine Needle NX684 Needle Thread NX685 Embroidery Scissors 3.79 X 1.40 in. 1.57 X 2.89 in. 1.57 X 3.10 in. 3.00 X 2.58 in. -

ONE-STEP BOBBIN REPLACEMENT FEATURES QUICK-SET TOP BOBBIN the Easy-To-View Window Tells You at a Glance When More Thread Is Need

ONE-STEP BOBBIN REPLACEMENT FEATURES QUICK-SET TOP BOBBIN The easy-to-view window tells you at a glance when more thread is needed in your bobbin. Simply drop in a full bobbin and the Quickset feature has you ready to sew immediately. F.A.S.T. BOBBIN WINDING SYSTEM Brother's use of the latest technology has made their sewing machines even easier to use. To wind the bobbin, just wind the thread around the bobbin a few times, pass it through the slit in the bobbin winder seat and press the START/STOP button. No need to cut off the excess thread or stop the sewing machine when the bobbin is full. START/STOPBUTTON The gentle sewing start lets you use the machine with confidence with or without the electronic foot control. EASY-TO-USE SPEED ADJUSTMENT The speed adjustment lever lets you smoothly adjust the operation speed from low speed and high speed. Enjoy the freedom of being able to adjust the sewing speed while you sew! F.A.S.T. NEEDLE-THREADING SYSTEM Fast and simple threading says it all! Saves time and your eyesight, by automatically feeding the thread through the needle's eye. STITCH LENGTH / WIDTH ADJUSTMENT Adjustments for stitch length; stitch width and variable needle position make sewing fine details fast and easy. Quilters will love the variable needle position for adjusting the seam allowance. 1-STEP AUTOMATIC BUTTONHOLER 1-Step "Auto-size" buttonholer creates a perfectly uniform buttonhole every time. Simply dial the stitch and follow the directions to sew all four sides of the buttonhole without moving a lever. -

Tips for Minimizing Embroidery Interruptions

TECHNICAL BULLETIN TIPS FOR MINIMIZING EMBROIDERY INTERRUPTIONS Sewing interruptions can be caused by many factors, however the most common causes include the following: • Needle Thread Breakage or Pull-out – not picking up at the beginning of a stitch pattern • Bobbin Thread Run-out or Thread Pick-Up – not picking up at the beginning of a stitch pattern • Improper Thread Trimming • Thread break detector stoppage In order to minimize interruptions during the stitching of complex embroidery patterns, the following vital elements must work together during the embroidery process. These vital elements include: • Proper Digitizing for the fabric and pattern being sewn • Proper Embroidery Machine Maintenance and Settings • Correct Backings and/or Toppings for the Application • Proper Needle Type and Size • Quality Embroidery Threads We will look at each of these elements and discuss potential causes for excessive sewing interruptions. A. INTERRUPTIONS DUE TO NEEDLE THREAD BREAK Digitizing Causes: • Improper cornering with too many stitches in the same location • Not using appropriate underlay stitches that help minimize flagging during the rest of the stitch pattern • Density properties too high within designs that layer many colors of thread • Not using Tie-In Stitches at beginning of thread changes • Not using Short Stitches at the end of a stitching cycle Digitizing Solutions: • Try to minimize the stitch density at any one point. TECHNICAL BULLETIN • Reduce density properties as you build up layers of embroidery • On lettering, use your “short-stitch” function • Use appropriate underlay stitches that help minimize flagging • Use slower speed “Tie-In” Stitches at beginning of thread changes • Use slower speed “Tie-Off” Stitches at the end of a stitching cycle. -

Instruction Manual for Sewing Machine

f2D /3a INSTRUCTION MANUAL FOR I SEWING MACHINE EL3-1© j WHITE’ _____________________________________ WHITE SEWING MACHINE COMPANY Record in space provided below the Serial No. and Model No. of this appliance. The Serial No. is located on Bed Plate. The Model No. is located on Rating Plate. Serial No. Model No. Retain these numbers for future reference. 21&22 CONTENTS Name of Parts 1 & 2 Accessories 3 Before sewing (Power supply and Sewing lamp) 4 Take out extension table, free arm sewing 5 Winding the bobbin 6 Removing bobbin case and bobbin 7 Inserting bobbin into bobbin case 7 Inserting bobbin case into shuttle race 8 Threading upper thread & Twin needle threadg. 9 Drawing up bobbin thread 10 Changing sewing directions 10 Control dial & Adjusting thread tension 11&12 Regulating the presser foot pressure 13 Drop feed 13 Changing needle 14 Fabric. Thread. Needle table 15 Sewing (pattern selector) and operation table 16 To start sewing 17 To finish seam 18 Straight stitch 19 Zigzag sewing 19 Overcasting 20 Stretch stitch 20 Blind stitch Button sewing 23 Binding 23 Zipper sewing 24 Button hole sewing 25 Hemming 26 Twin Needle 27 Embroidery 27 Quilter 28 Seam guide 28 Maintenance (Cle.ning and oiling) 29 Checking Performance Problems WHAT TO DO 30 NAME OF PARTS (FRONT VIEW) 1 Pattern selector dial 8 Sub-spool pins 2 Pressure regulator 9 Top cover 3 Take up lever 10 Zigzag width dial 4 Thread tension dial 1 1 Stitch length dial 5 Presser foot 12 Reverse button 6 Shuttle cover 13 Thread guide for upper 7 Extension table threading —1— (REAR VIEW) Bobbin winder spindle Bobbin winder stopper Upper thread guide Stop Motion knob Hand wheel Face cover Thumb screw Needle plate Presser foot lever —2— ACCESSOR I ES / Bobbin Felt Zigzag foot Button hole (On machine) foot Button foot Machine Oil / Zipper foot 0 Button hole cutter Screw driver Needle #11 #14 —3— BEFORE SEWING 1. -

All About Macramé History of Macramé

August 2019 Newsletter All about Macramé For August we thought we would ring the changes and dedicate this edition of the newsletter to a fibre art that was popular in the 1970’s and 80’s for making wall hangings and potholders but which has recently made a resurgence in fibre art. Some customers have also found that the weaversbazaar cotton and linen warps are ideally suited to macramé. So we have all been having a go. Dianne Miles, one of the weaversbazaar tutors, has extensive experience in Macramé and has designed a one day course to show how the techniques can be incorporated into Tapestry for stunning effect – more details below. So we would like to show you some of the best work going on and introduce you to some of the cross overs with other textile art. History of Macramé The earliest recorded macramé knots appear in decorative carvings of the Babylonians and Assyrians. Macramé was introduced to Europe via Spain during its conquest by the Moors and the word is believed to derive from a 13th century Arabic weavers term meaning fringe as the knots were used to turn excess yarn into decorative edges to finish hand woven fabrics. Probably introduced to England by Queen Mary in the late 17th century it was also practiced by sailors who made decorative objects (such as hammocks, belts etc.) whilst at sea thereby disseminating it even further afield when they sold their work in port. It was also known as McNamara’s Lace. The Victorians loved macramé for “rich trimming” for clothing and household items with a favourite book being “Sylvia’s Book of Macramé Lace” which is still available today.