The Impact of Mother-Son Relationships on the Abandoned Boy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

The Graveyard Book Booklet 202021

King Charles I School Name: Tutor Group: 1 Reading Schedule You must read for at least 30 minutes per day The questions and tasks are optional and are there to extend your understanding of the novel. Week Pages to read 1 1-89 7th September Chapter 1-3 2 90-154 14th September Chapter 4-5 3 155-198 21st September Interlude-Chapter 6 4 199-289 28th September Chapter 7 - 8 2 Context: Author: Neil Gaiman Neil Gaiman was born in Hampshire, UK, and now lives in the United States near Minneapolis. As a child he discovered his love of books, reading, and stories, devouring the works of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien, James Branch Cabell, Edgar Allan Poe, Michael Moorcock, Ursula K. LeGuin, Gene Wolfe, and G.K. Chesterton. A self-described "feral child who was 5 raised in libraries," Gaiman credits librarians with fostering a life-long love of reading: "I wouldn't be who I am without libraries. I was the sort of kid who devoured books, and my happiest times as a boy were when I persuaded my parents to drop me off in the local library on their way to work, and I spent the day there. I discovered that librarians actually want to help you: they taught me about interlibrary loans.” 10 Gaiman's books are genre works that refuse to remain true to their genres. Gothic horror was out of fashion in the early 1990s when Gaiman started work on Coraline (2002). Originally considered too frightening for children, Coraline went on to win the British Science Fiction Award, the Hugo, the Nebula, the Bram Stoker, and the American Elizabeth Burr/Worzalla award. -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

February 2021

F e b r u a r y 2 0 2 1 V o l u m e 1 2 I s s u e 2 BETWEEN THE PAGES Huntsville Public Library Monthly Newsletter Learn a New Language with the Pronunciator App! BY JOSH SABO, IT SERVICES COORDINATOR According to Business Insider, 80% of people fail to keep their New Year’s resolutions by the second week in February. If you are one of the lucky few who make it further, congratulations! However, if you are like most of us who have already lost the battle of self-improvement, do not fret! Learning a new language is an excellent way to fulfill your resolution. The Huntsville Public Library offers free access to a language learning tool called Pronunciator! The app offers courses for over 163 different languages and users can personalize it to fit their needs. There are several different daily lessons, a main course, and learning guides. It's very user-friendly and can be accessed at the library or from home on any device with an internet connection. Here's how: 1) Go to www.myhuntsvillelibrary.com and scroll down to near the bottom of the homepage. Click the Pronunciator link below the Pronunciator icon. 2) Next, you can either register for an account to track your progress or simply click ‘instant access’ to use Pronunciator without saving or tracking your progress. 3) If you want to register an account, enter a valid email address to use as your username. 1219 13th Street Then choose a password. Huntsville, TX 77340 @huntsvillelib (936) 291-5472 4) Now you can access Pronunciator! Monday-Friday Huntsville_Public_Library 10 a.m. -

The Drink Tank 252 the Hugo Award for Best Novel

The Drink Tank 252 The Hugo Award for Best Novel [email protected] Rob Shields (http://robshields.deviantart.com/ This is an issue that James thought of us doing Contents and I have to say that I thought it was a great idea large- Page 2 - Best Novel Winners: The Good, The ly because I had such a good time with the Clarkes is- Bad & The Ugly by Chris Garcia sue. The Hugo for Best Novel is what I’ve always called Page 5 - A Quick Look Back by James Bacon The Main Event. It’s the one that people care about, Page 8 - The Forgotten: 2010 by Chris Garcia though I always tend to look at Best Fanzine as the one Page - 10 Lists and Lists for 2009 by James Bacon I always hold closest to my heart. The Best Novel nomi- Page 13 - Joe Major Ranks the Shortlist nees tend to be where the biggest arguments happen, Page 14 - The 2010 Best Novel Shortlist by James Bacon possibly because Novels are the ones that require the biggest donation of your time to experience. There’s This Year’s Nominees Considered nothing worse than spending hours and hours reading a novel and then have it turn out to be pure crap. The Wake by Robert J. Sawyer flip-side is pretty awesome, when by just giving a bit of Page 16 - Blogging the Hugos: Wake by Paul Kincaid your time, you get an amazing story that moves you Page 17 - reviewed by Russ Allbery and brings you such amazing enjoyment. -

Great Beginnings

GREAT BEGINNINGS Bala Cynwyd and Welsh Valley Middle Schools Suggested Summer Reading 2017 Greetings Parents! Reading is very important to your students’ futures. The higher their level of literacy, the greater the opportunities they will have in education. Please keep your child reading this summer by checking out the summer reading clubs at your local public library or by using the attached suggested summer reading list. The attached summer reading list may help you and your child pick out good books. As librarians, we feel the most important part of our job is matching the right book with the right reader. Since we won’t be able to personally provide this assistance over the summer, we are doing the next best thing. We are providing you with a list of “sure- reads.” These books have such great opening lines that readers will immediately be hooked! Much of this list was compiled from student and teacher suggestions as well as professional journals. Many of the genres are represented. If your child gets hooked on an author, you may want to check out other titles by that same author! The list is alphabetical by author’s last name. Book summaries are provided compliments of the publishers on the Library’s online public access catalog DESTINY. You can find Destiny by going to www.lmsd.org. Select Quick Links, Library Pages, your school, and Destiny in the upper left hand corner. Also available on the District’s web page are the 2018 Reading Olympic titles for middle school readers. Please remember that we have not personally read each book on the list or all of the books by each author. -

The Graveyard Book Neil Gaimon

The Graveyard Book Neil Gaimon The Graveyard Book Neil Gaiman With Illustrations by Dave McKean 2 The Graveyard Book Neil Gaimon Rattle his bones Over the stones It’s only a pauper Who nobody owns TRADITIONAL NURSERY RHYME 3 The Graveyard Book Neil Gaimon Contents Epigraph 1 How Nobody Came to the Graveyard 2 The New Friend 3 The Hounds of God 4 The Witch’s Headstone 5 Danse Macabre Interlude The Convocation 6 Nobody Owens’ School Days 7 Every Man Jack 8 Leavings and Partings Acknowledgments About the Author Other Books by Neil Gaiman Credits Copyright About the Publisher 4 The Graveyard Book Neil Gaimon CHAPTER ONE How Nobody Came to the Graveyard THERE WAS A HAND IN the darkness, and it held a knife. The knife had a handle of polished black bone, and a blade finer and sharper than any razor. If it sliced you, you might not even know you had been cut, not immediately. The knife had done almost everything it was brought to that house to do, and both the blade and the handle were wet. The street door was still open, just a little, where the knife and the man who held it had slipped in, and wisps of nighttime mist slithered and twined into the house through the open door. 5 The Graveyard Book Neil Gaimon The man Jack paused on the landing. With his left hand he pulled a large white handkerchief from the pocket of his black coat, and with it he wiped off the knife and his gloved right hand which had been holding it; then he put the handkerchief away. -

Gaiman's Coraline and the Graveyard Book

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchSpace@UKZN A Critical Analysis of Uncanny Characters in Neil Gaiman’s Coraline and The Graveyard Book by Kamalini Govender Master of Arts in English Studies School of Arts Faculty of Humanities, Development and Social Sciences University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College Supervisor: Dr Jean Rossmann December 2018 CONTENTS Declaration…………………………………………………………………………………... i Acknowledgements…………………………………………………………………………. ii Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………... iii Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… iv Chapter 1 – Literature Review 1.1 On the Author and Novels…………………………………………………………………1 1.2 Critical Scholarship on Coraline…………………………………………………………….. 2 1.3 Critical Scholarship on The Graveyard Book…………………………………………………. 5 Chapter 2 – Methodology and Theoretical Concepts 2.1 The Uncanny……………………………………………………………………………… 7 2.2 The Jungian Shadow……………………………………………………………………… 13 2.3 Liminality, Thresholds and Border Theories……………………………………………… 16 Chapter 3 – An Uncanny Witch: An Analysis of Liza Hempstock in The Graveyard Book 3.1 “They say a witch is buried here.”………………………………………………………….20 3.1.1 An Introduction to Liza Hempstock……………………………………………………...20 3.1.2 “Something girl-like. Something grey-eyed.”: Liza as an Ambivalent Figure……………... 22 3.1.2.1 Liza as a Ghost-Witch-Child……………………………………………………………22 3.1.3. “Got no headstone…Might be anybody. Mightn’t I?”: Liza as an Unhomely Figure……..29 3.1.4 “One of us is too foolish to live, and it is not I.”: -

The Graveyard Book the Graveyard Book

NEIL GAIMAN’s Books for Young Readers NEIL GAIMAN’s THE Graveyard Book Teaching Guide ABOUT THE BOOK When his family is murdered one night by the man Jack, an infant boy toddles unnoticed up the street to the graveyard, where he is taken in and raised by its denizens—ghosts, ghouls, vampires, and werewolves. Such an unusual upbringing affords young Nobody Owens (Bod, for short) almost everything he could wish for, but he still longs for human companionship, news of his family’s murderer, and life beyond the graveyard. Bod’s pursuit of these things increasingly places him in danger, because the man Jack is still looking for him . waiting to finish the job he started. AW A RDS A ND HONORS Newbery Medal Hugo Award Locus Award Boston Globe–Horn Book Award Honor Book ALA Notable Children’s Book ALA Best Book for Young Adults ALA Booklist Editors’ Choice Horn Book Fanfare Kirkus Reviews Best Children’s Book Time Magazine Top Ten Fiction Cooperative Children’s Book Center Choice New York Public Library’s 100 Titles for Reading and Sharing New York Public Library Stuff for the Teen Age Vermont’s Dorothy Canfield Fisher Children’s Book Award Watch Neil Gaiman read The Graveyard Book in its entirety, download The Graveyard Book printable poster, and discover other fantastic delights at www.mousecircus.com. THE GRAVEYARD BOOK TEACHING GUIDE DISCUSSION QUESTIONS 1. From the opening lines, Gaiman hooks readers with a distinct 8. It is often said that it takes a village to raise a child. How does narrative voice and a vivid setting. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1989 Naked Once More by 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show Best Contemporary Novel Elizabeth Peters by Richard Laymon (Formerly Best Novel) 1988 Something Wicked by 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub Carolyn G. Hart 1998 Bag Of Bones by Stephen 2017 Glass Houses by Louise King Penny Best Historical Novel 1997 Children Of The Dusk by 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Janet Berliner Penny 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen 2015 Long Upon The Land by Bowen King Margaret Maron 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates 2014 Truth Be Told by Hank by Catriona McPherson 1994 Dead In the Water by Nancy Philippi Ryan 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. Holder 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank King 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub Philippi Ryan 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1992 Blood Of The Lamb by 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by Bowen Thomas F. Monteleone Louise Penny 2013 A Question of Honor by 1991 Boy’s Life by Robert R. 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret Charles Todd McCammon Maron 2012 Dandy Gilver and an 1990 Mine by Robert R. 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Unsuitable Day for McCammon Penny Murder by Catriona 1989 Carrion Comfort by Dan 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise McPherson Simmons Penny 2011 Naughty in Nice by Rhys 1988 The Silence Of The Lambs by 2008 The Cruelest Month by Bowen Thomas Harris Louise Penny 1987 Misery by Stephen King 2007 A Fatal Grace by Louise Bram Stoker Award 1986 Swan Song by Robert R. -

The Graveyard Book

Reading Group Guide Reading Group Guide Reading Group Books by Neil Gaiman Guide Reading Group Guide A Selected Bibliography Reading Group Guide Reading New! Group Guide Reading Group The Graveyard Book With illustrations by Dave McKean Guide Reading Group Guide Tr 978-0-06-053092-1 • $17.99 ($19.50) Reading Group Guide Reading Lb 978-0-06-053093-8 • $18.89 ($20.89) Reading Group Guide CD 978-0-06-155189-5 • $29.95 ($31.95) Group Guide Reading Group “ The Graveyard Book is endlessly inventive, masterfully told Guide Reading Group Guide and, like Bod himself, too clever to fit into only one place. This is a book for everyone. You will love it to death.” Reading Group Guide Reading —Holly Black, cocreator of The Spiderwick Chronicles Group Guide Reading Group Guide Reading Group Guide Coraline With illustrations by Dave McKean Reading Group Guide Reading Tr 978-0-380-97778-9 • $15.99 ($17.25) Group Guide Reading Group Lb 978-0-06-623744-2 • $17.89 ($22.89) Pb 978-0-380-80734-5 • $6.99 ($7.50) Guide Reading Group Guide Pb Rack 978-0-06-057591-5 • $6.99 ($8.75) Reading Group Guide Reading CD 978-0-06-051048-0 • $22.00 ($26.00) “One of the most frightening books ever written.” Group Guide Group Guide Read- —New York Times Book Review ing Group Guide Reading Group Bram Stoker Award • Hugo Award • ALA Notable Children’s Book • ALA Best Book for Young Adults Guide Reading Group Guide • ALA Popular Paperback for Young Adults • IRA/ CBC Children’s Choice • New York Times Bestseller Reading Group Guide Reading • Amazon.com Editors’ Pick • Book Sense Pick • Bulletin Group Guide Reading Group Blue Ribbon • Child Magazine Best Book • Publishers Weekly Best Book • School Library Journal Best Book Guide Reading Group Guide Coraline Graphic Novel Philippe Matsas Reading Group Guide Reading Adapted and illustrated by P. -

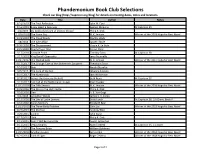

Phandemonium Book Club Selections Check Our Blog ( for Details on Meeting Dates, Times and Locations

Phandemonium Book Club Selections Check our blog (http://capricon.org/blog) for details on meeting dates, times and locations. Date Title Author Notes 3/10/2019 The Final Reflection John M. Ford 2/16/2019 Every Heart a Doorway Seanan McGuire At Capricon 39 1/6/2019 Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Philip K. Dick 11/10/2018 The Stone Sky N. K. Jemisin Winner of the 2018 Hugo for Best Novel 9/23/2018 The Cloud Roads Martha Wells 7/8/2018 The Eyre Affair Jasper Fforde 5/20/2018 The Dispossessed Ursula K. Le Guin 3/25/2018 Ready Player One Ernest Cline 2/17/2018 Cascade Point Timothy Zahn At Capricon 38 1/17/2018 King David's Spaceship Jerry Pournelle 11/11/2017 The Obelisk Gate N. K. Jemisin Winner of the 2017 Hugo for Best Novel 9/17/2017 The Strange Case of the Alchemist's Daughter Theodora Gross 7/16/2017 Binti Nnedi Okorafor 5/7/2017 The Core of the Sun Johanna Sinisalo 3/19/2017 The Humanoids Jack Williamson 2/18/2017 Across the Universe Book #1 Beth Revis At Capricon 37 1/15/2017 Last Call at the Nightshade Lounge Paul Krueger 11/12/2016 The Fifth Season N. K. Jemisin Winner of the 2016 Hugo for Best Novel 9/25/2016 The Man in the High Castle Philip K. Dick 7/10/2016 Slan A. E. Van Gogt 5/1/2016 Leviathan Wakes James S. A. Corey 2/13/2016 The Lies of Locke Lamora Scott Lynch At Capricon 36, 10:00 am, Birch A 1/10/2016 Karen Memory Elizabeth Bear 11/13/2015 The Three-Body Problem Cixin Liu Winner of the 2015 Hugo for Best Novel 9/27/2015 The Martian Andrew Weir 7/26/2015 Lock In John Scalzi 5/17/2015 Ubik Philip K.